1. Introduction

Project management is linked to the most ancient man practices, since the construction of the Egyptian pyramids, which has demonstrated the ability to initiate and complete complex projects [1] and work in teams. Project teams have been defined as a group of people with complementary and transdisciplinary skills [2], with different knowledge and experience, on the other hand, working collaboratively to achieve a shared goal more effectively than working individually [3] and it plays an important role in the success or failure of the project [4].

Some of the challenges that the literature has recognized in project team management can be classified as external and internal. Externally, the work is developed in a context with high levels of uncertainty [5] and great time pressures [2]. Internally, which are mainly associated with the changes that the team may have at different stages of the project life cycle, that makes training processes difficult [6] and the need to develop capabilities through continuous interactions among its members [7]. Therefore, these teams are likely to work under a high degree of stress and interpersonal demands, which generally decrease their performance [8].

In the field of renewable energy project-based organizations, currently their most important challenge is low project performance and although the literature has sought to establish different critical success factors, only a few empirical studies have addressed this issue, specifically in projects within this field [4].

Under this scenario and given the global dynamics of energy transition (ET), these challenges are of strategical importance, since they require articulating the work of interdisciplinary teams and processes aimed at achieving environmental, economic, and social sustainability [9]. In addition to this, a project of this nature implies institutional, technological, organizational, and political changes; therefore, its effective development requires the identification and adequate management of the human capital involved from the beginning, either as a member of the team or as a stakeholder [10].

Consequently, this paper aims to reflect on the critical success factors and barriers that, from the perspective of experts in the Colombian mining-energy sector, are identified in the management of ET project teams. To fulfill this purpose, a focus group methodology is used, guided by a set of previously designed questions, which is considered appropriate, given the exploratory scope of this work.

The results have theoretical and practical implications. From the theoretical point of view, this study is, based on the authors' literature review, the first to address these topics in the Colombian context and, therefore, it is a reference for future research. At a practical level, the findings can be a guide for energy transition project managers to define courses of action that will allow them to better manage their teams and, therefore, the project.

To fulfill these purposes, the document is structured in four sections. The first one develops the concepts of project team management and the energy transition process; the second one presents the theoretical elements of the focus group methodology; the third one compiles the main findings and the discussion of results; and finally, the fourth one presents the conclusions of the study.

2. Reference framework

As it has been mentioned above, addressing the challenges of managing energy transition or renewable energy project teams constitutes a research opportunity. Under this rationale, this paper addresses two main aspects, namely: first, the construct of project team management, highlighting critical success factors and barriers; and second, the concept of energy transition and its implications for project management.

2.1. Project team management

The concept of project teams is initially established from the definition of its terms: team and project. A team is defined as "a small number of people with complementary skills who are committed to a common purpose, a set of performance objectives and an approach for which they hold each other accountable"[11].

As a matter of fact, from the perspective of the Project Management Institute (PMI), a project is a system of interdependent and interacting activity domains, both among its parts and with external systems, which causes permanent changes that require special attention and timely response to achieve positive performance [3].

In this way, project teams carry out defined, specialized and time-limited activities, in other words, with a duration conditioned to that of the project [12]. This can mean changes in the workload, uncertain requirements and demands on multiple functions, which can generate, among other risks, additional pressures on the employee and, therefore, problems for their well-being and ethical treatment [13].

Some of the characteristics that have been recognized by project teams are associated with their composition, in this way, characteristics of the personnel that make them up, highlighting what that they may belong to different departments of the organization, contexts, and industries. Likewise, the tasks involve specialized knowledge, experiences, and skills of its members that, in some cases, allow qualifying the project team as multifunctional; with contradictory findings, reported in the literature, all about its benefits [14].

Therefore, in project management, team development acquires relevance, tending to strengthen generic aspects, such as: awareness of the vision and objectives of the project; understanding and fulfillment of their roles and responsibilities; communication and problem solving to reach consensus; orientation and collaborative work to promote group growth, among others [3]. Thus, project teams and their decision-making processes, operations, administrative processes, experiences, skills, and tools must be managed to improve the probability of project success [15].

2.2. Critical factors in project team management

Critical success factors (CSF) first mentioned by [16], are defined as characteristics, conditions or variables that can have a significant direct or indirect impact on project success and, therefore, must be sustainable and properly managed [17,18].

In the specific case of renewable energy projects, previous studies allow classifying CSFs into communication, equipment, technical and environmental factors [1,19]. Although, with this classification the importance of different aspects is recognized, the project team constitutes the backbone, because its execution is not possible without them [4], even more so when there are new challenges, since the teams are acquiring a universal scope, due to the lack of trained employees in a particular country [1].

