Services on Demand

Journal

Article

Indicators

-

Cited by SciELO

Cited by SciELO -

Access statistics

Access statistics

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in

SciELO

Similars in

SciELO -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Vniversitas

Print version ISSN 0041-9060

Vniversitas no.131 Bogotá July/Dec. 2015

https://doi.org/10.11144/Javeriana.vj131.vier

VACCINES, INFORMED CONSENT, EFFECTIVE REMEDY AND INTEGRAL REPARATION: AN INTERNATIONAL HUMAN RIGHTS PERSPECTIVE*

VACUNAS, CONSENTIMIENTO INFORMADO, RECURSO EFECTIVO Y REPARACIÓN INTEGRAL: UNA PERSPECTIVA DEL DERECHO INTERNACIONAL DE LOS DERECHOS HUMANOS

Juana I. Acosta**

*Artículo de investigación. I would like to thank Professor Mary Holland for her extraordinary useful guidance and support in developing this project. She has shed light on a vital topic that I truly neglected as a human rights issue. My admiration for her passionate work on this issue and her compassionate closeness with the affected families cannot be described in words. I would also like to thank my husband, whose patience; encouragement, help and advice were indispensable to the completion of this article and my wonderful assistants, Paola Patarroyo and Cindy Espitia, for their hard work.

**LLM in International Legal Studies (Hauser Global Scholar), New York University. Master in Human Rights and Democratization, Universidad Externado de Colombia. Lawyer, Pontificia Universidad Javeriana. Head of the Law Program, Universidad de La Sabana. President of the Colombian Academy of International Law. External advisor to the National Agency of the State's Defense. Contact: juanacl@unisabana.edu.co

Reception date: January 30 th, 2015 Acceptance date: September 18 th, 2015 Available online: November 30th, 2015

To cite this article / Para citar este artículo

Acosta, Juana I., Vaccines, Informed Consent, Effective Remedy and Integral Reparation: an International Human Rights Perspective, 131 Vniversitas, 19-64 (2015). http://dx.doi.org/10.11144/Javeriana.vj131.vier

ABSTRACT

This paper critically addresses the public debate about vaccines' safety and vaccination choice, from a human rights perspective. It proposes a healthy balance between the legitimate goal of public health and the protection of individual rights, and suggests that this balance should be informed by the principles of international human rights law. Part I explains the default premise that informed consent is the general rule for any medical intervention and choice. Considering that compulsory medical interventions violate the right to privacy and the right to physical integrity, their limitation will be legitimate only if the State's compulsory vaccination policy is provided by law, and if strictly necessary and proportional. Part II sets the international standards of an effective remedy that must be provided if a State decides to adopt a compulsory vaccination policy and people are injured as a result of vaccination, even if injuries might be attributable to private conduct. Part III develops the international standards of integral reparation and explains why, if a compulsory vaccination policy is enacted without fulfilling the adequate criteria for the limitation of human rights, the State commits an internationally wrongful act and it has the duty to provide integral reparation.

Keywords: vaccines; informed consent; public health and human rights; Inter-American System of Human Rights; freedom of choice

RESUMEN

Este artículo evalúa críticamente el debate sobre la seguridad de las vacunas y la libertad de elección desde una perspectiva de derechos humanos. Propone un balance entre la salud pública como interés legítimo y la protección de los derechos individuales, y sugiere que este debate debe ser informado por los principios del derecho internacional de los derechos humanos. La sección I explica la premisa básica de que el consentimiento informado es la regla general para cualquier intervención médica y que la libertad de elección frente a la vacunación es un derecho humano. Partiendo de la base de que las intervenciones médicas violan el derecho a la privacidad y la integridad física, la limitación a estos derechos es legítima solo si la política de vacunación del Estado está provista por ley, y es estrictamente necesaria y proporcional. La sección II describe las obligaciones internacionales en relación con los recursos efectivos que un Estado que decide adoptar una política de vacunación debe ofrecer en relación con posibles daños, aun cuando estos sean atribuibles a conductas de particulares. La parte III desarrolla el concepto de reparación integral y explica por qué si una política de vacunación obligatoria es promulgada sin cumplir los criterios para la limitación de derechos humanos, se produce un hecho ilícito internacional y surge un deber de reparar.

Palabras clave: vacunas; consentimiento informado; Salud Pública y Derechos Humanos; Sistema Interamericano de Derechos Humanos; libertad de elección

SUMMARY

Introduction.- I. Informed consent: vaccination choice as a human right.- A. Informed consent to vaccination as a preventive medical treatment.- A. Armed Conflict in Common Article 3.- 1. The UNESCO Declaration of 2005.- 2. The Oviedo Convention of 1997.- B. Public health and human rights restrictions: criteria for the limitation of individual rights. - Il. The right to an effective remedy for vaccination injuries.- III. Compulsory vaccination, injuries and integral reparation.- A. General criteria.- B. Integral reparation due to vaccines injuries. - C. Guiding principles check list. - Conclusion.- Bibliography.

INTRODUCTION

Public debate about vaccines' safety and vaccination choice has been increasing lately in several countries. Human rights activists, scientists, doctors and parents have warned about several unanswered questions regarding vaccine injuries, including the real necessity of compulsory vaccination programs, and the lack of sufficient liability of the pharmaceutical industry.1 At the same time, legitimate reasons have driven the international community and several actors to be concerned about expanding vaccination policies to prevent disease,2 especially in children and not to create an unreasonable fear regarding vaccines risks.3 Ultimately the concern is the same: the well-being of children.4 However, no one would disagree that a healthy and lawful balance must exist between the legitimate goal of public health and the protection of individual rights. Good guidance for protecting that balance is provided by international human rights law, as recognized by the Universal Declaration on Bioethics and Human Rights.5

Despite the fact that vaccination is a widespread preventive medical intervention, there is scientific consensus that a number of vaccines might produce serious injuries6 to some people, and that these two facts create evident competing interests for any Government between public health, individual rights and even the economic interest of some actors; a comprehensive study of the human rights framework for public policies regarding vaccinations has not been done, and it seems that it has been given low priority for the human rights scholarly agenda.

This paper aims precisely to provide a useful international human rights framework to be applied in a case-by-case analysis of compulsory vaccination policies, in order to initiate a responsible scholarly dialogue regarding this important topic. Part I explains the default premise which is that informed consent is the general rule for any medical intervention and that therefore vaccination choice is a human right. Considering that compulsory medical interventions also violates the right to privacy and the right to physical integrity, limitation of these rights will be legitimate only if the State's compulsory vaccination policy is provided by law, and if it is strictly necessary and proportional.

Part II sets forth the international standards of an effective remedy that must be provided if a State decides to adopt a compulsory vaccination policy and people are injured as a result of vaccination. States must be in compliance with all of these standards, even if injuries might be attributable to private conduct. Part III develops the international standards of integral reparation and explains why, if a compulsory vaccination policy is enacted without fulfilling the adequate criteria for the limitation of human rights, the State commits an internationally wrongful act7 and it has the duty to provide integral reparation for the victims. It also presents a proposal for adequate reparation measures regarding vaccine injuries.

Beforehand I would like to clarify that my approach by no means suggests that I am against vaccines. I am not. On the contrary, I believe that vaccines have brought great benefits, and that enhanced immunization programs and plans to control infectious diseases are vital, particularly in developing countries. Nor do I pretend to define the health risks of vaccines, as I am limited by my capacity as a lawyer, and this medical task would be irresponsible. This article intends to give only an initial insight of the international human rights framework that can eventually be applied to the vaccination choice debate. However, I must admit that if there are no sufficient grounds for restricting human rights and especially the right to informed consent, I am a faithful defender of vaccination choice. I am also a faithful defender of vaccination accessibility, particularly for vulnerable populations. However, the question of accessibility of vaccination does not exclude the possibilities of freedom of choice.

Also, in the analysis I will use different human rights standards, some binding and others non-binding. In particular, some of the international instruments and jurisprudence may be binding for some particular States and not for others. Although several arguments could be made to prove that many of the international standards referred to are a part of customary international law, this is not the objective of this piece and I do not argue that every norm or standard is mandatory for every State. However, I do argue that almost every principle stated in the article could be a useful guidance for any State in designing and implementing vaccination public policies. That is my final purpose: to provide useful guidance to address a very difficult debate. Thus, my hope is to start a more serious discussion about how human rights can guide public policies regarding this preventive medical intervention.

