Services on Demand

Journal

Article

Indicators

-

Cited by SciELO

Cited by SciELO -

Access statistics

Access statistics

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in

SciELO

Similars in

SciELO -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Investigación y Educación en Enfermería

Print version ISSN 0120-5307

Invest. educ. enferm vol.31 no.2 Medellín May/Aug. 2013

ORIGINAL ARTICLE/ ARTÍCULO ORIGINAL/ ARTIGO ORIGINAL

Nursing care from the perspective of ethics of care and of gender

O cuidado em enfermagem desde as perspectivas da ética do cuidado e do gênero

Cecilia Beatriz Burgos Saelzer1

1 RN, Master candidate. Universidad Austral de Chile, Chile, email: cecilia.burgos@uach.cl.

Receipt date: June 25, 2012. Approval date: February 4, 2013.

Article linked to research: El cuidado en Enfermería desde la perspectiva de la ética del cuidado y género.

Subventions:none.

Conflicts of interest: none.

How to cite this article: Burgos-Saelzer C. Nursing care from the perspective of ethics of care and of gender. Invest Educ Enferm. 2013;31(2): 243-251.

ABSTRACT

Objective. To explore the ethical dimensions of the concept and application of care from a gender perspective, in female and male nurses from a public hospital in the southern zone of Chile. Methodology. Qualitative research was conducted using the case study methodology. Semi-structured interviews were made, between December 2011 and January 2012, of 11 nursing professionals (six women and five men) belonging to Hospital Base in the city of Valdivia, Chile. The data obtained and transcribed were read and coded to establish categories of meaning. Thematic analysis was performed from the statements. Results. A marked service vocation and motivation was observed to apply care, both in men as in women, emphasizing on the psychosocial sphere of patients. Additionally, commitment and application of values were verified in the care giving practice, recognized as part of the excellence of the nursing professional, which they perceive as a characteristic aspect of the profession. Conclusion. Nursing care is not exclusive of the female sex. Males and females develop an ethical sense of care closely linked to the vocational aspects.

Key words: ethics, nursing; nursing care; gender identity.

RESUMO

Objetivo. Explorar as dimensões éticas do conceito e aplicação do cuidado desde uma perspectiva de gênero, em enfermeiras e enfermeiros de um hospital público da zona austral do Chile. Metodologia. Realizou-se uma investigação qualitativa utilizando a metodologia de estudo de caso. Entre os meses de dezembro 2011 e janeiro 2012 se efetuaram entrevistas semiestruturadas a 11 profissionais de enfermagem (6 mulheres e 5 homens) pertencentes ao Hospital Baseie da cidade de Valdivia, Chile. Os dados obtidos e transcritos foram lidos e codificados de maneira de estabelecer categorias de significado. Realizou-se análise temática a partir dos discursos. Resultados. Observou-se uma marcada vocação de serviço e motivação para aplicar o cuidado tanto em homens como mulheres, fazendo ênfases na esfera psicossocial dos pacientes. Adicionalmente, verifica-se que o compromisso e aplicação de valores na prática do cuidado é reconhecido como parte da excelência do profissional de enfermagem. Veem-no como próprio e característico da profissão. Conclusão. O cuidado em Enfermagem não é exclusivo do sexo feminino. Os homens e as mulheres desenvolvem um sentido ético do cuidado muito unido ao vocacional.

Palavras chaves: ética em enfermagem; cuidados de enfermagem; identidade de gênero.

INTRODUCTION

Speaking of nursing brings with it implicitly the concept of care, a theme of vital importance, a pillar of human relations and a society need, which becomes the basis for this profession's development. Considering its beginnings and its relationship with care at the hands of the female gender, and also the evolution it has undergone since the 19th century until now, the question arises of care from a gender perspective and founded on the ethics of healthcare, given that, as concepts, these have been initially linked to nursing, among others reasons, because this profession provides most of the care to the individual and has been directed as a profession, since its beginning, to the female sex. Various nursing theories and models exist that define care as its fundamental axis. Among them, those by Jean Watson and her theory of philosophy and science of care, Katie Eriksson and her theory of charitable care, Madeleine Leininger and her theory of diversity and of the universality of care, Anne Boykin and Savina O. Schoenhofer and nursing as care, among others. Thus, it is how the care giving practice is fundamental for nursing.1 As an emerging science, it seeks to study care within its broader dimension.2 The term care is difficult to define, and even more complex to perceive. According to Royal Spanish Academy, it is defined as the 'application and care to do something well', 'care giving action' (aid, keep, conserve), and 'suspicion, concern, fear'.3

