Introduction

In Colombia, child labor is defined as a situation in which work is carried out by a children or an adolescent whose age is below the minimum age required to perform such activities in accordance with the relevant national regulations or international standards adopted by the country, and therefore, it is likely to prevent children from accessing education and achieving a full development; or as a situation in which children or adolescents are involved in activities that can be classified as hazardous child labor, or as a situation in which the work performed by them is unquestionably within the worse forms of child labor. 1 Likewise, in Colombia the minimum age for admission to employment is 15 years, but those aged 15-17 years need to be authorized by the respective labor inspector or the local competent authority.

Child labor is an important social problem that must be addressed by both government institutions and the Academy. According to the International Labor Organization (ILO), it affects 168 million children worldwide.

In Colombia, in the last quarter of 2017, there were 869 000 working children and adolescents, which represented 7.8% of the economically active population of the country. 2 According to the Colombian National Administrative Department of Statistics (DANE, for its acronym in Spanish), in 2014 most of working children and adolescents were found in the commerce, hotel and restaurants sectors (38.2%), and the agriculture, cattle, hunting, forestry and fishery and aquaculture industries (34.0%). In addition, most of them were classified as unpaid family workers (50.8%), and child labor was associated with a higher school dropout rate, since in child workers dropout rate was 42.4% versus an 11.6% rate in non-working children. 3

Taking this into account, a qualitative study was conducted in order to characterize child labor in the context of agricultural production of rice, coffee, cotton, sugar cane and panela sugar cane in Colombia.

This article presents the results of a literature review of studies and international and national regulations on child labor in the agricultural sector, as well as the characterization of child labor in the production processes of the agricultural crops studied here.

Materials and methods

A qualitative study was conducted in three stages: a) a literature review of studies on child labor in agriculture and how it affects the health and quality of life of children and adolescents was performed by searching relevant documents in several academic databases; b) national and international regulations on child labor were analyzed, and c) a fieldwork was performed to understand how the production processes in these economic subsectors work and to collect social information in an empiric way.

In the last stage two techniques were used: on the one hand, participant observation allowed researchers to get involved in the production processes of each agricultural crop, and, on the other, the use of semi-structured interviews made possible to know the opinions and narratives of different people related to child labor in these agricultural sectors in Colombia.

The fieldwork was conducted in the following municipalities: El Espinal in the case of rice and cotton production; Cali, Buga and Zarzal, in the case of sugar production, and Utica, Villeta and Pensilvania, in the case of panela sugar cane production. These locations were selected because they have been traditionally associated with the production of said agricultural crops and at certain times they have been recognized as places in which most of the national production of these crops has taken place.

Likewise, in order to develop this research the following institutions were contacted: state agencies in charge of addressing child labor in Colombia -mainly the Colombian Family Welfare Institute (ICBF, for its acronym in Spanish), regional offices of the Colombian ]Ministry of Labor, and regional departments of health- and farmers' associations -in particular, the Colombian Coffee Growers Federation (FNC, for its acronym in Spanish) and the regional Coffee Growers Committees, the Colombian Sugar Cane Growers Association (Asocaña, for its acronym in Spanish), the Colombian Panela Sugar Cane Producers Association (Fedepanela, for its acronym in Spanish), and the Colombian Rice Growers Association (Fedearroz, for its acronym in Spanish). In addition, trade unions and social organizations in the abovementioned municipalities were also contacted.

Semi-structured interviews were conducted on 32 people including civil servants, workers, trade unionists and state agencies' experts on child labor; it should be noted that prior to their participation all subjects signed an informed consent form. In order to provide an interview direction, some analytical categories were created (occupational safety, working conditions, monitoring and control measures, and access to education) to synthetize the perceptions of these social actors, as they are essential to address child labor in the context of Colombian agriculture from a social and cultural perspective.

A qualitative and comparative field research was performed and open coding was used to code the interviews 4; also by dividing the responses the different perceptions were compared, which in turn allowed making a generalization of these responses in order to observe certain tendencies in the descriptions and accounts made by the interviewees.

This is a risk-free investigation according to the provisions of Resolution 8430 of 1993 of the Colombian Ministry of Health. 5 Likewise, both confidentiality standard principles and the ethical principles for medical research involving human subjects established by the Declaration of Helsinki 6 were followed. Finally, the development and execution of the study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Faculty of Medicine of Universidad Nacional de Colombia, as stated in Minutes No. 014-254-18 of September 28, 2018.