I. INFORMED CONSENT: VACCINATION CHOICE AS A HUMAN RIGHT

A. Informed consent to vaccination as a preventive medical treatment

Promoting health involves three levels of prevention: primary prevention or pure prevention (preventing the health problem from occurring at all), secondary prevention (management of the treatment to avoid actual damages to the person's health) and tertiary prevention (to limit the impairment, increase the quality of life and prolong life).8 One clear example of pure prevention treatment is vaccination.9 All medical treatments, including preventive medical treatment, can only be carried out with informed consent, except under very extraordinary circumstances. This rule is developed in international bioethics declarations, human rights instruments and human rights jurisprudence and doctrine.

After World War II, in 1947, the world embraced the Nuremberg Code.10 The first principle of this Code states that the voluntary consent of the human subject in a medical procedure is absolutely essential. The goal was to prohibit experimentation on human subjects without free and informed consent. Since then, several international instruments have protected directly and indirectly the right to free and informed consent for medical and scientific experimentation.11

Particularly important are the Universal Declaration on Bioethics and Human Rights or UNESCO Declaration of 200512 and the Oviedo Declaration of 1997,13 instruments that explicitly develop the right to informed consent in medical interventions.

1. The UNESCO Declaration of 2005

In 2005, the United Nations Education, Scientific, and Cultural Organization (UNESCO), adopted the Universal Declaration on Bioethics and Human Rights (UNESCO Declaration). Article 6 of the Declaration provides that:

(...) Any preventive, diagnostic and therapeutic medical intervention is only to be carried out with the prior, free and informed consent of the person concerned, based on adequate information. The consent should, where appropriate, be express and may be withdrawn by the person concerned at any time and for any reason without disadvantage or prejudice (...) (emphasis added).

The provision means that "no interference in the human body must be undertaken without the permission of the person concerned."14 The legislative history of the UNESCO Declaration does not explain the inclusion of the word preventive in article 6. In fact, articles 6 and 7 were the result of the division and addition of article 10, a provision that initially did not include the word preventive. Thus, this key word was added in the last Declaration discussion in June 2005, without a particular explanation.15 Although some governments16 were of the opinion that informed consent should only be a requisite for particularly invasive treatments, this proposal was not accepted in the final draft.

The Declaration entrusts UNESCO to seek the assistance of the International Bioethics Committee (IBC), as well as the Intergovernmental Bioethics Committee (IGBC), to promote and disseminate the principles set out in the Declaration. In 2008, the IBC issued the Report on Consent (which interprets article 6 and 7 of the Declaration). This Report is perhaps the best document available to analyze and interpret the Declaration's provisions. The Report on length affirms that:

[...] Public health measures, aiming at preventing, eradicating, or alleviating a problem of importance for the whole population or groups within it, might interfere with the self-determination of individuals. Such restrictions on the freedom of people to choose for themselves should be strictly regulated and be in accordance with Article 27 of the Declaration on 'Limitations on the application of principles'. For example, the threat of an epidemic legitimates the public hand to order compulsory measures; a well-known example is the quarantine (...). Today, such threats may lead to ordering the immunization of an entire population or categories within it (e.g. persons employed in the health field). Furthermore, even without epidemic danger, it might be justified to declare immunizations compulsory in order to ensure a sufficient coverage in the population17 (emphasis added).

It seems that the Report considers the possibilities of compulsory vaccination, even without epidemic danger, but always under the limitation principles of article 27 of the UNESCO Declaration.18 These principles, as I will show below, are complemented by the development of the additional principles governing the limitation of rights under international human rights law.

Although the UNESCO Declaration is not a binding document, it is worth mentioning that it was adopted by the acclamation19 of all Member States. It was the United States who urged that acclamation vote:

The United States is pleased to be able to join consensus on the Universal Declaration on Bioethics and Human Rights and urges that it be adopted by acclamation and without amendment. This document helps to provide a basic framework of ethical principles to guide Member States in the development of their domestic legislation and policies20 (emphasis added).

Thus, the principles embodied in the Declaration are undoubtedly very important to the design and implementation of public policies in the field of public health.

2. The Oviedo Convention of 1997

The Council of Europe approved the Convention on Human Rights and Biomedicine (Oviedo Convention) in 1997. Although this Convention is only enforceable for European countries which have signed it, it provides useful guidance for the correct interpretation and application of the principle of informed consent, considering that it is not only a binding international treaty, but also that it sets forth established rules of interpretation in the field. Regarding consent, article 5 of the Convention affirms:

An intervention in the health field may only be carried out after the person concerned has given free and informed consent to it. This person shall beforehand be given appropriate information as to the purpose and nature of the intervention as well as on its consequences and risks. The person concerned may freely withdraw consent at any time.21

The legislative history of the Oviedo Convention is summarized in the Explanatory Report (ER) to the Convention, drawn up under the responsibility of the Secretary General of the Council of Europe, at the request of the Steering Committee on Bioethics (CDBI). This ER takes into account the discussions held in the CDBI and its Working Group entrusted with the drafting of the Convention, as well as the remarks and proposals made by the States' delegations. Although the ER is not an authoritative interpretation of the Convention, it covers the main issues discussed in the preparatory work and provides information to clarify the object and purpose of the Convention and to better understand the scope of its provisions.22Regarding consent, the ER affirms, among other things, that:

Article 5... deals with consent and affirms at the international level an already well-established rule that is that no one may in principle be forced to undergo an intervention without his or her consent. Human beings must therefore be able freely to give or refuse their consent to any intervention involving their person. This rule makes clear patients' autonomy in their relationship with health care professionals and restrains the paternalist approaches which might ignore the wish of the patient. The word "intervention" is understood in its widest sense, as in Article 4 - that is to say, it covers all medical acts, in particular interventions performed for the purpose of preventive care, diagnosis, treatment, rehabilitation or research23 (emphasis added).

The ER also explains that the patient's consent is considered to be free and informed if it is given on the basis of objective information from the responsible health care professional "as to the nature and the potential consequences of the planned intervention or of its alternatives, in the absence of any pressure from anyone"24(emphasis added). According to the ER, information must include (i) the purpose of the treatment, (ii) the nature and consequences of the intervention and (iii) the risks involved (not only the inherent risks but also risks related to the individual characteristics of each patient). Finally, requests for additional information made by patients must be adequately answered.

The European Court of Human Rights has reaffirmed that informed consent is required for any medical intervention under the Oviedo Convention. In M.A.K. and R.K. v. United Kingdom, a case involving, among other things, a blood test of a 9 years old girl without her parent's permission, the Court stated that:

Domestic law and practice clearly requires the consent of either the patient or, if they are incapable of giving consent, a person with appropriate authorization before any medical intervention can take place. Where the patient is a minor, the person with appropriate authorization is the person with parental responsibility. This fully accords with the Council of Europe's Convention on Human Rights and Biomedicine25 (emphasis added).

Thus, the European Court concluded that "the decision to take a blood test and photograph the girl against her parents' express instructions gave rise to an interference with her right to respect for her private life and, in particular, her right to physical integrity."26 The principle of informed consent in medical interventions has also been considered as an important human rights standard by the Inter-American Human Rights System.27

Thus, current international standards require that any medical intervention, including preventive medical treatment, must be accompanied by informed consent. Therefore, vaccination, as a preventive treatment, requires the previous informed consent of any patient. Informed consent includes not only information about the general inherent risks of vaccines, but also information of risks related to the individual characteristics of each patient. This does not mean that compulsory vaccination programs are completely prohibited. However, it means that if a compulsory vaccination program is established, the legislature must determine that the criteria for the limitation of individual rights are fulfilled, considering that by its face, a compulsory vaccination policy limits the right to informed consent, the right to privacy and the right to physical integrity.

B. Public health and human rights restrictions: criteria for the limitation of individual rights

Considering that potential benefits and burdens on human rights may occur in the pursuit of the major purposes of public health,28 a human rights framework provides a useful approach for analyzing and responding to public health challenges.29 Under this framework, some authors have even considered that "health policies and programs should be considered discriminatory and burdensome on human rights until proven otherwise."30

As we have seen, medical interventions might particularly restrict human rights such as the right to a private life and the right to physical integrity.31 In addition to the limitation of these rights, the lack of information and the absence of choice of the subject to any medical intervention constitutes a restriction of the right to informed consent. Finally, if injuries result from compulsory medical interventions and redress and compensation are not available, then there might also be a restriction of the right to an effective remedy and the right to integral reparation.32

Public health is of course a legitimate goal of any State. The question is under what circumstances compulsory medical intervention is the proper means to achieve that legitimate aim. Article 27 of the UNESCO Declaration affirms that:

If the application of the principles of this Declaration is to be limited, it should be by law, including laws in the interests of public safety, for the investigation, detection and prosecution of criminal offences, for the protection of public health or for the protection of the rights andfreedoms of others. Any such law needs to be consistent with international human rights law (emphasis added).

