Services on Demand

Journal

Article

Indicators

-

Cited by SciELO

Cited by SciELO -

Access statistics

Access statistics

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in

SciELO

Similars in

SciELO -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Profile Issues in Teachers` Professional Development

Print version ISSN 1657-0790

profile vol.15 no.1 Bogotá Jan./Apr. 2013

The Role of Collaborative Work in the Development of Elementary Students' Writing Skills*

El papel del trabajo colaborativo en el desarrollo de las habilidades de escritura de estudiantes de primaria

Yuly Yinneth Yate González*

Luis Fernando Saenz**

Johanna Alejandra Bermeo***

Andrés Fernando Castañeda Chaves****

Corporación Colegio San Bonifacio de las Lanzas, Colombia

* yuly.yate@sanboni.edu.co

** luis.saenz@sanboni.edu.co

*** johale238@yahoo.com

**** andres.castaneda@sanboni.edu.co

This article was received on July 1, 2012 and accepted on January 12, 2013.

In this article we report the findings of a two-phase action research study focused on the role of collaborative work in the development of elementary students' writing skills at a Colombian school. This was decided after having identified the students' difficulties in the English classes related to word transfer, literal translation, weak connection of ideas and no paragraph structure when communicating their ideas. In the first phase teachers observed, collected, read and analyzed students' written productions without intervention. In the second one, teachers read about and implemented strategies based on collaborative work, collected information, analyzed students' productions and field notes in order to finally identify new issues, create and develop strategies to overcome students' difficulties. Findings show students' roles and reactions as well as task completion and language construction when motivated to work collaboratively.

Key words: Collaborative learning, writing in elementary school, writing process.

Presentamos los resultados de una investigación-acción llevada a cabo en dos fases, centrada en el papel del trabajo colaborativo en el desarrollo de habilidades de escritura de estudiantes de primaria en una escuela colombiana. El estudio se realizó tras haber identificado las dificultades de los alumnos en las clases de inglés relacionadas con la transferencia de palabras, la traducción literal, la débil conexión de las ideas y la falta de estructura del párrafo al comunicar sus ideas. En la primera fase los docentes observaron, recogieron, leyeron y analizaron las producciones escritas de los alumnos sin realizar ninguna intervención pedagógica. En la segunda, los profesores leyeron sobre estrategias de trabajo colaborativo y las implementaron; recopilaron información, analizaron las producciones textuales de los estudiantes y las notas de campo tomadas para identificar nuevos problemas, crear y desarrollar estrategias que ayudaran a los estudiantes a superar sus dificultades. Los hallazgos muestran cómo reaccionaron los estudiantes ante el trabajo colaborativo, y asimismo la forma como realizan tareas y construyen su lenguaje cuando están motivados a trabajar de esta manera.

Palabras clave: aprendizaje colaborativo, escritura en primaria, proceso de escritura.

Introduction

This research project seeks to examine the role of collaborative work in the development of elementary students' writing skills in their English classes at the Corporación Colegio San Bonifacio de las Lanzas. Taking into account that elementary school students have not yet started their formal writing process in English, we assessed students to determine their current standing on their ability to write and what they implemented when composing written tasks. Through this, the elementary language teachers would develop the necessary strategies to help students improve and create solid bases for an accurate writing process, as well as establish departure points to improve upon in the years to come.

The authors of this article, who worked in grades 2, 3, 4 and 5, decided to work together in order to find strategies to help students when writing due to an observation made on the performance of elementary students for at least a year. We noticed some difficulties when students wanted to write their ideas in English such as transferring words and expressions from Spanish (using literal translation), reduced or basic vocabulary, weak connection of ideas and no paragraph structure. Also, most of the students showed a lack of interest and were reluctant to compose single sentences (a simple task) as well as get involved in longer assignments.

