Services on Demand

Journal

Article

Indicators

-

Cited by SciELO

Cited by SciELO -

Access statistics

Access statistics

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in

SciELO

Similars in

SciELO -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Revista de la Facultad de Medicina

Print version ISSN 0120-0011

rev.fac.med. vol.60 no.3 Bogotá Sept./Dec. 2012

Original Research

Treatment adherence of hypertensive patients' being attended by Assbasalud ESE, Manizales (Colombia) 2011

José Jaime Castaño-Castrillón1, Christian Echeverri-Rubio2, José Fernando Giraldo-Cardona3, Ángelo Maldonado-Mora2, Jonathan Melo-Parra2, Germán Andrés Meza-Orozco2, Christian Germán Montenegro-Gutiérrez2, Camilo Andrés Peláez-Ramos2, Jader Mauricio Perdomo-Muñoz2, Edwin Andrés Rodríguez-Arias2

1 Fis, MSc. Profesor Titular, Director Centro de Investigaciones, Facultad de Ciencias de la Salud, Universidad de Manizales

2 Estudiante X semestre, Programa de Medicina, Facultad Ciencias de la Salud, Universidad de Manizales, Manizales, Caldas, Colombia.

3 MD, Mag. Docente Semiología, Programa de Medicina, Universidad de Manizales, Manizales Colombia.

Correspondencia: cim@umanizales.edu.co

Summary

Background. Difficulties regarding patient adherence when treating hypertension could be extremely serious as one is dealing with an asymptomatic hypertensive disease.

Objective. Studying adherence to treatment concerning hypertensive patients being attended in Manizales, Colombia, by the state-run Assbasalud programme in 2011.

Materials and Methods. This was a cross-sectional study involving a population of 200 hypertensive people (73.5% were female, average age was 63.76 years) being attended by the state-run Assbasalud ESE, Manizales, during the second half of 2011. The Martín-Bayarre-Grau (MBG) and Morisky-Green (MG) questionnaires were used for evaluating the social support network, as well as the Medical Outcomes Study (MOS) questionnaire.

Results.45% of patients were totally adherent according to MG and 51% totally adherent according to MBG. Regarding the MOS questionnaire, 12.29 people on average were in a patient's social support network, 74.83% received emotional support, 80.45% material aid, 78.61% were involved in leisure and entertainment-related activities, 83.28% were receiving affective support and enalapril was the drug most used in treatment (17.9%), followed by verapamil (10.1%). According to the MBG questionnaire, adherence significantly depended on variables such as education (p=0.000), knowledge about the disease (p=0.032) and MOS social support questionnaire results (p=0.000). The MG questionnaire revealed very few significant relationships for treatment adherence.

Conclusion. The study revealed low adherence levels associated with having a low educational level, poor knowledge regarding the disease and poor social support, thereby making it necessary that Assbasalud ESE take more effective action, especially through its healthcare personnel. The MBG questionnaire had greater consistency regarding a description of adherence than the MG questionnaire.

Keywords: hypertension, medication adherence, public health, chronic disease.

Introduction

Arterial hypertension (AHT) may be considered a variable increasing mechanical and neurohumoral load on the cardiovascular system (1); it is the most frequent chronic disease around the world (2) since a third of the adult population in developed countries has high blood pressure levels/figures, and a worldwide 26% prevalence has been reported (3), without taking pre-hypertension into account as this would obviously raise such figures. It has been estimated that 60% of the adult population will suffer from this disease by 2025 (4). AHT prevalence in Colombia was 12.3% in 1999, according to the second Colombian chronic disease risk factor study (EstudioNacional de Factores de Riesgo de EnfermedadesCronicas - ENFREC 2) (5). This disease's prevalence and incidence in Colombia is currently not known with certainty since few studies have been carried out in this area.

The Seventh Report of the Joint National Committee on Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Pressure (JNC 7) (6) classified normal blood pressure as being less than or equal to 120/80 mmHg, pre-hypertension up to 139/89 mmHg, hypertension grade I having systolic pressure between 140-159 mmHg and diastolic pressure 90-99 mmHg, and hypertension grade 2 greater than 160/100 mmHg.

The onset of AHT depends on an interaction between genetic predisposition (family background) and environmental factors (7) such as food/eating background, psychosocial background, weight change (body weight), dyslipidaemia, smoking, diabetes mellitus (DM), nephropathies, cardiopathy (8), high uric acid levels (9) or preeclampsia (10).

