INTRODUCTION

Although by 1848 an attempt to make reports of suspicion of adverse drug reactions (ADR) had already been made due to the death of a young woman by the administration of chloroform during surgery in England [1], it was only until 1960s that the first pharmacovigilance (PV) systems were originated as a result of the phocomelia outbreak caused by the administration of thalidomide [2]. After this episode, a series of articles have been published evidencing the harm caused by drugs: Talley's study published in 1974 identified that 2.9% of admissions to the health service were for this reason and that 6.2% of the patients died [3].

Subsequently, Manasse published in 1989 a couple of articles where he states that, in 1987, drugs mortality affected 12 thousand Americans and morbidity reached to 15 thousand hospitalizations. He also coined the expression Drug Misadventuring to describe negative drug experiences that he considered a problem of public policy derived from the excessive use of drugs and error-prone preparation and distribution systems [4, 5]. Lazarou et al., in 1998, identified that the incidence of serious and fatal ADR in hospitals in United Stated was extremely high [6].

According to the current definition of the World Health Organization (WHO), the PV is concerned with the identification, evaluation and prevention of adverse events and drug related problems, as a result of the use of these [7]. By 2012 the national pharmacovigilance program in Colombia considered that PV should study the problems related to the use and effects of the use of drugs in society with the aim of preventing and solving them [8, 9]. Today, regulatory agencies work to balance free access to drugs with safety concerns, in line with their mission to protect the public heath advancement [10].

Not only ADR are part of the daily concerns of health professionals, there is also an interest in others risks of health care, such as nosocomial infections, complications of the clinical course and medication errors. From 1955 the sanitary and economic consequences of these risks were evident, which Moser a year later called "diseases of the progress of medicine". After these dates, there have been several studies where it is estimated that between 4% and 17% of adverse events occur in hospitals, of which approximately half were considered avoidable [11].

The document To err is human identified that about 98,000 people die in a year due to errors in health care that occur in hospitals. After this document, the WHO in 2004 pointed out to the governments of the world the need to establish programs that guarantee safe actions in the care of the patient in the hospital setting and suggested a global strategy to fulfill this purpose [12, 13]. Colombia has not been unaware of this situation and through the Ministry of Social Protection urges institutions to implement and continuously validate a Patient Safety Program (PSP) that guarantees the best conditions for the care of the Colombian people in terms of health and for which it has issued specific regulations [14, 15].

It can be thought that the pharmacovigilance programs (PVP) were part of the origin of the patient safety programs (PSP) in which the interest of investigating not only the risks associated with the drugs but with all the health care is deepened. PSPs in their philosophy extend the focus of safety in patient care and include in their objectives the inspection of activities related to health care, such as skin integrity, prevention of falls, control of medical devices, monitoring of blood derivatives, among others.

These programs incorporate in their concept the inherent risk of health care service and part of their analysis includes the evaluation of the causes of the errors or failures in the system that will allow to establish corrective actions in future risk situations for the patient. It is observed in the aforementioned a notable difference with the PVP in which the approach is directed towards the identification of ADR, its notification and quantification, without making much emphasis that at least half of them are the consequence of errors or failures in any point of the drug chain and that by definition are preventable [16].

Despite these two programs led by the WHO, the negative consequences for the patients' health are still far from being controlled or minimized due, among other reasons, to the current biomedical model that aims to solve the health issues with medical interventions, among which drugs are an essential part, and a neoliberal economy that turned health into a business model [17, 18].

One of the common points of PVP and PSP are drugs. Despite the use of common words (ADR, medication error, etc.), the same epidemiological method (risk approach) and recognition by health authorities, there does not seem to be a clear relationship between them and it has even been identified that there is an important variability in the PVP, which limits the comparability between different information systems and it hampers efforts to add data among cohorts [19].

This study characterized the reports, identified the differences in the way of classifying them and the scope of each program, with which it was possible to identify improvement opportunities in an institutional PSP.

METHOLOGY

An observational descriptive cross-sectional study with retrospective information collection was carried out where all the reports of the institutional application of the PSP were included during 2015 and there were excluded duplicated, invalid reports (report does not correspond to reality or presents some inconsistency), tests (information is introduced to verify the integrity of the application), which are related to the hospital infrastructure, correspond to personal complaints or contain insufficient information. The reports were classified according to the categories established in the document The Conceptual Framework for the International Classification for Patient Safety (ICPS) by WHO 2009 [20]. For the classification of ADR, the tools suggested by the Uppsala Monitoring Center were used, such as the Naranjo algorithm (causality), the system/ organ affected and the severity [21].

