Introduction

During pregnancy, mother's physiology adapts to provide nutrients to the growing fetus. However, the imbalance in the amount of triglycerides (TG) -either before or during pregnancy- has been related to maternal-perinatal pathologies such as preeclampsia (PE) and gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM). In neonates, reported pathologies include preterm delivery (PD), dystocia, macrosomia, hypoglycemia or intrauterine growth restriction. 1-6

In Colombia, 7 482 cases of severe maternal morbidity (SMM) were reported during the first semester of 2016, which corresponds to 27.9 mothers for every 1 000 live births (LB), and 182 cases of maternal mortality, with 49.2 cases for every 100 000 LB. 7 The main causes of SMM and maternal mortality were hypertensive disorders (62.4% and 15.5%, respectively) and hemorrhagic complications (15.5% and 18%, respectively). 7

Exacerbated hypertriglyceridemia and insulin resistance condition an oxidative environment that leads to endothelial injury, which, in turn, has a predisposing effect on the development of PE as a hypertensive disorder of higher incidence. 8-10 Intrauterine weight gain may be associated with the elevation of TG passage through the placenta and TG production by the fetus, which would lead to a large for gestational age (LGA) fetus and, thus, possible hemorrhagic complications during delivery by overdistension and uterine rupture. 6,11,12

Besides short-term complications associated with hypertriglyceridemia, other long-term complications involve metabolic disorders and cardiovascular diseases (CVD) that may affect the well-being of the child during adulthood and the health of the mother in her middle and late adulthood. 13-16 The objective of this work is to perform a comprehensive literature review on the pathophysiological causes, effects on mother and child, expected TG values in each trimester of pregnancy and possible therapies to manage maternal hypertriglyceridemia in a timely manner.

Increase in circulating triglycerides during pregnancy

Pregnancy is a state of metabolic stress associated with high TG levels 17, which increase during this period; the highest concentrations are observed during the third trimester. 1 This increase is related to the decrease in the synthesis of fatty acids and the activity of the lipoprotein lipase (LPL) that catalyzes the hydrolysis of TG-rich lipoproteins in the adipose tissue. 1 The activity of this enzyme decreases about 85% during a normal pregnancy. 2,17 TG levels decrease in the postpartum period and this decrease is faster in women who lactate. 18

The abovementioned events are related to the insulin resistance that occurs during pregnancy, which may be caused by the increase of non-esterified fatty acids, changes in adipokines secretion and inflammatory factors. 1,2,17 Increased lipolysis has been associated with increased placental lactogen, progesterone, prolactin, cortisol and estrogen. 2,19 Adiponectin and apelin, which favor insulin sensitivity, decrease in the third trimester, while other adipokines and cytokines that reduce insulin sensitivity increase at the end of pregnancy, including resistin, retinol binding protein 4 (RBP4), leptin, visfatin, chemerin, adipocyte fatty acid binding protein (AFABP), tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α) and interleukin-6 (IL-6) 2. In addition, the expression of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma (PPAR-γ) in adipose tissue decreases in the third trimester, contributing to insulin resistance. 2

Placental passage of maternal triglycerides

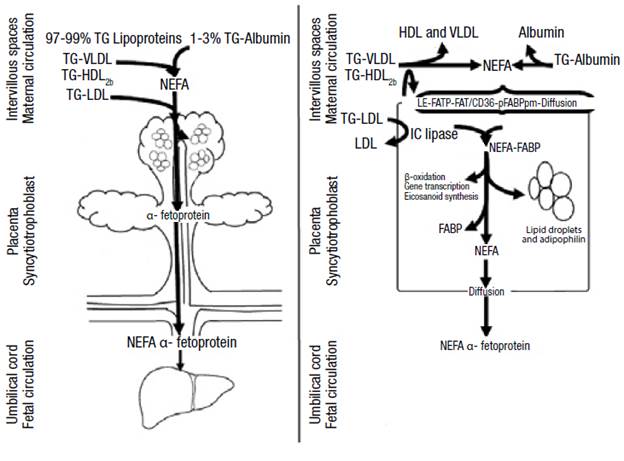

1-3% of maternal fatty acids circulate in non-esterified form and enter the syncytiotrophoblast through diffusion or receptor-mediated endocytosis. 3 Low-density lipoproteins associated with TG (LDL-TG), more abundant in circulation, are hydrolyzed by intracellular lipases and cholesterol ester hydrolases. On the other hand, high density lipoproteins (HDL) and very low density lipoproteins (VLDL) bind to surface receptors and are hydrolysed extracellularly by endothelial lipase. 2,3,16 Transporters such as fatty acid transport protein 1 and 4 (FATP-1 and FATP-4), fatty acids translocase (FAT/ CD36) and plasma membrane fatty acid-binding protein (FABPpm) make fatty acid uptake a more efficient process. 3,16