Results

Next are the findings regarding the literature review on child labor in agriculture and how it affects the health and quality of life of working children and adolescents. In addition, a summary of the regulatory aspects on child labor in Colombia, and the fieldwork findings are presented.

Literature review

All the studies found in the review focus on the effects of work on the health and development of children and adolescents, and on how it affects their cognitive, academic and social development. It is important to note that most of them state that poverty and other vulnerabilities are determining factors that lead to an early participation of children and adolescents in the labor market, and that starting working at an early age has a negative impact on their social development, since it seriously affects their formative stages of development and it does not have an actual effect on the satisfaction of their basic needs. 7 Likewise, most studies agree that this phenomenon mostly occurs in rural areas of both Colombia and Latin America, with a greater presence of male working children and adolescents who are responsible for carrying out activities related to the household economy, while female children and adolescents are usually in charge of domestic work. In general, these children and adolescents are unskilled workers who help their families by performing tasks such as the application of fertilizers, agrochemicals and pesticides, which are activities where they are exposed to significant risks. 8

Some factors that have been proposed to be associated with the occurrence of this phenomenon include poverty, cultural aspects, gender differences, the quality of education, family dynamics and the notion that parents have regarding work as a formative process for their children, since it has been culturally accepted that it provides them with a sense of responsibility and autonomy and helps them to achieve emotional maturity. 8,9

A fundamental factor for the occurrence of child labor, especially in rural areas, is that there is not a clear distinction between productive and reproductive labor, and therefore children and adolescents start helping in their household by doing housework or agricultural production tasks from an early age, since in these contexts most of the times education is associated with work and both converge in a unique process. 7

The Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO) and the ILO state that child labor in agriculture is a way of reproducing poverty across generations, and that agriculture is one of the economic sectors with the highest amount of risk factors to the health and physical and psychological integrity of children and adolescents. 10 In addition, most of the people working in agricultural crops live in rural areas and carry out these activities within a household economy or a small family farming context.

Angarita-Fernández 11, in a literature review on working conditions in countries such as USA, India, Australia, Canada, among others, reported that when compared with other industries, the agricultural sector showed the highest rates of occupational fatal injuries, a situation that is worsened by the fact that these accidents occur in family-owned farms where agricultural crops related work is carried out by the very family members, and in many cases, these activities are performed in an informal economy context.

Some studies 2,7,8 have described a concern regarding the scarcity or lack of public policies on child labor; likewise, they have noted that the constantly increasing child labor rates seriously affects children and adolescents' development and makes the socioeconomic gap between working and non-working children and adolescents bigger. Similarly, other studies 8-12 have shown a concern regarding the lack of regulations on child labor.

Regulations on child labor

Child labor has been an issue of great interest for international organizations that, in order to provide protection for children and adolescents, have established several declarations and conventions aimed at favoring the provision of protection, education and development opportunities for this population, as well as eradicating child labor. 12

