1. Introduction

Consumer loyalty strategies are effective means of promoting increased business profitability through the formation and maintenance of a stable portfolio of long-term users of a service. A relationship is also created by this means, allowing the company to identify needs, preferences, and conveniences (current and future). In alignment with this market trend, this study extends knowledge of loyalty programs, including existing modes, key features, and the management implications that arise from the choice of program mode.

The market for loyalty programs is growing and receiving attention worldwide. American companies invest $1.2 billion annually in loyalty programs [1].

According to the Colloquy Loyalty Census [2], American families actively share in an average of around 12 loyalty programs. Canadians participate in an average of 11.1 loyalty programs associations [3]. In Brazil, found that the turnover of associated companies with loyalty programs grew by 27.1 percent in 2015, reaching $1.6 billion [4].

The use of information technology and marketing analyses, as well as the creation of platforms for interfacing with consumers (mobile devices), have boosted the development of loyalty practices all around the world. This has created new opportunities for research themes involving, for example, new program designs and the management implications arising from the use of these.

The research published up to the present time shows the limitations of the modalities of loyalty programs, their main features, and the managerial implications arising from their application. This may include the scope of the program in relation to the market range and the kind of allegiance intended to be achieved for each modality, and it has been as yet unexplored to date.

To address the limitations of the existing literature, this study describes the modalities of existing programs and their principal features, comparing the advantages and restrictions of each and the market ranges within which each modality operates; proposes a new program modality while providing an illustration of the practical aspects of its use; and identifies what approaches to allegiance are taken as the goal for each type of program (brand loyalty to the store or to the program).

2. Literature review

Consumer loyalty is stimulated by a set of integrated actions that reward consumers for repeat business with a supplier or group of suppliers, a brand, or a program. Consumer loyalty is shaped by factors including familiarity with the brand, convenience, user experience, and perceived value [5]. Therefore, companies should assess whether the benefits of the program to be implemented actually affect customer.

2.1. Brand, store, and program loyalty

Consumer loyalty, i.e., repeat business, can be understood as the choice (preference or convenience) of a brand or a store or as the result of the company’s loyalty program. Analysis of three approaches to loyalty (to the brand, the store, and the program) will be conducted here.

2.1.1. Brand loyalty

Brands may either be offered exclusively by retailers or be available in a network of specific retailers; that is, a given brand cannot be purchased elsewhere. Brands can play a critical role in consumer loyalty behavior [6,7].

Four elements in particular influence brand loyalty: image of the store brand, confidence in the store brand, perception of the quality of the loyalty program, and cost of the program [6].

In their study of marine cruises [8] concluded that, although many vessels in the compared cruises are similar, the variables contributing to the perceived quality of service (e.g., facilities, organization, staff professionalism, and means of service delivery) influence the overall assessment of the ship’s brand. Thus, any improvement in the perceived variables influences the levels of satisfaction and confidence, and thus impacts brand loyalty.

Two important findings on brands. First, sensory experience is the primary engine of price and brand attachment, understood as a romantic short-term passion. Therefore, brand affection is the main mechanism promoting the development of behavioral loyalty, such as in purchases. Second, brand trust develops over the long run and is to be understood as attitudinal loyalty [9].

The brand appreciation of the brand is negatively related to brand penetration; that is, brand appreciation is lower for large brands and larger for smaller brands. This condition was tied to the brand life cycle; as the brand penetrates more markets, it must offer more benefits to attract different consumers rather than remaining with a specific niche of consumers. Consequently, the need to negotiate and form partnerships to achieve this goal arise [9].

The same author drew an important distinction between the brand appreciation and attitudes to the brand. Brand appreciation is a measure of brand potential in relation to the growth of behavioral loyalty. By contrast, brand attitude is a descriptive measure of the current state of a brand in relation to its brand. These distinctions may have importance for companies because brand appreciation measures can be used to predict brand trends in the medium and long term and to assess brand potential without being affected by size. When a larger company acquires a small brand, it can use mark appreciation measures to evaluate the potential for brand development. High brand appreciation, which results in the growth of behavioral fidelity, can balance the dilution of brand appreciation resulting from the need for expansion. However, measures of brand attitude can also be used to evaluate the current scope of the brand, even where this assessment is influenced by the size of the brand in the current situation [9].

