Servicios Personalizados

Revista

Articulo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Accesos

Accesos

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares en

SciELO

Similares en

SciELO -

Similares en Google

Similares en Google

Compartir

Vniversitas

versión impresa ISSN 0041-9060

Vniversitas n.117 Bogotá jul./dic. 2008

* This article is the result of the research project "Legal, Economic and Social Policies for the Sustainable Development in Colombia" of the research group Grupo Interdisciplinario en Desarrollo y Derecho "Interdisciplinary Group in Development and Law" of the Pontificia Universidad Javeriana Law School with the financial support of the Vicerrectoría Académica.

** Ildikó Szegedy-Maszák is professor researcher of the Pontificia Universidad Javeriana, Law School in Bogotá, D.C., Colombia. She is a lecturer of sociology of law and public policies. Please send your questions and comments regarding this article to Ildikó Szegedy-Maszák through the following. E-mail address: ildiko@javeriana.edu.co

Fecha de recepción: Agosto 30 de 2007 Fecha de aceptación: Noviembre 15 de 2007

ABSTRACT

This article is the result of an interdisciplinary research project "Legal, Economic and Social Policies for the Sustainable Development in Colombia" of the research group Grupo Interdisciplinario en Desarrollo y Derecho "Interdisciplinary Group in Development and Law" implemented at the Pontificia Universidad Javeriana Law School. As a sub-project of the above mentioned research project the limitations of Corporate Social Responsibility were studied through a field research implemented at the Mining Project Cerrejón of the Department La Guajira in Colombia. Cerrejón is the largest open air coal mine in the world. The Mining Project has been developing since 26 years. During this period the indigenous community wayüu has been facing the challenges to share their original habitat with the Mining Project. This relationship between indigenous wayüu community, the Mining Project Cerrejón and the Departmental Government of La Guajira presented contradictions and has resulted in cooperation as well as fights and misunderstandings between the various actors. The social project PAICI implemented by the Mining Project Cerrejón is one of the outstanding examples of the community related aspects of Corporate Social Responsibility and not only in the mining sector. On the other hand, this project benefits only around 20% of the indigenous wayüu in the Department La Guajira , wayüus who in substantial numbers have lost their land, some of them without proper resettlement and compensation as a result of the expansion of the Mining Project. There are several questions to raise: how to match different interests such as development of a mining project, social-cultural-economic development of an indigenous group with the priorities and responsibilities of public policy making. In this article the theory of sustainable governance is proposed to analyze these questions with the firm conviction that development should find its compromises for the benefit of all actors through the functioning of an advanced system of public policies to manage conflicting interests.

Key words: corporate social responsibility, community related aspects, Cerrejón, indigenous wayüu, PAICI, socially responsible governance.

RESUMEN

El presente artículo de investigación es el resultado del proyecto interdisciplinario de investigación "Políticas Jurídicas, Económicas y Sociales para el Desarrollo Sostenible en Colombia" del grupo de investigación "Grupo Interdisciplinario en Desarrollo y Derecho" desarrollado en la Facultad de Ciencias Jurídicas de la Pontificia Universidad Javeriana. Como subproyecto del anteriormente mencionado proyecto de investigación, las limitaciones del concepto "responsabilidad social empresarial" han sido estudiadas a través del trabajo de campo en el Proyecto de Mina Cerrejón en el Departamento de La Guajira en Colombia. Cerrejón es la mina de carbón de cielo abierto más grande del mundo. El Proyecto de Mina Cerrejón existe hace 26 años. Durante este período la comunidad indígena wayüu tenía que enfrentarse con la llegada de la mina a su hábitat original. La relación entre el grupo indígena wayüu, el Proyecto de Mina Cerrejón y el Gobierno Departamental de La Guajira demostró contradicciones y resultó por un lado en cooperación, por otro lado en luchas y mal entendimiento entre los varios actores. El proyecto social Plan de Ayuda Integral a las Comunidades Indigenas (PAICI) implementado por el Proyecto de Mina Cerrejón es uno de los ejemplos más extraordinarios del aspecto comunitario de la responsabilidad social empresarial no solamente en el sector minero. Por el contrario, este proyecto social beneficia únicamente al 20% de todos los indígenas wayüu del Departamento de La Guajira, quienes como resultado de la expansión del proyecto de mina en número importante perdieron sus terrenos, ocasionalmente sin adecuada reubicación y recompensa. Surgen varias preguntas para formular: ¿Cómo se pueden reconciliar intereses diferentes como desarrollo de un proyecto de mina, desarrollo social-cultural-económico de un grupo indígena, y las prioridades y responsabilidades del Estado en proponer sus políticas públicas? Se propone utilizar la teoría de gobernabilidad sostenible para analizar estas preguntas con la firme convicción de que el desarrollo debe permitir compromisos para el beneficio de todos los actores a través del funcionamiento de un sistema avanzado de políticas públicas para manejar los conflictos de intereses.

Palabras clave: responsabilidad social empresarial, aspectos comunitarios, Cerrejón, grupo indígena wayüu, PAICI, gobernabilidad socialmente responsable.

INTRODUCTORY REMARKS

This article is the result of a field research implemented in 2007 in the Department La Guajira as a sub-project of the base line research project implemented from 2001 to 2005 by the Interdisciplinary Group on Development of Law of the Pontificia Universidad Javeriana Law School in Bogotá, Colombia. The base line project was designed to study the concept of sustainable development and its application in different fields of public policies in Colombia such as social, economic and legal policies1. It was detected that this concept was mainly used in the late 1990s and the beginning of the 2000s in the field of environmental protection.

On the other hand, Corporate Social Responsibility, understood as a complementary concept of sustainable development was also studied. It was recognized that Corporate Social Responsibility was mainly applied at that time as a particular element of business administration. The research group extended the use of this concept to analyze public-private relationships in the field of social policies2. This way the research group intended to create synthesis between concepts of sustainable development, public-private cooperation, public policy making and Corporate Social Responsibility3.

This debate brought the researchers to discuss basic questions of modern state building. Raising the question: which are the limits of social policy making. And whether there are differences regarding policy making issues between developed and developing countries. Modern welfare state theories were also discussed to evaluate their applicability in Colombia. The writer of the present article argued in 20074 that the Colombian state does not comply with the requirements of modern welfare state building.

All the above discussions of the research group resulted in continuous theory building especially in the area of Sustainable Governance. To demonstrate applicability of the above theory, a research sub-project was designed since 2006 and finally implemented in 2007. This sub-project was based on a field research in the Department La Guajira to describe relevant community related issues of Corporate Social Responsibility of Cerrejón especially as of its PAICI Program designed to help the indigenous wayüu Community.

The results of the field research were ambiguous and presented contradictions. The PAICI social projects covered about 20% of the whole wayüu population in the Department La Guajira . The projects were well designed and covered various action areas of importance for the wayüu. On the other hand, the members of the wayüu community resulted deeply divided in their opinion regarding PAICI and the Mining Project in general. It was the task of the researchers to analyze this situation. It was the theory of Sustainable Governance, which helped to clear out positions.

For this very reason, this article presents the results of the field research in the following way: in the first chapter a description of the historical development of the Mining Project Cerrejón is included; the second chapter discusses the structure and functioning of the PAICI Program. In this second chapter are five case studies included on the relationship between the indigenous wayüu community and the Mining Project Cerrejón. Finally, the third chapter is a discussion on the theory of Sustainable Governance and its application in the present field research.

