INTRODUCTION

Breastfeeding has been positioned by various international organizations as a key element of child nutrition, 1 and the World Health organization recommends that it be the sole source of feeding during the first 6 months of life and a complementary source until two years of age or more if the mother and the child so desire. 2,3 It has been attributed benefits such as reduced risk of atopy, otitis, pneumonia, diarrhea and enterocolitis, 1,4-6 and it is associated with a lower incidence of obesity and other chronic diseases. Breastfeeding contributes to lower household spending,3 regulation of the hunger-saciety cycle and adequate bonding in the infant; in the mother, it reduces de risk of breast and ovarian cancer, and of osteoporosis. 4 Despite the above, it has been found that breastfeeding in various countries has been abandoned and replaced with human milk substitutes or a mixed practice (breastfeeding and substitutes). In the world, in the population from 0 to 6 months of age, the rate of exclusive breastfeeding is 40% 2; in Latin America, specifically Colombia, the rate is 46.8% and in Brazil 38.6%. 7 In Mexico, according to the Health and Nutrition Survey (Ensanut 2012), the average duration of breastfeeding is 10 months, and it is found to be exclusive in 18.5% of infants under 6 months of age in the rural areas, while the figure in urban areas is 14.5%. In both, the rate of continuation out to one year is 35.5%, and out to 2 years 14.1%. 8

In turn, social representations as a particular knowledge modality 9 play the role of shaping behaviors and communication among individuals, 10 with their logic (meaning), language and their own rights to discover and organize reality. Likewise, they depend on learning, beliefs, values, ideas, norms and sociocultural practices that enable individuals to find their place in their material world and daily lives. 11 In this sense, actions designed to promote breastfeeding must consider the social, cultural and political characteristics 12 of each geographic setting given that it is in that particular space where women build their lives, create ties with their families and the community, establish communication with health services, and receive information. All these are elements that shape their social representations 13 for decision-making regarding whether to initiate, continue or abandon breastfeeding.

If this practice is to be optimized in healthcare institutions, it is important to adopt a methodological approach to identify and understand the influence that the social context may exert, in particular rural or urban settings, considering that quantitative research suggests that a lower level of education, unfavorable financial situation and little access to information among rural women, as compared to women in urban areas, are conditioning factor for less appropriate breastfeeding. 14)

In view of the above and in an attempt at improving health education and promotion actions, the Jalisco Health Secretariat developed a qualitative research study aimed at understanding social representations regarding breastfeeding among women of Jalisco, Mexico, between 2016 and 2017. This paper reports the main results.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Design and Population

Qualitative study supported on the theoretical and methodological assumptions of phenomenology, which allow to explore the way in which women represent, learn and share the practice of breastfeeding, considering that subjectively shaped meanings can only be understood from the woman’s own insight and inner experience. 15)

The study universe consisted of beneficiaries of the Prospera Program (Social Development Program targeted to individuals in a situation of poverty, designed to expand nutrition, health, education and other wellness capabilities) living in rural and urban communities in the XIIth Health Jurisdiction, Tlaquepaque Center, Jalisco (Mexico), one of the 13 jurisdictions of the Health Secretariat.

In order to select women from the two settings (rural and urban), the starting point was the total number of health units that make up the Health Jurisdiction. Simple random sampling was used for alternate selection.

In these initial health units, a theoretical qualitative sampling was used for selecting the women with a sociodemographic profile consisting of the following: a) more than 5 years as beneficiaries of the Prospera program; b) more than 5 years living in their local area; c) pregnant or with children of less than 1 year of age. A mean of at least 4 informants and a maximum of 6 was estimated for each healthcare center for the application of the selected technique.

Sample size was determined based on the theoretical saturation of the information, i.e., up to the point where no new information is obtained or information becomes redundant, in accordance with the research themes: 1) meaning of breastfeeding; 2) meaning-generating players for the practice of breastfeeding; 3) women’s wishes regarding breastfeeding. Moreover, the researchers found it important to identify other categories that emerged during their field work, in particular those which were not considered when the research study was initially stated. 16

Based on the analysis of the initial information, the researchers decided to carry out a new random selection of other healthcare units, both urban and rural, and selected the participants based on the considerations of the theoretical sampling used initially. The theoretical saturation was reached with the analysis of the second-line units.