Care granted to the person, from the ethical view, also comprises respect for autonomy, privacy, confidentiality, reliability, and faithfulness.4 The ethics of care, in consequence, claims the importance of understanding and concern for people and their particularities. It also has as central concept the responsibility (from the Latin 'responsum', respond, answer). For Levinás, and from the ethical point of view, it is commitment, being in charge of another and concerned for what occurs to another.5 For this author, responsibility is not conditioned to any knowledge; in fact, it occurs upon meeting face-to-face with the other. The ethics of responsibility obligates us to be responsible for the other individual, even before meeting that person.6 From Kantian ethics, humanity itself is a dignity because man cannot be treated by any man (nor by another, or by oneself) as a simple means or instrument, but always as an end in itself, and, therein lies precisely humanity's dignity.7 An end that has no price and which, hence, cannot be substituted by any equivalent, conferring to dignity a criterion of moral application.8 The responsibility is made evident upon the frailty and vulnerability, and the response is care giving, as a form of solidarity responsibility, as an exercise of justice before the world, under the view of global bioethics.

From the gender vantage point, its construction is formed through a process taking place subjectively among individuals and objectively it is experienced by the world. It is a social construction influenced by political, economic, and cultural systems that throughout history have stereotyped men and women as two symbolic universes, totally different in everything concerning their internal dynamics and how they extrapolate these dynamics to bring them to the daily plane. Women would be characterized by the responsibility, the rationality with which they face situations and their solution capacity. Instead, men socialize under a vision that would include different dimensions, but not necessarily pertinent to the male gender, such as technology, economy, and burocracy.9

During previous times, caring was - and in many places continues being - a task relegated to women, without being assigned much importance, but currently it is an important indicator of the quality of health services.

The Florence Nightingale reform marked a peak period for feminization of nursing, given that in 1867 she proposed in one of her letters that: 'The reform consists in taking the power from the hands of men and placing it on the hands of trained women to make them responsible for everything concerning nursing'.10 With this, she installed the concept that this profession was inherent to women, acting as the executor of the household activities and the nursing exercise within the family, during a period in which life was under a patriarchal model, where the man was the father and head of the family. If extrapolated to the institutional model, it may be observed that nurses work under physician's orders, who would be assuming the father role. Hence, the notion of the male nurse was incompatible with the institutional model.11

The male model, of impartial justice, would correspond to physicians (curing); the female model, of attention and care, would correspond to female nurses (caring). Care, as solicitous and altruist caring for another requiring help, is inalienable, but its exercise must be carried out within the framework of justice.12 Compassion and care must be complemented with the universal principles of justice, thus, reaching maturity of moral development. Regarding the evolution of human development, according to Kohlberg, moral maturity would be reached by stages, agreeing with research that proposed moral dilemmas to children (males) of different ages, to evaluate responses and determine if common patterns existed that permit establishing a sequence of phases.13 Her disciple, Carol Gilligan, questions the aforementioned due to gender bias for having investigated only with males. She proposes after an investigation (including children from both sexes) that all reach moral maturity, but in different stages and times.14 She poses the hypothesis that moral intuitions would be unconscious, involuntary, instinctive, as a sort of 'innate moral sense', which would be independently present in Nursing care from the perspective of ethics of care and of gender human beings and which would predominate over intellectual learning. Additionally, she proposes that males would present an ethical orientation to justice and rights, while women would present an ethical orientation to care and responsibility.15 According to the aforementioned, it is valid to ask: What do nursing professionals understand for care? Care as an ethical concept is understood and applied same way by female and male nurses? Are males also able to care?

METHODOLOGY

The study opted for qualitative research to have flexibility in the search of understanding the phenomenon, with respect to unpredictable factors during the development of the study. This methodology appears as a perspective to view social phenomena, among them those of health and disease. This work is described as a descriptive exploratory study adopting the case study as tradition.16,17 This approach has been considered useful as a creative alternative to traditional description approaches, emphasizing on the perspective of individuals as the center of the process. This tradition was selected given interest in examining and in-depth exploring the perception of clinical female and male nurses in relation to the concept of care from an ethical and gender point of view.