The institutional ethics committee approved the study in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and the resolution 008430 of 1993 according to the specified in article 11 of chapter I of the Ministry of Health of Colombia. The present study is a risk-free investigation, therefore, written informed consent is not required.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

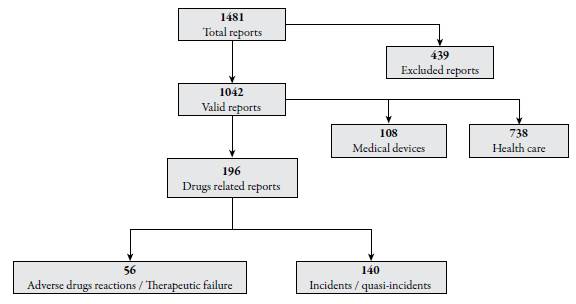

According to the database used in the study, 1481 safety cases were reported in 2015. These cases group the work of the different committees and safety groups that are part of the PSP. After the preliminary analysis, 439 (29.6%) news were discarded (from here on out reports), because they fulfill some excluded criteria, leaving 1042 total valid reports of which 196 (18.8%) were identified and are related to drugs and make up the common core between the PSP and the PVP. Figure 1 shows the process and results of the initial evaluation. The results analyzed by the authors from the point of view of the two programs are shown below.

PSP: Medication Errors

Table 1 shows the distribution of reports according to the classification of errors of the WHO where 42.8% (84/196) correspond to omission of drugs or doses, followed by 20.9% (41/196) related to ADR. Sixteen reports could not be classified in any category, so it was necessary to create 2 additional categories: "therapeutic failure" (15 reports) and "unclassifiable", corresponding to a wrong adjustment event (1 report).

Table 1 Distribution of errors according to WHO.

| Problem | N.° | % |

|---|---|---|

| Omission of drug or dose | 84 | 42.86 |

| Adverse drug reaction | 41 | 20.92 |

| Therapeutic failure | 15 | 7.65 |

| Wrong medicine | 14 | 7.14 |

| Inadequate storage conditions | 13 | 6.63 |

| Incorrect dose or frequency | 10 | 5.1 |

| Wrong information/instructions | 8 | 4.08 |

| Galenic form or wrong presentation | 4 | 2.04 |

| Wrong patient | 3 | 1.53 |

| Contraindication | 2 | 1.02 |

| Wrong way, wrong quantity | 1 | 0.51 |

| Not classifiable | 1 | 0.51 |

| 196 | 100 |

Notifiable events were formed by 61.2% (120/196) of harmful incidents which included ADR (41/120), therapeutic failures (15/120) and damage related to delay in surgery, additional examinations, rupture or drug damage or the performance of strict monitoring (64/120). The remaining 38.8% (76/196) of the reports were represented in no harm incidents.

PVP: Adverse drug reactions

There were identified 41 ADR and 15 therapeutic failures that correspond to a 5.4% (56/1040) of the total of the reports and to a 28.6% (56/196) of reports related to drugs. Their distribution is in Table 2 where it is observed that phlebitis is the most frequently reported with 36.6% (15/41), followed by hypersensitivity reactions with 19.5% (8/41) and excessive neuromuscular blockade with 12.1% (5/41).

Table 2 Distribution of adverse drug reaction (ADR).

| ADR | Drug | Severity | N.° | % |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Phlebitis | Polymyxin B, vancomicina, fenitoína, no drugs related. | Moderate | 15 | 26.8 |

| Therapeutic failure | Dexmedetomidine, midazolam, fentanyl labetalol | Moderate | 15 | 26.8 |

| Hypersensitivity reaction | Cefazolin, dipyrone, phenytoin, hyoscine, levetiracetam, morphine, piperacillin, rituximab | Moderate | 8 | 14.3 |