2.1.2. Store loyalty

Some authors do argue that loyalty to the store should be measured by the intention to continue purchasing, but others suggest that spending volumes are a better indicator [10].

Those authors assert that the factors that most influence store loyalty are store appearance and environment, location convenience, store employees (a main motivating factor for store visits and confidence in the store), perception of merchandise quality, service quality, and social groupings (if customers at the same store share certain experiences).

Additionally, economic factors may influence store loyalty, such as pricing policies, costs of changing supplier, loyalty programs, and store promotions [11,12].

The development of store loyalty requires more than offering certain discounts through accumulation of points through purchases. A store loyalty program must have hedonic elements, and the judicious combination of these can turn cognitive satisfaction into affective love for the store, this may include the experience of driving a luxury car or watching an opera [13].

In an economic crisis, the benefits of a loyalty program can become financial savings.

2.1.3. Program loyalty

The fidelity to a program is part of an attitude of inclination toward the benefits and incentives offered by that program, which may result, directly or indirectly, in customer loyalty to the company [14]. This means that company loyalty can result from program loyalty. Loyalty programs can lead to distinct attitudes in relation to a program and to a company [15]. Program loyalty is associated with the economic considerations and is transactional, but loyalty to the company is emotional [16].

A study of new businesses entering the Chinese fuel market found that taxi drivers, whose work involved constant travel throughout a city, valued a loyalty program involving a larger network of partners, which facilitated the accumulation and redemption of program points at numerous locations. Thus, a loyalty program with more partners can be more attractive to consumers who value both economic benefits and convenience [17].

Consumers who are faithful to a loyalty program are sensitive to its financial advantages. Consumers loyal to the company value the experience of the transactions, and consumers faithful to the brand value the exclusivity of the product or service.

2.2. Loyalty program project

Loyalty programs can have different designs. They can be, for example, individual, coalition based, or clustered (this last is a new modality proposed in this study). Five important components make up program design: membership requirements, program structure, point structure, reward structure, and program communication. Section 4 details these. The five components are relevant to all types of program [18].

2.3. Benefits

Each program modality strategically determines the benefits and the rules for accumulation and redemption. Benefits are classified as utilitarian, hedonic, and symbolic [19].

Utilitarian benefits have tangible characteristics. They influence satisfaction, which results in greater confidence and program security [20,21]. Consumers recognize the utilitarian benefits of monetary savings or conveniences, and this can contribute to the repetition of the experience of buying a product or the frequent use of a service by a consumer.

Hedonic benefits allow consumers to explore new products or services from the redemption of points on purchases; these provoke sensations of pleasure and excitement. For example, the experience of driving a luxury car or watching the final game of a championship are considered hedonic benefits because they provide rare consumer experiences [19]. Contact with this type of benefit produces positive emotions and increases satisfaction with the program [22].

Symbolic benefits grant differential, preferential, or special treatment. These are extrinsic and intangible values accompanying a program. Consumers belonging to a group considered for differential treatment may increase their recognition of program members, increasing the affective state in relation to the program [23].

The variety of these benefits are critical to the success of the rewards program because they influence purchasing behaviors through their different perceptions, needs, convenience, and preferences.

3. Methodology

This study is exploratory. This type of work provides greater familiarity with a theme or problem and deepens preliminary concepts that had not been satisfactorily grounded or explored [24].

This study had two steps. First, bibliographical research was conducted to survey existing studies. Thus, theoretical publications can be used to explore an issue, problem, or theme, and this can be done independently or as part of a separate study [25]. A search in the Emerald, ScienceDirect, Scopus, and Springer databases identified relevant papers, of which 46 were selected for incorporation. After these were read in full, 33 were selected to be used for the theoretical foundation of this study. The most commonly used periodicals were: Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services (6), Journal of Business Research (3), Journal of Consumer Marketing (2), The International Review of Retail, Distribution and Consumer Research (2), Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science (2), Journal of Retailing (2), Marketing Letters (2), and Journal of Marketing.