AHT is a disease which is clearly related as the main independent and modifiable risk factor for heart failure, acute myocardial infarction (AMI), cerebrovascular disease, chronic renal failure (11), retinopathy, cognitive impairment and peripheral atherosclerosis (6,12), thereby providing a more than sufficient reason for implementing measures aimed at early detection, improving suitable treatment and preventing damage to targeted organs, thereby ensuring that an ever increasing number of patients become suitably controlled (12). This would lead to reducing morbimortality caused by this disease and its complications. The approach to this disease's treatment must thus be multidisciplinary, arising from a successful doctor-patient relationship understood as being an interaction aimed at restoring a patient's health, preventing diseases and alleviating suffering (13) through good adherence to pharmacological and non-pharmacological treatment.

Treatment adherence is defined as being the effective and committed collaboration of healthcare providers, patients and their families which should lead to optimum and effective results in managing AHT, more than just simple passive compliance with indications given by healthcare personnel (14) and thus avoiding abandonment of treatment and attending programed/scheduled control appointments (15).

The factors intervening in adherence would involve knowledge of the disease and the drugs being prescribed (16,17), a patient's emotional state and marital status (18) positively influencing married patients' adverse reactions to drugs (19) as a reason for abandoning them, self-care agency (20) as personal and characteristic determinant facilitating decision-making and taking action for improving a patient's health, economic and social factors, the severity of the disease and comorbidities and healthcare personnel (perhaps one of the main key factors) (21).

It is reasonable to consider that adherence does not just refer to pharmacological treatment, since being careful with one's diet, exercise and modifiable factors (22) also influence depending on suitable compliance to some degree.

Lack of treatment adherence regarding chronic disease is currently considered a real public health problem (23); knowledge regarding knowing about, managing and preventing hypertensive disease must be gone into more deeply and provides the main motive for implementing healthcare campaigns and schemes aimed at early detection and improvement of treatment through ensuring adherence. This would avoid increased costs for a poverty-stricken health system which is not based on preventative medicine but would assume the great cost involved in treating chronic diseases.

The present investigation arose from the foregoing considerations and was aimed at studying treatment adherence in hypertensive patients being attended by Assbasalud ESE (in Manizales, Colombia) and its relationship with social support as perceived by such patients.

Materials and Methods

This was a cross-sectional study in which a population of 200 hypertensive patients (according to JNC 7) were analysed; they were being seen at Assbasalud's healthcare centres in Manizales, Caldas department, Colombia, during the second half of 2011 (ESE stands for empresa social del estado, a state-run entity providing low complexity healthcare services).

The variables considered in the present study were gender, age (in years), social strata (1,2,3,4), educational level (none, primary, secondary, university, postgraduate), years of having been diagnosed, social security affiliation (contributory, subsidised system), frequency of attending the programme (constant, regular, occasionally, non-attendance), knowledge of the disease and its complications (yes, no), indication of low-salt diet (yes, no), low-fat diet (yes, no), indication of physical exercise (yes, no), taking antihypertensive drugs (yes, no), blood pressure level according to JNC 7 (6), antihypertensive treatment adherence according to two questionnaires: the MoriskyGreen (MG) (24, 25) and Martín-Bayarre-Grau (MBG) questionnaires (26) for evaluating therapeutic adherence regarding AHT. The Medical Outcomes Study (MOS) questionnaire was used to evaluate social support (27).

The MG questionnaire has been validated for different chronic diseases; it was originally created by Morisky, Green and Levine in 1986 for assessing compliance with medication schemes in patients suffering from arterial hypertension (AHT); the Spanish version was validated later on by Val Jiménez et al., (24). Since the questionnaire's introduction, it has been used in assessing therapeutic compliance in different diseases, such as AHT, anti-retroviral drugs for human acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS) and osteoporosis, in populations of men and women having an average age of 70 +/- 10 years. It is short and very easy to apply, has high specificity, high positive predictive value and limited sociocultural requirements for understanding it. It is costeffective but has some disadvantages such as underestimating a good complier and overestimating non-compliance, low sensitivity and negative predictive value. It has high reliability (61%) (25), and has been validated on a Spanish-speaking population. It evaluates sick people's attitudes to treatment.

Regarding the MBG questionnaire, Martín-Alonso et al., (26) validated this questionnaire on a Cuban population (n=114); the sample used consisted of patients suffering essential arterial hypertension who were aged older than 20 years and receiving medical treatment. They were attending the healthcare area at the Policlínico Van-Troi in Centro Habana, Cuba. Internal consistency (0.889) was measured with Cronbach's Alpha (26). Content validation results led to considering that the formulation of the items was reasonable, they were clearly defined and their presence in the questionnaire was justified. Three factors emerged from the results: active compliance, autonomy regarding treatment and adhesion complexity, explaining 68.72% (26) of accumulated variance. Its use in the research field was thus seen to be reliable.

