Services on Demand

Journal

Article

Indicators

-

Cited by SciELO

Cited by SciELO -

Access statistics

Access statistics

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in

SciELO

Similars in

SciELO -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Colombian Applied Linguistics Journal

Print version ISSN 0123-4641

Colomb. Appl. Linguist. J. vol.13 no.2 Bogotá July/Dec. 2011

The motivational properties of emotions in Foreign Language Learning

Las propiedades motivacionales de las emociones en el aprendizaje de una lengua extranjera

Professor at Departament of Language and Education

Universidad de Quintana Roo

Chetumal, Quintana Roo; México

E-mail: marizam@uqroo.mx

*Realizó estudios de Licenciatura en Lengua Inglesa en la Universidad Veracruzana, Maestría en Psicopedagogía en la Universidad de la habana, Maestría en TESoL por la Universidad de Manchester, Inglaterra, Doctora en Educación por la Universidad de Nottingham, Inglaterra. Especialidad: variables afectivas en el aprendizaje del inglés, estrategias de aprendizaje.

Received: 13-Sept-11/ Accepted: 20-Nov.-11

Abstract

Although the process of learning a foreign language is replete with emotions, these have not been sufficiently studied in the field of English Language Teaching. The aim of this article is to report the motivational impact of the emotions experienced by second year students of an English Language Teaching programme in a South East Mexican University. Students were asked to keep an emotional journal for twelve weeks during their third term in order to map their emotions and their sources during instructed language learning. The results show that the emotions experienced most by students are: fear, happiness, worry, calm, sadness and excitement. Although there is a range of sources for emotional reactions, the five main sources of students' emotions are: their insecurity about their speaking ability, the teachers' attitudes, comparisons with peers, the classroom atmosphere, and the type of learning activities.The two main aspects identified as impacting on students' motivation are: the teachers' attitudes, and the classroom climate.

Key words: affect, emotions, language learning, motivation.

Resumen

Aunque el proceso de aprendizaje de una lengua extranjera está lleno de emociones, estas no han sido suficientemente estudiadas en el campo de la enseñanza del inglés. El propósito de este artículo es reportar el impacto motivacional de las emociones experimentadas por estudiantes de segundo año de la licenciatura en Lengua Inglesa en una universidad del sureste Mexicano. Los estudiantes plasmaron en un diario las diversas emociones experimentadas así como sus reacciones durante doce semanas en el tercer semestre de su carrera con el propósito de mapear sus emociones y las fuentes de éstas durante la instrucción en el aula. Los resultados muestran que las emociones más recurrentes durante la instrucción son: miedo, alegría, preocupación, tranquilidad, tristeza y entusiasmo. A pesar de que hay diversas fuentes que originan estas emociones, los cinco orígenes principales de éstas son: la inseguridad al hablar en inglés, las actitudes de los profesores, la comparación con sus compañeros, el ambiente en el salón de clases y el tipo de actividades de aprendizaje. Los dos aspectos identificados como los que influyen más en la motivación de los estudiantes son: las actitudes de los profesores y el ambiente de aprendizaje.

Palabras claves: afectividad, emociones, aprendizaje de lenguas, motivación.

Introduction

Although affect has been recognised as having a crucial role in foreign language learning (Ellis, 1994; Arnold and Brown, 1999), the investigation of emotions has not been at the forefront of the research agenda in the English Language Teachingfield (Dewaele, 2005; Garret and Young, 2009). Cognition has been emphasised in English Language Teaching research in spite of the interplay that both dimensions have on learning (Arnold, 1999). However, there are numerous scholars who have acknowledged that foreign language learning motivation is emotionally driven (MacIntyre, 2002; Dörnyei, 2005; Aki, 2006; Garret and Young, 2009; Bown and White,2010; Imai, 2010). Attention to emotions engendered in language learningcan help overcome problems of demotivation created by fear or anger which can risk foreign language learners' potential. In addition, trying to evoke emotions that enhance learners' self-esteem and promote empathy can contribute to reenergising students' motivational energy and facilitating language learning.

Emotions in learning

In the field of psychology, integral components of affect are emotions, feelings and moods (Forgas, 2001). In education literature, emotions and feelings are included interchangeably and are considered close in meaning (Scherer, 2005). The close interrelationship between emotions and feelings makes it very difficult to separate the two concepts. However, moods seem to be more likely to be distinguished from emotions since the latter can be traced as reactions to particular events, whereas mood changes sometimes may not be attributable to a specific reason, have a longer effect and are very ambiguous (Ekman, 2003; Do and Schallert, 2004; Scherer, 2005). Emotions in educational contexts are said to be context-dependent, short-lived and subjective responses to a specific situation, object or person (Do and Schallert, 2004; Sansone and Thoman, 2005; Hascher, 2008).

Foreign language learners are prone to experience a range of emotions and feelings during this complex processdue to internal and external factors. It is important to pay attention to feelings and emotions originated during foreign language learning instruction since 'When we educators fail to appreciate the importance of students' emotions, we fail to appreciate a critical force in students' learning (Immordino-Yang and Damasio, 2007, p. 9). The diverse emotions that students may experience during learning activities can cause different affective reactions in students. Difficult situations have been classified by Fridja (1988) as 'annoyers' because students consider that these events may cause damage, loss or harm. Besides, if students perceive that a task is difficult but experience feelings of joy, relief or pride while doing it, they tend to adjust their perceptions and become willing to try new activities in the future. Thus the emotions involved in this appraisal process provide students with the motivational energy to direct their actions and modulate their thinking. This process of appraisal is a critical part of any learning process since it is going to determine its continuity or ending.