At the intracellular level, the fatty acids bind to the fatty acid binding protein (FABP), which has intrinsic acetyl-CoA ligase activity. 16 Then, the syncytiotrophoblast releases fatty acids into the fetal circulation to bind to the α-fetoprotein (AFP) that takes them to the fetal liver where they are metabolized (Figure 1). 2,12,16 It should be noted that lipid droplets have been observed in the placenta and that their formation is stimulated by adipophilin. 16

Source: Own elaboration based on Barrett etal.16

Figure 1 Passage of triglycerides through the placenta. TG: triglycerides; VLDL: very low density lipoprotein; LDL: low density lipoprotein; HDL: high density lipoprotein; FATP: fatty acid transport protein; FAT/CD 36: fatty acid translocase; FABPpm: plasma membrane fatty acid-binding protein; IC: intracellular; FABP: fatty acid binding protein; NEFA: non-esterified fatty acids.

White adipose tissue is observed in the fetus since week 14 or 15, while fetal lipogenesis begins at week 12 or 20; PPAR-γ activation plays an important role in the subsequent increase of adipose tissue size. 20 Fetus weight increases fourfold from 1.6 g/kg/day to 3.4 g/ kg/day since the 26th week of pregnancy, but the increase in fetal body fat depends by 20% on placental lipid transfer; the remaining tissue results from fetal lipogenesis. It is worth noting that only one third of circulating maternal glucose is used by placenta through lipolytic routes and the demand is not modified by increasing glucose levels because the utilization is saturated between 90 mg/dL and 143 mg/dL. 2

Hypertriglyceridemia and pathologies

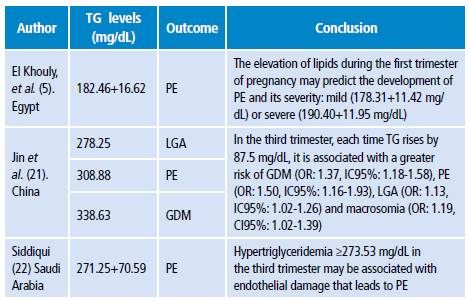

A study carried out in Amsterdam (n=4 008) revealed that TG increase in the first trimester of pregnancy is directly associated with pregnancy-induced hypertension, PD and LGA. 3 Likewise, a research carried out in India (n=180) found that high TG levels (>195 mg/dL) in the second trimester are associated with a higher incidence of PD, GDM, PE and LGA. 4 Another complication is maternal pancreatitis, which must be mentioned due to its severity (Table 1). 14,18

Table 1 Outcomes of gestational hypertriglyceridemia according to different studies.

PE: preeclampsia; TG: triglycerides; GDM: gestational diabetes mellitus; LGA: large for gestational age fetus.

Source: Own elaboration based on the data obtained in the study.

In the mother

Preeclampsia

Between 2% and 8% of pregnancies are complicated by PE, which is the third cause of maternal-fetal death after hemorrhage and sepsis. 14,23-25 In the mother, this condition is associated with endothelial dysfunction, hypertension, kidney disease and diabetes mellitus (DM). It also increases the risk of developing CVD and death due to kidney and liver impairment. 14 Hypertriglyceridemia, before or during pregnancy, alters the vascular development of the placenta and results from inadequate implantation or placental perfusion. 3,5,8 PE and dyslipidemia are correlated because LPL dysfunction, metabolic syndrome and increased plasma lipids occur in both. 4 These disorders stimulate peroxidation of placental lipids and trophoblast components that promote oxidative stress and form deleterious complexes in endothelial cells that cause vascular dysfunction. 4,5

A prospective cohort study conducted in Egypt (n=251) showed that TG levels between weeks 4 and 12 of pregnancy can be predictors of PE development. 5,8 This study found that the increase in total cholesterol (TC), TG and LDL greater than 231 mg/dL, 149.5 mg/ dL and 161 mg/dL, respectively, and the decrease in HDL below 42.5 mg/dL are cutoff points with positive predictive value for the development of PE, while TC and TG increase was related to severity. 5 Another study conducted in Turkey (n=52) found that TC, TG and LDL increase greater than 4%, 5% and 9.8%, respectively, and a decrease in HDL by more than 9% are associated with worse prognosis of gestational hypertensive disease. 26