Rodríguez et al., (27) examined the MOS questionnaire's psychometric characteristics regarding perceived social support in a sample of 375 subjects. The MOS parameters had highly acceptable values; internal consistency according to Cronbach's Alpha was 0.919 (27). The three-factor maximum likelihood solution with varimax rotation explained 59.86% of variance. It thus seemed to be a valid instrument for evaluating social support.

The investigation began by using a pilot test with 5% of the study population to ascertain the clarity, pertinence and effectiveness of the instrument being used. Nursing assistants were then trained in using the instrument for collecting information and approaching patients. After an informed consent form had been signed, the instrument was then used with the chosen population in Assbasalud's health centres (in Manizales, Colombia) during the second half of 2011.

Statistical analysis involved nominal variables being described by frequency tables and numerical variables by the average and standard deviation. The c2 test was used for testing the relationship between nominal variables and the t-test or analysis of variance were used for determining relationships between nominal and numerical variables, depending on the case. The data was tabulated in Excel 2007 (Microsoft Corp.) and analysed by using IBM SPSS 20 (IBM Corp) and EpiInfo 3.5.1 software (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC)).

Assbasalud's management ratified the project and it was approved by its Ethics and Research committee. The current laws in force in Colombia for health science research projects were respected when carrying out the study.

Results

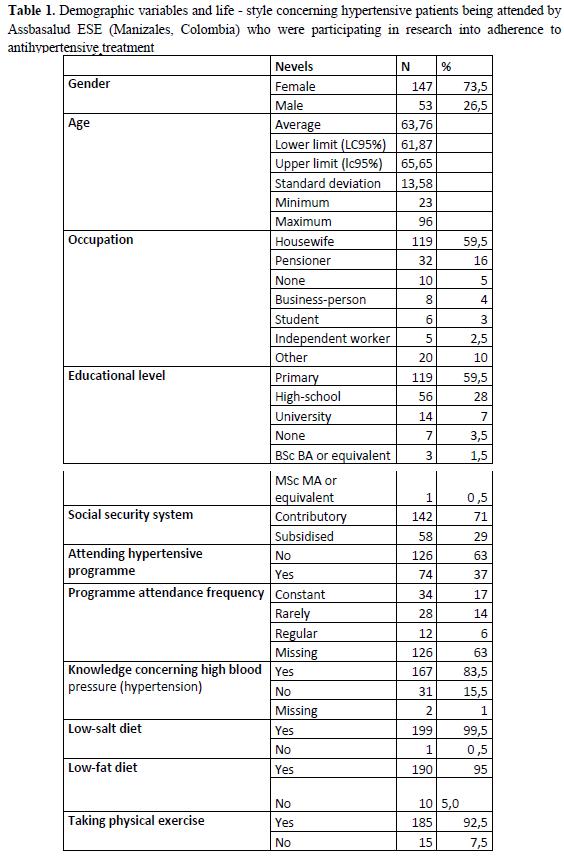

200 hypertensive patients participated in the research. Table I shows that 73.5% of them were female and that participants' average age was 63.7 years. The most frequently occurring occupation was housewife (59.5%), 59.5% of the population had received primary education, most belonged to the contributory social security system (71%) and 37% of the patients were attending Assbasalud's hypertension programme (46% of them constantly). 83.5% stated that they knew about hypertension and its complications, 99.5% of them referred to a low-salt diet having been recommended for them, 95% to a low-fat diet having been recommended, 92.5% to physical exercise and 98.5% to antihypertensive drugs.