Many authors have written about the benefits of writing throughout history, remarking on its power and its ability to convey knowledge and ideas (MacArthur, Graham, & Fitzgerald, 2006). Besides, it allows people to express their points of views by making their thinking visible as well as promotes the ability to ask questions, helps others to provide feedback and demonstrates their intellectual flexibility and maturity, among others. On the other hand, collaborative authoring or writing can be defined as the set of activities involved in the production of a document by more than one author (Dillon, 1993). Taking this information about writing and collaborative authoring into account, we try to demonstrate with the following research project the effect of collaborative work as a tool for developing writing skills in elementary students.

Theoretical Framework

Focusing on the objective of this investigation, we approached our research with our focus aimed at three key aspects of study: collaborative learning, the writing process and the development of writing skills in elementary (primary) school.

Collaborative Learning

As stated by Smith and Macgregor (1992),

Nowadays, Collaborative Learning is seen as a powerful tool that provides meaningful experiences for students and teachers, in which learning as a group is the motor that impulses other learning processes. In this type of techniques, teachers are not the ones that possess all the knowledge, and their only purpose is to transmit and reproduce that knowledge, but teachers are considered as promoters of experiences where students discover functionalities in what they learn, share with other and apply that knowledge to their real life.

From a collaborative sense, the real meaning of this technique is not only the generation of students' encounters in which they are given a task to develop, but also are given the opportunity to give opinions, self-correction and peer correction as tools to promote tolerance and idea-sharing, planning projects, among other important benefits of Collaborative Learning. (p. 1)

These are some features of collaborative learning that we would like to highlight, as mentioned by Smith and Macgregor (1992):

- Learning is an active process in which all of its participants provide meaningful ideas for projects to be carried out.

- Learning depends on rich contexts in which students can feel more interested in working as teams with clear goals to achieve.

- Learners are diverse, meaning that every participant may have different ideas, opinions and points of view that can change or improve the project development. (p. 1)

As for education, collaborative learning has developed certain roles and values that we as teachers have to promote in our students when working in collaborative environments (Smith & Macgregor, 1992). These values are later turned into earnings for students. First, collaborative work involves all the participants and makes them work as a team in which the direction of the project is unique. Second, learners learn how to cooperate among themselves, where work is not seen as an individual product, but it is a process in which the participants' ideas influence and have a positive impact on the project, so the participants' contributions are relevant and necessary. And finally, civic responsibility is learnt through the experience on collaborative learning; with this, students comprehend that the world is an enormous field in which some abilities are required to become a successful professional, such as cooperation, working with others, sharing ideas, comparing and contrasting opinions, defining goals, searching for strategies to achieve those goals, and learning from on-hand experience. These previous elements of collaborative learning have shown that learning, seen as an integral process, requires more than knowledge transferred from the teacher; it also requires experience that is learnt through working with others.

The Writing Process

According to Long and Richards (1990), the writing process has been an interesting field for educational researchers, linguists, applied linguists, and teachers since the early 1970s (Long & Richards, 1990), giving as results, numerous projects done in the field, identifying different aspects of this skill in L1 and L2 and their relationship. In the United Kingdom, for example, researchers such as Britton, Burgess, Martin, Macleod, & Rosen (1975) observed young learners in the process of writing in order to identify the planning, decision making and heuristics they employed. Complementary work in the United States by researchers and educators such as Eming, Murray and Graves (cited in Long & Richards, 1990, p. viii) led to the emergence of the "process" school of writing theory and practice. This view emphasizes that writing is a recursive rather than a linear process, that writers rarely write to a preconceived plan or model, that the process of writing creates its own form and meaning (depending on the writers' intention, beliefs, culture, etc.), and that there is a significant degree of individual variation in the composing behaviors of both first and second language writers (Long & Richards, 1990).