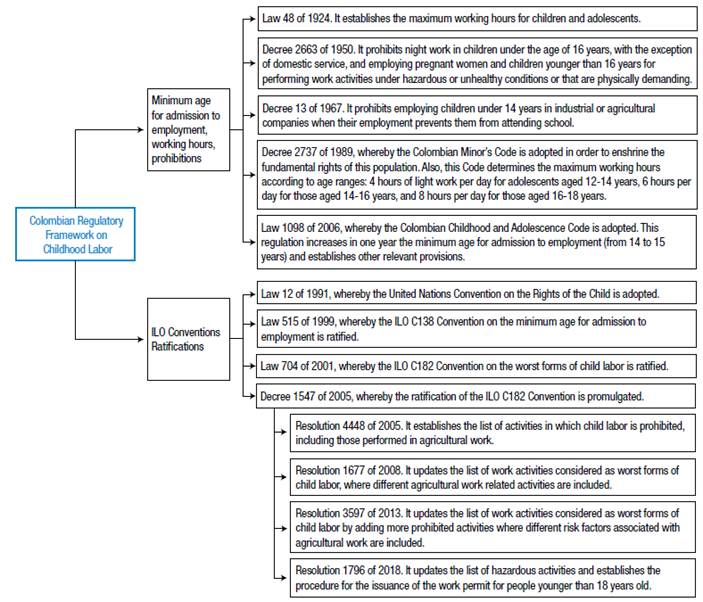

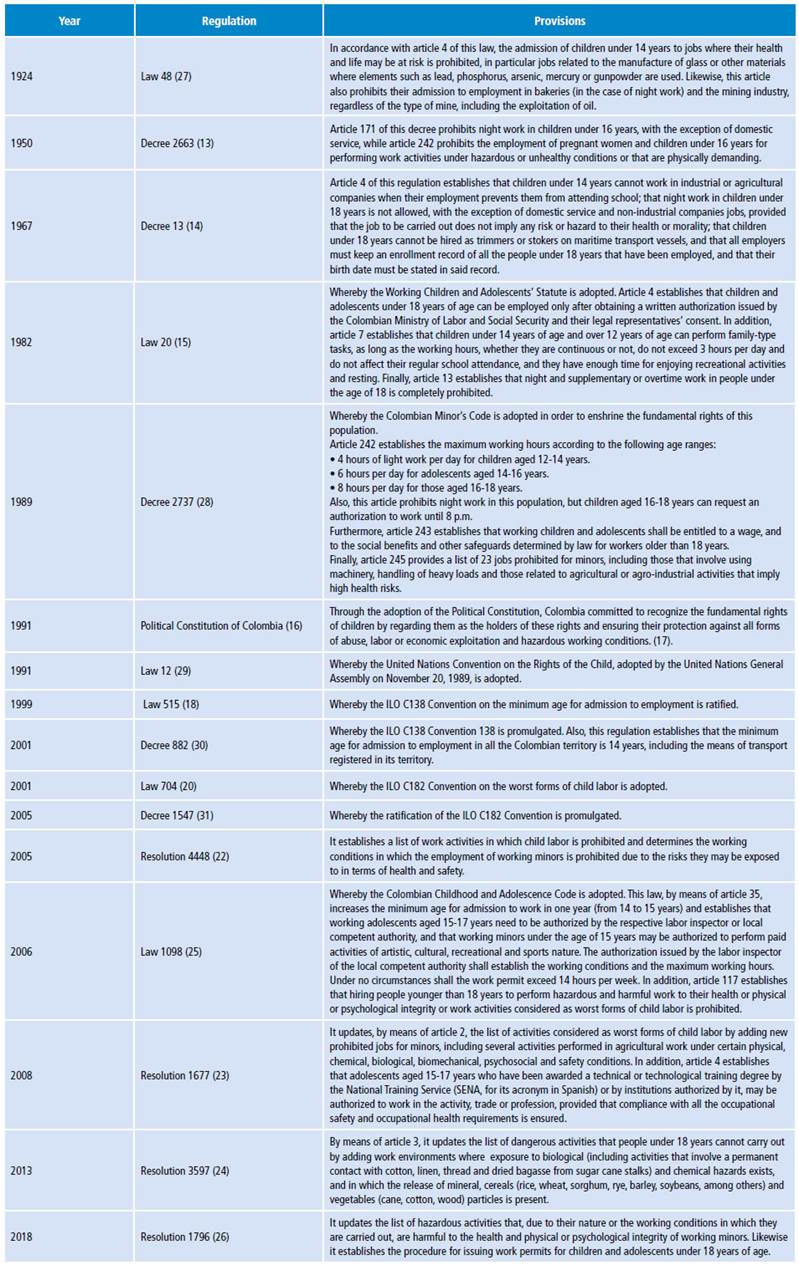

In Colombia (Figure 1 and Table 1), a regulatory framework on child labor was first established with the issuance of the Colombian Labor Code in 1950 13, and then it was updated with the adoption of Decree 13 of 1967. 14 Later, by means of Law 20 of 1982 15, a specific legislation on child labor was established, as well as the types of work in which working children and adolescents participation was prohibited.

ILO: International Labor Organization. Source: Own elaboration based on 13-16,18,20,22-31.

Figure 1 Colombian regulatory framework on child labor.

Table 1 Summary of the contents of the Colombian regulations on child labor.

ILO: International Labor Organization

Source: Own elaboration.

With the adoption of the Political Constitution of 1991 16, Colombia was declared as a State under the Rule of Law, and therefore the Colombian State committed to recognize the fundamental rights of children by guaranteeing the necessary conditions for their comprehensive development and ensuring their protection against all forms of abuse, labor or economic exploitation and hazardous working conditions. 17

In 1999, Colombia ratified the ILO C138 convention on the minimum age for admission to employment 18 through the adoption of Law 515. 19 Then, by means of Law 704 of 2001 20, the ILO C182 Convention on the worst forms of child labor 21 was also ratified. In 2005, Resolution 4448 of 2005 22 listed the activities in which child labor is prohibited and determined the prohibited working conditions for minors, including activities carried out in the agricultural, livestock, hunting and forestry sectors. The contents of this resolution were updated in 2008 and 2013 with the issuance of resolutions 1677 23 and 597 24, respectively.