Through a theoretical sampling, 11 nursing professionals from both sexes were intentionally selected - six female nurses and five male nurses - belonging to Hospital Base from the city of Valdivia, Chile, between December 2011 and January 2012. The maximum variation sampling methodology was followed.18 This strategy permitted representing diverse cases to show multiple perspectives on the study case and, thus, document the whole variation of the phenomenon to discern common patterns and ranges of variation and differentiation. Consequently, female and male nurses of different ages, years of professional exercise, and clinical services were incorporated. The number of participants was determined by the saturation criterion.

In keeping with the purposes of the study, the semistructured survey was used as the technique to collect the data. The purpose of the survey conducted as part of a case study is to discover what occurs, why, and what it means; in turn, we expect to generalize broader processes, discover causes, and explain or understand a phenomenon.19 Through them we gained access to contents of meaning and it was the only event occurring between the respondent and the interviewer in isolated and formal manner. The survey also had a series of introductory questions, which served as a guide for the survey. In turn, the following topics or dimensions were anticipated according to which the guide questions were structured: professional experience and trajectory when offering care, concept of care, application of care, evaluation of care. Nevertheless, survey development maintained its flexible character and permitted free expression from respondents.

From the ethical point of view, the study protocol was evaluated by the Ethical-Scientific Committee of the Valdivia Healthcare Service. This research secured consent from the respondents to obtain and use the data, as well as authorization to register the surveys and for the respondents' freedom of electing to participate or withdraw from the study, respecting their autonomy and confidentially evaluating the information gathered. Consequently, respondent participation and the surveys in particular had a formal character, focused on topics or specific themes and were planned and programmed with the nursing personnel at the moment of developing the informed consent process. Information and data were stored as field notes, digital sound recording (WAV format), transcriptions and text computer files (MS Word). For data analysis the information was grouped according to preestablished dimensions, developing categories and subcategories, seeking to closely rescue the essence of the discourse through the interpretation and recurrence of the statements in the recorded surveys. Once a survey was conducted, it was faithfully transcribed in detail according to that expressed by the respondents; then, it was analyzed via content analysis. Through repeated readings, common themes and differences were verified and registered. Thus, the data obtained and transcribed were read and coded to establish categories of meaning. To safeguard the identity of the participants, the different testimonies were described by using the survey's sequential number according to its occurrence (E1 - E11).

RESULTS

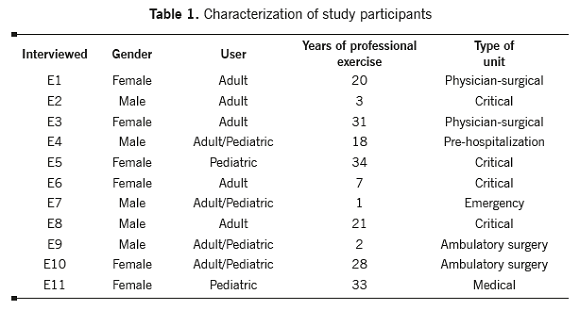

The participants were characterized for representing both genders, with an average of 18 years of professional exercise, both in pediatric and adult care (Table 1). The group of interviewees most worked in clinical services of closed care and only 36% in ambulatory care.

The results are described from the four dimensions established for their analysis. Among them, the research's most relevant sub-categories were exposed along with some textual quotes delivered by the interviewees, showing the predominant perceptions among the professional male nurses from Hospital Base Valdivia.

Dimension 1. Professional experience and trajectory when offering care

Upon analyzing the category of experience acquired over time when providing care, the interviewees, with an average of 25.5 years of service for women and nine years for men, indicate that it has been gratifying -as the most recurrent adjective-: (.) Gratifying, down deep it is an experience that when you think about it, it is what I wanted and the important thing is the attachment relationship you accomplish with patients and trying to solve their problems. (E1); (.) God has filled me with gifts (.) of fondness. I am in a place I like; I do what I enjoy. (E5); (.) Gratifying to be able to help another individual. (E7).