Table 1 Critical success factors in project team management.

| Critical factors of success | Definition | References |

|---|---|---|

| Leadership | Ability of the team leader to influence the team towards achieving the objectives. | [20] |

| Senior management support Project team coordination | Effort provided by senior management to assist the project team. | [20] |

| Rewards and sanctions | What the organization gives in exchange for good work (salaries or bonuses). | [20, 21] |

| Skills and knowledge Capacity/competence of the team | Knowledge, experience, and ability of team members to process, interpret, manipulate, and use information. | [1, 4, 20, 21] |

| Functional diversity Appropriate selection of the project team | Appropriate selection and differences in functional roles. | [1, 20] |

| Clarity of goals and objectives | Degree to which project goals are well defined and communicated. | [20, 21] |

| Cooperation | Establishes how well team members work with each other and with other groups. | [20] |

| Communication | Exchange of knowledge and information internally or externally. | [20] |

| Learning activities | Process of taking action, feedback, and improvement. Team self-learning | [4, 20, 21] |

| Cohesion Teamwork | Spirit of togetherness, support, and trust among team members. | [1, 20, 21] |

| Effort Team empowerment | Degree to which team members are willing to work hard on the project. | [20] |

| Compromise | Emotional or intellectual attachment of team members to the project. | [1, 20] |

| Task orientation | The project team's knowledge is integrated with the project task. | [1, 4] |

Source: Own elaboration from reference documents.

From the focus of this paper, Table 1. presents a compilation of CSFs in project team management, which are applicable for energy transition or renewable energy projects.

2.3. Project team management barriers

The literature has also documented different cross-cutting barriers to the management of renewable energy projects; the study [5] reports four, namely: regulatory, technical, economic, and technological development barriers. In turn, [22] are presented economic, institutional, technical, and sociocultural barriers that prevent countries from moving from high to low emissions pathways. Likewise, studies [23], [24] express concern about technical standards and economic regulation and point out the importance of consulting and respecting the institutional framework.

Regarding barriers, different aspects have been reported in the literature that may explain why project team management is not effectively practiced; some of these are presented in Table 2.

Table 2 Barriers in the development of energy transition and renewable energy projects.

| Barrier | Description |

|---|---|

| Lack of authority | In some cases, organizational structures generate that team members do not receive direct supervision from project managers, but from their supervisor. In addition, in functional and matrix organizations, most project managers do not have authority in many areas of team development, such as reward and training, as these are traditionally the purview of a functional manager. |

| Availability of team members | Unlike other organizational teams, a project team member can be involved in several projects at the same time. |

| Heterogeneous teams | Most project teams involve members from different disciplines, which can make it more difficult to build cohesion. |

| Timing of project manager assignment | In some cases, a project manager is assigned only when the project has already started, and therefore the project manager is forced into urgent planning and execution, leaving no time for team development activities. |

| Work-oriented project managers | In many organizations, project managers are assigned according to their technical competencies. As a result, many project managers are work-oriented, rather than people-oriented, and consequently, the soft skills needed for team development lag behind. |

| Particular characteristics of a project | The results of team development management are not immediate, whereas a project is a temporary, time-limited effort. Therefore, the positive effects of the team development effort may not manifest themselves at the end of the project. In addition, these are unique in nature, so the results of team development practices cannot be generalized. This suggests that unique project team development practices should be identified that are cross-cutting to others of different focus and duration. |

Source: Own elaboration, data taken from literature from Zwikael, and Unger-Aviram, 2010.

Energy transition and its implications for project management

Energy is essential for all human beings, so its supply must always be available and affordable and at the same time protect the environment and climate for future generations. Therefore, it is necessary to refer to the term energy transition, of which, although there is no widely recognized meaning, complementary definitions are reported in the literature.

According to [25,26] energy transitions are continuously developing processes that gradually change the composition of primary energy supply sources. Likewise, in [27] an energy transition can be defined as a significant change in the energy system of a country, a region, or even at the global level; a change that can be associated with the structure of the system, the energy resources used, their costs, or even the political-economic regime in which energy supply and consumption take place. Likewise, this author [27] states that throughout history, there have been many energy transitions; and in the same way, in [28], these are linked to industrial revolutions, given their productive transformation processes and their widely known disruptive advances.

Regarding the current energy transition, in [29] it is defined as the process of change or transition from primary energy sources such as oil, coal and natural gas to clean energy sources such as wind, solar or geothermal. In contrast to this definition, [30] mentions that what has really happened is that the new energy sources have been added to the existing traditional ones, and therefore have never replaced them.