The study by Manna et al.27 in Bangladesh (n=90) showed that increased TG levels are directly associated with an increase in blood pressure. In the study group, systolic and diastolic pressures were 152.4±19.8 mmHg and 103.1±12.2 mmHg, respectively, while in pregnant controls, they were 112.0±8.9 mmHg and 75.5±6.6 mmHg, respectively. 27 These numbers were associated with TG levels in the study group (242.9±36.8 mg/dL) and in the control group (184.6±12.5 mg/dL). 27TG>181 mg/dL before week 20 increased the risk of PE by 3 to 7 times. 28

A study conducted in Mexico with 47 normotensive women and 27 with PE or gestational hypertension in the seventh month of pregnancy showed that hypertriglyceridemia is related to hypertensive disorders in pregnancy. Researchers found that nitric oxide (NO) synthesis decreased proportionally to the increase of TG levels. 8 NO decrease may be secondary to oxidative stress increase considering the high concentration of TG or glucose that inhibits NO synthesis. 29 In this study, women with hypertensive disorders of pregnancy were treated with hydralazine, which induces NO synthesis. 8 It has been observed that the increase of fatty acids in the placenta of women with DM1 is related to reduced fetal-placental circulation and that having a family history of DM2 is closely related to an increased risk of developing hypertensive disorders during pregnancy. 2

Gestational diabetes mellitus

The prevalence of GDM has gone from 4% to 20% in 27 years and its current incidence is 1-14%. 30,31 This pathology not only increases the risk of PE and macrosomia during pregnancy, but also predisposes the mother to the development of DM2 and CVD. 12 Mothers with GDM have hypertriglyceridemia, hypercholesterolemia, insulin resistance, low levels of adiponectin and increased intracellular concentrations of AFABP 2; therefore, they are characterized by having insulin resistance. 4,12,29

Alterations have been found in the fetus and placenta related to imbalances in the expression and function of PPARs isotypes that increase lipid flow in women with hyperlipidemia and GDM. 2,9,10

Concentrations of PPAR-γ and PPAR-α are low in term-placental tissue of women who developed GDM, whereas no changes are detected in PPAR-δ concentrations. 9,10 No changes were found in PPAR-γ concentrations in women with DM1; however, decreased levels of 15-deoxy δ-12, 14-prostaglandin J2 (15dPGJ2) were observed. 9 Also, alterations in the expression of PPAR-α during the first trimester of pregnancy are associated with spontaneous abortions. 10 15dPGJ2 increases lipid concentrations and significantly reduces NO expression in the placenta of healthy women, while it regulates the increase in the concentrations of phospholipids and cholesterol esters in the placenta of diabetic women. 9 In addition, its receptor (PPAR-γ) is decreased in these patients, which could increase NO and lipid peroxidation, markers of pro-inflammatory and pro-oxidant states. 9

A case-control study (n=254) conducted in the USA by Han et al.32 found that the measurement of the pregestational lipid profile is a predictor of GDM. This study revealed that women who developed GDM, in comparison with the controls, presented smaller LDL diameters, low concentrations of HDL and high levels of small VLDL regardless of other risk factors (body mass index -BMI-, weight gain during pregnancy, age or ethnicity) in measurements taken even up to 7 years before pregnancy. 32,33 On the other hand, the risk of developing GDM is 3.5 times higher if TG >137 mg/dL in the first trimester. In addition, every time TG increase by 20 mg/ dL, the risk of developing DMG increases by 10%. 34

Pancreatitis

Acute pancreatitis caused by gestational hypertriglyceridemia is a rare complication of pregnancy but, when it occurs, it represents high maternal and fetal morbidity and mortality 1,15,16,18 and may be complicated by pancreatic necrosis, shock, hypokalemia, PE or eclampsia. 15 The risk of developing pancreatitis increases progressively with TG >500 mg/dL. 15 Thus, during the first trimester, these increased levels are associated with a 19% risk of pancreatitis, in the second with 26%, in the third with 53% and in the postpartum with 2% 1,15, depending on the activity of pancreatic lipase and liver involvement. 15,18

