Introduction

Eating disorders (ED) are complex disorders that involve two types of behavioral disorders: some directly related to diet and weight, and others derived from the relationship with oneself and with others. These disorders have become an emerging pathology in developed and developing countries, being the third most common chronic disease among adolescents after obesity and asthma. 1 EDs caused by food restriction are classified as anorexia nervosa (AN), bulimia nervosa (BN) and disorders not otherwise specified in the DSM-5. 2

AN is a psychiatric disease characterized by a significantly low body weight and fear of gaining weight. Its most important feature is an alteration in the way how an individual perceives self-image or weight; in fact, this distortion of body image is a diagnostic criterion. 3,4 For its part, BN is manifested by episodes of excessive food intake, followed by compensatory behavior in order to minimize or eliminate the effects of the excess, including purges, fasting or exercise. Unspecified behavioral disorders include binge eating disorder and other eating disorders that do not meet the clinical criteria of AN or BN. 4,5

The causal risk factors of eating disorders are multifactorial, as they result from the complex interaction of psychological, physical and sociocultural factors that interfere with the behavior of the individual, making their etiology difficult to understand. 5 This makes them complex pathologies that require a multidisciplinary approach, involving professionals like psychologists, psychiatrists, doctors, nutritionists, among others. Likewise, research on ED has increased, perhaps due to the growing incidence reported in the last decade; the serious physical, psychological and social consequences that have caused these disorders 6, and because they involve mainly children and adolescents, who are going through a growing stage, developing their personality and self-esteem, and strengthening habits that will remain for a long time. 85% of EDs begin during adolescence 7, with serious repercussions for life.

According to estimates, eating disorders affect between 1% and 4% of the general population, especially adolescent and young adult women, with a distribution of 0.5% to 3% for AN and 1% to 4% for BN. 3.2% of women between the ages of 18 and 30 have some type of eating disorder regardless of their socioeconomic status. In addition, it has been found that EDs in men have a prevalence of 5% to 10% of that estimated for women 7; AN and BN affect about 3% of women throughout their lives and it could be said that 90-95% of cases occur in women. Regarding AN, most cases occur in young women, but men seek treatment more often (5-10%). 8 In teenagers, prevalence ranges between 0.3% and 2.2%, being higher in females. However, some studies in adolescents aged between 13 and 18 years have not found significant differences over time between both sexes. During middle and late adolescence, women are at greater risk. 5

On the other hand, pilot tests done in schools of Bogotá D.C. have found that the percentage of girls with anorexia matched figures worldwide, that is, between 1% and 4%. 9 A prevalence of 17.7% was estimated in the university population of Medellín, where 0.8% is for AN, 2.3% for BN and 14.6% for non-specific ED. 7

There are several questionnaires designed to screen and identify EDs, one of them is the Eating Attitudes Test (EAT), designed by Garner & Garfinkel 10 to assess abnormal feeding attitudes, especially those related to fear of gaining weight, the urge to lose weight and the presence of restrictive eating patterns. The EAT is an easy instrument to apply and correct, and is sensitive to symptomatic changes over time. At first, it was a 40-item instrument adapted to the Spanish language, and then, through a factor analysis, a 26-item version was developed, which is highly predictive and which, in turn, was adapted to Spanish. 10

The purpose of this research was to identify the risk of suffering from eating disorders in sixth through eighth grade students of a private school in Bogotá D.C., Colombia, by applying the Eating Attitudes Test (EAT-26) for screening purposes. It is worth mentioning that this research addresses the issue of identifying the risk of suffering from eating disorders because it was determined using a validated survey; the disease was not diagnosed.

The research was carried out in sixth to eighth grade students considering the psychological and physical changes experienced by this population during their transition from elementary to high school, since they achieve more freedom at this point regarding food selection and parents may reduce supervision on this aspect. In addition, at this stage of life eating habits begin to consolidate and are closely linked to the environment of the children and their culture; during this period, the importance of self-esteem and self-acceptance regarding body image to feel accepted in their environment is evident. 11

The identification of the risk of developing an ED is important to plan and carry out appropriate interventions that avoid the deterioration of the health condition of the subjects involved, taking into account the stage of development in which they are and the severity of the symptoms that they may present. 12

Materials and methods

This was a quantitative and transversal study; the sample included sixth through eighth graders of a private school of Bogotá D.C. and was constituted by 990 students who, voluntarily, with prior informed consent by the legal guardian and with the child's consent, decided to participate in the study. The age range of the participants was 10 to 15 years.

The updated version of the study, as well as this article, were approved by the Ethics Committee of the Faculty of Medicine of the Universidad Nacional de Colombia through Act 013-238-18 of September 14, 2018 and followed the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki 13, the guidelines for good clinical practice and the ethical aspects specified in Resolution 8430 of 1993 of the Colombian Ministry of Health 14, Title II, Chapter I, where respect for dignity and protection of the rights and welfare of the participants prevailed. According to this resolution, this study was considered as a minimum risk investigation 14, once the instrument was applied during interviews. The parents of children with a certain risk were summoned to inform them of the results and possible options to follow.