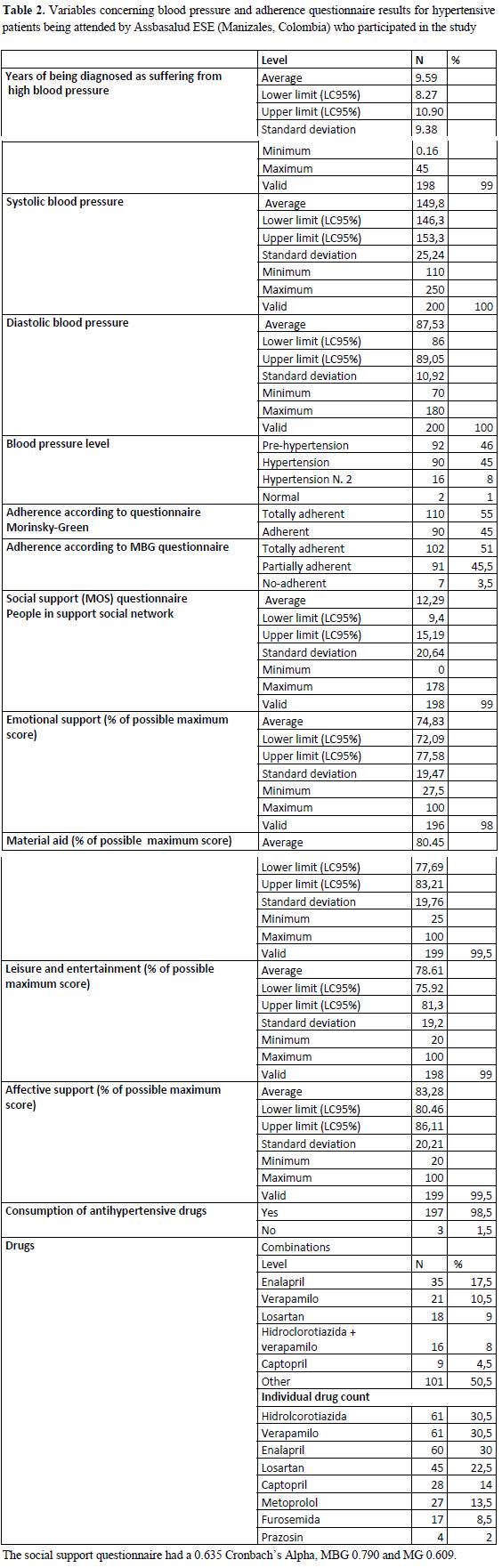

Table 2 shows the variables referring to AHT and the questionnaires used in this study. It can be seen that average AHT diagnosis time was 9.58 years; average systolic blood pressure was 149.79 mmHg and diastolic was 87.53 mmHg. There was 45% total adherence (38-52.5 95%CI) according to the MG questionnaire and 51% total adherence (43.9-58.1 95%CI) according to the MBG questionnaire. The social support questionnaire revealed an average of 12.29 people in patients' social support networks, 74.83% were receiving emotional support, 80.45% were receiving material aid, 78.61% were engaged in leisure and entertainment-related activities and 83.28% were receiving affective support. The drugs most frequently used in individual treatment were enalapril (17.9%; 12.8-23.9 95%CI), verapamil (10.7%; 6.8-15.9 95%CI), losartan (9.2%; 5.5-14.1 95%CI) and a combination of hydrochlorothiazide and verapamil (7.1%; 4-11.7 95%CI). Referring to drug count, the most consumed ones were hydrochlorothiazide (30.5%; 24.2%-37.4 95%CI), verapamil (30.5%; 24.2%-37.4 95%CI) and enalapril (30%, 23.7%-36.9 95%CI).

Relationship between variables

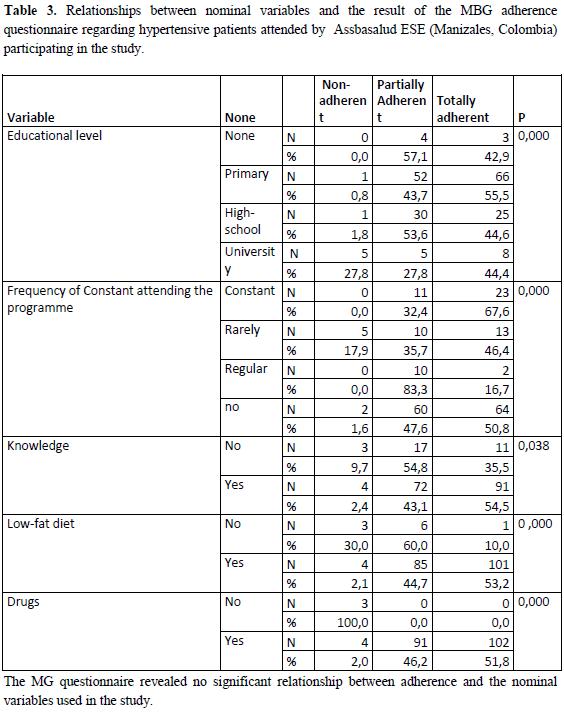

c2 was used for determining the relationship between all nominal variables and both adherence measurements; Table 3 shows the significant relationships.

The MG questionnaire revealed no significant relationship between adherence and the nominal variables used in the study.