HISTORY AND DEVELOPMENT OF THE MINING PROJECT CERREJON

The Mining Project, which is known Carbones del Cerrejón Limited or Cerrejón is the largest open air carbon mine in the world situated at a 69.000 acres land of the Department La Guajira in Colombia5. In 1983 a Consortium was established of a 50-50% participation between Carbocol (Carbones de Colombia S.A.) and International Resources Incorporated (Intercor) subsidiary of Exxon to initiate the exploitation. In 1999 October the Colombian State sold its participation in Cerrejón to the Consortium Anglo American plc, Billion plc and Glencore International AG; which transaction was required by International Monetary Fund – IMF as part of the fiscal adjustment program for Colombia6. In March 2001 BHP of Australia and Billiton merged; on the other hand in 2002 Exxon sold its 50% share to the Consortium resulting in a 100% control of Anglo American, BHP Billiton and Glencore. In 2006 Glencore sold its share to Xstrata.

The Mining Project Cerrejón was established on the ancient land of the indigenous group wayüu. There are 185.0007 indigenous wayüu living in the Department of La Guajira. The indigenous wayüu is an aborigine nomad group of the linguistic group Arawak, with traditional territorial distribution of the Peninsula of La Guajira, by the Caribbean Sea, which at the moment lays in Colombia as well as in Venezuela. Their nomad existence is based on the harsh weather conditions of long dry summers at their habitat. The fundamental social problem of the indigenous wayüu is the lack of water. For this reason, some families request jagüeyes8 to move to the territory of other families. Later family ties and cemetaries in the new territories result in disputes of land possession between the nomad families9. These are problems of interethnic or intraethnic nature.

The wayüu lived in poverty but in mutual respect with the Western world till the Mining Project arrived to their land. The indigenous wayüu in great number remained discontents with the activities and treatment by the Mining Project, especial in its early development. They felt ignored and abused, mainly because of how the Mining Project through the Colombian Government's Agricultural Land Office mistreated the indigenous wayüu regarding the negotiations of their land. To obtain the land of the wayüu for the exploitation of the Mining Project the scheme of tierras baldías10 was used by Incora11. The Board of Directors of Incora offered 5 times the cadastral value12 of the land to the wayüu in order to leave their lands. These negotiations were common in a territory called Media Luna, where at the moment the Bolívar Port is situated. This unfair treatment by the governmental office resulted in the systematic forced migration of the indigenous groups living in the area. The Colombian Government directly harmed the right of use of land of the indigenous group wayüu. This way the Mining Project caused serious damages through their forced intervention in the development of the indigenous group wayüu, its identity and culture.

On the other hand, since the mining started in the Department of La Guajira, a Project was also launched to help the wayüu community. This is the foundation of the Plan de Ayuda Integral a las Comunidades Indígenas-PAICI, Plan of Integral Help to the Indigenous Communities of the companies Carbocol-Intercor. PAICI dates back to 1982.

PAICI aims to increase the living conditions of the indigenous population living in the territory of influence of the Mining Project, at the same time conserving its cultural identity and looking for its self-sustainability13.

Nine years after the PAICI was launched the new Constitution of Colombia included the recognition of the indigenous population. The Mining Code in its article 121 modified by Chapter XIV of the Act 685 of 2001 established that all mining exploitation should be implemented without harming in any aspect the cultural, social and economic values of the ethnic groups occupying the territory object of the concession.

Article 129 of the Mining Code also established that those local authorities receiving royalties of the mining exploitations are obliged to direct resources to projects and services, which directly benefit aboriginal groups living in their territory14.

As the Colombian Government renewed the contract of Cerrejón till 2034, by that time PAICI projects will have a history of 50 years, which means an influence during a period of the lifetime of two generations.

There is a peculiar relation between the indigenous group wayüu, Carbones del Cerrejón Limited and the Departmental Government La Guajira.

There are health care, cultural and educational projects organized by the Department and also funds received from the national government channeled to the indigenous groups. Carbones del Cerrejón Limited finances an ethno-educational project15, as well as health care and basic sanitation through PAICI. The Secretary of Indigenous Matters of the Departmental Government implemented health care brigades to attend at places of difficult access of the Department.

On the contrary, there are two mayor threats the indigenous group wayüu faces since the development of the Mining Project started: from the Departmental Government, which was behind all violations of their rights; and from the Mining Company itself, which never provided adequate resettlement of this group or better living conditions as a compensation of all the wealth found on their territory.

For this very reason, the research of the PAICI program shows contradictions. From one hand, it is one of the most recognized examples of Corporate Social Responsibility of all mining projects not only in Colombia but worldwide. On the other hand, basic issues in the relationship between the Mining Project and the indigenous group wayüu after 26 years still remain without proper settlement.

CORPORATE SOCIAL RESPONSIBILITY AND CERREJÓN (PAICI PROGRAM)

Corporate Social Responsibility is much more than environmental responsibility or complying with applicable regulations. It requires special interest in the community affected by the activities of the company in fields such as education, culture, drinking water, health care, basic sanitation etc.16

Corporate Social Responsibility is a debated concept. Although its development is dated back to the 1980s, there are still discussions regarding its scope. It is generally accepted by all researchers, that a company should as a minimum comply with all obligatory regulations although as a result of this compliance Corporate Social Responsibility is still not achieved. Corporate Social Responsibility is to go beyond regulations and assume further responsibilities by the company on voluntary bases. The activities developed by each company as of its Corporate Social Responsibility should be evaluated on a case by case bases. On the other hand, the majority of the companies do not develop any activity of Corporate Social Responsibility. The scope and influence of Corporate Social Responsibility is still linked to the size and importance of the companies. In case of small and medium sized companies these projects are almost inexistent, especially in developing countries. Corporate Social Responsibility is implemented in many different forms. Its action areas include corporate governance, environmental protection and community development. In this article only the community development action area is analyzed in case of Cerrejón.

A considerable amount of companies gathered around the Global Compact to channel the development of their activities related to Corporate Social Responsibility. Cerrejón is one of these companies, member of Global Compact17.

The theory of Corporate Social Responsibility is proper to analyze the situation of the indigenous group wayüu situated at the territory and around the Mining Project Cerrejón, especially through describing the social projects developed by Cerrejón for the wayüu as part the PAICI Program18.

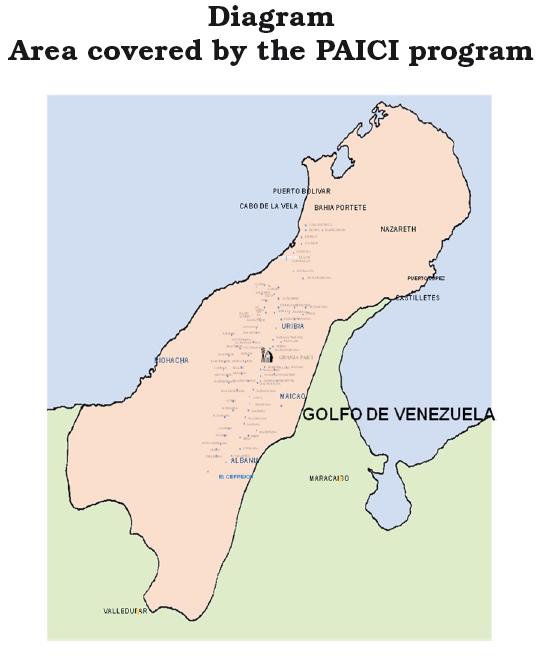

PAICI is implemented at a 150 km long and 4 km wide area situated on the two sides of the railway between the Mine and Port Bolivar. (Please see Diagram below) There is a population of 185.000 indigenous wayüu in the Department La Guajira. Approximately, 35.00019 of them receive benefits of PAICI.