The instrument used was the EAT-26 test, an attitudinal questionnaire that indicates the risk of suffering from an eating disorder that consists of 26 questions that inquire about the behaviors of people suffering from a disorder, among them, vomiting after eating, feeling guilty after eating high-calorie foods, exercising to burn calories, and others. The cut-off point for identifying the risk of suffering from an ED was a score ≥20; a higher score meant a greater number of abnormalities in the eating behavior. 15,16

This instrument has been used and validated by several national and international studies to assess the presence of symptoms of eating disorders. In a validity study conducted by Constain et al.17, the EAT-26 showed a 92% reliability; these authors concluded that the instrument was "appropriate for screening possible EDs, contributing to early detection in young women." Likewise, the study by Vera-Morejón 18 determined a test sensitivity of 48.5%, a specificity of 94% and a efficiency of 77%, concluding that the EAT-26 is a valid test for detecting EDs, which can be applied in mixed populations (composed of men and women) and with high specificity.

For this research, the information was analyzed using descriptive statistics in the Microsoft Excel 2010 program.

One of the limitations of this research is the fact that the responses of the test are self-reported, reason why the participants could have omitted or failed to tell the truth in order to conceal information when they were informed about the objective of the test and the possible social and family implications of completing it with honesty.

Results

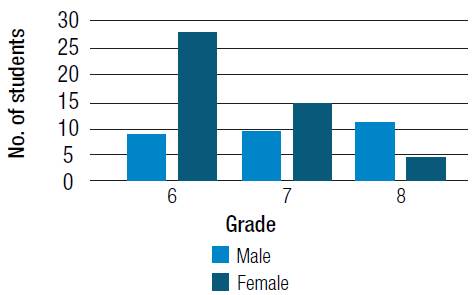

The sample selected for the study was composed of 979 sixth to eighth grade students, 523 boys and 456 girls, of a school in Bogotá D.C.; the age range of the participants was 10 to 15 years. The distribution was made by grade as follows: 311 students of the sixth grade, 335 of the seventh grade and 333 of the eighth grade.

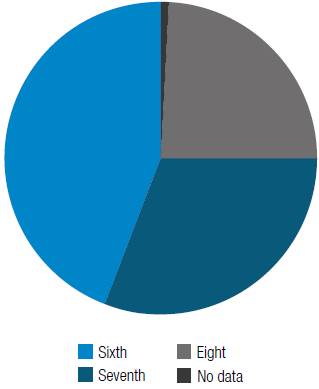

A 9.4% prevalence of risk of suffering eating disorders was found. Regarding the distribution by sex, it was slightly higher in boys (9.8%) in comparison with the prevalence observed in girls (9.2%) . The highest incidence of cases identified as having a risk of developing EDs was found in the sixth (44%) and seventh (31%) grades (Figure 1).

In the lower grades, male students present a higher number of symptoms or risk behaviors for developing EDs, and as the school grade increases, there is a predominance of risk in the female sex (Figure 2).

Discussion

The prevalence of EDs found in this investigation is higher compared to studies conducted in other schools of Colombia; for example, the risk found in Santander was 5.8% for bulimia and 1.7% for anorexia. 19 Another study conducted in Bucaramanga, which sought to determine the internal consistency and criterion validity of the eating behavior survey (Encuesta de Comportamiento Alimentario - ECA) in adolescents, reported the following prevalence figures: 1.6% for AN, 3.1 %for bulimia and2.75% for unspecified EDs. 19

A study, conducted in a Mexican population with an average age of 16.71 years and from various communities of the municipality of Tejupilco, found that 14% of men and 20% of women were prone to develop EDs and related symptoms 4, figures higher than those found in this research, perhaps because the mean age was higher in the aforementioned study.

As reported by Moreno-González & Ortiz-Viveros 20 in another study on the relationship between EDs and self-esteem, a greater tendency to suffer from these disorders was observed in women, with a percentage of 12% in the reported clinical cases, compared to the 4% reported for men. Also, in an study carried out in Bogotá D.C. and in the central savannah of Cundinamarca in students aged between 12 and 20 years who responded the EAT-26 test and the Zung Self-Rating Anxiety Scale, the frequency of EDs found in the screening phase was 15.1%. This research clearly showed that EDs occur at an early age. 21

On the other hand, a study carried out in Lima, Peru, in which 483 female students with an average age of 14 ± 3 years were included, found that 13.9% of the participants were at risk of developing EDs 22, a percentage higher than that reported by the present study, with the difference that the population was exclusively female in the Peruvian study.

Regarding men and women who are at risk of suffering from EDs, the results of this research are similar to those found in a study conducted by Unikel et al.23 in Mexico to identify risk behaviors in students aged between 13 and 18 years. However, the same study showed that risk behaviors increase as age increases, which contrasts with this research, where a greater risk was found in students of lower grades, while a decrease in the number of cases with risk behaviors for EDs was observed as age increased.

In terms of sex comparison, the results of a study conducted in adolescent students from the metropolitan area of Bucaramanga show that the SCOFF questionnaire had an internal consistency of 0.521 in males and 0.584 in females. On the other hand, factor analysis showed a factor that explained 34.7% of the variance in males and a factor responsible for 37.5% of variance in females. 24

EDs can negatively impact a child's health status and cognitive development, so, according to the results reported here, it is necessary to design different strategies to prevent the onset of this condition in school populations, as well as the inclusion of a food and nutrition education program in school curricula in order to improve nutritional and eating habits in this population; in this way, long-term complications will be avoided. In addition, it is essential to inform the parents of the students at risk of suffering from EDs about the nutritional behavior of their children, so that these disorders can also be prevented and treated at home.

Conclusion

This study found that the children at highest risk of suffering from EDs were males, especially at young ages, which corresponds to sixth grade students aged between 11 and 12 years. These results differ from those reported by other studies because of the context and age of the participants. For this reason, future studies should be carried out in other private schools of Bogotá D.C. to have more elements of analysis on the prevalence of this type of EDs in this population.