Emotions regulate changes and adjustments students go through at university. The result of this developmental process may be positive or negative and its result depends on the ability students have to organise these changes into a positive psychosocial identity (Erickson, 1968). The formation of a positive identity is a task that should be supported not only by parents but also by teachers. Supporting students' emotions in language learning classrooms can help students to cope with feelings inherent to language learning experiences and to the development of a positive attitude towards themselves as language learners. As stated by Garret and Young (2009) "It is through experiencing the world and conducting an affective appraisal of these experiences that individuals develop their own unique preferences and aversions" (p. 210).Thus, understanding the emotions experienced by language learners and their impact on their academic performance may help language teachers to help students manage these emotions to their advantage.

Emotions and language learning motivation

Although the process of learning a foreign language is replete with emotions, these have not been sufficiently studied in the field of English Language Teaching. If we were to ask a foreign language learner to list the different emotions she or he had gone through during the learning process, I believe the list would be a long one. Yet, as MacIntyre (2002) states, "Emotion has not been given sufficient attention in the language learning literature, with the exception of studies of language anxiety" (p. 45).

The one factor that has been considered to determine success or failure in second and foreign language learning is motivation (Dörnyei, 2001). Although originally motivation was considered more a cognitive variable than an affective one, the impact of emotions on motivation is starting to gain ground in the ELT field. MacIntyre (2002) highlighted that "...the motivational properties of emotion have been severely underestimated in the language learning literature" (p. 61). Along the same lines, Dewaele (2005) calls for more research focus on affect and emotion in order to pay increased attention to the communication of emotion and the development of sociocultural competence in a second language. Schumann's (1998) neurobiology theory considers feelings and emotions as crucial to the understanding of second language achievement. According to him, learning a second or foreign language is manipulated by our emotions, and emotions shape behaviour and perhaps all cognition. Brain research emphasises theclose connection between emotions and cognition (Jensen, 2005). Immordino-Yang and Damasio (2007) highlighted that "The more educators come to understandthe nature of the relationship between emotion andcognition, the better they may be able to leverage this relationshipin the design of learning environments" (p. 9).The effect of learners' emotions on their motivation appears to be a line to follow in future language learning motivation studies. As MacIntyre (2002) suggests, "... emotion just might be the fundamental basis of motivation, one deserving far greater attention in the language learning domain" (p. 45).

It is widely recognised that the school environment originates diverse emotional experiences in students which are a powerful influence on students' interest, engagement and motivation(Efklides and Volet, 2005; Gläser-Zikuda and Järvelä, 2008; Schutz and DeCuir, 2002). The feelings and emotions engendered in educational contexts are said to be a result of the evaluation students make of particular situations while learning (Pekrun, 2000). These evaluations are influenced by previous experiences, the social context, and their personal goals (Pekrun et al., 2002; Sansone and Thoman, 2005). This is of particular relevance to the learning of a foreign language since most of the time students come with previous positive or negative experiences; sometimes the learning environment may be very different from previous ones, and they may have very different motives for engaging in foreign language learning.

Although affect has always been a pervasive component of motivation, it has been eclipsed in motivation research because of the interest in cognition (Meyer and Turner, 2006). Motivational psychology theories such as self-efficacy theory (Bandura, 1997), attribution theory (Weiner, 1992), self-worth theory (Covington, 1998) and self-determination theory (Deci and Ryan, 1985) conceive affectivity as the core of motivation behaviour. Learners' behaviour is determined by the need to protect their self-image and to preserve their self-worth, and is influenced by significant others and the socio-cultural context in which they live. Thus, motivation is powerfully influenced not only by learners' personalities but also by personal experiences, cognitive processes and the social context. All of these imply an array of emotions and feelings aroused in intra- and interpersonal interactions. A complex interaction of numerous student and situational characteristics determines foreign language learners' motivation. Given that language learning is a socially constructed process, the diversity of emotions experienced is a crucial aspect impacting on the motivational behaviour displayed by foreign language learners.

The powerful force our emotions play in language learning motivation is reflected in early motivational studies, in which positive feelings towards the target language community (integrative orientation) or the instrumentality of language (instrumental orientation) were seen as strong determinants of success (Gardner and Lambert, 1972).Due to the complexity of the motivation construct it has been difficult to reach a comprehensive theory (Dörnyei, 2001). Different motivational approaches have been developed in order to try to come up with a better understanding of the concept.The lack of applicability of the outcomes of research on motivation in the past decades led Dörnyei(2001) to develop a framework of motivational strategies for teachers to use in order to develop learners' intrinsic motivation. According to Dörnyei(2001), 'Motivational strategies cannot be employed successfully in a 'motivation vacuum' – certain preconditions must be in place before any further attempts to generate motivation can be effective' (p. 31). These three conditions are: appropriate teacher behaviours and a good relationship with the students; a pleasant and supportive classroom atmosphere; and a cohesive learner group with appropriate group norms. Humanistic education acknowledges the importance of making students feel valued, encourages cooperation among learners and emphasises the importance of creating a non-threatening environment in which learning is facilitated. We can find these principles embedded in the conditions Dörnyei(2001) considers to be the core attributes for the development of intrinsic motivation in language learners.

An influential theory developed in mainstream psychology which has influenced English Language Teaching is that of Deci and Ryan (1985), which distinguishes between extrinsic and intrinsic motivation. Under this distinction, learners who are extrinsically motivated (by obtaining rewards such as grades or prizes) depend on their performance, since this will regulate those external rewards that make their motivation increase or decrease. Conversely, learners who are intrinsically motivated (learning because the task gives the learner a sense of identity and pleasure) can regulate their behaviour and attitudes towards the language learning situation in general. Due to its external component, which is not regulated by the learner but by some other agent, extrinsic motivation is considered not to be favourable for language learning, whereas intrinsic motivation is considered the most reliable type of motivation that makes learners successful because of its total dependence on the self.