The second step was to observe the functioning of the already consolidated modalities of loyalty programs (individual and coalition), comparing them with the new modality proposed here. To this end, we visited the largest center of textile production in Latin America, located in Blumenau, Santa Catarina, Brazil, and we identified the main forms of benefits offered to customers by the corporations headquartered there. The following variables for each program: partner participation, benefit accumulation, options for redemption, market range, program management, and program goal.

The following hypotheses were created to orient the study:

H1. The literature identifies two program modes in loyalty programs (individual and coalition) as the most common. The analysis of the characteristics of these two categories allowed the proposal of a new type of program, called cluster mode. We believe that this type of program has never been described in the literature.

H2. A loyalty program can be directed to brand loyalty, store loyalty, or program loyalty.

H3. The individual mode is better suited for companies seeking to create and sustain brand loyalty.

H4. The coalition mode is better suited to companies seeking program loyalty.

H5. The cluster mode is better suited to companies seeking store loyalty.

The validity of the hypotheses are examined in this study.

4. Program modalities and proposal of a new mode

Loyalty programs must select a mode before being implemented. This choice should be made with reference to, for example, the intended objectives of the program [26]

The theoretical support located for this paper indicates two prevalent program modes: the individual mode and the coalition mode. In this study, a new modality will be presented, called the cluster mode for loyalty programs.

4.1. Individual program modality

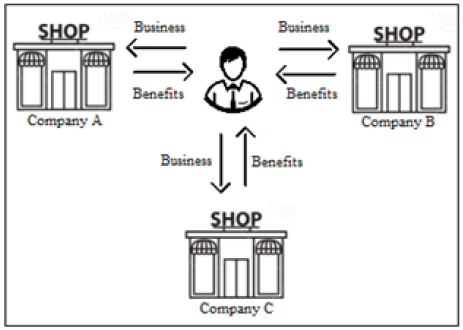

In this mode, program benefits (points or bonus) are accumulated through the company and subsequently redeemed there. The use and acquisition of tangible goods or services of a given company allow consumers to accumulate benefits, which are then redeemed as goods or services of that same company, either discounted or free. This mode is widely used by airlines and programs using it are often referred to as frequent-flyer programs [1]. Fig. 1 shows how benefits are accumulated and redeemed.

Adherence to the individual modality is associated with the type of benefit that the company offers. If the company offers, for example, benefits as points, the consumer should have retain records of their transactions or their accumulation of points. If the benefits are in the form of stamps, vouchers or labels (among others), the consumer will manage the benefits without having to be enrolled in the program. A points structure thus incorporates an immediate relationship between acquisition and redemption.

Because the program is operated by the company itself, its structure of the program is relatively simple, and it can be managed in two ways: administration by the company (generally large companies) or by the consumer (such as with stamp accumulation, vouchers, or labels for a given product).

In this mode, benefits are accumulated only within a single company.

The benefit structure usually involves discounts, gratuities, bonuses, and/or points. The client only has access to the accumulated benefits if they perform new transactions with the company offering the loyalty program, which is the only one that allows the redemption of benefits [27].

In the individual mode, program communications reach only active consumers. Its scope is limited to the company’s current market ranges, reducing the ability to attract new customers through the program.

4.2. Coalition program modality

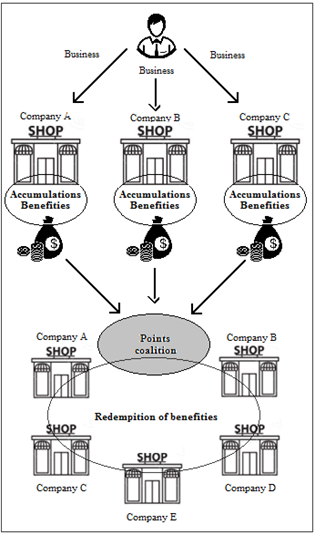

In this mode, the accumulation and redemption of benefits can take place in different companies, who are referred to as partners. Thus, a consumer with accumulated benefits from frequent use of a credit card can redeem its benefits as airline miles or as other products in a network of associated companies. Here, consumer loyalty is not limited to single establishment but can be used in a network of trading partners. Fig. 2 illustrates the dynamics of accumulation and redemption of benefits in a coalition.