The balance has been positive throughout the years, highlighting the vocation and degree of commitment and empowerment of professionals in their roles. We observed high motivation in professionals from different services, with declarations like: (.) Since when I was a student I fell in love with nursing, I am very fond of the work I do . (E6); (.) Good, my experience has been good; I think that as a nurse if I had to study, I'd study nursing again. (E11). Nonetheless, differences are described in relationship to types of patients. In this sense, in critical units the relationship with patients with altered conscience does not permit close contact, instead the execution of specific techniques or punctual care is emphasized: (.) There are patients with no type of verbal contact, because their conscience is altered, so in these types of patients we merely perform procedures and care, control and evaluation. (E4). For males, a motivation is the overvaluation perceived and which permits reasserting themselves in their performance: (.) I can solve situations and perform care. (E9).

Also mentioned is the holistic manner of approaching care, highlighting direct contact with patients and their families. Although differences are not described among patients attending public and private care, the interaction with their family members is different. Additionally, differences are noted in providing care and in the relationship with ambulatory and hospitalized patients: (.) It is not merely patients lying in bed; rather, you see them in holistic manner, their family, their environment, everything. (E3); (.) The satisfaction of delivering care is equal in the public and private spheres. Patients are generally the same, but the families are different. (E3); (.) Given that this is an emergency service, it is not a continuous contact with the patients, nor as prolonged as it could be in a hospitalization service, where one often comes into closer contact with patients. (E7); (.) You have patients who remain up to 14 or 15 days with you, hence, establishing better links. (E8).

Dimension 2. Concept of care

Analysis of the interviewees' concept of care results interesting, given that without gender distinction they coincide in important aspects, like satisfying basic human needs, helping another, providing tools for health recovery and reincorporation to their environment: (.) Satisfying basic human needs of those who cannot satisfy them on their own. (E2); (.) It is the necessity patients have of receiving care according to their ailment, not to what I want to give. (E4); (.) Care is helping another, being there when someone has a need they cannot satisfy on their own. (E6); (.) It is supporting and accompanying that person throughout that process. (E7); (.) It is providing comprehensive care to those who need it. (E8); (.) Teaching when others do not know; helping when there is partial disability; or supplementing when there is total disability to satisfy basic needs. Maintaining health and wellbeing of the whole person, because that sometimes includes areas that are not as physical. (E9); (.) Care is fondness, respect, mysticism. you are born with that; if not you must learn it. (E5).

Dimension 3. Application of care

The category of how to apply care mentions concepts like support, listening, holistic, commitment, mysticism, respect, fondness, and act of continuous and transversal service: (.) It is present from the time you are born and until you are dying. (E10). Again, the family is included at the moment of providing care, given that currently companionship is accepted and promoted during hospitalization: (.) Providing support, listening many times, and trying to intercede for the patient (.) also integrating the family (.) previously, hospitalizations were more prolonged, you did everything for the patient, now people want to be discharged sooner and the family is integrated. (E1); (.) Meeting the mother, the family (.) if they will be present to help us in caring for the child. (E11); (.) in holistic manner. You are not perceiving the patient as a thing in the bed, a thing from which you and the rest of the team will learn, but as a commitment, (.) you, as a person, must have special human characteristics to provide care, (.) we are instruments of God and mysticism is quite linked to accompanying the patient. (E5); (.) Care appertains to nursing, I believe we are the professionals who have a wider vision regarding the patient's needs and we do not focus on specific issues like other professionals. (E6); (.) Trying to avoid doing things on the technical part. sometimes not even talking, sometimes it is a matter of only listening. (E7).

Although they highlight that care should encompass all areas, biological and psychological, they recognize that much of the latter is left aside when dealing with unconscious patients or due to care giving pressure, limiting themselves more to biological care: (.) Regrettably, where I work patients are all unconscious, then, we satisfy biological necessities more than anything else (.) we could say care giving is partial. (E2).

In the statements by male nurses who have experience in pre-hospitalization units, care giving is described as more structured and rational, focused on the application of protocols:(.) A bit evaluating the patient's condition (.) if intervention is needed and at what level. Only education, only support or completely or in sets supplementing several issues (.) and also adapting according to conditions and resources. (E9); (.) We base ourselves on protocols and treatment standards. (E4).