Procedure

The study was initiated in October 2016 and was considered completed in February 2017. Since the two researchers (one nutritionist and one nurse) had had no previous interaction with the informants and one of them had had no connection to the program, they proceeded to identify and interview key informants to be approached in the healthcare units: four physicians, one social worker, one health promoter and three nurses. Once the key informants were made aware of the objective of the study, they personally invited the women to participate in the study, in accordance with the theoretical sampling criteria.

The focus group technique, with which the two researchers had had experience, was used for gathering the information. The interviews were conducted in rooms or venues outside the healthcare unit, organized by the informants. One of the researchers (female) conducted the focus group using an interview guide while the second (male) participated as observer and made notes. A psychologist was recruited to intervene, if required, in special situations that could emerge during the interview.

The first question posed to the participants was: What is the first thing that comes to mind when you hear the word breastfeeding? The informants in each group were then allowed to engage in a dialogue, leading up to the questions proposed for the research. Each focus group lasted in average 1 hour and 30 minutes. Audio recordings were made as the means to document the information, after obtaining the written informed consent from the informants. It is worth mentioning that none of the informants dropped from the study at any time and there was no need to carry out more focus groups after the saturation point was reached.

Analysis

Several considerations cited by some authors were taken into account as a means to ensure data reliability: a) persistent and prolonged observation throughout the study; b) other studies plus the regulations on the topic were cited at the beginning and at the end of the study; c) results were returned to a group of women informants called by the key informants for confirmation and corroboration of the findings; d) data saturation was confirmed by the researchers. 17)

Audio recordings of the interviews were transcribed to text in Word and analyzed under the semiotic actantial model. This required reading and rereading of every line of text; description of contextualized first impressions of the themes considered as well as of emerging topics; surface analysis of the texts; identification of semiotic players, thematic and figurative isotopies, cognitive dimension, and reciprocal ideological relations where wishes can be identified, resulted in the text being structured in accordance with large categories with textual descriptions that documented the women’s perspectives regarding breastfeeding. 18,19

Ethical considerations

Women participated voluntarily in the study and gave their written informed consent. Thus, respect for their autonomy, self-determination and privacy was ensured. Moreover, the protocol was approved by the Research Committee and the Ethics in Research Committee of the Jalisco Central Health Secretariat Office, in compliance with the methodological, ethical and originality criteria, pursuant to Technical Standard 313. The Record Number assigned was 35/RXII-JAL/2016.

RESULTS

A total of 6 group interviews were conducted in four healthcare units, 3 in each setting, with a total of 23 informants: 13% (n = 3) were pregnant and 87% (n = 20) had children under 1 year of age. Of the total, 61% (n = 14) lived in the rural setting, with a mean of 29.4 years of age (SD ± 7.8) and a median of 4 children (range 1-6); of these women, 93% (n = 13) were breastfeeding or were in favor of doing so. The remaining women, 39% (n=9), lived in the urban setting and had a mean of 27.3 years of age (SD ± 7.1) and a median of 4 children (range 2-5); of them, 100% (n=9) were in favor of breastfeeding. The sociodemographic characteristics of the participants are shown in Table 1.

According to the research themes, the findings were classified into meanings, players and desires in relation to the practice of breastfeeding.

Breastfeeding-related meanings

Elements of meaning are identified and described in the discourse, with differences and similarities by setting (Table 2).

Meaning-generating players for the practice of breastfeeding

In the social representation of the women there are also players who contribute to the meaning of a woman’s actions. These players are typified and described in Table 3.

Table 1 Rural and urban characterization in a sample of women with children under 1 year of age. Jalisco, Mexico, 2017

| Variables | Rural setting | Urban setting | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| fr | % | fr | % | ||

| Marital Status | Married | 10 | 71 | 6 | 67 |

| Free union | 4 | 29 | 2 | 22 | |

| Single | 0 | 0 | 1 | 11 | |

| Education | Primary | 2 | 14 | 1 | 11 |

| Secondary | 9 | 64 | 5 | 56 | |

| Preparatory | 3 | 21 | 2 | 22 | |

| Bachelor | 0 | 0 | 1 | 11 | |

| Profession or occupation | Housewife | 13 | 93 | 8 | 89 |

| Employed | 1 | 7 | 1 | 11 | |

| Religion | Catholic | 14 | 100 | 8 | 89 |

| No religion | 0 | 0 | 1 | 11 | |

Source: Field work.