Within a coalition modality, the consumer is recorded in the program (having formal membership), enabling the company to better understand the needs, preferences, and convenience of its customers and other network consumers. The program structure of the coalition allows for strategic advantages regarding network maintenance costs and for the benefit of the positive image effects of partners while maximizing cross-selling opportunities [28].

Thus, the coalition structure is larger and well defined, composed of a wide and varied network of partners. In such a mode, the consumer can obtain points in a wide, varied network of participants. A company that offers benefits through a coalition loyalty program will likely sell its product before its competitors with no program or another modality of program [29]. This leads to consumer loyalty to the loyalty program itself rather than to the service provider or retailer [30]. The dynamics of the coalition mode requires structured benefits in the form of points or in the program’s own currency, which facilitates transactions with network partners.

Coalition loyalty programs form partnerships as alliances with other companies to create and strengthen the relationships with the existing customer base. This is done by promoting direct sales to those customers, offering them the opportunity to accumulate points over time by doing business with the partner companies [31].

Program communication includes the consumers of other markets; that is, the company can reach consumers from other segments, allowing the opening of a new channel of brand publicity and the realization of joint promotional actions with other partners. Consequently, program costs are smaller because the number of customers attracted, their rate of participation, and the potential for cross-selling between partners increases [32]. A main goal of coalition loyalty programs is to promote greater volumes of information (insights) into consumer preferences and behaviors [33], relative to other existing forms of relationship.

Coalition programs can also appear in another configuration, in which a new company centralizes the management of benefits. That is, a new company, which does not directly offer products or services, is created solely to manage the program. The function of such a company is to bring together several companies from different industries that provide benefits to consumers in business transactions and to accept rewards points in transactions with consumers. In this way, consumers can have access to a vast network of diverse suppliers for the redemption of benefits. Examples of such companies are the Nectar program in the UK and the DOTZ program in Brazil.

The Nectar program is the UK's largest loyalty program, with 16 million program participants and over 500 brands for customers to collect and redeem points [34].

Created in Brazil in the year 2000, the DOTZ program became the largest loyalty program in the country in terms of number of participants. The highlight of the company's trajectory was when the Canadian company LoyaltyOne acquired 31% of the company in 2009 and diversified its operations in other market segments. At the end of 2016, Dotz accounted for 22 million registrations, 10 thousand daily redemptions in products and services and about 900 distributed points per second. The company's main focus is on retail sales, and consumers rely on a diverse network of companies to accumulate and redeem points, such as supermarket chains, clothing stores, gas stations and pharmacies, as well as network of telephony services [35].

4.3. Cluster program modality

A cluster is an association of organizations operating within one business area, generally seeking to reduce supplier costs and to encourage the social and economic development of the region in which the cluster exists.

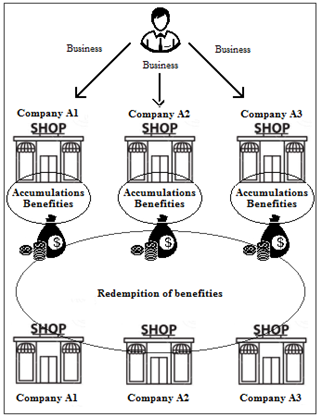

A customer loyalty program is considered a cluster if it includes companies from one branch of business that act in an associative way to offer their customers benefits that stem from the repetition of business. Fig. 3 illustrates the dynamics of the accumulation and redemption of benefits in a cluster. The structure of the program, therefore, involves consumer action in companies that operate in a single branch of business.

Cluster loyalty can be found in the commercial pools of the clothing sector, formed by organizations from a single segment that associate to verticalize loyalty, such as the aggregation in a commercial shopping center of garments of different seasons, children's fashion, adult, beds, tables, bath products, and others.

As in the coalition modality, the cluster modality exhibits a need for enrollment into the program (formal membership), allowing the possibility of reaching the customers of other consortium members, increasing the sphere of potential business.

The participation of consortium members in concession and redemption of benefits presupposes a partial integration of operations; that is, the companies interact with each other.