A recent proposal in learning motivational studies is Dörnyei's (2005, 2009) theory of the motivational self-system, in which the two main constructs – the Ideal L2 Self and the Ought-to L2 Self – imply the emotional baggage of motivation in language learning, since an Ideal L2 Self is a pressure on a learner's learning process and can produce negative effects on students who see that their Ideal L2 Self is very far from their real one. Hence, there is a paramount need to deepen our understanding of emotions in foreign language learning, for as Dewaele (2005) stated:

A focus on affect and emotion among researchers might inspire authors of teaching materials and foreign language teachers to pay increased attention to the communication of emotion and the development of sociocultural competence in a L2. (p. 367)

This article reports on a qualitative study carried out to identify the emotions experienced by 18 Mexican language learners, the sources of these emotions and how these influenced their motivational behaviour in classrooms.

Methodology

In order to be able to understand how emotions originate and then develop during a language learning process, it was necessary to explore students' experiences, to give a detailed account of their views, and to describe the context in which these emotions are being experienced. Qualitative methods allow us to gain a deep understanding of the motives behind human behaviour (Barbour, 2008). Thus, a qualitative study was designed since this approach was suitable to the purpose of this research. Although presenting the 'real' truth is something that I consider we cannot fully accomplish, because we are all actors in the society in which we live and interact, I do believe that qualitative methods can help us better understand a phenomenon in a given community or setting. The journals analysed in this article are one of three instruments used in a wider qualitative study. This article only reports on the data drawn out from learners' emotional journals. The following research questions were formulated:

- Which emotions do students of a foreign language experience over a term?

- In which situations or events in instructed foreign language learning do theseemotions originate?

Setting and participants

This study was carried out at a South East Mexican University. A group of 24 students in the third term of the ELT programme was invited to take part in the project. Only 20 (13 female and seven male) students agreed to participate, and voluntarily kept a structured journal for 12 weeks during their second year in the programme. Students at this institution are from both rural and urban backgrounds.

Data collection method

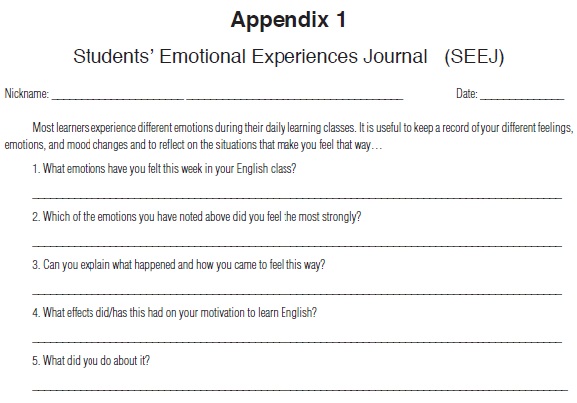

This article reports on the data collected through an electronic journal. Students were given an electronic format to capture their emotions and their sources for a period of 12 weeks (see Appendix 1). Students were advised to write as many journal entries as desired per week in order to keep a map of their emotional experiences. Students were not limited in terms of the type (negative or positive) of emotion to report, or in the number of journal entries to write per week. Every Friday students were responsible for sending their journal entries by e-mail to the researcher.

Students Emotional Experiences Journal (SEEJ)

In the journal entries, students became observers of their own emotional experiences and were asked to record these as honestly as possible. Some entries included introspective reflections on their own experience (Bailey, 1983). In this study, the journals were focused on those emotional moments students experienced during classroom instruction that triggered in them an emotional reaction. Journals have been found to be:

Like a checkpoint between your emotions and the world. They are private but allow you to view your feelings from some distance. In a journal you can clarify, release, organize and soothe your feelings. You can experiment without consequences. Journals provide flexibility for approaching and understanding your own emotions. (Jacobs, 2004 p. 3)

According to Hascher (2008), journals about emotions in educational settings should not be 'weighted' but contextualised, since emotions originate due to specific situations. Thus, students were asked not only to report on the emotions experienced, but also to describe why and how that emotion originated. Students were free to report about any emotion felt. They were not restricted to a set of specific emotions since, by limiting students to concentrating on specific emotions, emotional experiences that the students considered important could be missed. This is one of the common limitations of studies on emotions in education (Pekrun et al., 2002).

Students described the situations that originated an emotional reaction, how they felt during that event, why they felt in that way, and what their reaction to it was. Students handed in their journals entries every week and were asked to focus on those emotional moments they considered to have had a strong impact on them. Thus, it was expected that the journal would allow them to reflect not only on the situation and their reaction to it, but also to analyse if that event had any impact on their language learning process. Journal writing allowed students to reflect on why some changes may have been happening to their language learning energy, and to assess whether emotions originating in classroom instruction were affecting it.