Based on the above, it is established that the energy transition is the result of evolutionary developments and technological advances experienced by humanity for the provision of energy, which involve multiple processes of change with effects, positive or negative, in various areas such as the economy, politics, the environment, among many others. An example of this is the current climate conditions faced globally, which have required each country to draw its own energy transition roadmap, in which the individual goals defined in the 2030-2050 global agenda are articulated with their own potentialities and limitations.

It is important to mention that roadmaps, for each country, generate diverse challenges, including project management which demand multidisciplinary work to align, negotiate and pursue broad and fair objectives, beyond those specific to a project [31]. This implies a framework for the responsible management of energy transition projects, which contemplates particular needs, ranging from working with communities, especially those reluctant to change, on conservation issues such as land availability, landscapes and impacts on species and habitats [32]; to managing issues related to modernization and digitization [33] that link modifications in the traditional ways of developing business and operational processes in the different segments of the energy supply chain.

3. Materials and methods

As a result of the review, it is considered that this is the first study that explores the CSFs and barriers in the management of project teams oriented to energy transition in the Colombian context. Therefore, the focus group technique is considered appropriate to collect primary data on the perceptions and experiences of experts [34], on the factors that drive or hinder team management in projects of this nature.

Focus groups are defined in [35] as "an informal discussion among selected individuals, on specific topics", similarly in [36] it is stated as "a discussion group, guided by a set of carefully designed questions with a particular objective"; its implementation is not restricted to a particular context or area, so it is considered a methodology of generalized usage. Its intention is the group interaction that allows access to knowledge provided within a natural behavior, resulting from their experiences, practices, expressions, censures, replicas, and contributions [37], distinguished then by a qualitative approach of propositional cut [38].

Concerning to the profile and number of participants, the recommendations given in [39] are followed, so that they are homogeneous in the level of knowledge and experience in the mining-energy sector, and in [34,36] with a total of five experts, complying with the range of several no less than three and no more than twelve.

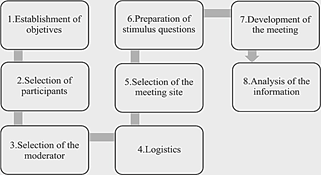

Source: Own elaboration based on: Escobar, Francy, and Bonilla-Jimenez, 2017.

Figure 1 Stages of the focus group.

According to the stages suggested in [36] this study adopts eight, namely: 1. establishment of objectives, 2. selection of participants, 3. selection of the moderator, 4. preparation of stimulus questions, 5. selection of the meeting site, 6. logistics, 7. development of the meeting, 8. analysis of the information, which can be visualized in Fig. 1.

The discussion of the focal groups generally produces qualitative and observational data where analyses can be demanding [38]. In this case, a two-stage data coding is chosen, the first one is an initial coding in which the emerging ideas are listed and the keywords used by the experts are identified according to the frequency of occurrence; the second one is a focused on coding, where the most recurrent ideas around each question are punctuated and categories are established [38] for each of the findings.

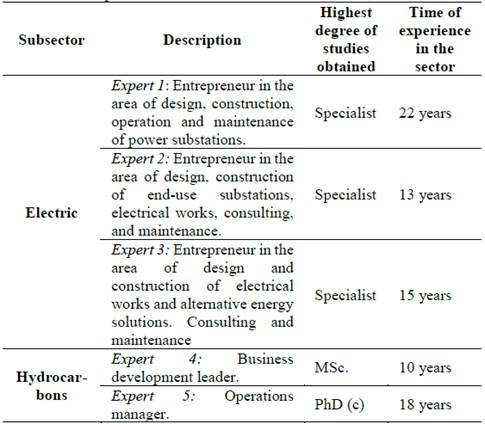

3.1. Profile of participants

The experts participating in the focus group are listed in Table 3. indicating as relevant aspects their current position and work experience. In addition, their links in two subsectors, which are electricity and hydrocarbons, both are highlighted.

3.2. Focus group guiding question

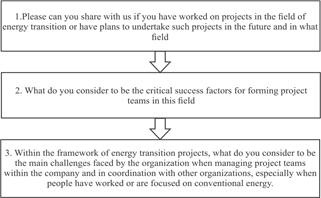

The guiding questions or also called stimulus questions [36], are those that encourage conversation, which should preferably be casual without the need to adhere to a format or structure, so that it is a pleasant and natural interaction.

The questions used in the focus group are shown in Fig. 2.