Similarities exist between the coalition and the cluster modalities. However, these are modalities with distinct characteristics. In a coalition, the participating companies operate in different branches of business, offering different goods or services, such as credit administration, pharmaceuticals, groceries, furniture, and air travel. In a cluster, the participating companies operate in different segments of the same business, similar to a commercial manufacturing center, where enterprises may offer items related bed or bathing needs.

Benefits may be structured such that in a coalition modality, the benefits granted are converted into points from a proprietary currency, whereas in the cluster mode, benefits, instead of being converted into points, are generally granted in the form of bonuses, giveaways, discounts, awards, or bonuses.

In the cluster mode, the communication of the program reaches the same market bands, diversifying itself in offers of products for different segments. Thus, potential expansion of the consumer base is greater than the individual modality.

The point structure is restricted and cumulative, and it includes all companies in a given cluster without, however, altering the consumer market.

4.4. Comparisons of program modalities

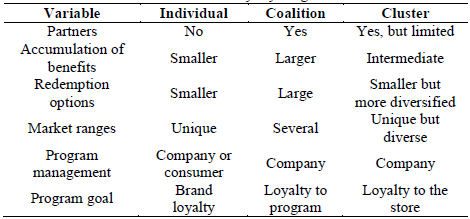

The studies drawn from the literature and our empirical observations allow us to compare certain variables regarding individual program, coalition, and cluster programs. Table 1 highlights the behavior of these variables for each mode.

4.4.1. Partners

The main characteristic of partners in the individual modality is their absence; that is, the company operates the entire loyalty program alone.

The main managerial implications of the individual modality are that all costs of the program are absorbed by the company, and the scope of the program is limited to the customer base of the company customer base, in the same market ranges.

Some practical case studies in this mode include investigations of certain airlines’ programs, perfumery shops, and supermarkets. No other suppliers participate in this version.

The advantages of the individual mode include its adaptability and flexibility, ease of operation, and restriction of redemption to tangible goods or services from the company itself, requiring consumers to perform further transactions with the organization to take advantage of their benefits.

4.4.2. Accumulation of benefits

Consumers can accumulate more benefits in the coalition modality, with the cluster modality featuring fewer benefits, and the least being available through the individual modality. Examination of credit card coalition programs, fuel supply networks, specialty product shops, and similar types of programs is fruitful here.

The managerial implications include the integration for operationalization of a program (for example, information from a variety of sources can be made available to each participating company) and a wide and varied network of partners.

4.4.3. Redemption of benefits

Wide and varied coalition partner networks facilitate the accumulation and recovery of benefits in relation to the individual and cluster modalities. In the coalition mode, the company allows customers of other companies to redeem goods or services using points accumulated from other participants in the program. This means that management actions require the full integration of operations of the accumulation and redemption of benefits with other program partners.

The possibility of reaching a customer base that can be developed is a particular advantage. A case study of this situation is to be found in credit card operators whose consumers accumulate points using the service and as well as the amount spent on a fuel supplier, for example. After the accumulation of points from these two companies, the user exchanges the points for car rental at a company that is new to that user. As a result of this transaction, the vehicle rental company acquires customer access to the partners of the coalition program, which represents an opportunity to expand its customer base.

4.4.4. Market ranges

The individual modality does not allow the given company to diversify into new market segments; that is, the program only reaches existing consumers. In the cluster mode, the scope of the market is also limited, but the performance is more diverse. A cluster loyalty program in footwear can reach purchasers of children’s, women’s, and men’s shoes, as well as consumers of specialized (e.g., sports) shoes. In the coalition mode, a large and varied network of clients is available, including those from other regions and even from other countries. This example of the previous section shows how the customer base of other companies can be accessed.

4.4.5. Program management

In the individual mode, program management is performed by the company itself or by the consumer. In the latter case, benefits take the form of accumulations of stamps, vouchers, or labels for a given product. For instance, a customer may accumulate 10 labels for a particular brand of pizza and can redeem them for another pizza.

In cluster mode, other companies take part in a concession and take part in redemption, which determines the need for a program management model that integrates information from multiple sources and is centralized in each participating company. This generates important managerial implications.

For example, a supplier of children’s clothing can, through this modality, acquire access to a consumer base of clothing for adults or of sports clothing.