Flower and Hayes, and Bereiter and Scardamalia (cited in Myles, 2002) proposed some writing process models that have served as the theoretical basis for using the process approach in both L1 and L2 writing instruction. By incorporating pre-writing activities such as collaborative brainstorming, choice of personally meaningful topics, strategy instruction in the stages of composing, drafting, revising, and editing, multiple drafts and peer-group editing, the instruction takes into consideration what writers do as they write. Attention to the writing process stresses more a workshop approach to instruction, which fosters classroom interaction, and engages students in analyzing and commenting on a variety of texts. The L1 theories also seem to support less teacher intervention and less attention to form.

At the Corporación Colegio San Bonifacio de las Lanzas, the L2 writing process is one of the skills students must develop in their academic performance. Taking into account the nature of our curriculum, we feel writing is an ongoing process students must follow according to a variety of stages of prewriting, drafting, editing and rewriting and finally publishing, varying its levels of difficulty among the grades.

Writing Skills Among Elementary Students

Primary school teachers have been evaluating the importance of writing from the early ages at school throughout many years. Our main concern as EFL teachers yields on how to initiate students from primary levels into the second language writing process and how farther they should go by the end of each school year.

What our research project is looking for basically is how to develop students' writing skills in a collaborative environment, so they can build up the bases and structures to reach good results in academic terms. However, according to Hillocks (1986), we should examine the giving of instructions rather than the way in which we approach students to work in writing. Bazerman (2007) states that

We as teachers need to face three dimensions and challenges for the teaching of writing: the first one talks about the continuing of writing, the second mentions the complexity of writing and the third one makes reference to writing as a social activity. (p. 293)

Writing as a social activity implies working on tasks where all students can surely be involved in imaginative and creative topics in which writing is seen as a social dialogue (Dyson, 2000) as well as a peer collaboration in the classroom (McLane, 1990). Additionally, writing is a way to interact, share and move further into processes at early ages (Kamberelis, 1999). Due to all of the above, we can connect our collaborative writing research project to a social writing environment, engaging and encouraging children to link the classroom activities with real life. Doing so, we can help students to enjoy and become more motivated towards writing.

Considering the previous issues, we came to be concerned about the lack of interest students have in writing, and the difficulties concentrating on main ideas; these difficulties can be identified as not being concise and precise when expressing opinions, not using the correct vocabulary for the activity as well as not keeping track of punctuation, and not having coherence and cohesion when writing.

Context

The population we took into account was the elementary students from Corporación Colegio San Bonifacio de las Lanzas, a private bilingual school with an English class intensity of seven (7) hours per week and a total of 536 students. It is located in the city of Ibagué (Colombia) and serves students of the middle-high socioeconomic status.

School Description

With 26 years of experience, the school is one of the most important educational institutions in the region and it is also known throughout the whole country because of its high academic performance shown in the results of national tests and because our eleventh grade students rank in the highest levels based on the standards of the European Council (Council of Europe, 2001).

Taking a brief look at the overall framework of the School Institutional Project (Proyecto Educativo Institucional = PEI) regarding the use of a foreign language, it states that the mastering of English as a second language is the main objective of the school. Also, the school is engaged in the intensive learning of the language of globalization as a way to promote the school and its student body internationally. Hence, the School Institutional Project explains that mastering a second language is the minimum standard to be met for educational institutions (Corporación Colegio San Bonifacio de las Lanzas, 2011).

The school has about 75 teachers in areas such as science, social studies, mathematics, English, physical education, arts and language arts. On the other hand, the student population comprises pre-school, elementary, junior high and high school students. In addition to the English class intensity of 7 hours per week, mathematics and science are oriented in this foreign language as well.

Population Description

There are 2 courses per grade in elementary: two second, third, fourth and fifth grades, with a minimum of 18 and a maximum of 29 learners in each classroom. Their ages range from 7 to 12 years old, with varied English language skills due to their previous knowledge learnt from preschool within the institution. The population taken into account consists of 8 students per level, that is to say, 4 students from grade 2A, 4 students from grade 2B, 4 students from 3A, 4 students from grade 3B; 4 students from 4A, 4 students from grade 4B; and 4 students from 5A, and 4 students from grade 5B, all selected at random.