4. Results and discussion

The data analysis starts from the guiding questions of the focus group, initially identifying the emerging ideas and the most recurrent terms in the experts' discourse. From this point of view, key aspects are identified, and broader arguments are developed.

4.1. Experiences in energy transition or renewable energy projects

The participants report their experience in this type of projects, highlighting the following aspects:

Growth and consolidation of ventures driven from the energy transition, with initiatives based on the implementation of solar panels, which constitute attractive projects with tax benefits (expert 1).

Development of energy efficiency projects at the industrial level. In addition, it plans to work on photovoltaic and wind energy solutions for its clients at the end-use level (expert 2).

The company for which he currently works, is developing a project with Ecopetrol to carry out exploratory drilling to enable the possible use of white hydrogen, a resource that, in the medium and long term, is expected to drive the energy transition (expert 3).

Energization of the photovoltaic plant "El paso solar", the largest in Colombia, a project led by the Enel Green Power organization; also, in support for the supervision and control of wind power generation plants in La Guajira (expert 4).

Municipality of Florida in Valle del Cauca; and solar thermal energy in condominium housing units in different parts of Colombia (expert 5).

Despite the reported experience, it is clear how these change processes also generate uncertainties, not only for the organizations but also at a personal level, as expert 1 pointed out:

Although, I am fearful and uncertain about the arrival of the energy transition, with my background as a petroleum engineer, I am supporting projects of this nature for the company's customers, given the new demands and expectations regarding the use of clean energy resources.

Likewise, the institutional efforts made in this process are highlighted, according to expert 2, these correspond to:

From the Colombian Chamber of Energy (CCE, called-Cámara Colombiana de la Energía, Bogotá-Región), we have been working very hard to promote the energy transition, an example of this are the efforts made around electric mobility and mentoring with institutions that offer careers in the area of electricity, to close gaps in the training of human talent, as a "cannibalization" is identified among companies for skilled labor in these areas of training.

4.2. Critical success factors in the management of energy transition or renewable energy project teams

Table 4. summarizes the critical success factors prioritized by the participants and classifies them according to the categories defined in the literature. As a result of the analysis, a new category emerges, called articulation with the environment, which is characterized, on the one hand, by stimulating processes of creation, innovation, and access to modern technologies to mitigate the backwardness of these issues at the national level; and on the other hand, by fostering collaborative and trusting environments for the formation of project team networks.

4.3. Barriers to the management of energy transition or renewable energy projects

The barriers identified by the participants are presented in Table 5. highlighting that they are of an economic, institutional, technological, and social nature, which coincides with what has been documented in the literature [32,33,40,41].

In the context of project teams, there is consensus on three specific aspects that constitute barriers to effective management:

Lack of training and experience of team members to present energy transition projects, which leads to some calls for proposals being declared as deserted.

Difficulty for organizations to retain human talent with high levels of specialization, which in many cases leads to unfair competition to generate personnel mobility among companies.

Lack of articulation and teamwork, at inter and intra-organizational level, to develop energy transition projects and that, to a large extent, is due to the lack of vision of senior management to bet on the issue of sustainability.

Table 4 Critical success factors in energy transition projects

| Critical success factors | Characteristics |

|---|---|

| Leadership | All agree on the need for effective leadership within the organization, headed by a manager and project team, with high management skills that assigns roles and responsibilities and integrates his team horizontally. |

| Senior management support Project team coordination | There is consensus that senior management must create a common vision and align personal and organizational perspectives as a strategy to mitigate high staff turnover. |

| Skills and knowledge Team capacity/competence | Three experts mention that human capital is fundamental, and therefore refer that companies should not limit their efforts in recruiting personnel with a mix of academic preparation, experience and attitude, and in the same way, one of them points out that they should strive to advance processes to update skills at all levels of the organization. |

| Clarity of goals and objectives | The definition of clear objectives within the framework of the energy transition, but even more so the creation of a shared vision that commits all members of the organization, especially those who have significant experience in conventional energy projects, is emphasized. |

| Cooperation | Two experts agree in mentioning that this type of project has multiple stakeholders, which must be managed, based on their needs and expectations, since they are involved in the different stages of the value chain. Thus, it is necessary to generate cooperation not only within the project team but also with the stakeholders with whom they interact. |

| Communication | Two experts identify communication as a critical success factor, since its good management depends on achieving a good organizational climate, which is fundamental in the management of projects of any nature, and even more so in energy transition projects, which are new for many companies. In this sense, they highlight internal communication, to coordinate the execution of activities; and external, with communities and other stakeholders to mitigate potential risks. |