Regarding the description of the community actant, among women in the rural setting there is a prevailing position of empowerment regarding judgement, as illustrated by the following testimonial: “Well, it is our own right, why meddle?” However, in other cases, the community does exert an influence: “No, it is not right to breastfeed in public because you will be criticized after a while”.

Women’s wishes regarding breastfeeding

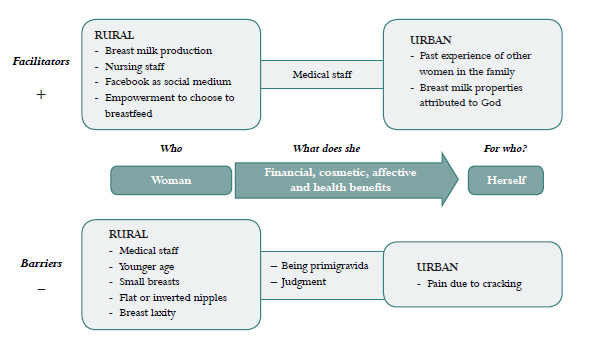

Two wishes come to light in the social representations of the informants in this study: first, the breastfeeding woman recognizes the wish to derive benefit, with different influencing elements as described in Figure 1. These benefits are reflected in the following testimonials: “You save a lot of money,” “To recover the shape of our body,” “The tight bond we mothers experience” and, “It cleans the breast and prevents breast cancer”. Aside from the benefits, it is worth noting that prejudices came across in the discourse, classified as barriers: “… sometimes they do not want to breastfeed because they claim they become floppy”. In the second wish, women expect to benefit the infant from the point of view of nutrition, psychological health, growth, development and improved physical health. These aspects are reflected in these statements: “They are the best vitamins you can give your baby,” “Babies feel safer because they feel protected,” “It helps them… grow stronger and develop more,” “They will never fall ill.” Finally, it is important to mention that no emerging categories were generated during the interviews.

DISCUSSION

Among the meanings found in this study it is important to highlight myths, characteristics of the breast and of breast milk, lesions due to the breastfeeding technique, and influence on the growth and development of the infant. Players such as healthcare staff, the hospital, Facebook as a social medium, family, God and the community are identified as influencers on decision-making. Regarding breastfeeding techniques, specifically latching on the breast, the problems (bites, cracks) mentioned by the informants in this study as barriers to maintaining breastfeeding have also been documented in other studies in Mexico and Latin America. 20,21 This supports the need for promotion and dissemination of information related to breastfeeding and infant growth and development, as well as the correct breastfeeding technique.

Table 2 Elements of meaning regarding the practice of breastfeeding in rural and urban women. Jalisco, Mexico, 2017

| Rural setting | Urban context | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Category | Description | Representative text | Category | Description | Representative text |

| Myths (conditioning factors in breastfeeding) | Informants say that younger age is associated with less experience in establishing breastfeeding | “The baby wanted to latch, but with my runny nose and not knowing what to do, the baby did not latch and I just gave up” | Breastfeeding technique (latching) | The women mentioned that pain and wounds in the nipple are reasons for choosing a different form of feeding the baby | “I could not continue because it was painful and the two nipples were bleeding… I decided to use the bottle” |

| Myths (breast characteristics) | Statement suggest that breast sizes and anatomical nipple variants are conditioning factors for breastfeeding | “...[women ] because they have small boobs or do not have the right nipple… the baby does not suckle and if the baby does not suckle, then it [milk ] does not flow” | |||

| Infant growth and development | Teeth and the ability to bite create reactions to breastfeeding | “…[The baby] teethed and I did no want to breastfeed because it bit me and it was painful, but nevertheless I did not stop” | |||

| Breastfeeding technique (latching) | Informants say that when women who breastfeed have flat or inverted nipples, alternative latching is sought | “... I saw a girl with no nipples and they tied an elastic band around her breasts to help the nipples form so that the baby could suckle” | |||

| Both Settings | |||||

| Category | Description | Representative Text | |||

| Myths (conditioning factors for breastfeeding) | Not having prior experience with breastfeeding is perceived as a limitation of the knowledge about this practice | “It is my first baby and I know practically nothing” | |||

| Myths (breast milk) | Women believe that breast milk is a medium for disease transmission | “…a sister of mine quit breastfeeding… she was told that she had to stop because she could contaminate the baby and give it the disease… it is a method of disease transmission” | |||

Source: Field work.