| Neuromuscular blockade | Rocuronium | Serious | 5 | 8.9 |

| Over-anticoagulaction | Heparin, warfarin | Serious | 4 | 7.1 |

| Emesis | Noradrenaline, no drugs related | Moderate | 3 | 5.3 |

| Agitation, anxiety | Dexmedetomidine | Moderate | 1.7 | |

| Hypertensive crisis | Oxygen | Serious | 1.7 | |

| Extrapyramidalism | Haloperidol | Moderate | 1.7 | |

| Hypoglycemia | Insulin glargine | Moderate | 1.7 | |

| Hypotension | Prazosin | Moderate | 1.7 | |

| Reverse psoriasis | Certolizumab | Moderate | 1.7 |

During the study period, 9 900 patients were treated, which shows an incidence of ADR of 0.56%. According to the affected organ system, the skin and appendage occupy the first place with 42.8% (24/56) followed by the nervous system with 23.2% (13/56). According to the severity of ADR, most of them were moderate with 82.2% (46/56) and the remaining 17.8% (10/56) were serious.

The results of the causality analysis with the Naranjo algorithm obtained a score of 7 in all cases, with the exception of rocuronium which was assigned an additional point (+8) due to the fact that the sugammadex was used to reverse the blockade, however, they all get into the PROBABLE category.

Regarding the ABC classification, 78.1% (32/41) belong to class A (phlebitis, neuromuscular blockade, overanticoagulation, etc.) and 21.9% (9/41) belong to class B (hypersensitivity reactions).

Drugs involved in the reports

The classification of drugs was carried out by anatomic group according to the Anatomical Therapeutic Chemical (ATC) Classification System [22]. It was identified that the drugs most frequently involved in the reports correspond to the N group with 32.1% (18/56), followed by C group with 10.7% (6/56), and J and M group each with 8.9% (5/56). Other groups with low percentage were L and A group. It was necessary to create "category X" (no reported drug), which corresponds to the report of an event where some problem is mentioned without a specific description of the international common denomination.

The present study identified that 1 out of 4 reports were rejected, this can be explained by some of the following reasons: incomplete socialization of the program, high healthcare burden, high professionals and students turnover (university hospital), although it can also be interpreted as a sign of dissatisfaction with co-workers or workplace conditions. These invalid reports have a negative impact on the program because the classification of the reports is done manually by a trained person and the time of reading increased.

Another finding of the present investigation was a higher frequency of the incident reports related with care (70.8%), followed by those related to drug (18.8%), and, finally, those with medical devices (10.4%). Given that the interest of this work corresponds to drugs, it can be mention that the frequency of reports related to this supply is within the numbers identified in studies such as ENEAS with 37.4% [10], IBEAS with 8,23% [16] and SYREC with 24.6% [23]. In relation to Colombian studies, some studies covering several years, and more than 5 million people have been published [24-26], but it was not possible to contrast the results, since it is used another approach and a different classification to the one used by international studies.

The findings of reports on drugs omission, inadequate storage conditions and wrong medication can be the reflection of the lack of a drug distribution system, whose purpose, precisely, is to reduce these errors [27]. These results are consistent with a study conducted in the hospitalization service of a clinic in the city of Cali (Colombia) [28] and another study conducted by Machado et al. for 8 years in ambulatory pharmacies in different cities of Colombia [26]. However, it is necessary to emphasize that the comparison of these results with other studies is difficult because of the use of different types of classification and several settings of study (community, hospital, ambulatory, etc.). For example, a recent report in England identifies the potentially inappropriate prescription as an error, as well as administration, monitoring, and dispensing errors [29]. This difficulty was reflected in the present study, so it was necessary to create categories to classify the problems of drug adequacy and therapeutic failure.

According to the typology of the notifiable events, it is identified that more than half of the reports correspond to harmful incidents. It was necessary to clarify in this section that the harm described in the PSP not only include ADR and TF that has to do with the consequences on the biological integrity, but also includes another type of harm that affects other areas of the person or the health system (delay in surgery, intensive monitoring, drug damage, etc.). The development and consolidation of the program possibly leads to the predominance of the near miss incidents report, since they are closer to prevention and constitute the first sign of incidents that may lead or not to harm. This high proportion of harmful incident reports can be related to the fact that people tend to report those events that produce harm, since those that do not bring consequences can be considered "normal" [30].