Thus, to answer the question of legitimate limitations to the Declaration, review of international human rights law must be taken. International human rights courts have developed a test to analyze if measures restricting the rights of human beings are legitimate and lawful. This test studies whether the measure is provided by law, and whether it was strictly necessary and proportional.33In principle, the State that is adopting or supporting the measure bears the burden of proof.34

Legitimate goal. As affirmed above, public health is a legitimate goal. However, as Lawrence Gostin and Jonathan M. Mann affirm, the Government has the responsibility to articulate the public health purpose as clearly as possible.35 Only clearly articulated goals would help to "identify the true purpose of intervention, facilitate public understanding and debate around legitimate health purposes, and reveal prejudice, stereotypical attitudes, or irrational fear."36 For instance, a compulsory vaccination policy, which restricts informed consent, personal integrity and the right to privacy, would have to be articulated under a clear purpose, such as the eradication of a specific epidemic, and not just generally for the prevention of disease. Also, a clearly articulated goal assists with the analysis of the legitimacy of the purpose of the policy.

Provided by law. As the Inter-American Court of Human Rights has affirmed, the word law for the legitimate restriction of rights "means a general legal norm tied to the general welfare, passed by democratically elected legislative bodies established by the Constitution, and formulated according to the procedures set forth by the constitutions of the States Parties for that purpose."37 In a very eloquent way the Court explains that:

In order to guarantee human rights, it is therefore essential that state actions affecting basic rights not be left to the discretion of the government but, rather, that they be surrounded by a set of guarantees designed to ensure that the inviolable attributes of the individual not be impaired. Perhaps the most important of these guarantees is that restrictions to basic rights only be established by a law passed by the Legislature in accordance with the Constitution. Such a procedure not only clothes these acts with the assent of the people through its representatives, but also allows minority groups to express their disagreement, propose different initiatives, participate in the shaping of the political will, or influence public opinion so as to prevent the majority from acting arbitrarily. Although it is true that this procedure does not always prevent a law passed by the Legislature from being in violation of human rights —a possibility that underlines the need for some system of subsequent control— there can be no doubt that it is an important obstacle to the arbitrary exercise of power38(emphasis added).

Also, the meaning of the word laws "must be sought as a term used in an international treaty. It is not, consequently, a question of determining the meaning of the word laws within the context of the domestic law of a State Party."39 Thus, an executive decree, for instance, would not be in compliance with this requirement.

Strict necessity. When a State invokes reasons of general interest or public welfare to limit human rights, those reasons "will be subjected to an interpretation strictly limited to 'just demands' of a 'democratic society' that takes into account the balance between the different interests at stake40 and the existence of a truly compelling public interest."41 According to the European Court of Human Rights, this test requires that States prove the existence of a "pressing social need."42

The strict necessity element must also be analyzed according to available alternatives.43 In other words, the measures must be the least restrictive alternative to achieve the public health objective.44Noncoercive approaches should always be considered first.45 Thus, there is a need to show that a less restrictive alternative is not feasible. In an epidemic, for instance, an alternative to compulsory vaccination could be quarantine. Both measures restrict human rights in different degrees, but informed consent could be protected by the opportunity to choose between the alternatives, with full information about the possible risks.

Proportionality. The measure must be proportional to the legitimate aim.46 In evaluating proportionality, the legislature must consider the individual risk posed by each individual case. In order to restrict human rights, a coercive approach might be sustained only when there is an "individual determination that the person poses a significant risk to the public."47 The risk to the public must be probable and not merely speculative or remote.48 The possible harm must also be substantial.49

The European Court of Human Rights has affirmed that all limitations must entail a reasonable relation of proportionality between the means employed and the aim sought.50 Also, proportionality implies the balance between the interests of the community and the protection of individual rights.51 Moreover, the Inter-American Court has affirmed that "there is a need to look behind the mere appearances, in order to ascertain the real situation behind the reported situation."52 For instance, the legislature should investigate the existence of a real risk for the population behind the compulsory vaccination policy, and not a private economic interest or other illegitimate interest.53

Thus, before establishing a compulsory vaccination policy, any State must first test every measure adopted under the above criteria. This is a necessary process in order to protect an adequate balance between public health and individual rights.

II. THE RIGHT TO AN EFFECTIVE REMEDY FOR VACCINATION INJURIES

If a State decides to adopt a compulsory vaccination policy and people are injured as a result of vaccination, the State has a duty to provide an effective remedy54 for victims. Moreover, if the criteria for a lawful limitation of rights were not fulfilled and information was not available, the remedy must be provided not only for the injury, but also for a violation of the right to privacy, the right to physical integrity and the right to informed consent. The guarantee of an effective remedy "constitutes one of the basic pillars (...) of the rule of law in a democratic society."55 The indisputable universality of this right is evidenced by its recognition by the most important universal and regional international human rights instruments, as follows.

Article 8 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights provides that "Everyone has the right to an effective remedy by the competent national tribunals for acts violating the fundamental rights granted him by the Constitution or by law."

Article 2 of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights provides that:

every State must ensure: (a) that any person whose rights or freedoms as herein recognized are violated shall have an effective remedy, notwithstanding that the violation has been committed by persons acting in an official capacity; (b) that any person claiming such a remedy shall have his right thereto determined by competent judicial, administrative or legislative authorities, or by any other competent authority providedfor by the legal system of the State, and to develop the possibilities ofjudicial remedy, and (c) that the competent authorities shall enforce such remedies when granted.

The three most important regional human rights systems also recognize the protection of an effective remedy. Article 13 of the European Convention for the Protection of Human Rights and Fundamental Freedoms provides that "Everyone whose rights and freedoms as set forth in this Convention are violated shall have an effective remedy before a national authority notwithstanding that the violation has been committed by persons acting in an official capacity."56 Article XVIII of the American Declaration on the Rights and Duties of Man provides that "Every person may resort to the courts to ensure respect for his legal rights. There should likewise be available to him a simple, brief procedure whereby the courts will protect him from acts of authority that, to his prejudice, violate any fundamental constitutional rights."57

Article 25 of the American Convention on Human Rights provides that:

1. Everyone has the right to simple and prompt recourse, or any other effective recourse, to a competent court or tribunal for protection against acts that violate his fundamental rights recognized by the constitution or laws of the State concerned or by this Convention, even though such violation may have been committed by persons acting in the course of their official duties. 2. The States Parties undertake: a. to ensure that any person claiming such remedy shall have his rights determined by the competent authority providedfor by the legal system of the state; b. to develop the possibilities of judicial remedy; and c. to ensure that the competent authorities shall enforce such remedies when granted.

Finally, article 7 of the African Charter of Human and People's Rights58 provides that:

1. Every individual shall have the right to have his cause heard. This comprises: (a) the right to an appeal to competent national organs against acts of violating his fundamental rights as recognized and guaranteed by conventions, laws, regulations and customs in force; (b) the right to be presumed innocent until proved guilty by a competent court or tribunal; (c) the right to defense, including the right to be defended by counsel of his choice; (d) the right to be tried within a reasonable time by an impartial court or tribunal (...)

Human Rights tribunals and organs have developed a detailed jurisprudence and doctrine that sets forth the international standards for the guarantee of the right to an effective remedy. This right implies the obligation of States to provide simple, prompt, and effective remedies against violations of human rights. Amongst the most important international human rights standards for guaranteeing an effective remedy we find that:

A. States must have a simple and prompt recourse "in particular of a judicial nature, although other recourses are admissible provided they are effective for the protection of fundamental rights."59

1. The recourse must be effective.60 The effectiveness of a remedy has two aspects: one normative (formal requirements of the remedy), and one empirical (how the remedy works in practice).

a. Normative aspect - Recourse must be suitable: this aspect is evaluated by the recourse potential "to determine whether a violation of human rights had been committed and do whatever it takes to solve it," and its capacity to "yield positive results or responses to human rights violations."61Also, it is not enough that the recourse exists formally, the remedy should also offer the possibility to address human rights violations and to provide adequate redress for such violations.62 This last standard includes:63

- The possibility of verifying the existence of such violation (analysis must get to the merits and the decision must be supported in sufficient legal grounds).