Elementary students start developing their writing and reading skills in second grade at a basic level, that is to say, reading and writing very short but structured single sentences. After that, moving to third grade, they start with the production of simple paragraphs, being encouraged to give opinions and to start developing independent sentences and short paragraphs. Teachers always support and help students to improve their performance including writing skills; this process moves forward and gets more rigorous along with students' elementary school life.

The institution's commitment is to develop a bilingual education. Likewise, and taking into account that Spanish is the L1 of our students and that their processes in learning a second language can be difficult for them to be developed with authenticity in our context (as they are with learning L1), we find the institution's commitment is to develop a step-back process, that is, ensuring that the oral and written linguistic skills in their native language are developed first, and then move on to the process of learning a second language.

Taking that into account, we know the Spanish curriculum and the students' prior knowledge con-tribute to a base for the English curriculum, which aims to develop critical thinking skills (sequencing, analyzing, inferring, summarizing, etc.) and communicative competences (grammatical, discursive, sociolinguistic and strategic) through three principal strands which are the daily and media communication, approaching scientific knowledge and aesthetic and cultural expression. These involve five kinds of discourse which are the narrative, argumentative, descriptive, explanatory and future forms; these are composed of the formal aspects of the language like grammar, syntax, phonology, semantics and the use of language in order to achieve effective communication (see Figure 1).

As we can see from the last lines, more than learning a second language, the approach at San Bonifacio School consists of the effective use of English in real contexts by developing several skills through elements like authentic performances and learning for understanding. All the elements mentioned above along with collaborative work will help students reach their goal, in this case, when writing.

Research Design

This is a study based on the principles of action research and is carried out in a descriptive-innovating manner in which we examined the main contributions of collaborative work in primary students in the development of writing skills.

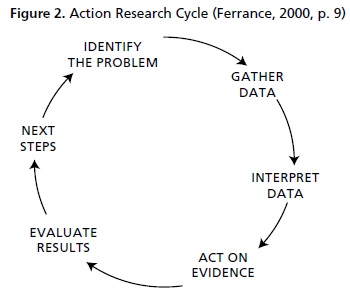

Our research was developed in two stages, following the action research cycle represented in Figure 2. The first stage took place during 2011. Teachers observed, collected and read students' written productions without their intervention concerning collaborative work. The intention of such decision was to gather information about the most common characteristics students have when writing in English. Teachers applied a survey to students on how they felt in relation to writing in English, talking about feelings, likes and dislikes when they write during the English classes (see Figure 31).

In a second stage developed during 2012 and following the action research cycle represented in Figure 2, teachers read about strategies based on collaborative work and selected three strategies that were believed by the teachers to improve students' writing and at the same time overcome the difficulties that may arise during the process. Teachers designed an activity in which they confronted the theory and the practice of collaborative work with primary students; at the same time, teachers gathered information from the students' productions during all this process. Furthermore, teachers analyzed students' productions and teachers' field notes. Finally, teachers identified new issues in order to create and develop strategies to help students overcome difficulties.

Data Collection

For developing phase number one (observation, data collection and data analysis - 2011) and phase number two (act on evidence, strategies implementation, evaluate results, 2012) for the project, teachers selected students' written productions done during the second and the third academic period as sources of information. Teachers created a goal for students to achieve according to the institutional needs. During the writing process students had to follow the processes of planning, drafting, revising and editing, and through these, teachers observed, took notes (using the observation chart in Figure 4) and implemented the following strategies:

- The team plans and outlines the task, then each writer prepares his/her part and the group compiles the individual parts, then revises the whole document as needed.

- One person assigns the tasks, each member completes the individual task, and one person compiles and revises the document.

- As a team, students compose the draft, revise it and make necessary changes.

Findings

During the first phase of our research, we analyzed our findings from the students' classwork, and then grouped our findings into four categories of observation: Students' roles, Task completion, Language construction and Students' reactions (see Table 1). As part of an on-going research, we found some interesting information regarding the differences or rather the fluctuation of responsibilities among students from different grade levels. Next, we analyzed each aspect and resumed our findings being specific onthe abilities being worked and developed.