Dimension 4. Evaluation of care

Upon analyzing the evaluation performed on nursing care, we must differentiate two subcategories, the perception of the patients and that of the healthcare team (physicians, nursing personnel, and paramedical technicians). The terms trust and commitment appear in different surveys to highlight the importance granted to providing care. The perception by physicians is positive, recognizing and trusting the actions by nursing, which aim to treat problems mainly from the biological sphere: (.) There is good reception within the medical team, you are somewhat important for them. (E1); (.) Biological care is evaluated quite well [in the opinion of physicians], but emotional or psychological care is not considered much. (E2); (.) Physicians trust my work. (E8). Rather, collaboration personnel assign the greatest importance to medical indications: (.) Care has been evaluated well by the team, by patients, and by the personnel (.) because they feel more empowered of the care provided; it is not the same to assign six to eight patients than three. (E3); (.) But technicians do not see it as important, they only perceive medical indications as important. (E1).

Recognition from patients is almost always perceived as positive, stressing the importance of empathy: (.) If you go and explain to the patient what you are doing or speak a while with the patient and show a little empathy, they will appreciate that a lot. (E2); (.) within the nursing group, I would say that we are all committed and enthusiastic. (E6); (.) Very few family members complain. and most complaints are related to cold and impersonal treatment. (E6); (.) The team respects the fact that one has a human side more than a technical side. more complete treatment of the person. (E7); (.) My patients appreciate this well (.) they trust me and the team (...) because they come back, even with problems of another nature. (E1).

DISCUSSION

Ethics in the nursing profession has undergone big changes in recent decades. The profession has gone from ethical care based on a way of being, centered on the virtue of obedience, submission, and adhesion to a pre-established code of conduct, to developing ethics based on respect, scientific and professional rigor, and human rights. This study permitted gathering the perspective of nursing professionals from different clinical services, evidencing that no substantial differences exist in the description of the concept and exercise of care linked to gender. Additionally, it was verified that commitment and application of values in care giving are recognized as part of the excellence of nursing professionals; they perceive it as appertaining and characteristic of the profession. Analysis of the declarations obtained of how female and male nurses experience, understand, apply, and self reaffirm themselves with the evaluation of care giving, point to the same goal: preserving the dignity of human beings. We are aware of the vulnerability of nature, of others and of ourselves; we see our own frailty in the frailty of others, we empathize.

The adjective gratifying was the most used by both genders to define the degree of satisfaction upon providing care, which grants an ethical value to the motivation to perform their professional and Nursing care from the perspective of ethics of care and of gender care giving role, in spite of the long work shifts and beyond the exclusive search for economic rewards. Ethics belongs in care giving and it is from ethics that the principles governing the profession are developed. Due to that, care is an ethical reference as are principles and human rights.20

Men and women socialize under different behavior guidelines, indicating different gender patterns: women are characterized by the responsibility and rationality with which they face situations and their solving capacity. It is also attributed that the difference in ethical behaviors between men and women could be the result of education and, even, of a discriminatory situation in which women have always been relegated to functions of service and attention to the household needs. The professional environment is one of the fields that perhaps fosters greater gender confrontation and reveals the potentialities and weaknesses of both, a situation that is often conflictive and carries total divergence between the sexes, but leads to wondering on the success that can be accomplished by using the complementarity. Being a minority group offers males the opportunity to perceive themselves positively and as a facilitating challenge toward practicing the profession as a consequence of the desire to show that men, like women, can provide care.21 This has already been demonstrated in the stages of professional formation, as proposed by Whittock and Laurence, who through comparative surveys between student male and female nurses of different ages and ethnicities, found that men are seen as dedicated to care as women are.22

It is interesting that the responses from male nurses are more rational and structured when speaking of how they apply care, demonstrating a clear inclination to responsibility, which responds, on the one hand, to a conventional level of moral development and, on the other hand, to a central concept of the ethics of care.15 According to Stott, male nursing students feel more comfortable performing in high-pressure technological areas, assuming it as a challenge. This, from a gender perspective, could be understood as the product of the pleasure experienced by men when working with technology, besides the reflection of male characteristics like taking on challenges and risk.21

However, we cannot speak of different ethics or of ethics for men and ethics for women. The ethical behavior of all human beings implies the relationship of many elements. In that sense, the ethics of care cannot be ethics only 'for women', but which corresponds to the most profound exigencies of the whole person, called to exist from the rest and for the rest. Development of the gender concept does not seek to re-elaborate already existing terms focused on man and woman; rather, it helps to reframe highly important issues for both and find responses that lead to better understanding the relationship that exists among existing conceptions to that respect and how these influence in the application of care. When considering nursing care as a complex and multifaceted phenomenon, the challenge is to understand it in its multiple expressions. Only, thus, will male nurses have a solid base for care that recognizes its value, social and political dimension, and implication in the lives of citizens.23

Finally, the ethics of care has positive characteristics that only human beings with spirit of service can grant. Additionally, it does not distinguish gender, ideology, or race, which makes care a call to serve.