The relationship between numerical variables and adherence according to MG was tested using t-tests, finding a significant dependence on age (p=0.048) and diastolic blood pressure (p=0.044). Adherent hypertensive patients' average age was 65.85 years, and non-adherents 62.05 (0.0337.5867 95%CI). Adherents had 85.81 mm Hg diastolic blood pressure and non-adherents 88.93 (

6.153 - -0.079 95%CI).

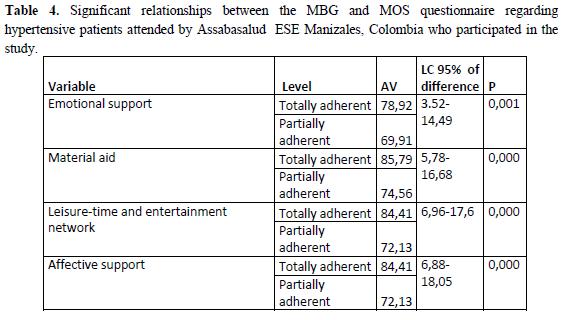

The MBG questionnaire presented just 7 cases of non-adherence; these were thus assumed as missing data when analysing the relationship of dependence to numerical variables (t-tests were thus used). Significant relationships were found with the social support questionnaire (as can be seen in Table 4).

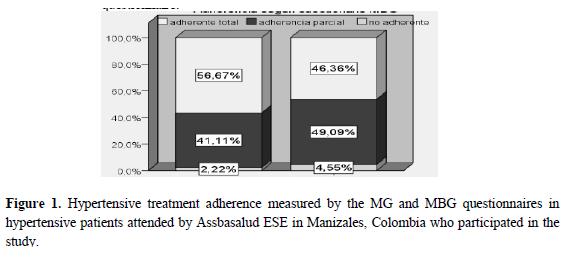

The c2 test related adherence measured by the MG and MBG questionnaires, no significance being found (p=0.288) (Figure 1). It is worth highlighting that amongst non-adherent patients according to the MG questionnaire, 46.36% were found to be totally adherent according to the MBG questionnaire.

Discussion

Results regarding lack of pharmacological adherence agreed with data from Tejero's 1992 study indicating that 29% to 56% (28) of hypertensive people did not take their medication as indicated by a doctor.

The present study found that adherence was 45% according to the MG questionnaire, average systolic blood pressure being 149.79 mmHg and diastolic 87.3 mmHg; adherence was 51% in the aforementioned study by Tejero (28), validating the MBG questionnaire.

It was found that patients stating that they knew nothing about the disease had 9.7% non-adherence according to the MBG questionnaire, 54.8% partial adherence and 35.5% total adherence compared to 2.4% non-adherence, 43.1% partial adherence and 54.5% total adherence for those knowing about it. Such result was analogous to that obtained by Flórez (21) in a 2009 study about treatment adherence in patients from Cartagena (Colombia) having cardiovascular risk factors, greater adherence to antihypertensive treatment being found in people who stated that they knew about the disease.

It was found that 59.5% of patients had primary education, this being lower than that found by Vinacciaet al., (7) in Medellín (Colombia) in 2006 (84.9%) in a study about social support and antihypertensive treatment adherence in patients diagnosed as suffering from AHT.

The MBG questionnaire revealed 100% non-adherence in patients who did not take antihypertensive drugs compared to those who did so (2% non-adherence). Half of the people who took medicaments were totally adherent; this ratio agreed with another study by Holguín (14) in 2006 in Cali (Colombia) which found significantly greater adherence in patients taking such drugs and more so in those undergoing monotherapy.

Patients on a low-fat diet had greater treatment adherence, according to the MBG questionnaire; this agreed with Matos (15) in a 2008 study involving hypertensive patients in Cuba.

Patients' self-declarations were used in the study for assessing pharmacological adherence and social support. Bernal et al., (15) stated that the family formed an individual's primary social support network, being the main resource in promoting health and preventing disease and its harmful effects. Bernal's study found 9.5% of social support networks to be insufficient in nonadherent patients; this dropped to 0.8% in totally adherent patients. Lower scores were found in this study on all social support questionnaire subscales for partially adherent patients.

The present study revealed low antihypertensive treatment adherence according to both the MG (45%) and MBG questionnaires (51%); such adherence was modulated in this population due to factors such as attending Assbasalud's hypertensive programme, knowledge about the disease, educational level, social support network, etc. Action aimed at improving the factors associated with adherence is thus urgently needed, given the low levels of antihypertensive treatment adherence revealed in this study for such population.