Students' Roles

Elementary students at the San Bonifacio de las Lanzas School have clear and marked characteristics regarding their roles while working collaboratively. During the analysis of the four categories we have done, there are specific features that let us describe our students' abilities, reactions and language situations involved inside a teamwork writing process. We will describe each of the most relevant factors related to student's roles. We want to focus only on the four main roles and behaviors that caught our attention:

- Students choose their own roles

- Students vote for a leader

- One student takes the initiative

- Students' roles as readers and writers

First, elementary students are able to provide supported reasons why they choose certain roles inside a group during team work. For instance, the case in which students choose their own roles, they do so while considering certain parameters or characteristics they should have in order to perform that role, such as: the best English in the group, the best writer, the best reader or the best editor.

In a different case concerning teams in which students need someone to encourage the team performance, students vote for a leader. In this case, pretty similar to the one mentioned before, students state their choice on specific parameters for that leader to carry on and guide the task completion. Some of the mentioned characteristics are: the best English inside the group, the most organized person, and students' reliance on their abilities to perform different tasks.

Also, on a team in which no one seems to ignite the labor, there is one student who takes the initiative and, without being previously chosen, gets people to work. Perhaps this is the most intriguing case because the one who takes the initiative is not always the student with the best English inside the group. Contrary to the previous "Roles", in which someone is guiding the pro-ject, this student makes him/herself part of the team and develops part of the task. As already mentioned, this student may not be the best at English, but his or her initiative moves the team towards the completion of the task. In this case, after being motivated, students spontaneously choose a role and perform it. Students help each other and carry out the project as a whole group. Students learn about peer-correction and peerwork while developing the task. We can state that there is meaningful and spontaneous learning taking place among the students while they help each other.

In the last case, students seem to be more decisive as to what they want to do while working and being part of a group. In this stage students know exactly what their abilities are and what they are capable of. Students then decide to perform the roles of readers and writers. Students recognize their strength either reading or writing and this helps them organize the group more quickly.

Task Completion

There exists a great range of characteristics that label each one of the different grades in terms of task understanding and completion. However, elementary students have a clear idea of what a task is and how they have to complete it: students read the instructions, ask for clarification, divide tasks and compile the results to present a final production, either orally or written. For this activity, there is a step-by-step process that nearly all the grades follow, and this process is the one we want to focus our attention on. The process is organized as follows:

- Reading and understanding instructions

- Asking for clarification (does not apply in all the cases)

- Gathering ideas

- Dividing tasks

- Compiling results

- Presenting final production (orally and/or written)

The groups start developing the task by reading the instructions; one student reads the task as the other team members listen to the reader. In some cases, students do not understand what they have to do and ask for clarification, either the teacher or their peers. It was crucial to identify that all the groups feel the real need to understand what they have to do. After reading the

task, students gather ideas to perform the task. The fact that students always consider their partners' ideas was very clear to us. Students collect all the ideas and then decide upon the best and the most suitable ones for the task. Along with this, students assigned specific roles inside the groups. These roles are chosen depending on a member's abilities to perform different tasks (the best to do this or that).

Having understood the task, students move to divide the task for all the members (equal duties). In some cases, one student assigns the sub-tasks and in other cases, one student performs or develops the task as the other team members tell them what to do. After this, the group collects the previous results for the task, reads each of the pieces and agrees on possible changes or adjustments. Students become their own supervisor of their written and oral productions. Some groups tend to make adjustments to their productions at this point, while some other groups seem to be more tolerant and less objective towards their partners' contributions (not to hurt others' feelings).