The indigenous wayüu beneficiaries of PAICI seem to be satisfied with the program, which is developed with the participation of the different rancherías or family settlements of the wayüu, taking into account their necessities. Preliminary studies are developed through meetings with the communities with the participation of different professionals such as social workers and agricultural engineers. The specific projects developed as a result of the preliminary studies are approved by the wayüu community before their actual implementation.

The projects implemented through PAICI can be organized around six interrelated topics:

- Nutritional aid.

- Basic sanitation.

- Water solution.

- Ethno-education.

- Food security.

- Operational aid.

1. NUTRITIONAL AID

The nutritional aid project was developed with the Colombian Institute of Family Welfare (Instituto Colombiano de Bienestar Familia). In order to treat the urging nutritional problems of the indigenous population, there are three institutions established: Hogares comunitarios de bienestar HCB Community Homes of Welfare (attending 384 kids younger than 6 years of age) and Ayatajirawa (167 families - 835 beneficiaries); Mother & Child care (6.714 beneficiaries – providing Bienestarina20)21.

The sub-project Ayatajirawa in wayüu means working together, working united22. It is developed to beneficiate a population facing major risks living near the trash deposit of the town Rioacha. The sub-project is aimed to help head of family women, breastfeeding mothers, children, young adults, elderly people and pregnant women developing abilities of sustainability such as, proper use of natural resources, self-sufficency in providing nutrition and awarness of cultural values23.

On the other hand, the sub-project of Mother & Child care provides nutritional supplement of bienestarina to pregnant women, breastfeeding mothers and to children between 0 and 6 years old.

2. BASIC SANITATION

This Project, is designed to increase basic hygienic conditions of health care institutions such as hospitals used by the population wayüu24, on the other hand, it provides education in close cooperation with the National Educational Services (SENA) Servicio Nacional de Aprendizaje to the wayüu population in the field of basic sanitation. Basic sanitation is a major problem of the wayüu indigenous population, which is closely linked with the problem of scarcity of water, lack of sewers and drains. As another result of this PAICI project, hospitals at the region are trained to attend cases related to problems of basic sanitation such as cholera, malaria, diarrheas and dengue25.

3.WATER SOLUTION

The problems of basic sanitation are connected with the problem of the scarcity of fresh water. The PAICI program implemented a project to provide drinking water to the wayüu population, as well as to provide fresh water in general to help farming in order to increase food supply and improve nutrition26.

As part of this project an irrigation system was developed for the Indigenous Reservation of San Francisco near the town Barrancas. This irrigation system provides water for agricultural purposes such as crops and farm animals to 172 indigenous people among them 32 wayüu families.

Apart from that, the Water solution projects include development and maintenance of wells, and other water systems which contribute to develop and improve agricultural production27.

4. ETHNO-EDUCATION

The Rural Ethno education Center Kamusüchiwo'u28 was created in 1984 as a pioneer bilingual Wayüunaiki - Spanish Educational Project. Centro Ethnoeducation Kamüsüchiwo'u is a result of the 1st Congress on Ethno-education and wayüu culture, where the community requested Cerrejón to help their ethnoeducational project through the Intercultural Program of Bilingualism. In 2005 Comisión Económica para América Latina (CEPAL) recognized this Project as one of the best 45 projects of social innovation in Latin America. The center receives about 450 indigenous primary school children. The education is based on promoting wayüu tradition and culture.

The PAICI Program contributes to extend the cover of the Center to receive high school students as well.

The Center received "The British & Colombian Business and Social Awards, BSA" of the British Colombian Chamber in London and the Colombian British Chamber of Bogotá.

The idea of this ethno-educational project is to complement indigenous knowledge with scientific research results to create inter-cultural understanding29.

5. FOOD SECURITY

This PAICI Project is divided into various sub-projects designed to improve living conditions through growing plants and raising domesticated animals. There is an Experimental Farm called "Granja Experimental PAICI"30, where the experts help the indigenous wayüu to raise sheep and goats, which are the traditional domesticated animals of the wayüu. The experts also organize visits to the family settlements (rancherías) of the wayüu in order to help resolve their everyday problems in connection with the raising of domesticated animals. This project was first developed with the help of the National Educational Services (SENA) Servicio Nacional de Aprendizaje providing the project with bilingual assistants (Spanish - Wayüunaiki). The Experimental Farm was open in 1999. PAICI received co-financing from IDB – Interamerican Development Bank, as a recognition of the outstanding results of the project. The Experimental Farm and its infrastructure is designed to help the indigenous wayüu to improve living and health conditions of domesticated sheep and goats, in order to increase their number to provide better food security to this indigenous group.

There is another sub-project developed as part of the Food security project related to the Integral Community Farms. The idea of these Community Farms is to improve the conditions of growing plants. This is a pilot project which is developed in the area of Media Luna at the ranchería or family settlement called Masharerain. It gathers about 200 indigenous wayüu working together in their traditional family structure, providing them with 3000 liter of water for irrigation every two weeks31. Considering the harsh weather conditions of this deserted area, apart from providing water for irrigation, it is of crucial importance to develop forms of agriculture using less soil. These techniques are the result of traditional wayüu agricultural methods combined with latest scientific inventions. The traditional plants to be grown at the area are beans, watermelon, melon and a local tuber plant ahuyama. The Integral Community Farms are expected to provid a self-sufficient agricultural structure for the indigenous wayüu.

6. OPERATIONAL AID

The Operational aid project was developed by Cerrejón to mitigate situations related to the use and maintenance of the railway system being part of the Mining Project. These activities include education regarding use and control of the railway system, prevention of possible accidents, mitigation of disputes in connection with accidents, and mitigation of inter-ethnic disputes. Finally, this project aims to provide attention in cases of natural disasters and other emergency situations32.

The results of the PAICI program seem to be all positive at first sight. On the other hand, the directed field research developed by Diana Jaramillo Piedrahíta professional of political science and international relations of the Universidad del Rosario in Bogotá33, at the site of the Mining Project Cerrejón and at the area of influence of PAICI showed contradictions of the PAICI program and in general contradictions in the relationship between the indigenous wayüu, the Mining Project and the Departmental Government.

In the beginning of the field research design based on the revision of the related bibliography in connection with the PAICI program and its influence on the indigenous wayüu, there was an overall positive outcome expected as a result of the research project. On the other hand, the further developments seemed to be confusing and impossible to foresee the future results. The research reports were contradictory and the sources of information resulted occasionally untrustworthy. It became necessary to redesign the field research and widen its scope to recover additional information. For this very reason, this article is the final result of all the different information and impressions received, through an almost 12-month period of field research. The facts presented hereby are the result of a detailed evaluation process implemented later on by the researchers.