The present study has also clearly shown a lack of agreement between the MG and MBG questionnaires (p=0.288; figure 1). This would seem to be logical considering that both questionnaires were measuring different aspects; the MG questionnaire was limited to enquiring about taking (prescribed) drugs, whilst the MBG questionnaire also asked about other aspects such as diet, exercise, attending educational programmes for hypertensive people, whether they discussed their treatment with a doctor, etc. Patients dutifully taking their drugs are adherent according to the MG questionnaire, but when such patients do not follow indications about diet, exercise etc., they could be non-adherent according to the MBG questionnaire due to its multiple dependences. Social support was shown to have a significant dependence on adherence, according to MBG, as this questionnaire measured aspects which could have been influenced by the family setting. According to the definition given in Kastarinen's controlled trial of lifestyle intervention against hypertension in Eastern Finland(22) and the data obtained here it may be concluded that the MBG questionnaire measured adherence better.

This study's main limitation concerned the number of patients, since the sample could not be extended to greater populations due to the cost involved. Another factor which possibly interfered with the results was the technique used for taking blood pressure; it would seem to be easy to measure such vital sign as protocols have been established for suitably taking it and if these are not followed then the results could become subjective. The truth of the patients' replies could have been influenced by the direct relationship between the person administering the questionnaire and the patients, since the atmosphere could have been tense and hostile for the person being consulted.

References

1. Avendaño H. Nefrología clínica. Madrid: Panamericana; 2009.

2. Acosta M, Debes G, De la Noval R, Dueñas A. Conocimientos, creencias y prácticas en pacientes hipertensos relacionados con su adherencia terapéutica. Rev CubanaEnfermer. 2005; 21:(3).

3. Uzun Þ, Kara B, Yokuþoðlu M, Arslan F, Yilmaz M, Karaeren H.The assessment of adherence of hypertensive individuals to treatment and lifestyle change recommendations.AnadoluKardiyolDerg. 2009; 9:102-9.

4. Kearney PM, Whelton M, Reynolds K, Munter P, Whelton PK, He J. Global burden of hypertension: analysis of worldwide data. Lancet. 2005; 365:217-23.

5. Báez L, Blanco de E. MI, Bohórquez R, Botero R, Cuenca G, D'Achiardi R, et ál. Guías colombianas para el diagnóstico y tratamiento de la hipertensión arterial. Rev Col Cardiol. 2007; 13:S187-317.

6. Barreto F, Ruiz M, Borrero J. Hipertensión arterial. Nefrología. 5ª ed. Medellín: editorial CIB; 2012.

7. Vinaccia S, Quiceno JM, Fernández H, Gaviria AM, Chavarria F. Apoyo social y adherencia al tratamiento antihipertensivo en pacientes con diagnóstico de hipertensión arterial. Informes psicológicos. 2006; 8:89-106.

8. Fauci AS, Braunwald E, Kasper DL, Hauser SL, Longo DL, Jameson JL, et ál. Harrison Principios de medicina interna. 17° ed. Mexico DF: MacGraw-Hill; 2009.

9. Lamina S, Okoye CG. Uricaemia as a cardiovascular events risk factor in hypertension: the role of interval training programme in its down regulation. J Assoc Physicians India.2011; 59:23-8.

10. Drost JT, Maas AH, van Eyck J, Van der Schouw YT. Preeclampsia as a female-specific risk factor for chronic hypertension.Maturitas. 2010, 67:321-6.

11. Murgueitio R, Prada G, Archiva P, Pinzón A, Pinilla A, Londoño N, et ál.Métodos diagnósticos en medicina clínica. Enfoque práctico. Bogotá: Editorial CELSUS; 2006.

12. Pinilla A, Barrera M, Agudelo J, Agudelo C. Guía de atención de la hipertensión arterial. Bogotá: Ministerio de Protección Social; 2007.

13. D'Anello S, Barreat Y, Escalante G, D'Orazio A, Benítez A. La relación médico-paciente y su influencia en la adherencia al tratamiento médico. MedULA. 2009; 18:33-39.

14. Holguín L, Correa D, Arrivillaga M, Cáceres D, Varela M. Adherencia al tratamiento de hipertensión arterial: efectividad de un programa de intervención biopsicosocial. UnivPsychol. 2006; 5:535-47.

15. Matos Y, Libertad M, Bayarre H. Adherencia terapéutica y factores psicosociales en pacientes hipertensos. Rev Cubana Med Gen Integr.2007; 23(1).

16. Horne R, Clatworthy J, Polmear A, Weinman J. A Sub-study of the ASCOT Trial Do hypertensive patients' beliefs about their illness and treatment influence medication adherence and quality of life? J Human Hypertens.2001; 15:565-8.