In the fetus

Macrosomia

Lipids availability and accumulation in the fetus of a mother with dyslipidemia increases the risk of developing macrosomia and PD. 6 A LB presents macrosomia if its weight is >4kg and LGA if its size is above the 90th percentile. 12,14 Giving birth to a LGA fetus increases the likelihood of prolonged labor, cesarean or postpartum hemorrhage. In addition, giving birth to fetuses with macrosomia makes women 4.2 times more susceptible to developing DM2 throughout their lives. 35 Hypoglycemia, hyperbilirubinemia, respiratory distress, cardiac hypertrophy, shoulder dystocia, clavicle fracture, and brachial plexus injuries may occur in the newborn. 36,37

A Cuban case-control study (n=236) showed that the increase in TG levels during the third trimester was a predictor of the development of fetal macrosomia (OR:4.80, CI95%: 2.34-9.84). 6 Another study conducted in Chile in patients with well-controlled GDM and hypertriglyceridemia found that macrosomia was more frequent in women with pre-pregnancy overweight or obesity. 12,38,39 A BMI >26.1 kg/m2 was a predictor of macrosomia regardless of hypertriglyceridemia during the first trimester of pregnancy 40, perhaps due to the fact that free fatty acids act as growth factors and, that in high concentrations, they compete for the binding site of sex hormones to albumin, which increases the levels of free hormones that could act on the placenta and the fetus, thus modifying its growth and development. 3 It is noteworthy that the levels of circulating leptin in pregnant women with GDM, PE, intrauterine growth restriction or macrosomia have not been shown to have a predictive value on the weight of the newborn. 41

Contrary to the increase in TG, recent studies suggest that low levels of omega 3 fatty acids during prenatal life influence adiposity in children, not only in intrauterine life, but also in the postnatal period. 42,43 Low concentrations of omega 3 fatty acids are associated with lower weights. In turn, a study conducted in India identified that the placenta of term infants with low weight had lower levels of docosahexaenoic acid (DHA) compared to term neonates weighing > 2 500g. 43

Preterm delivery

PD is the leading cause of neonatal morbidity and mortality and occurs in 12% of births. 14,44 Its risk increases to 60% if there is a history of DM1, DM2 or pregestational hyperlipidemia and to 33.3%, if there is hypertriglyceridemia in the third trimester. 44-46

Variants in LPL

Polymorphisms in the LPL gene (S447X, N291S and D9N) are associated with exaggerated increase in TG levels during pregnancy. 17,18 In addition, two APOAV polymorphisms, -1131T>C and S19W, are related to increased VLDL secretion and increased circulating TG levels of 11% and 16.2%, respectively. 18 An interesting correlation has been found between APOAV (-1131T>C), maternal size and crown-rump length of the fetus. 18

Measurement of triglycerides during pregnancy

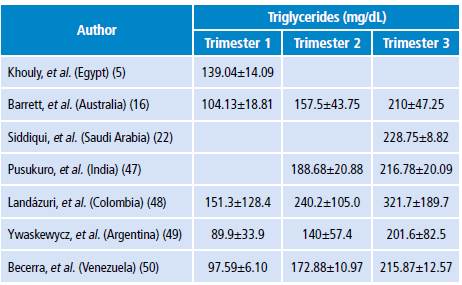

In practice, measuring the concentrations of circulating TG once every trimester is advisable, since increased TG levels are normal during pregnancy (Table 2). Clinically, xanthomas on the external surface of arms, legs and buttocks, retinal lipemia, hepatosplenomegaly and lipemic serum are very suggestive of severe hypertriglyceridemia. 15

Table 2 Normal triglycerides levels during pregnancy.

Source: Own elaboration based on the data obtained in the study.

A study conducted by Landázuri et al.48 in Colombia (n=422) found that TG levels were 86% higher during the second trimester of pregnancy and 137.8% in the third compared to the first. The authors followed 56 of these pregnant women throughout their pregnancy and observed a TG increase of 58.8% from the first to the second trimester and of 112.6% from the first to the third trimester (p<0.001). 48 In this study, low HDL levels were observed compared to the European or North American population during pregnancy. 46,47 Low HDL serum levels could be an additional risk factor for cardiovascular or gestational diseases in Colombian mothers and their children. 51

Studies to evaluate the lipid profile of normal pregnant women have allowed proposing physiological levels for different populations. Thus, the study conducted by Ywaskewycz et al.49 (n=291) in pregnant women without complications showed a TG increase of 56% from the first to second trimester and of 124% from the first to the third trimester; in the third trimester, the increase was twofold as compared to non-pregnant controls, and no differences were observed between TG in the first trimester and TG in non-pregnant women. 49 In addition, the TG/cHDL ratio increases during pregnancy, thus indicating the presence of LDL proteins of smaller size, rich in TG, denser and with higher atherogenic risk. 49