- The possibility of remedying human rights violations,64 and

- The possibility of making reparation for the damage done and of punishing those responsible.

b. Empirical aspect - strict effectiveness: in practice, to fulfill the standard, the recourse must "produce the result for which it was designed."65 A remedy is not effective when:

- It is illusory, when practice has shown its ineffectiveness, when judiciary lacks independency, or when the victim is denied access to a judicial remedy.

- It is excessively onerous for the victim

- The State has not ensured its enforcement by the judicial authorities.

- There is an "inability of victims to obtain compensation."66 On this same issue the European Court of Human Rights has affirmed that there is a human rights violation where victims do not have access to redress to obtain compensation for any damage caused.67

2. The victim of the violation must be able to invoke it.68

3. The State must ensure that the recourse will be heard.69

4. Such recourse must be available not only against violations committed by public officials, but also by violations committed by private persons.70

5. The State must develop the possibilities of judicial remedy.71

6. State authorities must enforce the remedy when granted.72

One very important aspect of the standards of judicial protection for the Inter-American System is that judicial recourses to remedy human rights violations must also comply with the minimum due process guarantees set forth in article 8 of the American Convention.73 The Inter-American Commission and Court have stated that due process elements apply not only to criminal procedures, but also to any judicial procedure, and even administrative procedures,74 and in any other procedure whose decisions may affect the rights of persons.75

Also, article XVIII of the American Declaration of the Rights and Duties of Man is not confined to criminal procedures.76 According to the Inter-American Commission this right is not confined to persons accused of crimes, and is applicable to administrative procedures.77

Thus, any judicial or administrative procedure must respect the minimum guarantees of due process. These minimum guarantees include, amongst others, that the review allowed with remedies must always be "thorough and comprehensive;"78 that cases must be decided in a reasonable time;79 and that judges must be competent, independent80 and impartial.81

Also, every administrative decision must be subject to some form of judicial control that allows the State to determine whether it respects the minimum human rights guarantees.82 This control is more essential when domestic administrative bodies "have broad powers" that could be used, without adequate control, to favor particular or partisan objectives.83

Regarding accountability of medical professionals, the European Court has affirmed that in public health issues States have a positive obligation to make regulations that compel hospitals, whether private or public, to adopt appropriate measures for the protection of patients' lives.84 To enforce positive obligations in public health, recourse to criminal law provisions could be required. However the Court has affirmed that:

The obligation may for instance also be satisfied if the legal system affords victims a remedy in the civil courts, either alone or in conjunction with a remedy in the criminal courts, enabling any liability of the doctors concerned to be established and any appropriate civil redress, such as an order for damages and for the publication of the decision, to be obtained. Disciplinary measures may also be envisaged.85

Hence, higher and stricter international human rights standards have been developed regarding the right to an effective remedy. States must be in compliance with all of these standards, even if conduct might be attributable to a private actor, because the State has to provide an effective remedy, even if it is the private entity that is called to provide for an integral reparation.

III. COMPULSORY VACCINATION, INJURIES AND INTEGRAL REPARATION

It is a recognized norm of customary international law86 that "all violations of human rights entail the right to redress and reparation."87 Although the European Human Rights System has been important in the development of the concept of integral reparation, the Inter-American Human Rights System has built a true doctrine on reparations,88 which goes far beyond the simple reiteration of the traditional compensation measures.

A. General criteria

For the establishment of reparations, the Inter-American Human Rights System has developed the following general criteria:89

- The reparation of harm caused by a violation requires, whenever possible, full restitution (restitutio in integrum), which consists of restoring the situation that existed before the violation occurred.90

- When restitution in integrum is not possible, the State must adopt a series of measures that, in addition to guaranteeing respect for the rights violated, will ensure that the damage resulting from the infractions is repaired, by way, inter alia, of payment of an indemnity as compensation for the harm caused.91

- The obligation to provide reparations, which is regulated in all its aspects (scope, nature, modalities, and designation of beneficiaries) by international law, cannot be altered or eluded by the State's invocation of provisions of its domestic law.92

- Reparations consist in those measures necessary to make the effects of the committed violations disappear. The nature and amount of the reparations depend on the harm caused at both the material and moral levels. Reparations cannot, in any case, entail either the enrichment or the impoverishment of the victim or his or her family,93 and

- The specific method of reparation varies according to the damage caused. "It may be restitutio in integrum of the violated rights, medical treatment to restore the injured person to physical health, an obligation on the part of the State to nullify certain administrative measures, restoration of the good name or honor that were stolen, payment of an indemnity, and so on."94

Thus, the System has developed a doctrine of reparations according to the different damages: pecuniary damage, non pecuniary damage, damage to the family state95 and damage to the life plan.96 These damages are restored not only by compensation, but also by satisfaction measures and guarantees of non-repetition (which may be described as "a positive reinforcement of future performance."97) Regarding the non-pecuniary damage, for instance, the Court has affirmed that:

Non-pecuniary damage can include the suffering and hardship caused to the direct victims and to their next of kin, the harm of objects of value that are very significant to the individual, and also changes, of a non-pecuniary nature, in the living conditions of the victims. Since it is not possible to allocate a precise monetary equivalent to non-pecuniary damage, it can only be compensated in two ways in order to make integral reparation to the victims. First, by the payment of a sum of money that the Court decides by the reasonable exercise of judicial discretion and in terms of fairness. Second, by performing acts or implementing projects with public recognition or repercussion, such as broadcasting a message that officially condemns the human rights violations in question and makes a commitment to efforts designed to ensure that it does not happen again. Such acts have the effect of restoring the memory of the victims, acknowledging their dignity, and consoling their next of kin98 (emphasis added).

Particularly interesting in our case, is the damage to the life plan, explained by the Inter-American Court in Loayza Tamayo v. Peru, a case concerning unlawful deprivation of liberty, torture, cruel and inhuman treatment, violation of the judicial guarantees, and double jeopardy to María Elena Loayza-Tamayo. The Court affirmed that:

The concept of a "life plan" is akin to the concept of personal fulfillment, which in turn is based on the options that an individual may have for leading his life and achieving the goal that he sets for himself. Strictly speaking, those options are the manifestation and guarantee of freedom. An individual can hardly be described as truly free if he does not have options to pursue in life and to carry that life to its natural conclusion. Those options, in themselves, have an important existential value. Hence, their elimination or curtailment objectively abridges freedom and constitutes the loss of a valuable asset, a loss that this Court cannot disregard.

(...)

In other words, the damage to the "life plan", understood as an expectation that is both reasonable and attainable in practice, implies the loss or severe diminution, in a manner that is irreparable or reparable only with great difficulty, of a person's prospects of self-development. Thus, a person's life is altered by factors that, although extraneous to him, are unfairly and arbitrarily thrust upon him, in violation of laws in effect and in a breach of the trust that the person had in government organs duty-bound to protect him and to provide him with the security needed to exercise his rights and to satisfy his legitimate interests99 (emphasis added).

Accordingly, damages must be restored not only by monetary compensation, but also by what the Court calls "measures of satisfaction, rehabilitation and guarantees of non-repetition."100 Some of the most common measures of satisfaction ordered by the Inter-American System are the publication of judgments,101 a ceremony for the public acknowledgment of international responsibility,102 measures to commemorate and render homage to the victims,103 erect appropriate and proper monuments104 and provide scholarship funds.105

Especially important for the Inter-American System are the rehabilitation measures. The Court has ordered on many occasions medical and psychological care for the victims, including also adequate medical or psychological care for the next of kin.106 The treatment is very broad. For example, in the Pueblo Bello case the Court ordered the following:

the Court orders the State to provide, free of charge and through the national health service, the appropriate treatment these persons require, after they have given their consent (.) This treatment must be provided for the necessary time and include medication. In the case of psychological care, the specific circumstances and needs of each person should be considered, so that they are provided with collective, family or individual treatment, as agreed with each of them and following individual assessment107 (emphasis added).