17. Karaeren H, Yokusoglu M, Uzun S, Baysan 0, Koz C, Kara B, et ál. The effect of the content of the knowledge on adherence to medication in hypertensive patients.AnadoluKardiyolDerg. 2009; 9:183-8.

18. Trivedi R, Ayotte B, Edelman D, Bosworth H.The association of emotional well-being and marital status with treatment adherence among patients with hypertension.J BehavMed. 2008; 31:489-97.

19. García A, Alonso L, López P, Yera I, Ruiz A, Blanco N. Reacciones adversas a medicamentos como causa de abandono del tratamiento farmacológico en hipertensos. Rev Cubana Med Gen Integr. 2009; 25(1).

20. Velandia A, Rivera L. Agencia de autocuidado y adherencia al tratamiento en personas con factores de riesgo cardiovascular. Salud Pública (Bogotá). 2009; 11:538-48.

21. Florez I. Adherencia a tratamientos en pacientes con factores de riesgo cardiovascular. Av Enferm.2009; 27:25-32.

22. Kastarinen M, Puska P, Korhonen M, Mustonen J, Salomaa V, Sundvall J. et ál. Non- pharmacological treatment of hypertension in primary health care: a 2 year open randomized controlled trial of lifestyle intervention against hypertension in Eastern Finland. J Hypertens. 2002; 20:2505-12.

23. Vidalon A. Hipertensión arterial: una introducción general. Acta Med Per. 2006; 23:67-68.

24. Val Jimenez A, Amorós Ballestero G, Martínez P, Fernández ML, León M. Estudio descriptivo del cumplimiento del tratamiento farmacológico antihipertensivo y validación del test de Morinsky y Green. Aten Primaria. 1992; 10:767-70.

25. Garcia AM, Leiva F, Crespo F, Ruiz AJ, Torres D, Sánchez de la Cuesta F. ¿Cómo diagnosticar el cumplimiento terapéutico en atención primaria? Medicina de Familia. 2000; 1.

26. Martin-Alfonso L, Bayarre-Vea HD, Grau-Abalo JA. Validación del cuestionario MBG (Martin-Bayarre-Grau) para evaluar la adherencia terapéutica en hipertensión arterial. Revista Cubana de Salud Pública. 2008; 34:7.

27. Rodríguez E, Carmelo H, Solange E. Validación argentina cuestionario MOS apoyo social percibido. Psicodebate.Psicología, culturasociedad.2007; 7:155-168.

28. Tejero N, Franco R, Morales C, Sanchez J, Campo S. Techniques for Measuring Medication Adherence in Hypertensive Patients in Outpatient Settings Advantages and Limitations. MedClin (Barc). 1992; 99:769-73.

1. Avendaño H. Nefrología clínica. Madrid: Panamericana; 2009. [ Links ]

2. Acosta M, Debes G, De la Noval R, Dueñas A. Conocimientos, creencias y prácticas en pacientes hipertensos relacionados con su adherencia terapéutica. Rev Cubana Enfermer. 2005; 21:(3). [ Links ]

3. Uzun Þ, Kara B, Yokuþoðlu M, Arslan F, Yilmaz M, Karaeren H. The assessment of adherence of hypertensive individuals to treatment and lifestyle change recommendations. Anadolu Kardiyol Derg. 2009; 9:102-9. [ Links ]

4. Kearney PM, Whelton M, Reynolds K, Munter P, Whelton PK, He J. Global burden of hypertension: analysis of worldwide data. Lancet. 2005; 365:217-23. [ Links ]

5. Báez L, Blanco de E. MI, Bohórquez R, Botero R, Cuenca G, D'Achiardi R, et ál. Guías colombianas para el diagnóstico y tratamiento de la hipertensión arterial. Rev Col Cardiol. 2007; 13:S187-317. [ Links ]

6. Barreto F, Ruiz M, Borrero J. Hipertensión arterial. Nefrología. 5ª ed. Medellín: editorial CIB; 2012. [ Links ]

7. Vinaccia S, Quiceno JM, Fernández H, Gaviria AM, Chavarria F. Apoyo social y adherencia al tratamiento antihipertensivo en pacientes con diagnóstico de hipertensión arterial. Informes psicológicos. 2006; 8:89-106. [ Links ]

8. Fauci AS, Braunwald E, Kasper DL, Hauser SL, Longo DL, Jameson JL, et ál. Harrison Principios de medicina interna. 17° ed. Mexico DF: MacGraw-Hill; 2009. [ Links ]

9. Lamina S, Okoye CG. Uricaemia as a cardiovascular events risk factor in hypertension: the role of interval training programme in its down regulation. J Assoc Physicians India.2011; 59:23-8. [ Links ]