During the field research five cases connected with the PAICI program and the indigenous wayüu were identified, studied and described. First, the visits to the office of the Cerrejón Trust, than the visits to the Secretary of Indigenous Issues of the Departmental Government, later the visits to the town of Uribia, following by the participation at the 2nd Dialog of Mining in Colombia and its International Connections in Rioacha 9-10th of August, 2007, and finally visits to the forgotten community of Tamaquito were implemented.

CASE STUDY 1

The visits to the office of the Cerrejón Trust (Fundación Cerrejón) resulted to be the most pleasant experience. The Trust deals exclusively with the design, implementation and management of the social projects developed by Cerrejón. These social projects are directed to various communities. The most important target group is the wayüu community. It was obvious that the Trust develops projects of considerable size and impact. The written material received from the Trust regarding their social projects was well organized. There were indigenous wayüu working in the office and happy to provide services and create social development for their own community.

On the other hand, there was something notorious observed. All the reports, evaluations presented by the Trust were prepared by the Trust or companies hired by the Trust. This result was compared with the fact that in Colombia activities developed as part of Corporate Social Responsibility are organized on voluntary bases. On the other hand, the Mining Code establishes obligations for the mining projects regarding the treatment of the indigenous population living at the territory or being affected by the mining projects. It was concluded that it would be of great importance to establish the requirement of an independent reporting and supervision especially for these cases, in order to create trust between: the Mining Project, the indigenous community, the citizens in general and the State.

CASE STUDY 2

The actual Governor of the Department La Guajira is of wayüu origin. This is one of the reasons why special attention given to the issues of the indigenous community wayüu in the Department. The outlines of the public policies related to the indigenous communities are originated directly from the Office of the Governor.

There is a sub-division organized to attend issues related to the indigenous groups. It is called Secretary of Indigenous Matters (Secretaría de Asuntos Indígenas). The main projects of the Secretary are organized around health care and fresh water projects. The Secretary signed an agreement of cooperation with the United Nations Development Program, which consists of distributing water using 18 trucks in three different zones South, North and Alta Guajira. The water is stored using the community water storage systems and it is distributed by the community34. The Mining Project Cerrejón participates in providing the communities with plastic barrels to store the water distributed by the Secretary35.

The Legal and Territory Unit of the Secretary of Indigenous Matters has an attorney of wayüu origin. This person has important role in resolving conflicts and conciliate in issues such as territorial disputes, intra-community violence etc. There is also an educational program on human rights implemented for the wayüu community 36.

All the above projects are developed in close cooperation with the wayüu community, and the Departmental Government through the Secretary of Indigenous Matters and the Mining Project Cerrejón. On the other hand, it was observed that there are possible action areas not covered by the above entities, as well as territories not covered by any of these services at all. There is also time wasted with discussions between authorities and also in the communities. It was concluded that these are some of the reasons why there are territories in the Department of La Guajira, where the wayüu receive excellent social services; on the other hand, the majority of the indigenous population still remains in a vulnerable situation. In order to demonstrate the above differences, the case studies in Uribia and Tamaquito are presented. Uribia, a town of flourishing cultural life and social services, and Tamaquito struggling with the problem of posible disappearance.

CASE STUDY 3

The indigenous community of Uribia is the farest located community from the Mine. Still the PAICI projects have an influence at their territory. The opinions received at Uribia regarding the PAICI Program present contradictions. Some community members support eagerly the social projects of Cerrejón. One of them is Bibiana Costam Epinayüu, she is a primary school teacher. She expressed her gratitude to Cerrejón, recognizing the positive aspects of the social projects implemented through PAICI such as primary school education, health care, water supply and the PAICI Farm with its special programs for plant growing and goat keeping.

On the other hand, Ana Angélica Arens Gouriyüu had a totally negative opinion about Cerrejón and PAICI. It is very interesting that the two women have very similar cultural backgrounds; Ana Angélica Arens Gouriyüu is also a specialist in education. She also shows signs of influence of Western culture in her way of dressing and way of living, but she also keeps the wayüu traditions. Ana Angélica Arens Gouriyüu confessed that she personally received no support of whatsoever nature from Cerrejón. At the same time, she did not recognize positive aspect of the influence of the Mining Project neither for her family nor for her community in general.

It was difficult to understand these differences between the two opinions. It was clear that there are positive signs of the development of the PAICI projects in Uribia. On the other hand, it remained also obvious that not all members of the community benefit the same way from these projects. It was one of the alerting signs regarding the quality and cover of these social projects developed through PAICI by Cerrejón.

CASE STUDY 4

The above suspicion only deepened after participating at the 2nd Dialog of Mining in Colombia and its International Connections in the town of Rioacha the 9-10 of August, 2007. The existing controversies of the social projects developed through PAICI and in general regarding the influence of the Mining Project became more obvious listening to the confessions of the affected community members. Whereas, at the offices of Cerrejón, at the Secretary of Indigenous Affairs and in the community of Uribia, the majority of the wayüu population seemed to be satisfied with the social projects of PAICI and in general with the influence of Cerrejón, at this 2nd Dialog of Mining in Rioacha, there were participating members of the wayüu community dissatisfied, sad, angry and desperate with Cerrejón. There was a sense of fear perceived during this 2nd Dialog of Mining in Rioacha. Altough the wayüu community members participated at the plenary sessions and expressed their problems, the opinions expressed at the corridors seemed to be much harsher.

One of these opinions was of Mr Diomédez Cardona. He expressed his anger with Cerrejón, with the municipality and the Departmental officers. He received no recognition either compensation for the land he lost as a result of resettlement by Cerrejón. He said that he was tired with the promises, long negotiations and meetings with Cerrejón and the Department, which in the end always terminated without any result and even strange parties paid by Cerrejón and the department La Guajira.

CASE STUDY 5

Finally, as a result of the field research, the sad case of the wayüu community of Tamaquito was discovered. The indigenous community wayüu of Tamaquito is located only 4 kilometers from the actual explotation of the Mining Project Cerrejón. On the other hand, their problems do not start with receiving or not help from Cerrejón. Their main problem is disappearing or not, losing their existence as community as such or not. What are the origins of these problems? From one hand, they are not recognized as indigenous wayüu by the Departmental Government of La Guajira. They are considered as farmers or land workers. It means that they do not receive any help neither from the Departmental Government nor from Cerrejón. They face the eminent danger of being resettled without any further help by the Departmental Government in order to provide new land to the Mining Project Cerrejón for the explotation of carbon. Why is this danger so eminent? The same type of resettlement has recently occurred to the afro origin community Tabaco. Furthermore, it was the afro community Tabaco, which gave the last chance of commerce for the wayüu of Tamaquito. Since this community of Tabaco was resettled, the wayüu of Tamaquito has nothing else to do but walk 2 kilometers to work at the nearby farms or commute to Venezuela. Their traditional activities of nomad goat keeping and hunting are totally limited by the nearby Mining Project Cerrejón. If their animals get into the Mining zone, the security guards do not let them enter to search for their animals37.

All the above examples demonstrate the contradictions of not only the development and results of the social projects of Cerrejón but also the actual functioning of the Mining Project of Cerrejón. From one hand, it is only 20% of all wayüu community, who benefit from the social practices of Cerrejón. On the other hand, whatever positive effect these social projects might have, they are seemed to be accompanied by the negative effects of the general functioning of Cerrejón.