In 2006, the Colombian Childhood and Adolescence Code (Law 1098) was adopted. 25 This regulation increased in one year the minimum age for admission to employment (15 years) and established that working adolescents aged 15-17 years need to be authorized by the respective labor inspector or the local competent authority. This code also prohibited hiring people younger than 18 years to perform hazardous and harmful work.

Finally, in 2018, the Colombian Ministry of Labor, through the issuance of Resolution 1796 26, updated the list of activities that are hazardous and harmful to the health and physical or psychological integrity of children and adolescents. In said list the prohibition of several activities performed in agricultural work under certain physical, chemical, biological, biomechanical, psychosocial and safety conditions was established; however the list of prohibited work activities for child workers established in Resolution 4448 22 was not included in this regulation.

Main findings of the fieldwork

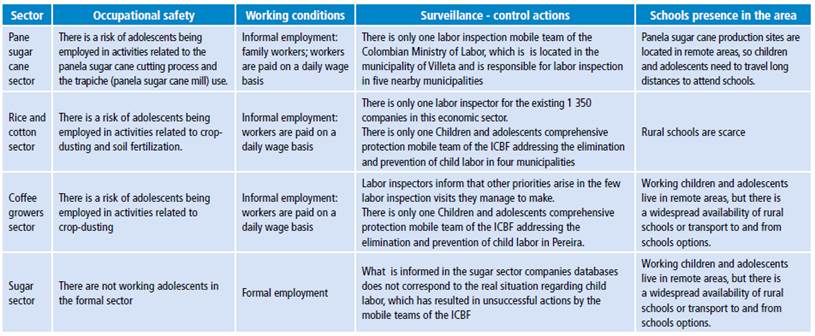

Based on the categories that were established for systematizing both secondary data and the information obtained from the interviews (Table 2), several aspects associated with the characteristics of the agricultural sectors analyzed here and that influence the participation of working children and adolescents in these sectors were evidenced. Table 2 was made after classifying the semi-structured interviews and comparing the response tendencies of all interviewees; it should be noted that some perceptions of the interviewees might not be included.

Panela sugar cane sector

Panela sugar cane production is characterized by the employment of family workers. In addition, in harvest season workers are hired under informal working conditions, a situation that is facilitated due to the lack of government surveillance and oversight bodies in these areas.

Likewise, the lack of occupational health and occupational safety practices in this sector has resulted in a high rate of occupational accidents with severe consequences such as amputations. Most of the amputees who were interviewed stated that they lost their limb when they were working children or adolescents. This situation is worsened by the absence of health care centers to provide timely medical attention when these accidents occur.

Cotton and rice sectors

In the cotton and rice production sectors, work is mainly automated, thus labor recruitment is not that high and all workers are hired within a formal employment framework.

Surveillance and control actions carried out by labor inspections offices, family welfare agencies, local ministries of health and children and adolescents comprehensive protection mobile teams of the ICBF are scarce. In the case of the municipality of El Espinal (city where the main production of rice and cotton takes place), there was only one labor inspector responsible for more than 1 350 existing companies in this sector, while the mobile team of the ICBF was composed of only two people, who were in charge of serving more than 100 000 inhabitants.

On the other hand, there is not available information on the working conditions in the agricultural sector in this region, but there are work environments in which children from extremely poor and vulnerable families are forced to work as pickers, which is a form of begging.

Despite formal employment is general in these agricultural production sectors, given the poverty conditions found in the areas where these industries are located, the emergence of homeless families that live in "zorras" (horse-drawn vehicles), which they also use for going to agricultural crops and harvesting cotton and rice is a normal phenomenon. This scenario makes it more difficult for official institutions to monitor agricultural work in these sectors, thus children and adolescents from these homeless families are left out of the education system, since their right to access education and decent housing is violated. In short, the lack of information on the working conditions in the area and of institutional infrastructure does not allow preventing these child labor practices by making timely interventions.