Data analysis

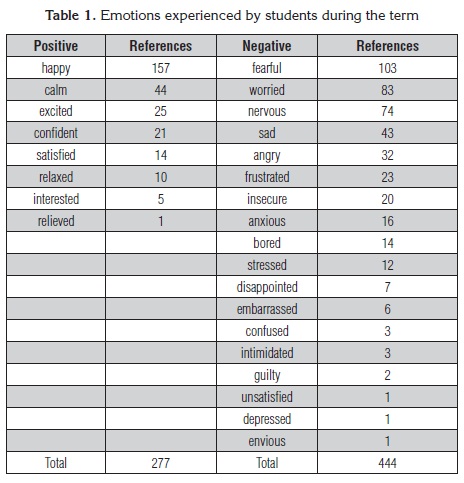

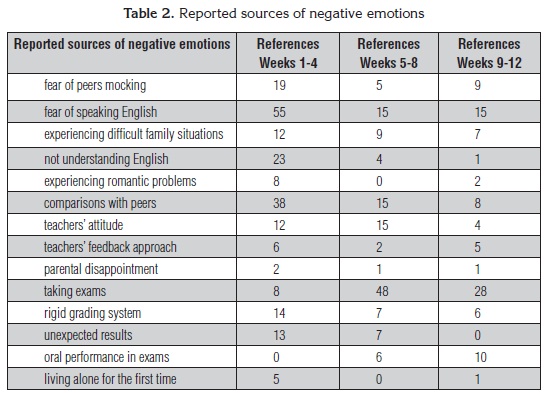

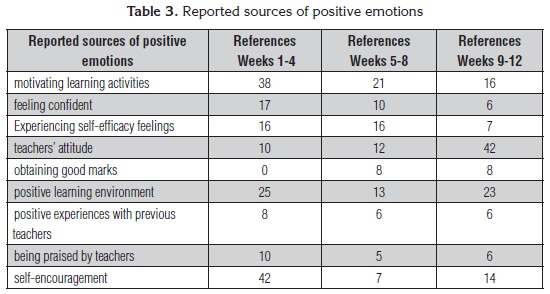

At the end of the 12 weeks, 350 journal entries were on the study file. The data set was analysed in three stages due to its extensiveness. The first stage of analysis included a general reading after students handed in their journal entries every two weeks. A quick read allowed the researcher to have information about the emotions experienced, as well as the events originating these emotions. The second stage consisted of a detailed reading in which specific emotions were highlighted and their sources were identified. The analysis of journal entries was then divided into three periods throughout the term. The final analysis provided 14 sources of negative emotions (see Table 2) and nine sources of positive emotions (see Table 3) reported by students. The results in the following section will therefore be presented in the three stages in which these were analysed: weeks 1-4; weeks 5-8 and weeks 9-12.

Results

Students reported a vast number of emotions during the term. These emotions were both negative and positive, and were originated by different sources. In order to aid readability, the results are presented first by introducing the range of positive and negative emotions students reported during the study period. Then, following the three periods of analysis, the perceived causes of negative emotions are presented with the number of references reported for each of these. In a later section, perceived causes of positive emotions will be presented, again following the three periods of analysis.

Although students experienced both types of emotions, negative emotions predominated during the term. Students' self-reports on emotional experiences identified two main sources of these in foreign language learning instruction: the teachers' impact, and the learning environment impact. The students' journal entries described many instances of how these two aspects impacted their performance in daily classes. Teachers have been widely recognised in literature as the main source of students' emotions, which is understandable due to the leading role they exercise in a classroom. The classroom climate has also been identified as an important feature of effective learning; thus it is not surprising that students made constant references to the learning environment when they considered this to be enhancing or detrimental to their language learning process. These two aspects will be discussed in the section on implications for language teachers, below.

Discussion of results

Phase I: weeks 1-4

Students reported feeling more negative than positive emotions during the first four-week period. The negative emotions reported the most were: fear, worry and sadness. Students reported being afraid of being laughed at while participating in class activities, worried about not being able to understand everything the teachers were explaining, and sad about their lack of vocabulary, which restricted their participation in class. From their first journal entries there were references to a proficient group of students in the class who were more fluent when speaking in English. This caused students to realise that they needed to invest more time in their language learning process since they needed to develop their language abilities. It was because of this that students started to develop a sense of responsibility towards their language learning process, which in turn led them to develop learning and motivational strategies from the very first week of the term. Reflection seemed to also have started early in the term because of a critical incident that most students reported in the third week, regarding the marking system a teacher used in a writing task. This episode seemed to have affected the course, as some students reported feeling different after this event occurred in class. Thus a very negative environment seemed to have developed in this particular class.

Phase II: weeks 5-8

Emotions during this period of the study were mostly originated by exams, since it was the time of midterms. Negative emotions were originated by feeling frustrated about not being able to interact with fluency in a language task or an oral exam. Students tended to get angry at themselves because of their low performance in a class activity or an oral exam. They evaluated themselves by making comparisons with their classmates. Also during this period there were the first references to some attitudes and gestures from teachers which seemed to have a very negative effect on students' motivation. Another source of their negative emotions was realising that they were in the middle of the term and that their language proficiency was increasing at a very slow pace. They started to worry about their future in the degree, which made them question their permanence in it. The difficulty of some topics provoked negative emotions, as the students felt they were not capable of learning a foreign language. There were also some references to family situations that made them feel sad or worried. Some students reported having economic limitations that interfered with their concentration in classes and also with their attendance to university.

Phase III: weeks 9-12

Negative emotions were originated by the proximity of the end of the term and the final exams students were about to take. Students were making comparisons among the different teaching approaches and this made them feel angry at some teachers. Some attitudes and gestures from one teacher were considered intimidating; students were now not only comparing their oral performance but also their exam marks which led some to feel disappointed and upset. Some students felt bored because of certain activities; students began to be critical about being told that they were doing well in their learning process while this subjective evaluation was not reflected in their marks. Although having to be in front of the group speaking in English still originated fear and nervousness, it seemed that a change had happened, as students saw their nervousness and fear as something that they had to overcome; they felt a bit more confident due to having acquired new structures and vocabulary that they could use in their class activities.