| Learning activities | An expert indicates that, within organizations, significant resources should be allocated for training on the issue of energy transition. This will allow the handling of transversal and reliable concepts for all those who will formulate or develop this type of projects. |

| Effort Team empowerment | Given that this is an emerging topic that many organizations are exploring, a key element of the project team is that its members have the willingness and commitment to document lessons learned, supported by the design of tools such as: protocols, flowcharts, and contingency plans (dynamic and feasible), which promote the success of the projects. |

| Compromise | It is necessary to design policies to increase the level of employee commitment, since there is a high turnover of personnel in this type of project. |

| Task oriented | Four of the five experts in the focus group highlighted the financial issue and the leverage that this resource represents for the development of projects of this nature. In this sense, it is necessary for the project teams to have qualified personnel in the formulation and management of projects, in order to apply for different national and international calls for proposals. |

| Articulation with the environment | All the experts identified the importance of the project team being adapted to the digital transformation, to the acquisition of new technologies and to environmental sustainability. One of them suggests establishing national and international "energy clusters" in which collaboration and trust networks are generated between teams in the mining-energy sector, since the mastery of multiple solutions and technologies required by energy transition projects is still incipient in Colombia. |

Source: Own elaboration, based on a focus group with experts.

Table 5 Barriers in energy transition and renewable energy projects

| Barrier | Characteristics |

|---|---|

| Economic | A clear policy is required for energy transition projects to achieve true sustainability, i.e., to be framed by environmental, social, and economic objectives. |

| Institutional | Lack of linkage, as strategic partners, or allies, of the institutions that lead conventional energies, and that have extensive experience providing energy historically. An example of this is the oil industry, which can be shown the real objectives of energy transition projects. The gaps between traditional and sustainable energy transition projects, which are accentuated by the geopolitical context. Excessive procedures in the calls for energy transition projects and the lack of training of organizations to apply for them, which often lead to these calls being declared void. |

| Technology | National lag in research, innovation, development, or effective adoption of applied and relevant technologies for energy transition projects. |

| Social | Biases and resistance to change on the part of communities and other stakeholders. The supply of the educational system, which has not reached the required levels of sufficiency and relevance. An example of this is the field of wind power generation, where specialized personnel are brought in from other countries to develop the projects. |

Source: Own elaboration based on a focus group with experts.

5. Conclusions

In the current context characterized by a growing awareness of environmental care and the importance of ensuring energy security, projects oriented to energy transition and renewable energies are becoming increasingly important for society. However, within the framework of these projects, different studies have addressed their critical success factors (CSF) and barriers, which include team management as a central aspect, given their particular characteristics such as trans-disciplinarity, heterogeneity, high uncertainty environments, among others, which are accentuated by the universal scope of these teams, given the shortage of trained personnel in some countries.

In accordance with previous findings reported in the literature, in this study the experts also agree that the CSFs in the management of ET teams are oriented to leadership, top management support, cooperation, communication, learning activities and commitment. In addition to the above, this work identifies an additional category of CSF called by the authors "articulation with the environment", which, according to the experts, includes the most important variables to manage to achieve positive results in ET projects, namely: digital transformation, the creation of collaborative networks and trust in the sector, and the allocation of financial resources.

In this sense, and in order to achieve development paths for the energy transition, it is important to highlight that, at the national level, strategic alliances should be made with organizations, associations and institutions that lead conventional energies, since they can leverage this type of projects, taking advantage of their knowledge, skills and financial strengths, to help diversify, to a greater extent, the national energy matrix.

With respect to barriers, it should be noted that the academy and the sector must agree on specific knowledge, skills, and abilities to be developed in human capital, in such a way that they respond to the needs and demands of ET projects. Likewise, organizations should strive to design policies and programs that lead to the permanence of specialized personnel as a valuable capital of the organization, as a way to mitigate the high personnel turnover, and the aggressive competition to attract people from other organizations once they have reached a level of maturity in their learning curve.

Likewise, sustainability thinking must be integrated into the activities of the supply chains of the electricity sector processes (generation, transmission, distribution, and commercialization), including product design, material selection, manufacturing or service provision, storage, use and proper disposal at the end of the product's useful life. In this way, true sustainability can be achieved in ET projects, integrating the responsibility of all parties involved.

Finally, this study highlights the academic and business importance of project team management and recognizes that there is a lack of consensus on how to define its success and what factors contribute most to this outcome. Therefore, it is suggested as a future avenue of research, to advance in this area for organizations to better manage project team performance [20], which includes managing their critical success factors and associated barriers.