Table 3 Meaning-generating players for the practice of breastfeeding in rural and urban women. Jalisco, Mexico, 2017

| Rural setting | Urban setting | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Player | Description | Representative text | Player | Description | Representative text |

| Medical staff | Contrasting individual, who determines the practice of breastfeeding | “Told me I had to breastfeed but then said it would not flow because it was very stupid” | Family | The mother is the closest woman who communicates experiences and wisdom about the practice of breastfeeding | “Through my mother because I saw how she nursed my siblings… I still seek her advise now that I am married” |

| Nursing staff | Information facilitator during the prenatal period | “Nurses. During pregnancy they ask us to come in to do this [talk]: how you are going to do it, the position, and how to feed the baby” | God | Deity to which the benefits of breast milk are attributed | “Breastfeeding is good because it was made by God” |

| Hospital | Institution that promotes exclusive breastfeeding | “Even the hospitals don’t allow you to feed them the bottle. It is forbidden and there are many posters on ‘only breastfeeding, breastfeeding is the best’” | |||

| Social Medium: Facebook | Communication medium where the practice of breastfeeding is seen | “I have seen on Facebook that people have gone on strike… mothers who sit in public, almost naked, breastfeeding their babies” | |||

| Both settings | |||||

| Player | Description | Representative text | |||

| Community | Player which, according to the informants, is judgmental about public breastfeeding | “A man told my sister-in-law that she should not breastfeed in front in him” | |||

Source: Field work.

Figure 1 Benefits, facilitators and barriers perceived by women regarding the practice of breastfeeding, in rural and urban areas. Jalisco, Mexico, 2017

Another key element considered in social representations is the information received in the rural setting regarding breastfeeding, assumed to be provided by healthcare professionals (physicians and nurses) and, therefore, considered to be reliable and decisive. In contrast, other publications describe that the lack of recommendations and support from healthcare staff has a negative impact on breastfeeding. 22,23 This points to the need to position other healthcare professionals ( nutritionists, social workers and others) and to provide continuous training and support from experts that may contribute to convey adequate knowledge and ensure timely removal of myths so as to develop the necessary aptitudes and attitudes to promote and protect breastfeeding. It is also worth highlighting that the “hospital” was the sole healthcare institution mentioned by the women as a promoter of breastfeeding, revealing the lack of positioning of healthcare units as first-contact institutions in this regard.

The women in the rural setting mentioned Facebook as a source of knowledge; another similar research found that digital media may effectively illustrate the creation of ideas and practices about breastfeeding 12 and, therefore, it would be wise for the health sector to consider dissemination, communication and true knowledge around breastfeeding through these types of media (electronic social media).

The description of God as a player identified in this study in the urban setting is similar to what was reported in a different study in which women in the same setting attached divine attributes to the unique experience of breastfeeding as a blessing coming from that deity. 22 This is a relevant ideological consideration that must be taken into account in order to create empathetic communication aimed at creating a tighter bond with the healthcare providers. It has also been documented that the family (mother) is an element of support and influence in the decision to breastfeed. Consequently, it is important to expand promotion actions to include close relatives and partners; even though the latter were not mentioned in this study, they have also been found to play a supportive role for continuation of breastfeeding. 13,24,25. On the other hand, women in both settings perceive that breastfeeding in public is not considered a normal practice by the community; this has been identified as a limitation of success in other publications, 26 reflecting the need to work on practices and legislation leading to the normalization of breastfeeding as a natural right and a beneficial behavior in terms of infant feeding.

Regarding wishes, there is a similarity between the findings of this research and those of other studies, both in terms of multiple benefits 1,4-6 as well as of cosmetic prejudices (breast laxity) 26,27 perceived by the women for themselves. The same is true of the wish to benefit the infant through emotional bonding and by favoring growth and development. 22,26) This creates an opportunity to provide more information regarding other benefits of breastfeeding which were not mentioned in these results.

Finally, it is worth highlighting that all the social and cultural aspects experienced and expressed in relation to breastfeeding must be considered and respected under the right to health care and promotion.

CONCLUSIONS

There are differences and similarities in social representations on breastfeeding among women depending on the geographic setting where they develop. These are shaped by elements and players that generate meaning and are determinant factors for the initiation, maintenance or discontinuation of breastfeeding. Some of them are perceived as favoring or hindering the achievement of the benefits that breastfeeding women wish for themselves and for their infants.

text in

text in