Phase I: weeks 1-4

Students also experienced positive emotions which were mostly provoked by motivating learning activities that caused feelings of self-efficacy, thus re-energising their motivational energy. Students felt happy about being able to participate in a group where they felt confident. They also expressed feeling happy about obtaining good marks in written tasks or quizzes. The recognition of the development of their language abilities was also another enhancer of positive emotions. In addition, some activities were very dynamic and originated excitement and motivation in students to continue with their language learning classes and activities. Being in a class where the teacher made them feel confident originated in them self-efficacy feelings to be able to speak English and finish the degree. According to some students, the attitude of a teacher towards a class is the only aspect that will determine the acceptance or rejection of a teacher.

Phase I: weeks 5-8

Emotions during this period of the study were mostly originated by exams, since it was the time of midterms. Positive emotions were experienced due to class activities that students considered fun. Some students also experienced feeling more confident in class when working in small groups with students they got along with. Some reported realising that they were learning and could attest to their advancement in class activities or participation. Realising their language proficiency was advancing made them feel happy and confident in their abilities to be good professionals in the near future. Being able to obtain good marks in exams made some students experience feelings of self-efficacy, and their selfconfidence to finish the degree increased. Most positive emotions originated in this phase due to students getting good or very good marks in the exams which had made them worry a lot during this period.

Phase III: weeks 9-12

This period seems to be more dominated by positive emotions. Positive emotions were present after a class activity that stirred up their interest in the language. Students continued feeling good after being in a small group where they could interact with confidence since they got along with the other people in it. Attitudes from the teacher influenced how they acted in class activities; students compared two teacher approaches and how they felt secure in one environment while in the other they felt insecure and embarrassed to try. Being praised by a teacher in a positive way elicited happiness and confidence. A positive attitude towards their mistakes and fear developed, since they now considered mistakes and fear to be a natural step in their language learning process. Students seemed to have developed not only responsibility but also awareness of the implications of learning a foreign language.

Pedagogical implications

As reported inthe previous section, studentperceived causes of emotions are diverse. The emotions experienced by students during classroom instruction are also vast. However, the two main aspects identified as impacting on students' emotional experiences are: the teachers' attitudes, and the classroom climate.

Teachers as a main source of emotions in classroom settings

Different authors on emotions research in education agree on the influence of the context, the person's current experiences, and external sources such as peers and teachers on students' feelings and emotions (Efklides and Volet, 2005; Gläser-Zikuda et al., 2005; Hascher, 2008; Pekrun et al., 2002). In diverse studies the main source of students' feelings and emotions is the teacher (Gläser-Zikuda and FuB, 2008; Hascher, 2007, 2008; Sansone and Thoman, 2005). Gläser-Zikuda et al. (2005) found that, "the teacher variable explained up to 15% of the variance of emotion variables"(p. 493). Thus they concluded that any emotional intervention has to take into account the personality of the teacher, since he or she is considered to influence any type of educational intervention. Thus, these results are in line with motivation studies in foreign language learning where teachers are said to be the determinant factor influencing students' motivation in instructed learning (Lei, 2007; Tse, 2000; Williams et al., 2004). The link between emotions and motivation is therefore a decisive one in instructed foreign language learning, since the emotions originated in classrooms settings will determine the amount of effort and interest of students in learning tasks, influencing their motivation in this way. As reported by one student:

When teachers tell me something good about my performance, I feel really happy and I was like that all day in my classes. You feel good and motivated...I feel like participating more because I know I am doing things right. (Student 15)

Pekrun et al. (2002) found that positive emotions like enjoyment and pride correlated positively with students' motivation to learn and to achieve goals. Thus positive feelings and emotions originated in classroom instruction seem to trigger in students motivational energy that impels them to act academically in order to achieve their specific goals and to continue experiencing those positive feelings and emotions in future academic goals. According to Scherer (2005) feelings and emotions prepare people to act; this implies that if someone is acting in certain ways, the experience of a feeling or emotion can make him or her stop that particular action (changing their motivational energy) or continue making the best effort possible to achieve a particular goal. Thus the change in motivational energy can be positive or negative, depending on the feeling or emotion experienced. Emotions can help students make more effort in a particular academic situation or can make them stop trying. Feelings and emotions can also help someone to redirect their motivational energy. In the course of academic work, students can find that something really interests them and can focus all their attention and motivation on that particular interest.

Dörnyei (1994) identified three sets of motivational components in foreign language learning situations: course-specific motivational components, teacher-specific motivational components, and group-specific motivational components. The teacher set comprises the following: affiliative drive, authority type, and socialization of student motivation.

Students' motivation may be increased by their desire to please the teacher or their parents because they like or appreciate them, or because they want to minimise their disapproval (Blumenfeld, 1992). Although this spark of motivation is an extrinsic one, it may evolve into an intrinsic one. The teacher authority type is another source of students' motivation fluctuation, it can be supporting or controlling. If students perceive teacher authority as supportive their motivation can be increased, whereas if they perceive it as controlling it may be detrimental to students' motivation (Deci and Ryan, 1985; Littlewood, 2000). As expressed by one student:

The teacher didn't motivate us to participate because he made gestures or certain comments that inhibited me. I didn't like to participate because I felt afraid of the teacher's comments. (Student 9)

The third component refers to the teacher actively enhancing students' motivation through three different channels: a) modelling: teachers as leaders in classroom spaces can directly develop students' motivation through their attitude and effort during classroom instruction; b) task presentation: during presentation of different activities and tasks during classroom instruction, teachers' ability to attract students' attention, state the purpose of an activity and suggest strategies that can be used for successful completion of the tasks can influence students' motivation by incrementing their interest and the effort made in those activities; c) feedback: the feedback approach a teacher employs during classroom activities may enhance or hinder students' motivation. This was clearly expressed by one student:

The teacher asked us to do another piece of homework but I was so afraid because of the feedback in a previous composition that I was writing and I erased it...then I started again but as time passed I felt really bad because every time I did it was worse than before. (Student 4)

Feedback can be informational (helping students' development of weaker areas) or controlling (making judgements about language proficiency of students); the latter should be avoided since it can send negative messages for students' motivation energy by making comparisons with external standards (e.g. native speakers' pronunciation) or group-related standards (e.g. classmates' successes) (Dörnyei, 1994). This practice of social comparison which is widely used in institutions and classroom settings, is considered to be very detrimental to learners' intrinsic motivation (Carole, 1992). Thus making public comparisons between classmates should be avoided, since it can create a very negative environment and hinder group cohesion.

In two recent studies done in the context of China, it is stated that the reticence to speak or participate in classroom activities, which is usually attributed to the cultural and educational environment in which students have developed, is not so enhanced by culture but by the controlling teaching practices imposed on students (Xie, 2010; Zhang and Head, 2010). I believe this is not only relevant to the Chinese context, since in other contexts teachers are also making use of controlling practices when presenting a topic or giving feedback. These findings are consistent with Littlewood's (2000) conclusions that students' interactions in class are modified because they see the teacher not as a facilitator but as an authority figure. From this it can be concluded that students who are taught in a class in which the teacher exercises a controlling authority will have negative emotional experiences, and motivation cannot be generated or enhanced.

Students may feel they have no control over any of the components of their learning process, and emotions of frustration, discouragement and oppression may originate. A way to help students have a sense of ownership and control of their learning is by involving them in identifying their needs and giving them choices for fulfilling them (Graves, 2005). According to Williams and Burden (1997), an important determinant in language learning motivation is this sense of ownership, which may also contribute to personal control and empowerment, increasing students' self-esteem. It is important to give space to student-initiated ideas that most of the time are not allowed or restrained because they do not facilitate teacher control in the classroom (Jackson, 2002). This controlling practice in language classrooms leaves no opportunities for students to develop linguistically and is detrimental to their motivation because there is no space for them to develop their confidence.

Why is a positive classroom climate necessary?

According to Gage and Beliner (1992), "Learning is easiest, most meaningful, and most effective when it takes place in a non-threatening situation" (pp. 480-485). According to different studies in general education and in foreign language learning, the learning environment is another powerful influence on students' emotional arousal, and consequently on the effort exercised in classroom activities (Gläser-Zikuda and Järvelä, 2008; Meyer and Turner, 2006; Pekrun et al., 2002; Yan and Horwitz, 2008). This was a common feeling expressed by the students participating in this study. As some students stated:

Well...this teacher gives you security, confidence and this has helped me a lot because I participate all the time in class... the teacher always asks everyone in the group without making any exceptions. Whereas other teachers....er.....this teacher gives you the confidence to participate without feeling you are being judged. (Student 13)

…the friendly side of a teacher helps us as students to be more motivated because those teachers who care always tell you... you can come to me if you have any doubts and you go to them and they help you and you learn more...this interaction makes you feel good because in some cases teachers are very rigid and don't even smile...and you feel really stressed in these classes and you don't even want to move because the teacher is going to scold you. (Student 5)

Thus it seems that this principle is the foundation to motivating students in classrooms, since the lack of a positive classroom environment is one of the main causes of negative emotions in students in most studies in general education and in foreign language learning in particular, where the learning of a foreign language can be more affectively demanding on students. As stated by Meyer and Turner (2006),

Engaging students in learning requires consistently positive emotional experiences, which contribute to a classroom climate that forms the foundation for teacher-student relationships and interactions necessary for motivation to learn. (p. 377)

According to Turner, Meyer, and Schweinle (2003), a positive classroom climate is essential to the promotion of positive emotions during instructional interactions in classroom settings. This was clearly expressed in the following reference:

...in this class, we all participated...you cannot feel tension in the environment and everything just flows. This teacher made >everyone participate without showing you up when you made a mistake. (Student 6)

It is understandable why the teacher has been shown to be the main cause of emotions in diverse studies. The teacher is the one who sets the principles of classroom structure, selects materials, groups students and establishes rapport among them, so it is his or her interpersonal skills which are going to set the scene for the promotion of a good learning environment. The daily experience of diverse instructional interactions originates different emotions in students which then impact on their motivation (Turner et al., 2003). The promotion of a positive learning environment is a key component of effective teaching and learning. This entails a huge responsibility on teachers who should try to create a positive learning environment and maintain it during a course in order to provide students with a safe environment in which they feel willing to take risks. As stated by Arnold (2009), "an affectively positive environment puts the brain in the optimal state for learning: minimal stress and maximum engagement with the material to be learned" (p. 146).

Conclusions

The aim of this study was to gain a deeper insight into students' emotional experiences in foreign language learning and instruction. Results showed that foreign language learners experience an array of negative and positive emotions during classroom instruction. Although students reported more negative than positive emotions during the study period, these were not detrimental to their motivational energy to finish the ELT programme. However, negative emotions decreased students' participation in classes due to their fear of being laughed at by their peers or being negatively evaluated by teachers. The negative emotions more reported by participants of the study were: fear, worry, nervousness, sadness, anger, frustration, insecurity, anxiety and boredom. These negative emotions were originated by diverse situations such as: fear of being laughed at while participating in class, fear of being mocked by their peers, worry about not being able to understand teachers, sad about their lack of vocabulary, frustrated when not being able to speak fluently in class activities, angry at themselves when not performing as expected in class activities, feeling down when comparing with their advanced peers, angry at some teacher approaches and grading systems, bored with some learning activities, sad because of some family situations, and worry about the lack of financial resources some were experiencing.