10. Drost JT, Maas AH, van Eyck J, Van der Schouw YT. Preeclampsia as a female-specific risk factor for chronic hypertension. Maturitas. 2010, 67:321-6. [ Links ]

11. Murgueitio R, Prada G, Archiva P, Pinzón A, Pinilla A, Londoño N, et ál. Métodos diagnósticos en medicina clínica. Enfoque práctico. Bogotá: Editorial CELSUS; 2006. [ Links ]

12. Pinilla A, Barrera M, Agudelo J, Agudelo C. Guía de atención de la hipertensión arterial. Bogotá: Ministerio de Protección Social; 2007. [ Links ]

13. D'Anello S, Barreat Y, Escalante G, D'Orazio A, Benítez A. La relación médico-paciente y su influencia en la adherencia al tratamiento médico. MedULA. 2009; 18:33-39. [ Links ]

14. Holguín L, Correa D, Arrivillaga M, Cáceres D, Varela M. Adherencia al tratamiento de hipertensión arterial: efectividad de un programa de intervención biopsicosocial. UnivPsychol. 2006; 5:535-47. [ Links ]

15. Matos Y, Libertad M, Bayarre H. Adherencia terapéutica y factores psicosociales en pacientes hipertensos. Rev Cubana Med Gen Integr.2007; 23(1). [ Links ]

16. Horne R, Clatworthy J, Polmear A, Weinman J. A Sub-study of the ASCOT Trial Do hypertensive patients' beliefs about their illness and treatment influence medication adherence and quality of life? J Human Hypertens.2001; 15:565-8. [ Links ]

17. Karaeren H, Yokusoglu M, Uzun S, Baysan 0, Koz C, Kara B, et ál. The effect of the content of the knowledge on adherence to medication in hypertensive patients. Anadolu Kardiyol Derg. 2009; 9:183-8. [ Links ]

18. Trivedi R, Ayotte B, Edelman D, Bosworth H. The association of emotional well-being and marital status with treatment adherence among patients with hypertension. J Behav Med. 2008; 31:489-97. [ Links ]

19. García A, Alonso L, López P, Yera I, Ruiz A, Blanco N. Reacciones adversas a medicamentos como causa de abandono del tratamiento farmacológico en hipertensos. Rev Cubana Med Gen Integr. 2009; 25(1). [ Links ]

20. Velandia A, Rivera L. Agencia de autocuidado y adherencia al tratamiento en personas con factores de riesgo cardiovascular. Salud Pública (Bogotá). 2009; 11:538-48. [ Links ]

21. Florez I. Adherencia a tratamientos en pacientes con factores de riesgo cardiovascular. Av Enferm.2009; 27:25-32. [ Links ]

22. Kastarinen M, Puska P, Korhonen M, Mustonen J, Salomaa V, Sundvall J. et ál. Non- pharmacological treatment of hypertension in primary health care: a 2 year open randomized controlled trial of lifestyle intervention against hypertension in Eastern Finland. J Hypertens. 2002; 20:2505-12. [ Links ]

23. Vidalon A. Hipertensión arterial: una introducción general. Acta Med Per. 2006; 23:67-68. [ Links ]

24. Val Jimenez A, Amorós Ballestero G, Martínez P, Fernández ML, León M. Estudio descriptivo del cumplimiento del tratamiento farmacológico antihipertensivo y validación del test de Morinsky y Green. Aten Primaria. 1992; 10:767-70. [ Links ]

25. Garcia AM, Leiva F, Crespo F, Ruiz AJ, Torres D, Sánchez de la Cuesta F. ¿Cómo diagnosticar el cumplimiento terapéutico en atención primaria? Medicina de Familia. 2000; 1. [ Links ]

26. Martin-Alfonso L, Bayarre-Vea HD, Grau-Abalo JA. Validación del cuestionario MBG (Martin-Bayarre-Grau) para evaluar la adherencia terapéutica en hipertensión arterial. Revista Cubana de Salud Pública. 2008; 34:7. [ Links ]

27. Rodríguez E, Carmelo H, Solange E. Validación argentina cuestionario MOS apoyo social percibido. Psicodebate. Psicología, cultura sociedad. 2007; 7:155-168. [ Links ]

28. Tejero N, Franco R, Morales C, Sanchez J, Campo S. Techniques for Measuring Medication Adherence in Hypertensive Patients in Outpatient Settings Advantages and Limitations. MedClin (Barc). 1992; 99:769-73. [ Links ]

text in

text in