In addition, guarantees of non-repetition have included the modification of legislation108 (even the modification of national constitutions109), human rights courses for public officials, and many others. Particularly relevant to our analysis is one guarantee of non-repetition ordered by the Court in the case of Albán-Cornejo v. Ecuador,110 a case concerning medical malpractice in a private health institution. In this case, the Court ordered a campaign for the rights of patients and education and training of those in charge of the administration of justice, as follows:

The Court acknowledges that the State has adopted different domestic measures to regulate the rendering of health care services by public and private centers, and to foster the observance of patients' rights, which will make it possible to improve health care, as well as its regulation and supervision. Within a reasonable time, the State shall widely disseminate patients' rights, using proper means of communication and applying both existing Ecuadorian legislation and international standards (...) The Court also deems it necessary that, within a reasonable time, the State implement an education and training program for justice operators111 and health care professionals about the laws enacted by Ecuador in relation to patients' rights and to the punishment for violating them112 (emphasis added).

Finally, the Court ordered a full investigation, prosecution and eventual punishment of those individually responsible for the violations. These measures respond in particular to the right to truth. Although international human rights treaties do not explicitly provide for a right to know the truth, "such a right may be considered to arise from the States' conventional duty to ensure human rights."113 According to the Inter-American Court, knowing the truth benefits not only the victims, the next of kin of the victims and society but also prevents violations occurring again in the future. In a very eloquent manner, the Final Report of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Sierra Leone affirms that:

The right to truth is inalienable. This right should be upheld in terms of national and international law. It is the reaching of the wider truth through broad-based participation that permits a nation to examine itself and to take effective measures to prevent a repetition of the past.114

B. Integral reparation due to vaccines injuries

If a State adopts a compulsory vaccination policy without adequately fulfilling the criteria for the limitation of human rights, the State commits an internationally wrongful act115 and it has the duty to provide integral reparation for the victims. Note that a different treatment will be needed if: (i) the State has fulfilled all the criteria and injuries have nonetheless occurred; or (ii) the State has implemented a vaccination policy based on free and informed consent with adequate information available for patients, and injuries occur. In these last two scenarios, a State might not be obliged to compensate, or at least its obligation to compensate would not be the consequence of an internationally wrongful act, but, for instance, as part of a public policy designed by the State to compensate these injuries.

Damages for injury from a vaccine as a consequence of an internationally wrongful act might include pecuniary damage, non-pecuniary damage and damage to the life plan. If this is so, some of the reparation measures that could be adopted by any State are:

- Provide adequate compensation for pecuniary and non-pecuniary damages.

- Provide adequate measures of satisfaction such as public acknowledgment of responsibility and symbolic measures recognizing the dignity of the victims.

- Provide adequate rehabilitation of the victims for the necessary time including medication and psychological care, and

- Provide guarantees of non-repetition that might include, according to the specific facts of each case:

- Proper funding for research on vaccine safety, for instance in cases in which the injury occurred because of a lack of research of vaccination health risks.

- Modification of legislation that obstructs the right to adequate redress, or enactment of legislation that provides for an effective remedy, as appropriate.

- The investigation of eventual criminal or administrative responsibility of public officials or private companies (e.g. the pharmaceutical industry).

- The implementation of an education and training programme for law enforcement officials, justice administration officials and health care professionals, and

- The establishment of a Truth Commission regarding vaccine safety, vaccine injuries, vaccine components and the like. This measure could be particularly useful in cases in which non-disclosure regarding vaccine injuries has been a general pattern among health professionals, scientists and even victims.

The degree and nature of each reparation measure depends on the cause and nature of the injury and the degree in which the State has complied with the criteria for the lawful limitation of human rights. In any case, perhaps the most important measures are the guarantees of non-repetition, because only the right to truth (especially regarding vaccine safety), is able to prevent future violations, and this is the ultimate goal that should concern all States.

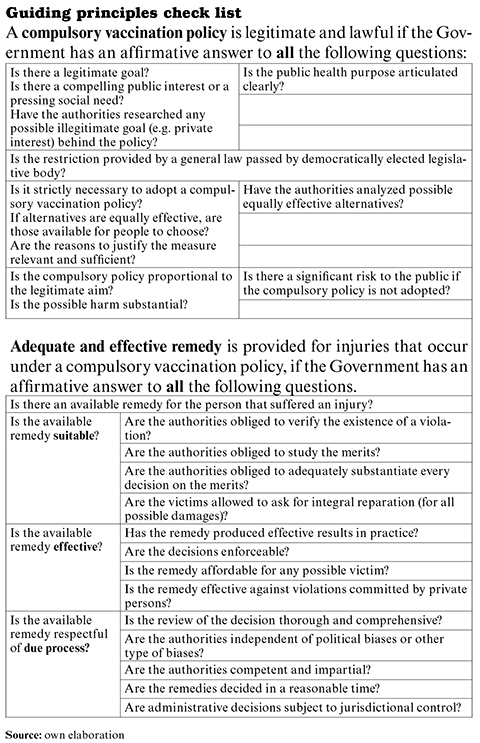

C. Guiding principles check list

The following check list could help those responsible in designing public policies regarding vaccination, to properly apply the principles set forth above.

CONCLUSION

International human rights principles are extremely useful to frame public health policies that might restrict individual rights. In re-designing vaccination policies, States must test every measure. Only those measures that are adopted under clearly articulated legitimate purposes and that are strictly necessary and proportional may overcome the human rights test. If the test for a compulsory vaccination policy is not fulfilled, then freedom of choice should be the rule. Otherwise, the state commits an international wrongful act and is oblige to provide full reparation. Even when the human rights' test is fulfilled, if compulsory policies restrict individual rights and harm human beings, the State has to provide for adequate redress and reparation for injuries.

This analysis must be applied in a case-by-case basis and according to the particular context in each country. Therefore, it is not possible to design a globally applicable compulsory vaccination scheme, considering that risks and vulnerability to epidemics may vary in every country. However, general human rights principles are applicable to all situations and are useful to concretize the measures in particular contexts and situations. This article includes a proposed guiding principles' check list, as a didactic tool that can be extended according to domestic laws and domestic case law.

An adequate balance between public vaccination policies and individual rights is vital for the legitimacy of the measures adopted, the confidence of parents in their children's treatments and the strengthening of a democratic society. Several questions still remain regarding the correct application of a human rights framework to the vaccine safety debate. Yet, instead of promoting confrontational debates, communities should build constructive spaces for an open and transparent dialogue. States have the duty and the right to design and implement public health policies. However, the strongest policies will be built if (i) different points of views are considered; (ii) the decisions are made based on the best possible and adequate research and, above all; (iii) and the respect and promotion of human rights is the desired objective. I hope I have contributed with some guidance to these legitimate purposes.

FOOTNOTES

1Louise Kuo Habakus & Mary Holland, eds., Vaccine Epidemic: How Corporate Greed, Biased Science, and Coercive Government Threaten Our Human Rights, Our Health, and Our Children (Skyhorse Publishing, Inc., New York, 2011). Arthur Allen, Vaccine: the Controversial Story of Medicine's Greatest Lifesaver (WW Norton & Company, New York, 2007). Stephanie Cave & Deborah Mitchell, What Your Doctor May Not Tell You aboutTM Children's Vaccinations (Warner Books, New York, 2001). Robert W. Sears, The Vaccine Book: Making the Right Decision for Your Child (Little, Brown and Company, New York, 2007). Randall Neustaedter, The Vaccine Guide: Risks and Benefits for Children and Adults (2nd ed., North Atlantic Books, Berkeley, 2002). Andreas Moritz, Vaccine-Nation: Poisoning the Population, One Shot at a Time (Ener-Chi Wellness Center, Morris, Illinois, 2011).

2The Committee of Economic, Social and Cultural Rights has affirmed for example that "the control of diseases refers to States' individual and joint efforts to, inter alia, make available relevant technologies, using and improving epidemiological surveillance and data collection on a disaggregated basis, the implementation or enhancement of immunization programs and other strategies of infectious disease control." United Nations, Committee of Economic, Social and Cultural Rights, CESCR, Comment 14: The Right to the Highest Attainable Standard of Health, 16, E/C.12/2000/4 (Nov. 8, 2000). Available at: http://www.ohchr.org/EN/Issues/Education/Training/Compilation/Pages/eGeneralCommentNo14Therighttothehighestat-tainablestandardofhealth(article12)(2000).aspx

3Richard A. Epstein, It Did Happen Here: Fear and Loathing on the Vaccine Trail, 24 Health Affairs, 3, 740-743 (2005). Available at: http://content.healthaffairs.org/content/24/3/740.full.pdf+html. Seth Mnookin, The Panic Virus: A True Story of Medicine, Science, and Fear (Simon & Schuster, New York, 2011). Paul A. Offit, Deadly Choices: How the Anti-Vaccine Movement Threatens Us All (Basic Books, New York, 2011). Paul A. Offit & Charlotte A. Moser, Vaccines & Your Child: Separating Fact from Fiction (Columbia University Press, New York, 2011).