Positive emotions were also experienced during the 12 week period of the study. Positive emotions more reported by students were: happiness, calmness, excitement, confidence, satisfaction and relaxation. These emotions were originated by learning activities that students found motivating, teachers' attitudes that made students feel cared for, the positive learning environment developed by some teachers in classrooms, feeling confident when performing in front of the class, and experiencing feelings of self-efficacy after completing a task activity or exam.

The importance of this research was in displaying foreign language learners' emotional experiences during instruction and showing how these experiences impacted on their motivation. The findings of the study reported the great impact teachers have on students' motivation and on the learning environment. Results of the study indicate that there is a definite need for foreign language teachers to review their teaching practices in order to address students' emotional experiences in classrooms. This may provide a challenge to practising teachers, who may think that is not their job to cater to learners' affective needs. However, emotions have been revealed as strongly impacting on foreign language learners' motivation not only in classroom instruction (Garret and Young, 2009), but also in individualised settings (Bown and White, 2010). A positive teacher attitude and appropriate interpersonal skills are important, as reported by participants in this study. Reflection on previous teaching experiences can be helpful in identifying areas that teachers need to work on. By showing commitment towards helping students learn, teachers can make a difference in students' everyday motivation. Students revealed the importance of being supported in those individual areas that needed reinforcement. By providing students with extra practice in those particular areas, teachers can show students they care about their learning development.

Language learning is a process replete with negative and positive emotions, thus appropriate management of students' emotions is necessary for language teachers to enable them to help their students make their emotions work for them and not against them. The importance of creating a positive classroom climate in which students feel secure and willing to take the risks inherent in learning a foreign language is a paramount skill teachers need to work on. Teachers need to develop strategies to make the learning environment a supportive one in which students feel confident and willing to participate. Establishing respectful and positive human relations is not an easy task, not only in the academic field, but in any aspect of human life. Thus, it is important for teachers to enforce effective techniques that can contribute to the establishment and maintenance of positive interpersonal relations in any instructional situation.

References

Aki, O. (2006). Is emotional intelligence or mental intelligence more important in language learning? Journal of Applied Sciences, 6 (1), 66-70.

[ Links ]Arnold, J. (2009). Affect in L2 learning and teaching. Estudios de Lingüística Inglesa Aplicada, 9, 145-151.

[ Links ]Arnold, J. (Ed.). (1999). Affect in language learning. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

[ Links ]Arnold, J., & Brown, D. H. (1999). A map of the terrain. In J. Arnold (Ed.), Affect in language learning (pp. 1-24). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

[ Links ]Barbour, R. (2008).Introducing qualitative research: A student guide to the craft of doing qualitative research. London: Sage.

[ Links ]Bailey, K. M. (1983). Competitiveness and anxiety in adult second language learning. In H. W. Seliger & M. H. Long (Eds.), Classroom oriented research in second language acquisition (pp.67-102).New York: Newbury House.

[ Links ]Bandura, A. (1997). Self-efficacy: the exercise of control. New York: W. H. Freeman and Company.

[ Links ]Bown, J. & White, C. J. (2010) Affect in a self-regulatory framework for language learning. System, 38 (3), 432-443.

[ Links ]Blumenfeld, P. C. (1992). Classroom learning and motivation: clarifying and expanding goal theory. Journal of Educational Psychology, 84(3), 272-281.

[ Links ]Carole, A. (1992). Classrooms: Goals, structures and students motivation. Journal of Educational Psychology, 84(3), 267-271.

[ Links ]Covington, M. V. (1992) Making the grade: a self-worth perspective on motivation and school reform. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

[ Links ]Deci, E. L., & Ryan, R. M. (1985). Intrinsic motivation and self-determination in human behavior. New York: Plenum.

[ Links ]Dewaele, J. M. (2005). Investigating the psychological and emotional dimensions in instructed language learning: Obstacles and possibilities. The Modern Language Journal, 89(3), 367-380.

[ Links ]Do, S. L., & Schallert, D. L. (2004). Emotions and classroom talk: Toward a model of the role of affect in students' experiences of classroom discussions. Journal of Educational Psychology, 96(4), 619-634.

[ Links ]Dörnyei, Z. (1994). Motivation and motivating in the foreign language classroom. The Modern Language Journal, 78(3), 273-284.

[ Links ]Dörnyei, Z. (2001). Motivational strategies in the language classroom. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

[ Links ]Dörnyei, Z. (2005). The psychology of the language learner: Individual differences in second language acquisition. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.

[ Links ]Dörnyei, Z. (2009). The L2 motivational self-system. In Z. Dornyei, & E. Ushioda, (Eds.), Motivation, language identity and the L2 self (pp. 9-42). Clevendon: Multilingual Matters.

[ Links ]Efklides, A., & Volet, S. (2005). Emotional experiences during learning: multiple, situated and dynamic. Learning and Instruction, 15(5), 377-380.

[ Links ]Ekman, P. (2003). Emotions revealed: Understanding faces and feelings. London: Weidenfeld & Nicolson.

[ Links ]Ellis, R. (1994). The study of second language acquisition. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

[ Links ]Erickson, E. H. (1968). Identity, youth and crisis. New York: Norton.

[ Links ]Fridja, N. H. (1988). The laws of emotion.American Psychologist 43(1), 349-358.