The management of such a program can be done in one of two ways: management of each participating undertaking or by a company created to manage the various partners associated with the program. In this second case, the program is not the same as the company itself, but it is associated with the program and hence directly to other partners. The DOTZ and the Nectar programs in Brazil and the UK, respectively, include companies that specialize in the management of coalition loyalty programs.

4.4.6. Loyalty approach for each modality program

By opting for a modality program, a company can direct efforts to achieve a specific type of loyalty; in other words, it must define what approach it desires.

The dynamics of the accumulation and redemption of benefits, performance in a given market, program management, and partner non-participation are features of an individual modality that allow a company to emphasize brand loyalty in a loyalty program. Program actions must be aligned to this purpose, including the definition of benefits, form of accumulation, and validity of the benefits. The goal of this modality is to acquire repeat business with the brand, as consumers must continue transacting with it to redeem their accumulated benefits. For example, a pizzeria that deploys a program in the individual mode will only allow its benefits to be redeemed in its own products rather than offering products of another enterprise as redemption options.

A loyalty program in the coalition modality is an alternative to allow companies to promote loyalty to the program. The participation of partners in the accumulation and redemption of benefits are characteristics that highlight the focus on utilitarian benefits; that is, consumers are motivated to join the program and continue with the given businesses mainly for the value of the benefits. Thus, all efforts should be directed to allowing further accumulation and redemption of benefits in a wider and more varied network of partners. The possibility of exchanging points with another partner program for products or services is an opportunity to access customers of other segments, who may then become consumers of the company.

The cluster program is most suited to companies that are seeking store loyalty. Consumers can accumulate and redeem their benefits with a set of associated suppliers. All actions should be aligned with this purpose; that is, the program should attempt to attract and retain loyal customers of suppliers associated with the cluster. For example, consumers loyal to a shopping mall clothing company can accrue benefits at a clothing store for adults but redeem them in a clothing stores specializing in children.

5. Conclusions

This study contributes to the literature on rewards program in its logical, practical presentation of the modalities of loyalty programs and their principal characteristics and the dynamics of accumulation and redemption of benefits; forms of management of such programs; the nature of rewards benefits; the market ranges covered; and the main focus of the program. In addition, a new modality of loyalty programs is proposed here. The management implications for each modality are analyzed, which helps contribute to the advancement of knowledge in the area and enables improvements in business practices.

In the literature, there have been a variety of studies on program modalities and the impact of programs in various scenarios. However, existing work tends to prioritize the individual and coalition modalities, restricting the most usual practices of loyalty to these two. An extended and objective analysis, including alternative program modalities, would certainly facilitate understanding for readers and would arouse business interest in using this practice of consumer relations.

The hypotheses created to guide this study are revisited in light of the above analysis.

In addition to the modalities usually presented in the literature (individual and coalition), this study presents a new modality of loyalty program, termed cluster. The dynamics of running a cluster rewards program, that is, its performance as an associative form, are exhibited in a new type of program (H1).

It is observed that each modality is accompanied by efforts for a specific loyalty approach, with managerial consequences and distinct results (H2).

Individual modalities are more adequate for companies that seek brand loyalty. The benefits are accrued for branded transactions, and redemption is conditioned on the conduct of future transactions, making it necessary for customers to negotiate with companies to transform benefits into values (H3).

The coalition modality is most suited for companies seeking loyalty to the program. In this condition, the company management seeks to gather the largest number of partners to act in various segments of market, offering wide networks for the accumulation and redemption of benefits.

Such benefits can be redeemed within a partner network, either at the initial provider or another provider in the network. The coalition modality does not restrict redemption at a single supplier, but within network partners (H4).

The cluster modality is more suitable for companies seeking store loyalty. In this modality, loyalty is conditioned to cluster stores; that is, the consumer can transform their benefits into value in the set of stores and not necessarily at the same store. For example, a consumer may purchase products at a children’s clothing store and redeem the associated benefits at an adult clothing store (H5).

Future studies of the positive impact of benefits on store loyalty and the influence of cluster modality have a multiplying effect, contributing to the expansion of the frontiers of knowledge of customer loyalty programs.