As in the next chapter of this article is analyzed, it cannot be considered as socially Sustainable Governance, to implement social projects (in this case by Cerrejón and the Departmental Government of La Guajira), if these social projects are financed with resources from a Mining Project developed based on taking away the land of the wayüu without proper compensation and without showing and demonstrating understanding what it really means losing ancient lands and the negative effects of sharing habitat with an industrial project being the largest open air coal mine in the world.

SOCIALLY RESPONSIBLE GOVERNANCE

The Mining Project Cerrejón will function at least until 2034 as of current contractual terms between Cerrejón and the Colombian Government. The Mine will most probably extend its exploitation to additional territories, which belong at the moment to the indigenous wayüu community. Tamaquito is one of these territories from where the population must be resettled shortly. What can this indigenous community expect from the Departmental Government or from Cerrejón in terms of proper resettlement, compensation and social development projects, if they are not even recognized as indigenous community at the moment?

It means that the indigenous wayüu are against the development of the Mining Project Cerrejón? Are they against progress in general? Do they want to live as a nomad society struggling with the scarcity of water in the middle of the desert of La Guajira? Not at all. As they put it "Mining yes, but NOT like this". Why is it still a question after 26 years of functioning of the Mining Project that a proper resettlement and compensation is a minimum requirement for the indigenous community wayüu? It was the international NGO Permanent Action for Peace (Acción Permanente por la Paz) with the participation of organizations from the United Kingdom, United States, Switzerland, Canada and Sweden, which after severe violations of human rights against the wayüu community and the fight of the wayüu against the Mining Project, finally decided to help to create opinion in the international level to protect the wayüu. This NGO implemented its activities in countries where the coal produced in Cerrejón were commercialized. They expressed their deepest concerns regarding the relationship between the indigenous community wayüu, Cerrejón and the Departmental Government of La Guajira.

Controversially, it is the background of the development and economic success of the Mining Project Cerrejón, which is at the same a multinational company, member of Global Compact; internationally recognized for its social projects. It must be recognized that the major violations of human rights against the wayüu community are dated back to the 1980s and early 1990s when the owners of the Mining Project were Carbocol-Intercol. Notwithstanding, it was always the Colombian Government through its Departmental Government of La Guajira behind these violations of human rights, participating in the negotiations with the wayüu regarding their resettlement and compensation. It is the Departmental Government which does not recognize the indigenous status of the community of Tamaquito, which could facilitate their proper resettlement.

The theory of Amartya Sen38 regarding sustainable development in form of basic liberties has major application in the analysis of the case of the indigenous wayüu. According to this theory, there is no possibility of development for any community, if basic necessities of their members are not satisfied.

Although there are important social projects implemented through PAICI for the indigenous wayüu community such as Ayatajirawa in the field of health care and the Kamusüchiwo'u Center in the field of ethno-education, these projects scarcely attend a 20% of all wayüu population in the Department La Guajira.

Does it mean then that the Mining Project of Cerrejón is responsible to attend all basic necessities of the whole wayüu community in the entire Department La Guajira? The question can be rephrased: when there is a successful business entity operating at a given territory, is it obliged to attend the social needs of the entire community living at its territory of interest? These questions are basic aspects of not only the theory of Corporate Social Responsibility but of certain state theories such as; Sustainable Governance.

The article of Jonathan B. Wiener "Toward Sustainable Governance"39 starts with the affirmation: "it is obvious but frequently forgotten that the government is not an exogenous solution of human problems, government is a human institution".

Wiener develops his criticism against "excessively weak" or "excessively harsh" acts of governments especially in the field of environmental policies. He considers that these policies are harmful for the development of governance and the development of the society in general. In order to mitigate this situation, he suggests integrating the fragmented system of public policies, especially environmental policies to create "Sustainable Governance".

The writer of this article agrees with the basic findings of Wiener, but she suggests extending the concept of "Sustainable Governance" to all fields of public policies especially social, economic and cultural policies. Therefore, the implementation of such an extended concept of "Sustainable Governance", applicable for the necessities of human society in the XXI century, requires a rethinking of broader concepts such as state, government and governance.

The World Bank and the Organization of Economic Cooperation and Development –OECD– also developed its concept on "socially sustainable development"40. As a practical element of analysis of governance, they implement the concept of "social responsibility of governments" based on "civil society participation" in order to create "open governments".

On the other hand, in Colombia the base line document of public policy planning 2019 Vision Colombia, 2nd Century (2019 Visión Colombia II. Centenario)41 presented four major public policy objectives: "economy, which provides increased social security; society with more equality and solidarity; society of free and responsible citizens; State (or Government) to the service of the citizens.

There are various groups of professionals working on concepts similar to Sustainable Governance42. It is also an important aspect that recent theories usually include the social dimension of Sustainable Governance.

How to apply Sustainable Governance related to the indigenous group wayüu, Cerrejón and the Department La Guajira? The path to find the answer to this question is linked to the theories of Amartya Sen and the theory of Corporate Social Responsibility.

The theory of Amartya Sen is based on a new understanding of human development through liberties. For this very reason, the role of government and governance should be understood in a different way. Citizens are free to decide and create the kind of development they want, on the other hand, it is the state, which is responsible to provide them with basic services. Obviously, it is not a state of social assistance. It is a responsible state for promoting sustainable development for its citizens. Sustainable Governance in this sense requires a government fully aware of its limitations. A state structure, which is capable to provide basic services to all citizens; on the other hand, it should be designed to promote the participation of all citizens to create progress.

How to achieve these basic principles? First of all, the state structure should be based on the principles of participative democracy, of a decentralized state, where grassroot movements are encouraged through mechanisms of civil society participation to propose, initiate, implement and evaluate public policies. To make this functional, there is a need to diminish central administration and empower departmental and regional administrations to actually govern on their territories. At the same time, a detailed supervisory system of the decentralized administration should be implemented. Decentralized governmental entities are much more capable to create and maintain dialog with civil society in order to promote cooperation between all actors. As Wiener put it, state structure or government is not different from human society. As I myself understand it, government is a result of human society, the way of organization through human structures to fulfill the actual necessities of a group of human beings. That way government is an integral and functional part of society.

The writer of this article has a slightly different understanding of Corporate Social Responsibility compared to current mainstream theories43 she writes about Corporate Social Responsibility using certain concepts of John Ruggies although with a specific point of view of Sustainable Governance44. Corporate Social Responsibility is to promote cross-sectoral understanding. It establishes relationship especially in the field of public policy building between all sectors. According to the consideration of the author of the present article, Social Responsibility is the manifestation of Sustainable Governance for the companies. There are companies with size and importance of middle income states in the world. On the other hand, the obligations and responsibilities of a company may not be comparable with that of a state or government. Companies were created for a different social purpose with a different social responsibility than governments. Notwithstanding, there is no such way to create public policies in the modern state without continuous cooperation between all actors, especially companies and governmental actors. Corporate Social Responsibility then, is the active cooperation in the development of the society promoted by the companies with the participation of all actors. There are shared responsibilities by all actors, on the other hand, to create Sustainable Governance, specific responsibilities of each actor should be carefully established and divided in a new kind of division of labor.

How is the theory of Sustainable Governance applicable to the case of the Mining Project Cerrejón? According to the writer of this article, one of the most straightforward answers is through the idea of the division of labor.