[ Links ]Forgas, J. P. (2001) Handbook of Affect and social cognition. London: Erlbaum.

[ Links ]Gage, N., & Beliner, D. (1992). Educational psychology (5th ed.). Boston: Houghton Mifflin.

[ Links ]Gardner, R. C. & Lambert, W. E. (1972). Attitudes and motivation in second language learning. Rowley, Massachusetts: Newbury House Publishers.

[ Links ]Garret, P. & Young, R. F. (2009) Theorizing affect in foreign language learning: an analysis of one learner's responses to a communicative Portuguese course. The Modern Language Journal, 93 (2), 209-226.

[ Links ]Gläser-Zikuda, M., & FuB, S. (2008).Impact of teacher competencies on student emotions: A multi-method approach. International Journal of Educational Research, 47(2), 136-147. [ Links ]

Gläser-Zikuda, M., FuB, S., Laukenmann, M., Metz, K., & Randler, C. (2005). Promoting students' emotion and achievement -instructional design and evaluation of the ECOLE-approach. Learning and Instruction, 15(5), 481-495. [ Links ]

Gläser-Zikuda, M., & Järvelä, S. (2008). Application of qualitative and quantitative methods to enrich understanding of emotional and motivational aspects of learning. International Journal of Educational Research, 47(2), 79-83.

[ Links ]Graves, K. (2005). Designing language courses: A guide for teachers. Beijing, China: Foreign Language Teaching and Research Press.

[ Links ]Hascher, T. (2007). Exploring students' well-being by taking a variety of looks into the classroom. Hellenic Journal of Psychology, 4(3), 331-349.

[ Links ]Hascher, T. (2008). Quantitative and qualitative research approaches to assess student well-being. International Journal of Educational Research, 47(2), 84-96.

[ Links ]Immordino-Yang, M. H. & Damasio, A. (2007) We feel, therefore we learn: the relevance of affective and social neuroscience to education. Mind, Brain and Education, 1(1), 3-10.

[ Links ]Imai, Y. (2010) Emotions in SLA: New insights from collaborative learning for an EFL Classroom. The Modern Language Journal, 94 (2), 278-292.

[ Links ]Jackson, J. (2002). Reticence in second language case discussions: Anxiety and aspirations. System, 30(1), 65-84.

[ Links ]Jacobs, B. (2004). Writing for emotional balance: A guided journal to help you manage overwhelming emotions. Oakland, CA: New Harbinger Publications.

[ Links ]Jensen, E. (2005). Teaching with the brain in mind. Alexandria, VA: ASCD.

[ Links ]Lei, Q. (2007). EFL teachers' factors and students affect. US-China Education Review, 4(3), 60-67.

[ Links ]Littlewood, W. (2000). Do Asian students really want to listen and obey? ELT Journal, 54(1), 31-35.

[ Links ]MacIntyre, P. (2002). Motivation, anxiety and emotion in second language acquisition. In P. Robinson (Ed.), Individual differences and instructed language learning (pp. 45-68). Amsterdam: John Benjamins Publishing.

[ Links ]Meyer, D. K., & Turner, J. C. (2006). Re-conceptualizing emotion and motivation to learn in classroom contexts. Educational Psychology Review, 18 (14), 377-390.

[ Links ]Turner, J. C., Meyer, D. K., & Schweinle, A. (2003). The importance of emotion in theories of motivation: Empirical, methodological and theoretical considerations from a goal theory perspective. International Journal of Educational Research, 39(4-5), 375-393.

[ Links ]Pekrun, R. (2000). A Social-Cognitive, Control-Value Theory of Achievement Emotions. Amsterdam: Elsevier Science B.V.

[ Links ]Pekrun, R., Goetz, T., Titz, W., & Perry, R. P. (2002). Academic emotions in students' self-regulated learning and achievement: a program of qualitative and quantitative research. Educational Psychologist, 37(2), 91-105.

[ Links ]Sansone, C., & Thoman, D. B. (2005). Does what we feel affect what we learn? Some answers and new questions. Language and Instruction, 15(5), 507-515.

[ Links ]Scherer, K. R. (2005). What are emotions? And how can they be measured? Social Science Information, 44(4), 695-729.

[ Links ]Schumann, J. H. (1998). The neurobiology of affect in language. Oxford: Blackwell.

[ Links ]Schutz, P. A., & DeCuir, J. T. (2002). Inquiry on emotions in education. Educational Psychologist, 37(2), 125-134.

[ Links ]Tse, L. (2000). Student perceptions of foreign language study: A qualitative analysis of foreign language autobiographies. The Modern Language Journal, 84(1), 69-84.

[ Links ]Weiner, B. (1992). Human motivation: metaphors, theories and research. Newbury Park, CA, Sage.

[ Links ]Williams, M., Burden, R., Poulet, G., & Maun, l. (2004). Learners' perceptions of their successes and failures in foreign language learning. Language Learning, 30(1), 19-29.

[ Links ]Williams, M., & Burden, R. L. (1997). Psychology for language teachers: A social constructivist approach. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

[ Links ]Xie, X. (2010). Why are students quiet? Looking at the Chinese context and below. ELT Journal, 64(1), 10-20.

[ Links ]Yan, J. X., & Horwitz, E. K. (2008). Learners' perceptions of how anxiety interacts with personal and instructional factors to influence their achievement in English: A qualitative analysis of EFL learners in China. Language Learning, 58(1), 151-183.

[ Links ]Zhang, X., & Head, K. (2010). Dealing with learner reticence in the speaking class. ELT Journal, 64(1), 1-9. [ Links ]