4Louise Kuo Habakus & Mary Holland, eds., Vaccine Epidemic: How Corporate Greed, Biased Science, and Coercive Government Threaten Our Human Rights, Our Health, and Our Children (Skyhorse Publishing, Inc., New York, 2011). Review by Bernadine Healy, M.D., former Director (April 9, 1991-June 30, 1993), National Institute of Health and Current Health Director.

5United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization, UNESCO, Universal Declaration on Bioethics and Human Rights or UNESCO Declaration, General Conference of UNESCO, 33rd session, f 27 (October 19, 2005). Available at: http://portal.unesco.org/en/ev.phpURL_ID=31058&URL_DO=DO_TOPIC&URL_SECTION=201.html. "If the application of the principles of this Declaration is to be limited, it should be by law, including laws in the interests of public safety, for the investigation, detection and prosecution of criminal offences, for the protection of public health or for the protection of the rights and freedoms of others. Any such law needs to be consistent with international human rights law."

6In the United States, for example, the National Childhood Vaccine Injury Act recognizes that some vaccines might generate serious injuries such as anaphylaxis, encephalopathy, chronic arthritis and paralytic polio. United States, National Childhood Vaccine Injury Act of 1986, 42 U.S.C. §§ 300aa-1-34. Available at: https://www.govtrack.us/congress/bills/99/hr5546. See U.S. Government Vaccine Injury Compensation Table in Appendix 4, available at www.hrsa.gov/vaccinecompensation/

7According to Article 2 of the Articles on State Responsibility for Internationally Wrongful Acts, there is an internationally wrongful act of a State when: "a) Conduct consisting of an action or omission is attributable to the State under international law; and (b) That conduct constitutes a breach of an international obligation of the State." United Nations, General Assembly, State Responsibility for Internationally Wrongful Acts, G.A. Res. 56/83, U.N. GAOR, 56th Session, Supp. No. 10, at 2, UN Doc. A/56/10, in Report of the International Law Commission, 53rd Session, 59-365 (United Nations, New York, 2001). Available at: http://www.un.org/documents/ga/docs/56/a5610.pdf

8International Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies & François-Xavier Ba-gnoud, Center for Health and Human Rights, Public Health: An Introduction, in Health and Human Rights: A Reader, 29-34, 30 (Jonathan M. Mann, Sofia Gruskin, Michael A Grodin & George J. Annas, eds., Routledge, Taylor and Francis Group, New York, London, 1999).

9International Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies & François-Xavier Bagnoud, Center for Health and Human Rights, Public Health: An Introduction, in Health and Human Rights: A Reader, 29-34, 30 (Jonathan M. Mann, Sofia Gruskin, Michael A Grodin & George J. Annas, eds., Routledge, Taylor and Francis Group, New York, London, 1999).

10Nuremberg Code, 1947. Available at: http://www.hhs.gov/ohrp/archive/nurcode.html

11United Nations, General Assembly, Universal Declaration of Human Rights, G.A. Res. 217 (III) A, U.N. Doc. A/Res/217(III), art. 7 (10 December 1948). Available at: http://www.un-documents.net/a3r217a.htm. United Nations International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, adopted and opened for signature, ratification and accession by General Assembly resolution 2200A (XXI) of 16 December 1966, entry into force 23 March 1976, in accordance with Article 49, 999 U.N.T.S. 171. Available at: http://www.ohchr.org/EN/ProfessionalInterest/Pages/CCPR.aspx. The Covenant entered into force in 23 March, 1976, but the provisions of article 41 entered into force 28 March, 1979.

12Universal Declaration on Bioethics and Human Rights, General Conference of UNESCO, 33rd session (October 19, 2005). Available at: http://portal.unesco.org/en/ev.phpURL_ID=31058&URL_DO=DO_TOPIC&URL_SECTION=201.html

13Council of Europe, Convention for the Protection of Human Rights and Dignity of the Human Being with Regard to the Application of Biology and Medicine: Convention on Human Rights and Biomedicine, Oviedo Convention, CETS 164, Oviedo, Apr. 4, 1997. Available at: http://www.coe.int/en/web/conventions/full-list/-/conventions/rms/090000168007cf98

14Regine Kollek, Consent, in The UNESCO Universal Declaration on Bioethics and Human Rights: Background, Principles and Application, Article 6, 123-138 (Henk A. M. J. ten Have & Michèle S. Jean, eds., UNESCO, Paris, 2009). Available at: http://unesdoc.unesco.org/images/0017/001798/179844e.pdf

15I want to thank Doctor Edmund D. Pellegrino, M.D. (member of the International Bioethics Committee at the time the Explanatory Report was drafted), for his guidance on this point. In a generous e-mail he stated that "to my knowledge there was no extensive discussion regarding the inclusion of the word preventive in the UNESCO Committee on Bioethics Declaration. There was especially no specific reference to the word preventive. (...) Nor was there any specific mention of "preventive" in relationship to vaccines. In the Declaration I believe "preventive" was included as a general requirement for informing patients of potential side effects of both therapeutic and preventive measures. This knowledge is necessary in order to obtain valid consent for administering any preventive measure. Preventive as well as therapeutic measures can have harmful as well as beneficial effects." E-mail from Doctor Edmund D. Pellegrino, M.D. member of the International Bioethics Committee at the time the Explanatory Report was drafted, to Juana Inés Acosta, Hauser Scholar at NYU, now Professor at La Sabana University (Apr. 05, 2011 19:34:40 - 0400, received by the NYU server) (on file with author).

16For instance, Saudi Arabia and India. See Intergovernmental Meeting of Experts Aimed at Finalizing a Draft Declaration on Universal Norms on Bioethics, Second Session, Compilation of Proposed Amendments Submitted by Member States, 33-34, UNESCO, SHS/ EST/05/CONF.204/5 (Paris, June 6, 2005). Available at: http://unesdoc.unesco.org/images/0013/001397/139788e.pdf

17International Bioethics Committee, IBC, Report on Consent, SHS/EST/CIB08-09/2008/1 (Paris, 2008). Available at: http://unesdoc.unesco.org/images/0017/001781/178124E.pdf

18For further explanation of these principles, see United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization, UNESCO, Universal Declaration on Bioethics and Human Rights or UNESCO Declaration, General Conference of UNESCO, 33rd session (October 19, 2005). Available at: http://portal.unesco.org/en/ev.phpURL_ID=31058&URL_DO=DO_TOPIC&URL_SECTION=201.html

19This means that it was accepted "by general applause or absence of protest instead of by conducting a vote. The terms is used in the UN alongside 'without a vote' or 'by consensus^". Edmund Jan OsmaBczyk & Anthony Mango, Encyclopedia of the United Nations and International Agreements: T to Z, Vol. 4 (3rd ed., Taylor & Francis, London, New York, 2003).