It is the national government in close cooperation with the Departmental Government of la Guajira to provided basic services to all citizens of the Department La Guajira (in our specific case). Basic services include: free movement, culture, education, fresh water and sewage, transportation health care, healthy environment, housing, security, as well as public policies to promote working possibilities. It is one of the major responsibilities of the government to create and promote cooperation between government and all actors. As the wayüu community has a special condition of being a minority group, all other actors, including government, private sector and civil society have special responsibility in maintaining a positive discrimination towards them.

Dealing with a Mining Project, further responsibilities of the governmental entities must be established: mitigation of all negative effects of a large-scale industrial project such as environmental and cultural effects of resettlement or any other effects on the population; conciliation between Mining Project and affected population; and participation in long term planning of all externalities of a project which lasts the lifetime of various generations.

How about the citizens and their responsibilities? The citizens' major responsibility is to participate in the development of human society. This participation is from one side to develop their own life projects; on the other hand, it also requires a participation in community development, such as representation of community interests.

The civil society organizations are created to channel communication between citizens and other social actors such as government and private sector actors. For this reason, civil society organizations are integral part of the society, they should not be different from what the citizens and their actual interests represent.

For this very reason, the wayüu community cannot be only considered as passive subject of the Mining Projects Cerrejón. They are obliged to act and participate in community matters. On the other hand, it must be also considered that not all social actors have equal position to act in the society. Where endangered groups are detected, public action should be primarily directed to enable participation in community matters. It is one of the most important, although least studied aspects of positive discrimination.

Finally, Cerrejón is an example of private sector actors. Companies are supposed to generate wealth in the society through implementing its business project and creating jobs as a contribution to economic and social development. It is also expected that business activities are implemented without generating negative externalities for the society. On the other hand, it is also obvious that in case of certain business activities (such as mining), which is based on the use of natural resources, there is an interference with the natural environment, habitat of the members of human society. Therefore, there is a special environmental and social responsibility derived from all business activities, in these high environmental and social risk businesses such as mining. There should be a reasonable proportionality between the type of business activity developed and the responsibility assumed. Certain issues of business responsibility are regulated in the legal system as liability. On the other hand, there is a full range of responsibilities, which can be assumed on voluntary bases by the companies. Current studies on Corporate Social Responsibility usually focus on this second group of responsibilities. Notwithstanding, mining is a special case, because as analyzed above, the Mining Act in Colombia establishes social responsibility of the mining companies towards the affected population.

It is obvious that PAICI is not the result of the mercy of Cerrejón towards the wayüu community. It is their social and legal obligation to protect and help the communities affected by the Mining Project. On the other hand, the boundaries and limitations of Corporate Social Responsibility are still not clear. There is a need to treat these questions in a communication process between all actors. As a result of the above, public policy mechanisms should be implemented to help the above process. Notwithstanding, the presence of public policy mechanisms should result in establishing legal obligations only if, all actors are in agreement. Therefore, Corporate Social Responsibility is one of the areas, where public policy mechanisms should be considered as forum of communication between all actors.

As we saw before, division of labor should mean a clear structure of responsibilities. On the other hand, this division of responsibilities should result in unity, a unity to create common issues, a human undivided society based on advanced forms of communication.

CONCLUSIONS

At the begging of this research project, the main question raised was how the social projects implemented by Cerrejón may contribute to the development of the indigenous community wayüu at the zone of influence of the Mining Project Cerrejón in the Department of La Guajira. On the other hand, the frequent visits of the 12 month-field research implemented by the professional Diana Jaramillo Piedrahíta to Riohacha, Maicao, Uribia, Tamaquito and the Mining Project Cerrejón resulted in discovering seemingly irresolvable contradictions.

It became obvious that the social projects implemented through the PAICI program by Cerrejón with the participation of the Departmental Government of La Guajira, contributed to the sustainable development of the indigenous community wayüu. These projects not only contributed to improve living standards in the fields of health care, agricultural production, drinking water, basic sanitation and education; but also aimed to maintain and develop cultural identity of the wayüu community.

On the other hand, there is only limited information available for the wayüu community and for the general community regarding these social projects and their impacts. There are publications available from Cerrejón, but there is no written material from the part of the Departmental Government of La Guajira. It results that without public control these projects are implemented on voluntarily bases by Cerrejón. For this very reason, they show all topical problems of all Corporate Social Responsibility projects developed on voluntary bases in the world: lack of comparable information, therefore, lack of control, lack of long-term planning, therefore, failures in self-sustainability, lack of organized public-private cooperation, therefore, failures in real social impact.

According to the publications of Cerrejón, the Mining Project is one of the outstanding examples of Corporate Social Responsibility. The main beneficiaries of these Corporate Social Responsibility projects are the wayüu community. On the other hand, there are about 185.000 wayüu living in the Department La Guajira, whereas the PAICI program covers about 30.000 wayüu beneficiaries.

How to resolve the above questions and problems? As analyzed before, declaring obligatory Corporate Social Responsibility is not the way. The recommendation is to implement concepts such as Sustainable Governance. It can create composite responsibilities for private and public sector actors. It might result in the modernization of not only public policy making based on public-private cooperation but in the modernization of (in our case) the Colombian State.

FOOTNOTES

1SZEGEDY-MASZÁK, ILDIKÓ and HERNANDO GUTIÉRREZ PRIETO. "Sustainable Foreign Direct Investment and Sustainable Technology Transfer" Vniversitas 104 (2002): 343-368.2SZEGEDY-MASZÁK, ILDIKÓ, "Corporate Social Responsibility Public Policy Issues of Cross Sector Partnerships in Colombia". In Pontificia Universidad Javeriana. Facultad de Ciencias Jurídicas. Colección Investigaciones 4. Rethinking the Colombian Path to Sustainable Development Anthology of essays dedicated to discuss new tendencies of theory and practice regarding Sustainable Development in Colombia (Bogotá, D.C., Pontificia Universidad Javeriana. Facultad de Ciencias Jurídicas, 2008).

3Please see the results of this research group on sustainable development in Pontificia Universidad Javeriana. Facultad de Ciencias Jurídicas. Colección Investigaciones 4. Rethinking the Colombian Path to Sustainable Development Anthology of essays dedicated to discuss new tendencies of theory and practice regarding Sustainable Development in Colombia (Bogotá, D.C., Pontificia Universidad Javeriana. Facultad de Ciencias Jurídicas, 2008).

4SZEGEDY-MASZÁK, ILDIKÓ, Proposal of a Colombian Welfare State analysis based on European public policy welfare state findings. In Pontificia Universidad Javeriana. Facultad de Ciencias Jurídicas. Estudios de Derecho Internacional 10. Reflexiones sobre Derecho Global (Bogotá, D.C., Pontificia Universidad Javeriana. Facultad de Ciencias Jurídicas, 2007).

5Carbones del Cerrejón Limited. (http://www.cerrejoncoal.com (accessed August 29, 2008)).

6Programa de ajuste (adjustment program). Detailed economic program, usually backed by IMF financing, based on the analysis of the economic problems of the member state to establish measures to be applied in the fields of monetary and fiscal policies, balance of payment and in structural issues in order to stabilize the economy.

7Sistema Nacional de Información Cultural. (http://www.sinic.gov.co/SINIC/ColombiaCultural/ ColCulturalBusca.aspx?AREID=3&SECID=8&IdDep=44&COLTEM=216 (accessed August 29, 2008)).