When students finish reading the pieces for the task, they compile the information and present the product. At this point students check for organization and presentation of the final paper. In some groups one student is in charge of collecting, compiling and writing the final production, but other groups choose one person to write the final paper as the rest of the team has already accomplished their initial task. It was a surprise for us to find such process among all the grades. Students have a great management of time and execution to complete the given tasks. They are very careful about the duties they have to perform and how they will do it.

Language Construction

At San Bonifacio de las Lanzas students have a clear sense of the work being implemented in class in order to improve their oral language and writing; doing so has some aspects that enable us as teachers to observe, analyze and identify strengths and areas of improvement in students' daily productions and performance. Given the nature of our day-to-day work, we, as an investigation group, have identified collaborative work as part of an on-going performance to aid us in the construction of a language base.

The focus of this analysis lies within students' language construction, from the basics of their phonetic level to fluent speaking, from simple words to complex sentences. During this phase of students' work, we have identified as follows several important aspects that vary with each level (grade):

- Use of previous knowledge to conceive knowledge.

- Use of Spanglish to understand or be understood.

- Tools used to aid in learning; dictionary, monitors, teacher, etc.

- Notion of correction of common mistakes.

- Punctuation and grammar.

Students from the lowest level come with a notion of things and their surroundings; this helps them understand much of what is being worked in class whether it is visual or conceptual. Students also work together to make the understanding of a specific topic easier. Although this happens more often in lower grades, the exercise is present among all grades. Although the use of a dictionary slowly declines as the grade level increases, students use a variety of tools or methods to understand; the resource used most often is the teacher; s/he is asked for help with translation or spelling.

The use of Spanglish (a mixture of Spanish and English) is noticeable among third to fifth grades; students begin to resort to code switching to make themselves understood, often during all the activities in class; students will refer to their first language to complete sentences being constructed, or even specific words that are unknown to them. Students often feel comfortable and find it easier to code switch because it eases the fluency of speech; however, at some point they realize that knowing the word will help them even more; so during their speech or conversation, students will often ask "How do you say" in order to complete their ideas.

Students have adapted a notion about words and structures that enables them to interact with their writing as it progresses. Some of the most common mistakes students make at San Bonifacio de las Lanzas are the lack of completion of sentences (fragmenting) or the use of run-on sentences. When it comes down to punctuation and grammar, students have issues identifying when to rely on them for each context; while conversing with students they manifested that this was due to a confusion of language context; they assume that in English, rules derived from Spanish do not apply.

Students' Reaction

At San Bonifacio de las Lanzas students are committed to learning through a variety of means implemented in class as part of the pedagogical method. Part of students' identity could be defined as the development of students' different skills through ample fields of learning such as debates and round table discussions, among others.

The focus on this analysis lies in the reaction of each student or students as a whole to identify their functions, based on previous data collection, taking into consideration peer to peer interactions. We have identified some key aspects related to this investigation, namely:

- Group interaction

- Life experiences

- Positive reinforcement

- Teacher-student interaction

As part of our research we have identified group interaction to be essential when students brainstorm for possible writing topics; appreciating different ideas gives students a broad view of what to come up with in regard to composing texts. Students enjoy time in class specially when their ideas are heard and appreciated; giving them the opportunity to interact with one another empowers them with trust and confidence to participate, positively contribute and overcome difficulties at the speaking level.

One of the most common difficulties students faced during group interaction was the difference of ideas between boys and girls among low grade levels (2nd and 3rd). Students' ideas differ at the cohesion level; what this means is that boys' ideas were somewhat "out in the open" whilst girls' ideas were direct and concise, each relating to the activities planned.

Between the ages of 8-11 years old, students' life experiences help them relate to activities planned and executed during their learning period. This gives students an opportunity to take ownership of whichever activity they are undertaking and feel encouraged to brainstorm, write and share.

As part of a group interaction during each and every moment of writing as well as oral and listening activities in class, teachers and students are always communicating, therefore providing valid information about performances in all of the different fields. Students rely a lot on feedback to positively construct their work; hence, teacher collaboration and involvement during these activities is essential. Some students also feel the need within their "group" to receive positive comments, observations and interpretations. This need we have identified to be very motivating and encouraging for almost all students.