REFERENCES

1. Marriner A, Raile M. Modelos y teorías en Enfermería. Sexta ed. Barcelona: Elsevier; 2007. [ Links ]

2. Hernández A, Guardado C. La Enfermería como disciplina profesional holísitica. Rev Cubana Enfermer. 2004; 20:1-1. [ Links ]

3. Real Academia Española. Diccionario de la lengua española. 22nd ed. Madrid: Espasa Calpe; 2001. [ Links ]

4. Garzón N. Etica profesional y teorías de Enfermería. Aquichán. 2005; 5:64-71. [ Links ]

5. Romero E, Gutierrez M. La idea de responsabilidad en Levinàs: implicancias educativas. In: XII Congreso Internacional de teoría de la educación. Barcelona: Universitat de Barcelona; 2011. p.1-12. [ Links ]

6. Tangyin K. Reading Levinas on Ethical Responsibility. In: Kwan T, editor. Responsibility and Commitment. Eighteen Essays in Honor of Gerhold K. Becker.Waldkirch: Edition Gorz; 2008. [ Links ]

7. Jiménez JL. La dignidad de la persona humana. Bioética. 2006; 6:18-21. [ Links ]

8. Pose C. Bioética de la responsabilidad. 1st ed. Madrid: Editorial Triacastela; 2012. [ Links ]

9. Nilsson K, Larsson US. Conceptions of gender--a study of female and male head nurses' statements. J Nurs Manag. 2005; 13:179-186. [ Links ]

10. O'Lynn C. History of men in nursing: A review. In: O'Lynn C, Tranbarger R, editors. Men in nursing: history, challenges, and opportunities. New York: Springer Publishing Company; 2006. [ Links ]

11. Evans J. Men nurses: a historical and feminist perspective. J Adv Nurs. 2004; 47(3):321-8. [ Links ]

12. Feito L. Aspectos filosóficos de la relación entre las mujeres y la bioética: hacia una perspectiva global. In: De la Torre FJ, Editor. Mujer, mujeres y bioética. Madrid: Universidad Pontificia Comillas; 2010. [ Links ]

13. Kohlberg L. Psicología del desarrollo moral. Bilbao: Descleé de Brouwer; 1992. [ Links ]

14. Gilligan C. In a different voice: psychological theory in wowen's development. United States of America: Harvard University Press; 1993. [ Links ]

15. Gilligan C. La moral y la teoría. Psicología del desarrollo femenino. México: FCE; 1985. [ Links ]

16. Yin RK. Case Study Research: Design and Methods. Thousand Oaks, CA.: SAGE Publications; 2003. [ Links ]

17. Stake R.E. Case studies. In: Denzin K, Lincoln S, editors. Handbook of qualitative research. 2nd ed. Thousand Oaks, CA.: SAGE Publications; 2000. [ Links ]

18. Creswell JW. Qualitative Inquiry and Research Design: Choosing among Five Traditions. 2nd ed. London: SAGE Publications; 1998. [ Links ]

19. Rubin HJ, Rubin IS. Qualitative Interviewing. The Art of Hearing Data. 2nd. California: SAGE Publications; 2004. [ Links ]

20. Busquets M. La ética del cuidar. In: V Congreso Nacional de Enfermería en Ostomías. Pamplona: Sociedad Española de Estomaterapia; 2004. p. 27-34. [ Links ]

21. Stott A. Exploring factors affecting attrition of male students from an undergraduate nursing course: a qualitative study. Nurse Educ Today. 2007; 27(4):325-32. [ Links ]

22. Whittock M, Leonard L. Stepping outside the stereotype. A pilot study of the motivations and experiences of males in the nursing profession. J Nurs Manag. 2003;11(4):242-9. [ Links ]

23. de Souza M, de Bona VV, Coelho de Souza MI, do Prado ML. O Cuidado em Enfermagem: uma aproximação teórica. Texto Contexto Enferm. 2012; 14(2):266-70. [ Links ]

text in

text in