Regarding to harmful incidents, it is necessary to clarify that, from the PSP perspective, these damages are not always related to the affectation to human biology (which in PV would be called ADR), but also include aspects such as delay in surgery, intensive monitoring, drug damage, etc. According to this consideration, it is noteworthy that a little less than half of these incidents correspond to ADR and, therefore, were included in the PVP activities, while the remaining percentage of incidents, which also caused harm, was not considered. In addition, those no harm incidents reports are not analyzed, mainly due to high workload, which means that an important opportunity to manage risk is lost. This is one of the most relevant findings of the present study, since it shows that the PV should also deal with errors or infractions in order to be corrected and prevented. Some authors have identified this need and make a call so that medication errors are considered in the PVP [31, 32]. Therefore, it is necessary to visualize these findings as an opportunity for improvement, first identifying that the scope of the two programs pose as a challenge the non-duplicity of efforts, and as an opportunity, not leaving problems unattended, specifically the near miss incidents and no harm incidents.

In the referenced studies it was not possible to identify the results in terms of no harm incidents or near miss incidents. Some of them describe the results in terms of ADR or ME without considering the infractions and other notifiable events mentioned at the beginning of the paragraph. It is not possible to make a direct comparison with other studies related to the subject because of the following reasons: equal or very similar terms to refer to different things (adverse event in PV vs adverse event in PS); different terms to refer to the same (adverse event or preventable ADR in PV vs medication error in PS); lack of knowledge by the PV programs that only study ADR of medication errors that do not reach patients (near miss incidents), and medication errors that do not produce obvious damage (no harm incidents) and, finally, some discrepancies in the harmonization of terms used in the Colombian norm vs WHO (incident related to patient safety according to WHO 2009 and incident according to Minprotection 2008 and 2009).

Regarding the PVP, it is considered that the proportion of ADR reported seems low if one considers that some studies indicate much higher numbers [11, 16]. These results may also be related to underreporting, one of the main problems of passive pharmacovigilance [7]. A document prepared by Varallos et al. explains that this low report occurs for what has been called "the seven capital sins of underreporting" 1) consider that serious ADR are well documented, 2) fear of being involved in legal proceedings, 3) feeling guilty for having been responsible for the harm to the patient, 4) ambition of a group for publish serious cases, 5) lack of knowledge about how to make the notification, 6) insecurity about the report of ADR and, 7) indifference, lack of interest, time or other excuse to postpone the notification. The main causes of ADR underreporting found in the studies included in a systematic review were ignorance and insecurity, findings related to the low knowledge of professionals about drug safety analysis activities and for which, the authors propose that professional notifications can be promoted through educational interventions aimed to clarify the importance of the practice, in addition to the concepts and processes involved in these activities [30]. For the present study, this could also be the cause of the deficient registration in the institutional application and invalid reports.

The drugs related to the notification of ADR classified by therapeutic groups differ from the results found by: Machado et al. in Colombia for 7 years, De las Salas et al. in two pediatric hospitals for 6 months, Moscoso et al. in a second level hospital in Bogotá for 3 months, and the study conducted by Chaves in 31 second level institutions in the city of Bogotá for a year, where antibiotics are among the drugs that report the most ADR, although they agree that the skin is the most affected organ system [25, 33-35]. These studies also coincide in identifying the severity of ADR as moderate. Although some similarities are found, differences are also found in some of the results, this can be explained by the type of institution and the methodology used for identification (active vs. passive).

The results suggest that a greater commitment of the leaders of the programs is necessary to improve the quality of the reports, the underreporting, especially in relation to ADR. Regarding the no harm incidents or near miss incidents, it is considered that they are an opportunity for improvement to propose risk management strategies.

Although the two programs coexist in the institution and there are published studies related to patient safety and pharmacovigilance, no similar studies were found in the literature review for the present study that attempted to reflect on the relationship of the programs in specific hospitals. However, documents such as the one written by the WHO in 2014 and the EMA in 2015 allow to deduce that studying the real relationship of these programs is at the heart of the PV and PS programs [31, 36]. For almost 20 years, several authors have discussed the need for a change in the scope, approach or methods used to perform pharmacovigilance. It is possible that these findings are the result of the movement on patient safety or a societal need to counteract the growing outbreak of drug-induced iatrogenia [32, 37-43].

There is a need to broaden the vision of health surveillance systems to include aspects such as drug-related problems, medication errors and adverse reactions. It has not yet been possible to integrate and incorporate these terms into a single program, perhaps for reasons that range from the purely philosophical, to a predominance of positivism, going through political and economic causes whose analysis goes beyond the scope of this research [44-46].