On the other hand, the study by Becerra et al. (50) (n=91) with healthy pregnant women found that TG levels increased significantly (p<0.001) from the first to the second and third trimesters, and that the TG/cHDL ratio was correlated to pre-pregnancy BMI, fetal abdominal circumference, estimated fetal weight and uterine height. (p<0.01)

Treatment of hypertriglyceridemia during pregnancy

The treatment of hypertriglyceridemia depends on how high lipids are. If moderate (200-999 mg/dL), a strict low-fat diet with nutritional support with medium-chain TG and ω-3 fatty acids is initiated while increasing physical activity. Dietary supplementation with DHA and eicosapentaenoic acid reduces the production of proinflammatory cytokines (TNF-α, IL-1, IL-6 and IL-8) and inhibits the synthesis of VLDL without altering that of HDL. 15,16,52

If hypertriglyceridemia is severe (>1000 mg/dL), using medications such as fibrates (PPAR-α agonists), statins, niacin, heparin or insulin is considered. Other possible alternatives are carbaprostacycline and iloprost, drugs that activate PPAR-δ and glitazones, which are synthetic ligands for PPAR-γ. 15,53 However, to the extent possible, using medications should be avoided during the first trimester of pregnancy, since many are contraindicated due to the potential harm to the fetus. It should be noted that using statins and fibrates has been described in case reports.

In case dyslipidemia is refractory to drugs or nutrition, plasmapheresis is initiated. 54 This procedure is also indicated when serum lipase levels are >3 times the normal limit of this enzyme or when hypocalcemia, lactic acidosis and worsening of inflammation or organic dysfunction occur; this can also be combined with heparin infusion. 55,56 When TG levels are below 500 mg/dL, this procedure should be stopped 55,56; however, if contraindicated or not available, infusion of regular insulin with 5% dextrose is used and glucose levels must be maintained between 150 mg/dL and 200 mg/dL during therapy. 15,53 When TG levels are normalized, the next step is to perform a rigorous control of the lipid profile, long-term dietary restriction and administration of fenofibrate. 15,16 In severe hypertriglyceridemia, PD is induced considering the high risks of maternal and fetal mortality (20% and 50%, respectively) and secondary pancreatitis. 1,15,16

A study conducted by Kern-Pessoa et al.57 in Sao Paulo (n=73) found that TC and TG levels increased during pregnancy and decreased from the third to the sixth postpartum week in women with GDM. 57 In this study, LDL and TG levels increased during pregnancy in patients who received insulin, and decreased in those treated with a strict low-fat diet, rich in ω-3 fatty acids as therapy. 57

Conclusions

During pregnancy, TG concentrations increase as a physiological adaptation mechanism, but if they reach very high levels, they become a risk factor for the mother and the child in the short and long term. The metabolic stress observed during this stage is associated with a decrease in the synthesis of fatty acids and the activity of lipoprotein lipase that elevates non-esterified fatty acids and increases insulin resistance. Greater lipolysis is associated with the increase of hormones (progesterone, prolactin and estrogens), cytokines (TNF-α and IL-6) and adipokines (leptin, visfatin and resistin), and with the decrease in adiponectin and apelin, which together reduce insulin sensitivity. For this reason, the availability of TG bound to lipoproteins such as VLDL increases for transplacental passage of fatty acids to the fetus through diffusion, hydrolysis and membrane transporters. These fatty acids reach the fetal liver attached to the α-fetoprotein.

Hypertriglyceridemia increases the risk of pregnancy complications, especially in pregnant women with a history of obesity or overweight, uncontrolled diabetes and familial dyslipidemia. In pregnant women, GDM and acute pancreatitis are the main complications of hypertriglyceridemia; on the other hand, PD, macrosomia and LGA fetuses are the main complications for the product of pregnancy.

For treatment, some case reports have described the use of statins and fibrates in pregnant women with severe hypertriglyceridemia; however, the use of these medications could generate more risks than benefits for the fetus, so its formulation is not recommended during pregnancy.

The limited number of studies and the great variability of the data indicate the need to conduct more research in Colombia to establish the normal ranges of TG during the three trimesters of pregnancy. This could facilitate diagnosis and monitoring of hypertriglyceridemia throughout pregnancy. On the other hand, it is important that health professionals understand the importance of measuring TG levels before pregnancy to determine risks and effective interventions and reduce maternal and child morbidity and mortality.