20United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization, UNESCO, Records of the General Conference, 33rd Session, Annex II: Statements on the Interpretation of Specific Provisions of the Universal Declaration on Bioethics and Human Rights, U.S., 209 (UNESCO, Paris, 2005). Available at http://unesdoc.unesco.org/images/0014/001428/142825e.pdf

21Council of Europe, Convention for the Protection of Human Rights and Dignity of the Human Being with Regard to the Application of Biology and Medicine: Convention on Human Rights and Biomedicine, Oviedo Convention, CETS 164, Oviedo, Apr. 4, 1997, art. 5. Available at: http://www.coe.int/en/web/conventions/full-list/-/conventions/rms/090000168007cf98

22Council of Europe, Explanatory Report to the Convention for the Protection of Human Rights and Dignity of the Human Being with Regard to the Application of Biology and Medicine, Dir/Jur(97)5, 2 (May, 1997). Available at: https://rm.coe.int/CoERMPublicCommonSearchServices/DisplayDCTMContent?documentId=09000016800ccde5

23Council of Europe, Explanatory Report to the Convention for the Protection of Human Rights and Dignity of the Human Being with Regard to the Application of Biology and Medicine, Dir/Jur(97)5, par. 34 (May, 1997). Available at: https://rm.coe.int/CoERMPublicCommonSearchServices/DisplayDCTMContent?documentId=09000016800ccde5

24Council of Europe, Explanatory Report to the Convention for the Protection of Human Rights and Dignity of the Human Being with Regard to the Application of Biology and Medicine, Dir/Jur(97)5, par. 35 (May, 1997). Available at: https://rm.coe.int/CoERMPublicCommonSearchServices/DisplayDCTMContent?documentId=09000016800ccde5

25European Court of Human Rights, ECHR, M.A.K. and R.K. v. United Kingdom, App. No. 45901/05 and 40146/06, f 77 (23 March 2010). Available at: http://hudoc.echr.coe.int/eng?i=001-97880

26European Court of Human Rights, ECHR, M.A.K. and R.K. v. United Kingdom, App. No. 45901/05 and 40146/06, f 77 (23 March 2010). Available at: http://hudoc.echr.coe.int/eng?i=001-97880

27Inter-American Commission of Human Rights, IACHR, María Mamérita Mestanza-Chávez v. Peru, Case 12.191, Report No. 71/2003, OEA/Ser.L/V/II.118 Doc. 70 rev. 2 at 668 (October 22, 2003). Available at: http://www.cidh.org/annualrep/2003eng/Peru.12191.htm. Ms. María Mamérita Mestanza-Chávez suffered from a forced sterilization that ultimately caused her death. In the friendly settlement and according to the Inter-American Commission recommendations, the State made a commitment to "adopt the necessary administrative measures so that that rules established for ensuring respect for the right of informed consent are scrupulously followed by health personnel.")

28Jonathan M. Mann, Lawrence Gostin, Sofia Gruskin, Troyen Brennan, Zita Lazzarini & Harry Fineberg, Health and Human Rights, in Health and Human Rights, 7-20, 12 (Jonathan M. Mann, Sofia Gruskin, Michael A Grodin & George J. Annas, eds., Routledge, Taylor and Francis Group, New York, London, 1999).

29Roberto Andorno, Global Bioethics at UNESCO: In Defence of the Universal Declaration on Bioethics and Human Rights, 33 Journal of Medical Ethics, 3, 150-154. Available at: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2598251/?tool=pubmed

30Jonathan M. Mann, Lawrence Gostin, Sofia Gruskin, Troyen Brennan, Zita Lazzarini & Harry Fineberg, Health and Human Rights, in Health and Human Rights, 7-20, 13 (Jonathan M. Mann, Sofia Gruskin, Michael A Grodin & George J. Annas, eds., Routledge, Taylor and Francis Group, New York, London, 1999).

31European Court of Human Rights, ECHR, Glass v. United Kingdom, App. No. 61827/00, f 70 (9 March 2004). Available at: http://hudoc.echr.coe.int/eng?i=001-61663. This case regarding an imposed treatment on a mentally ill patient without the consent of his parents.

32For a deeper analysis on these rights, see Sections II and III.

33European Court of Human Rights, ECHR, Glass v. United Kingdom, App. No. 61827/00, f 73 (9 March 2004). Available at: http://hudoc.echr.coe.int/eng?i=001-61663. These are the minimal criteria that should be met but some authors have included other additional criteria. See Louise Kuo Habakus &, Mary Holland, eds., Vaccine Epidemic: How Corporate Greed, Biased Science, and Coercive Government Threaten Our Human Rights, Our Health, and Our Children, 20 (Skyhorse Publishing, Inc., New York, 2011). However, I think these additional criteria could be included as part of these general criteria. For example, the limitation of the least intrusive measure is already embraced in the strict necessity requirement, according to human rights jurisprudence.

34This principle can be inferred from ECHR jurisprudence. European Court of Human Rights, ECHR, Glass v. United Kingdom, App. No. 61827/00, f 82 (9 March 2004). Available at: http://hudoc.echr.coe.int/eng?i=001-61663. The Government contended that consent had been given by the applicant, but the Court did not find a persuasive evidence of consent in the Government's response. Thus, the Court found a violation of the Government due to the lack of a "certainty that any consent given was free, expressed and informed." It was easy to infer by the opinion that the burden of proof for that certainty was on the Government. European Court of Human Rights, ECHR, M.A.K. and R.K. v. United Kingdom, App. No. 45901/05 and 40146/06, f 77 (23 March 2010). Available at: http://hudoc.echr.coe.int/eng?i=001-97880. The Court found no justification for the decision to take a blood test and intimate photographs to a nine year old girl against the express wishes of both parents. The Court presumed that the State had to present such justification.

35Lawrence Gostin & Jonathan M. Mann, Toward the Development of a Human Rights Impact Assessment for the Formulation and Evaluation of Public Health Policies, in Health and Human Rights: A Reader, 54-72, 55 (Jonathan M. Mann, Sofia Gruskin, Michael A Grodin & George J. Annas, eds., Routledge, Taylor and Francis Group, New York, London, 1999).

36Lawrence Gostin & Jonathan M. Mann, Toward the Development of a Human Rights Impact Assessment for the Formulation and Evaluation of Public Health Policies, in Health and Human Rights: A Reader, 54-72, 55 (Jonathan M. Mann, Sofia Gruskin, Michael A Grodin & George J. Annas, eds., Routledge, Taylor and Francis Group, New York, London, 1999).

37The Government of Uruguay, by means of communication of August 14, 1985, submitted to the Inter-American Court of Human Rights a request for an advisory opinion on the scope of the word "laws" used in Article 30 (scope of restrictions) of the American Convention on Human Rights. Inter-American Court of Human Rights, IACtHR, Advisory Opinion OC-6/86, The Word "Laws" in Article 30 of the American Convention of Human Rights, Requested by the Government of Uruguay (May 9, 1986). Available at: http://www.corteidh.or.cr/docs/opiniones/seriea_06_ing.pdf. All the English translations of the jurisprudence of the Inter-American Court of Human Rights provided in this paper, are the official translations of the Court.

38Inter-American Court of Human Rights, IACtHR, Advisory Opinion OC-6/86, The Word "Laws" in Article 30 of the American Convention of Human Rights, Requested by the Government of Uruguay, f 22 (May 9, 1986). Available at: http://www.corteidh.or.cr/docs/opiniones/seriea_06_ing.pdf

39Inter-American Court of Human Rights, IACtHR, Advisory Opinion OC-6/86, The Word "Laws" in Article 30 of the American Convention of Human Rights, Requested by the Government of Uruguay, f 19 (May 9, 1986). Available at: http://www.corteidh.or.cr/docs/opiniones/seriea_06_ing.pdf

40Inter-American Court of Human Rights, IACtHR, Salvador Chiriboga v. Ecuador, Preliminary Objections and Merits, Judgment, Serie C No. 179. Manuel Ventura-Robles, Concurring Opinion (May 6, 2008). Available at: http://www.corteidh.or.cr/docs/casos/articulos/seriec_179_ing.pdf. The case concerned and illegitimate restriction to private property in Ecuador.

41Lawrence Gostin & Jonathan M. Mann, Toward the Development of a Human Rights Impact Assessment for the Formulation and Evaluation of Public Health Policies, in Health and Human Rights: A Reader, 54-72, 63 (Jonathan M. Mann, Sofia Gruskin, Michael A Grodin & George J. Annas, eds., Routledge, Taylor and Francis Group, New York, London, 1999).

42European Court of Human Rights, ECHR, Flux v. Moldova, App. No. 22824/04, f 35 (29 July 2008). Available at: http://hudoc.echr.coe.int/eng?i=001-88063. The applicant newspaper alleged, in particular, that its right to freedom of expression had been violated as a result of judicial decisions in defamation proceedings brought against it.

43Lawrence Gostin & Jonathan M. Mann, Toward the Development of a Human Rights Impact Assessment for the Formulation and Evaluation of Public Health Policies, in Health and Human Rights: A Reader, 54-72, 57 (Jonathan M. Mann, Sofia Gruskin, Michael A Grodin & George J. Annas, eds., Routledge, Taylor and Francis Group, New York, London, 1999).

44Lawrence Gostin & Jonathan M. Mann, Toward the Development of a Human Rights Impact Assessment for the Formulation and Evaluation of Public Health Policies, in Health and Human Rights: A Reader, 54-72, 65 (Jonathan M. Mann, Sofia Gruskin, Michael A Grodin & George J. Annas, eds., Routledge, Taylor and Francis Group, New York, London, 1999).