As always, students follow a very interesting "emotional" line through their elementary performances, from motivated to creative, from curious to enthusiastic; these are all remarkable aspects to keep in mind when viewing each student's work as an individual first and then as part of a group, and it allows teachers and evaluators to monitor, write down and share this very important piece of knowledge.

As a last point of reference, having students' involvement, eye contact, questioning and answering becomes a progressive activity because almost every time, students are advancing more and more through their performances, learning and getting used to new methods to do things.

Conclusions

The implementation of the three strategies for working collaboratively showed interesting results. In the first place, when the team plans and outlines the task, each writer prepares his/her part and then the group compiles the individual parts and revises the whole document as needed. Students felt less comfortable when they felt that their ideas might not be heard or determined, and this prompted them not to speak or interact with the other members of the team in a natural and harmonic way. Some discussions flew around the group environment but students finally seemed to understand that the group task prevails over their own or individual interests (students' roles).

Also, the teams adequately managed time and the subdivisions of the task to comprehend the given work. Students still focused their attention on completing the task and dividing the amount of work so that everyone had their own part and the team achieved its goal (task completion). In addition, students seemed to rely more on their partners' corrections and contributions than on their teachers'. For this strategy, each one of the members of the team maintained a close relation with their team colleagues to the point that language interaction, correction and construction comprised an essential and innate state of the group (language construction).

In second place, when one person assigns the tasks, each member completes the individual task e.g. one person compiles and revises the document in question. Students adopted different roles but a specific feature that remained was evidenced whereby students seemed to feel more comfortable when they performed a role for which they had the best talent or ability (writer, idea proposer, leader, compiler, editor). For this strategy and, as teams had no leaders, the groups decided to assign roles considering their members' abilities for different tasks (students' roles).

As such, students comprehend the relevance and importance of their contributions to the initial task. Members of the teams felt comfortable working on their own with no observer carefully watching what they had to do; instead, team members preferred to consider their colleagues a supportive axis concerning the task completion, an axis on which they could rely and trust in order to understand better the task intention and how to develop it (task completion). One student of the team was the one who provided final feedback on the members' contributions, which made the rest of the team a bit unsatisfied due to the poor and not so reliable feedback. As the only voice that was heard at that point was the editor's, the team had not much to do in terms of correction and revision. Language use and function was directly used in terms of oral feedback. Written language was used only to correct and edit the document (language construction).

In third place, when the team plans and outlines the task and writes a draft, the group revises the draft, thus students feel that their contributions for the task are relevant and considered when developing either of the task subdivisions. No student performed a specific role so that everyone could contribute and have his/her own ideas on what to do and what not to do considered by the others (students' roles).

Also, working with this strategy, ideas flew around the team environment providing a much wider view of what the task intended to achieve and the best methods to do so. Each one of the students assumed one of the task subdivisions, contributed to the task completion with his/her ideas, comments or suggestions, and provided feedback, orally and in writing, for their classmates. Students' interaction happened in a more natural way and this allowed the task to be completely achieved (task completion). In addition, language was freely used by every member of the team. Students used the language to communicate ideas, correct each other, provide accurate feedback on the paper's progress and edit a final version of the paper. For complete achievement of the task students got a clear idea of how important it was to help each other and provide accurate and grounded feedback that help the team reach their initial goal (language construction).

As we could see, at San Bonifacio de las Lanzas, collaborative learning is an opportunity for students to help each other to construct meaning and knowledge, as they work on tasks that demand analyzing, planning, acting and reflecting on their work as a tool to measure their capacity to work with others, and their abilities and contributions as regards common tasks.

Finally, through this research teachers noticed how relevant and meaningful collaborative learning is in students' learning process. So, we can move towards the intention of this type of approach in Education, and more important, the role of Education around Collaborative Learning.