8Drinking water fountain; in Barrera Monroy, Eduardo. Mestizaje, comercio y resistencia. La Guajira durante la segunda mitad del siglo XVIII. (Bogotá, D.C., Instituto Colombiano de Antropología e Historia, 2000) p. 39.

9There are three main aspects of the territorial control:

(1) Origin - continuous occupation of territory by a family group called woumaiinpa'a "Home Guajira". Methods to prove: existence of cemeteries.

(2) Adjacencies - based on center of family life (cemetery, fields, source of water etc.).

(3) Subsistence; the social recognition by the indigenous wayüu of the exploitation of natural resources adjacent to its traditional land.

In Guerra, Weildler. La disputa y la palabra: la ley en la sociedad wayüu. (Bogotá, D.C., Ministerio de Cultura, 2002) p. 56.

10Land without specific use in the ownership of the Colombian State.

11Instituto Colombiano de Reforma Agraria.

12Cadastral registry, it is not a real measure of the value of land, it is a tax based on the use of land. It was used to mislead the indigenous wayüu community, because it did not reflect the real value of their land.

13PAICI 20 años abriendo caminos 1982-2002. Año 2002. Cerrejón.

14Mining Code. Modified by Act 685 of 2001. Diario Oficial n° 44.545, September 8, 2001.

15Bilingual Education Wayüunaiki - Spanish, combination of indigenous and public education.

16NÚÑEZ, GEORGINA. La responsabilidad social corporativa en un marco de desarrollo sostenible. (http://www.eclac.cl/dmaah/proyectos/ediespa/docs/ceads.pdf (accessed August 29, 2008)).

17Global Compact is a program of the United Nations based on the 10 principles of human rights, labor rights, environmental rights and the fight against corruption. (http://www.pactomundial.org/index. asp?MP=1&MS=1&MN=1&r=1280*800 (accessed August 29, 2008)).

18Resumen PAICI. Document in electronic form. Received from: NORA JIMÉNEZ, Fundación Cerrejón.

19Data received from NORA JIMÉNEZ. Coordinator of PAICI (July 19, 2007).

20Mixture of local plant powder, with added milk powder enriched with vitamins and minerals with high nutrition value. (http://www.bienestarfamiliar.gov.co/espanol/bienestarina.asp (accessed August 29, 2008)).

21Presentación Básica de la Fundación Cerrejón. Document in electronic form. Received from: NORA JIMÉNEZ, Fundación Cerrejón.

22ESCOBAR, LUZ MARÍA. Mundo Cerrejón 50 (2006): 4.

23ESCOBAR, LUZ MARÍA. Mundo Cerrejón 50 (2006): 5.

24PAICI 20 años abriendo caminos 1982-2002. Año 2002. Cerrejón. p. 19.

25PAICI 20 años abriendo caminos 1982-2002. Año 2002. Cerrejón. p. 21.

26MIRIAM DE FLORES, Las mejores prácticas, carbón para el mundo progreso para Colombia June (2005): 44.

27MIRIAM DE FLORES, Las mejores prácticas, carbón para el mundo progreso para Colombia June (2005): 44.

28Centro Ethno-education Kamüsüchiwo'u is a result of the 1st Congress on Ethno-education and wayüu Culture, where the community requested Cerrejón to help their ethno-educational project through the Intercultural Program of Bilingualism. In 2005 CEPAL recognized this Project as one of the best 45 projects of social innovation in Latin America.

29Interview with Bibiana Costam Epinayü.

30The Experimental Farm PAICI, is located at kilometer 63 between the Mine and Port Bolívar, with an extension of 6 acres of territory, including a water tank of 12000 liters and a stable for 100 goats, a conference centre and offices.

31Revista Mundo Cerrejón 47 (2005): 23.

32Presentación Básica de la Fundación Cerrejón. Document in electronic form. Received from: NORA JIMÉNEZ, Fundación Cerrejón.

33The field research was designed and supervised with the help of our research group Grupo Interdisciplinario en Desarrollo y Derecho "Interdisciplinary Group in Development and Law".

34Interview Secretaría de Asuntos Indígenas. MARI CRUZ June, 2007.

35Interview Secretaría de Asuntos Indígenas. MARI CRUZ June, 2007.

36Interview Secretaría de Asuntos Indígenas. MARI CRUZ June, 2007.

37Interview with Jairo Fuentes Epinayü. Indigenous Community of Tamaquito. August 10, 2007.

38SEN, AMARTYA. Desarrollo y libertad. (Bogotá, D.C., Planeta, 2001).

39WIENER B., JONATHAN. Toward sustainable governance, 2000. (http://www.duke.law.edu. (accessed August 28, 2008)).

40CADDY, JOANNE, and PEIXOTO, TIAGO and McNEIL, MARY. Beyond Public Scrutiny: Stocktaking of Public Accountability in OECD Countries. (Washington D.C.: World Bank Institute, Working Papers, 2007).

412019 Visión Colombia II. Centenario. (http://www.presidencia.gov.co/sne/plan2019.htm. (accessed August 28, 2008)). [ Links ]

42In this article only certain theories of Sustainable Governance are presented. In general the theories of Sustainable Governance were developed around 2000. They are mainly linked to environmental policies such as the theory of Wiener. On the other hand, it is an interesting development that the World Bank and OECD included civil society participation in their understanding of socially Sustainable Governance, which gives strength to the application of this concept in the social field.

43Just to mention some of the sources of these theories: Green and White Books of the European Union, World Business Council for Sustainable Development, World Bank, Global Compact, Association of European Trade Unions etc.

44Professor John Ruggie is a Special Representative of the Secretary-General on the issue of Human Rights and Transnational Corporations and Other Business Enterprises, has argued:

"States" have a duty to protect human rights;

"Corporations" have a responsibility to respect human rights; and

"States" have a duty to ensure that when and if corporations fail to respect human rights, these failures be investigated, punished and redressed.

It can be understood as a reassertion of a more traditional division of labour between business and government: A reassertion of the belief that businesses should predominantly be concerned with the production of goods and services (and obeying laws and more generally recognized moral precepts); whilst governments should be concerned with the establishment and enforcement of these "rules of the game"". (http://www.nottingham.ac.uk/business/iccsr (accesed September 10, 2008)).

BIBLIOGRAFÍA

2019 Visión Colombia II. Centenario. http://www.presidencia.gov.co/sne/plan2019.htm. (accessed August 28, 2008)

BARRERA, MONROY, EDUARDO. Mestizaje, comercio y resistencia: la Guajira durante la segunda mitad del siglo XVIII. Bogotá, D.C., Instituto Colombiano de Antropología e Historia, 2000. [ Links ]

CADDY, JOANNE, and PEIXOTO, TIAGO and McNEIL, MARY. Beyond Public Scrutiny: Stocktaking of Public Accountability in OECD Countries. Washington D.C.: World Bank Institute, Working Papers, 2007. [ Links ]

Carbones del Cerrejón Limited, Colombia. www.cerrejoncoal.com. (accessed August 28, 2008). [ Links ]

COOPER, STUART. Corporate social performance a stakeholder approach, Aldershot: Ashgate, 2004. [ Links ]

CROWTHER, DAVID ED. Perspectives on corporate social responsibility, Aldershot: Ashgate, 2004. [ Links ]