45Lawrence Gostin & Jonathan M. Mann, Toward the Development of a Human Rights Impact Assessment for the Formulation and Evaluation of Public Health Policies, in Health and Human Rights: A Reader, 54-72, 65 (Jonathan M. Mann, Sofia Gruskin, Michael A Grodin & George J. Annas, eds., Routledge, Taylor and Francis Group, New York, London, 1999).

46European Court of Human Rights, ECHR, M.A.K. and R.K. v. United Kingdom, App. No. 45901/05 and 40146/06, f 73 (23 March 2010). Available at: http://hudoc.echr.coe.int/eng?i=001-97880

47Lawrence Gostin & Jonathan M. Mann, Toward the Development of a Human Rights Impact Assessment for the Formulation and Evaluation of Public Health Policies, in Health and Human Rights: A Reader, 54-72, 66 (Jonathan M. Mann, Sofia Gruskin, Michael A Grodin & George J. Annas, eds., Routledge, Taylor and Francis Group, New York, London, 1999).

48Lawrence Gostin & Jonathan M. Mann, Toward the Development of a Human Rights Impact Assessment for the Formulation and Evaluation of Public Health Policies, in Health and Human Rights: A Reader, 54-72, 67 (Jonathan M. Mann, Sofia Gruskin, Michael A Grodin & George J. Annas, eds., Routledge, Taylor and Francis Group, New York, London, 1999).

49Lawrence Gostin & Jonathan M. Mann, Toward the Development of a Human Rights Impact Assessment for the Formulation and Evaluation of Public Health Policies, in Health and Human Rights: A Reader, 54-72, 67 (Jonathan M. Mann, Sofia Gruskin, Michael A Grodin & George J. Annas, eds., Routledge, Taylor and Francis Group, New York, London, 1999).

50European Court of Human Rights, ECHR, Hutten-Czapska v. Poland, App. No. 35014/97, f 167 (19 June 2006). Available at: http://hudoc.echr.coe.int/eng?i=001-75882

51European Court of Human Rights, ECHR, Hutten-Czapska v. Poland, App. No. 35014/97, f 167 (19 June 2006). Available at: http://hudoc.echr.coe.int/eng?i=001-75882. European Court of Human Rights, ECHR, Matos e Silva, Ltda. and others v. Portugal, App. No. 15777/89, f 86 (16 September 1996). Available at: http://hudoc.echr.coe.int/eng?i=001-58063. European Court of Human Rights, Sporrong and Lõnnroth v. Sweden, App. No. 7151/75 and 7152/75, f 69 (23 September 1982). Available at: http://hudoc.echr.coe.int/eng?i=001-57580

52Inter-American Court of Human Rights, IACtHR, Ivcher-Bronstein v. Peru, Merits, Reparations and Costs, Judgment, Serie C No. 74, f 124 (February 6, 2001). Available at: http://www.corteidh.or.cr/docs/casos/articulos/seriec_74_ing.pdf. Considering that there was no evidence or argument to confirm that the precautionary measure ordered by Judge Percy Escobar of Peru was based on reasons of public utility or social interest; to the contrary, the proven facts in this case showed the State's determination to deprive Mr. Baruch Ivcher-Bronstein of the control of Channel 2, by suspending his rights as a shareholder of the Company that owned it. European Court of Human Rights, ECHR, Papamichalopoulos and others v. Greece, App. No. 14556/89, f 42 (24 June 1993). Available at: http://hudoc.echr.coe.int/eng?i=001-57836

53sup>Several authors have affirmed that behind some compulsory vaccination programs the real interest is an economic private interest of the pharmaceutical industry. See generally, Lisa Reagan, A Dragon by the Tail, The Corrupt World of Global Vaccine Politics (Byron Publications, eds., Mullumbimby, Australia, 2005). Available at: http://whale.to/vaccines/reagan. html. Committee on Government Reform, U.S. House of Representatives, Conflicts of Interest in Vaccine Policy Making, Majority Staff Report (2000). Available at National Vaccine Information Center, NVIC: http://www.nvic.org/nvic-archives/conflicts-of-interest.aspx. Although I am not saying these allegations are true, at least these allegations must be analyzed and researched by the legislature before establishing compulsory vaccination policies.

54The expression "effective remedy" is embodied in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (article 8). The American Convention on Human Rights embodies this same rights as the right to an "effective recourse" (article 25).

55Inter-American Court of Human Rights, IACtHR, Tibi v. Ecuador, Preliminary objections, Merits, Reparations and Costs, Judgment, Serie C No. 114, f 131 (September 7, 2004). Available at: http://www.corteidh.or.cr/docs/casos/articulos/seriec_114_ing.pdf. Inter-American Court of Human Rights, IACtHR, 19 Merchants v. Colombia, Merits, Reparations and Costs, Judgment, Serie C No. 109, f 193 (July 5, 2004). Available at: http://www.corteidh.or.cr/docs/casos/artic-ulos/seriec_109_ing.pdf. Inter-American Court of Human Rights, IACtHR, Maritza Urrutia v. Guatemala, Merits, Reparations and Costs, Judgment, Serie C No. 103, f 117 (November 27, 2003). Available at: http://www.corteidh.or.cr/docs/casos/articulos/seriec_103_ing.pdf

56European Court of Human Rights & Council of Europe, European Convention on Human Rights or European Convention for the Protection of Human Rights and Fundamental Freedoms, as amended by Protocols Nos. 11 and 14, supplemented by Protocols Nos. 1, 4, 6, 7, 12 and 13, Rome, 4 November 1950. Available at: http://www.echr.coe.int/Documents/Convention_ENG.pdf

57Organization of American States, OAS, American Declaration on the Rights and Duties of Man, adopted by the Ninth International Conference of American States, Bogotá, Colombia, 1948. Available at: http://cidh.oas.org/Basicos/English/Basic2.American%20Declaration.htm

58Organization of African Unity, African Charter of Human and People's Rights or Banjul Charter, adopted 27 June 1981, OAU Doc. CAB/LEG/67/3 rev. 5, 21 I.L.M. 58 (1982), entered into force 21 October 1986, Banjul, Gambia, 1987. Available at: http://www.achpr.org/instruments/achpr/

59Inter-American Commission of Human Rights, Access to Justice as a Guarantee of Economic, Social, and Cultural Rights. A Review of the Standards Adopted by the Inter-American System ofHuman Rights, Special Report OEA/Ser.L/V/II.129, f 241 (7 September, 2007) (hereinafter, Access to Justice Special Report). Available at: http://www.cidh.org/pdf files/ACCESS TO JUSTICE DESC.pdf

60European Court of Human Rights, ECHR, McFarlane v. Ireland, App. No. 31333/06, f 107 (10 September 2010). Available at: http://hudoc.echr.coe.int/eng?i=001-100413. European Court of Human Rights, ECHR, A, Band Cv. Ireland, App. No. 25579/05 (16 December 2010). Available at: http://hudoc.echr.coe.int/eng?i=001-102332. European Court of Human Rights, ECHR, Stoichkov v. Bulgaria, App. No. 9808/02, f 66 (24 March 2005). Available at: http://hudoc.echr.coe.int/eng?i=001-68625. European Court of Human Rights, ECHR, Vachev v. Bulgaria, App. No. 42987/98, f 71 (8 July 2004). Available at: http://hudoc.echr.coe.int/eng?i=001-61877

61Inter-American Court of Human Rights, IACtHR, Velásquez-Rodríguez v. Honduras, Merits, Judgment, Serie C No. 4, f 66 (July 29, 1988). Available at: http://www.corteidh.or.cr/docs/ casos/articulos/seriec_04_ing.pdf. Inter-American Court of Human Rights, IACtHR, Juan Humberto Sánchez v. Honduras, Preliminary Objections, Merits, Reparations and Costs, Judgment, Serie C No. 99, f 67 (June 7, 2003). Available at: http://www.corteidh.or.cr/docs/casos/articulos/seriec_99_ing.pdf

62Inter-American Court of Human Rights, IACtHR, Velásquez-Rodríguez v. Honduras, Merits, Judgment, Serie C No. 4, f 66 (July 29, 1988). Available at: http://www.corteidh.or.cr/docs/casos/articulos/seriec_04_ing.pdf