* This paper reports on a study conducted by the authors while participating in a Teacher Development Program led by the PROFILE Research Group of Universidad Nacional de Colombia. The Program was sponsored by the Corporación Colegio San Bonifacio de las Lanzas (Ibagué, Colombia) 2010-2012.

1 The questionnaire was originally administered in Spanish–the students' mother tongue–and translated into English for the purpose of this publication.

References

Bazerman, C. (2007). Handbook of research on writing: History, society, school, individual, text. New York, NY: Lawrence Erlbaum. [ Links ]

Britton, J., Burgess, A., Martin, N., Macleod, A., & Rosen, H. (1975). The development of writing abilities. London, UK: Macmillan. [ Links ]

Corporación Colegio San Bonifacio de las Lanzas. (2010). Plan de Área Inglés. English Area. Ibagué, CO: Author. [ Links ]

Corporación Colegio San Bonifacio de las Lanzas. (2011). Proyecto Educativo Institucional (PEI). Ibagué, co: Author. [ Links ]

Council of Europe. (2001). The Common European framework of reference for languages: Learning, teaching, assessment. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. Retrieved from http://assets.cambridge.org/052180/3136/sample/0521803136WS.pdf [ Links ]

Dillon, A. (1993). How collaborative is collaborative writing? An analysis of the production of two technical reports. In M. Sharples (Ed.), Computer supported collaborative writing (pp. 69-86). London, UK: Springer-Verlag. [ Links ]

Dyson, A. (2000). On refraining children's words: The perils, promises, and pleasures of writing children. Research in the teaching of English, 34(3), 352-367. [ Links ]

Ferrance, E. (2000). Action research cycle. Providence: Northeast and Islands Regional Educational Laboratory at Brown University. Retrieved from http://www.lab.brown.edu/pubs/themes_ed/act_research.pdf [ Links ]

Hillocks, G. Jr. (1986). Research on written composition: New directions for teaching. Urbana, IL: NCTE. [ Links ]

Kamberelis, G. (1999). Genre development: Children writing stories, science reports and poems. Research in the Teaching of English, 33(4), 403-460. [ Links ]

Long, M., & Richards, J. C. (1990). Second language writing. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press. [ Links ]

MacArthur, C., Graham, S., & Fitzgerald, J. (2006). Handbook of writing research. New York, NY: Guilford Press. [ Links ]

McLane, J. B. (1990). Writing as a social process. In L. C. Moll (Ed.), Vygotsky and education (pp. 304-318). Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. [ Links ]

Myles, J. (2002). Second language writing and research: The writing process and error analysis in student texts. TESL-EJ Teaching English as a Second or Foreign Language, 6(2). Retrieved from http://www.cc.kyoto-su.ac.jp/information/tesl-ej/ej22/a1.html [ Links ]

Smith, B. L., & Macgregor, J. T. (1992). What is collaborative learning? Collaborative Learning: A sourcebook for higher education. Anti essays. Retrieved from http://www.antiessays.com/free-essays/81887.html [ Links ]

About the Authors

Yuly Yinneth Yate González is about to obtain a BA in English from Universidad del Tolima, Colombia. She is currently a full-time English Teacher at Corporación Colegio San Bonifacio de las Lanzas, Ibagué, Colombia. Her interests include issues related to action research and applied linguistics.

Luis Fernando Saenz is a full-time English teacher at Corporación Colegio San Bonifacio de las Lanzas, Ibagué, Colombia. He is about to graduate from the undergraduate English teaching program at Universidad del Tolima (Colombia).

Johanna Alejandra Bermeo holds a BA in English from Universidad del Tolima, Colombia. She is currently working at Berlitz Istanbul (Turkey) as an ESP and EFL teacher and native Spanish language instructor.

Andrés Fernando Castañeda Chaves is a full-time English teacher at Corporación Colegio San Bonifacio de las Lanzas, Ibagué, Colombia. He is a student in the undergraduate English teaching program at Universidad del Tolima (Colombia).