Cooperación de la Unión Europea con América Latina Guía de Preparación del Plan Operativo Global POG. Brussels: European Commission, 2000. www.delcol.cec.eu.int. (accessed August 28, 2008) [ Links ]

DANIELS, JOHN and RADEBAUGH, LEE. Negocios internacionales. Harlow: Pearson Education, 2000. [ Links ]

Energía, desarrollo y calidad de vida. Medellín: Universidad de Antioquia, Expouniversidad, 1999. [ Links ]

FRESNEDA, OSCAR. Índice de calidad de vida. Estudios Monográficos, Cuadernos de Investigación Bogotá, D.C., Instituto Distrital de Cultura y Turismo, Observatorio de Cultura Urbana, 1998. [ Links ]

GONZÁLEZ COUTURE and GUSTAVO ADOLFO. ¿Qué tan ética es la responsabilidad social empresarial y qué tan libre soy para ser responsable? Bogotá, D.C., Universidad de los Andes, 2007. [ Links ]

GUERRA, WEILDLER. La disputa y la Palabra: la ley en la sociedad wayüu. Bogotá D.C.: Ministerio de Cultura, 2002. [ Links ]

HABISCH, ANDRÉ ED. Corporate social responsibility across Europe. New York: Springer, 2005. [ Links ]

HOPKINS, MICHAEL. The planetary Bargain corporate social responsibility comes of age. New York: Macmillan, 1999. [ Links ]

International Centre for Corporate Social Responsibility (ICCSR) at the Nottingham University Business School. http://www.nottingham.ac.uk/business/iccsr (accessed September 10, 2008). [ Links ]

Las mejores prácticas, carbón para el mundo progreso para Colombia, 6 (2005). [ Links ]

LUO, YADONG. Global dimensions of corporate governance, Oxford: Blackwell Publishing, 2007. [ Links ]

McINTOSH, MALCOLM. Raising a ladder to the moon the complexities of corporate social and environmental responsibility. New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2003. [ Links ]

Mining Code. Modified Act 685 of 2001. Diario Oficial n° 44.545, September 8, 2001. [ Links ]

NÚÑEZ, GEORGINA. La responsabilidad social corporativa en un marco de desarrollo Sostenible. Washington D.C.: CEPAL, División. Desarrollo Sostenible y Asentamientos Humanos. http://www.eclac.cl/dmaah/proyectos/ediespa/docs/ceads.pdf. (accessed August 28, 2008). [ Links ]

PAICI 20 años abriendo caminos 1982-2002. Año 2002. Cerrejón. [ Links ]

Pontificia Universidad Javeriana. Facultad de Ciencias Jurídicas. Colección Investigaciones 4. Rethinking the Colombian Path to Sustainable Development Anthology of essays dedicated to discuss new tendencies of theory and practice regarding Sustainable Development in Colombia. Bogotá, D.C.: Pontificia Universidad Javeriana. Facultad de Ciencias Jurídicas, 2008. [ Links ]

Revista Mundo Cerrejón 47. (July 2005). [ Links ]

Revista Mundo Cerrejón 49. (April 2006). [ Links ]

Revista Mundo Cerrejón 50. (October 2006). [ Links ]

ROTH DEUBEL, ANDRÉ-NOEL. Políticas públicas: formulación, implementación y evaluación. Bogotá: Ediciones Aurora, 2002. [ Links ]

SEN, AMARTYA. Desarrollo y libertad. Bogotá, D.C., Planeta, 2001. [ Links ]

SIERRA MONTOYA, JORGE EMILIO. RSE responsabilidad social empresarial: lecciones, casos y modelos de vida. Bogotá, D.C., Seguros Bolívar, 2007. [ Links ]

Sistema Nacional de Información Cultura www.sinic.gov.co/SINIC/ColombiaCultural/ ColCulturalBusca.aspx?AREID=3&SECID=8&IdDep=44&COLTEM=216 (accessed August 28, 2008) [ Links ]

SOLARTE RODRÍGUEZ, MARIO ROBERTO ED. Manual para la elaboración del reporte de sostenibilidad compromete RSE. Bogotá, D.C., Confecámaras, 2007. [ Links ]

SOUBBOTINA P, TATIANA and SHERAM A, KATHERINE. Beyond Economic Growth. Washington, D.C., The World Bank, 2000. [ Links ]

SZEGEDY-MASZÁK, ILDIKÓ, "Corporate Social Responsibility Public Policy Issues of Cross Sector Partnerships in Colombia". In Pontificia Universidad Javeriana. Facultad de Ciencias Jurídicas. Colección Investigaciones 4. Rethinking the Colombian Path to Sustainable Development Anthology of essays dedicated to discuss new tendencies of theory and practice regarding Sustainable Development in Colombia. Bogotá, D.C., Pontificia Universidad Javeriana. Facultad de Ciencias Jurídicas, 2008. [ Links ]

SZEGEDY-MASZÁK, ILDIKÓ, Proposal of a Colombian Welfare State analysis based on European public policy welfare state findings. In Pontificia Universidad Javeriana. Facultad de Ciencias Jurídicas. Estudios de Derecho Internacional 10. Reflexiones sobre Derecho Global. Bogotá, D.C., Pontificia Universidad Javeriana. Facultad de Ciencias Jurídicas, 2007. [ Links ]

SZEGEDY-MASZÁK, ILDIKÓ, and HERNANDO GUTIÉRREZ PRIETO. "Sustainable Foreign Direct Investment and Sustainable Technology Transfer" Vniversitas 104 (2002):343-368. [ Links ]

United Nations, Global Compact. 2000. http://www.onu.org/sc/globalcompact.pdf (accessed August 28, 2008). [ Links ]

WERTHER, WILLIAM B. Strategic corporate social responsibility stakeholders in a global environment. London: SAGE Publications, 2006. [ Links ]

WIENER B., JONATHAN. Toward Sustainable Governance, 2000. http://www.duke.law.edu. (accessed August 28, 2008). [ Links ]

World Business Council for Sustainable Development. http://www.wbcsd.org/templates/ TemplateWBCSD1/layout.asp?type=p&MenuId=MzI3&doOpen=1&ClickMenu=LeftM enu (accessed August 28, 2008) [ Links ]

RESULTS OF FIELD RESEARCH

by Diana Jaramillo Piedrahía in 2007

Interview with Bibiana Constam Epinayü, Rector of Centro Étnico-Educativo Kamusüchiwo'u, in Uribia, May 24, 2007. [ Links ]

Interview with Mari Cruz Pushaina, civil servant Secretaría de Asuntos Indígenas, Gobernación de La Guajira, in Riohacha, June 12, 2007. [ Links ]

Interview with Nora Jiménez, coordinator Plan de Ayuda Integral a las Comunidades Indígenas PAICI, Fundación Cerrejón, in Riohacha, June 18, 2007. [ Links ]

Interview with Armando Pérez Araújo. Attorney, Indigenous Communities. Member Organización Yanama, in Riohacha, August 10, 2007. [ Links ]

Presentación Básica de la Fundación Cerrejón. Document in electronic form. Received from: Nora Jiménez, Fundación Cerrejón. [ Links ]

Presentación PAICI. Document in electronic form. Received from: Ricardo González, Oficinas de Comunidades y Tierra, Carbones del Cerrejón LLC. [ Links ]

Resumen PAICI. Document in electronic form. Received from: Nora Jiménez, Fundación Cerrejón. [ Links ]