Sugarcane sector

Most of the employment in the sugar cane sector in the area where fieldwork was conducted is formal. The formalization of work in this sector, which is a result of multiple meetings and agreements between labor unions and sugar cane growers associations, has made possible the elimination of child labor in sugar cane production. However, outside the sugar mills formal employment scenario, there are several social problems regarding sugar cane cultivation. According to the interviews made to members of ASOCAÑA, in the south region of the department of Valle there are 1 020 families whose economic activity consists of stealing sugar cane from sugar refineries, and that most of children and adolescents in these families do not attend schools at all, for they live a nomadic lifestyle as their parents constantly move from one place to another within the thousands of hectares of sugar cane crops. 32

Coffee growers sector

In this sector most of workers are in informal employment conditions and they are paid on a daily wage basis. However, thanks to the joint effort and coordinated actions carried out by all the organizations that are part of the coffee production sector to minimize child labor, there was no evidence of working adolescents in this industry.

Most of coffee plantations are run within a family based economy model, so that children and adolescents from these families are asked to help in different activities related to the coffee production process, mainly administrative like tasks. Somehow, in the harvest season a lot of workers are hired under informal employment conditions, so, during this time children and adolescents may be hired.

It is worth noting that thanks to the Escuela Nueva (New School) program, which has been promoted by the Coffee Growers Committee of the Department of Caldas, an integration between the education system and the coffee production sector, particularly in the coffee plantations, has been possible, which allowed children and adolescents to access administration training programs that have enabled them to organize the production process in the plantations through the implementation of new technologies, which in turn has allowed them to help their families without putting their health or schooling at risk. 33

Discussion

Early admission of children and adolescents to employment is a widespread phenomenon that occurs in periphery, semi-periphery and core countries. Therefore, this is a problem of serious concern for all societies around the world, as it has multiple social, economic, cultural and health consequences.

Most of child labor occurs in the informal sector of economy, where occupational exposure is higher. The fact that this phenomenon is more frequent in informal economy or "suburban" areas and that most of the work performed by children and adolescents includes activities considered as the worst forms of child labor does not allow accessing real or close data on this situation in Colombia. Likewise, the Colombian health system does not have accurate data on the effects of early occupational exposure in the health condition and quality of life of this population.

Thanks to the fieldwork conducted here, it was possible to confirm that, as in the case of other countries 12, children and adolescents work informally, while in the industrial production and formal economy sectors there is no evidence of child labor. In this sense, unpaid family labor was mainly found in the panela sugar cane and the coffee growing sectors, provided that agricultural work in these sectors occurs within a family subsistence context.

Crop-dusting is one of the hazardous jobs that children and adolescents perform in the coffee growing sector, while in the case of panela sugar cane production, they are employed to carry out activities related to the panela sugar cane cutting process, the handling of the trapiche (panela sugar cane mill), and the driving of animals necessary for the trapiche to work, tasks that involve very dangerous mechanical processes.

Regarding admission to informal employment in the cotton, rice and sugar cane production sectors, children and adolescents are recruited to work informally not on the very crops, but in nearby areas. In addition, in the sugar cane sector, children and adolescents are asked by their parents to steal sugar cane while being transported from crops to sugar refineries, an illegal and dangerous activity that exposes them to public risk situations such as armed confrontations with the police and the owners of the crops.

Furthermore, these work environments are characterized by a scarcity of labor inspectors (who are essential for the proper implementation of control and surveillance measures), a situation that results in the lack of sufficient human resources to make labor inspection visits to all the companies in the coffee growing sector. This condition restricts the implementation of interventions that must be made by government institutions to address the surveillance and monitoring of child labor, as labor inspectors are responsible for issuing work permits for children and adolescents, but according to them, they rarely issue these permits as they are aware it is impossible for them to monitor whether the working conditions informed in the work permit request are met or not during the employment period. However, in the case these permits are granted, they are only applicable for the industrial sector and formal economy employment, which means that child labor still occurs in informal economy without government supervision and control measures.

Taking this into account, it is possible to say that labor inspection and control actions in these areas are limited by the lack of resources, both financial and human, which produces a limited institutional context, where the State's capacity to guarantee the rights of children and adolescents is restricted. Similarly, the institutions responsible for securing the welfare of this population are overwhelmed by the fact that working children and adolescents in the agricultural sector are scattered in large areas, a situation that is worsened by the scarce resources they are allocated to send mobile labor inspection teams to work with this population.

Regarding schools presence in rural areas -a fundamental factor for securing the social welfare of children and adolescents-, there are several issues that need to be addressed, since the adverse geographical conditions, the fact that rural populations are dispersed, and the absence of means of transport makes attending school a real challenge.

Despite this discouraging scenario, the coffee growing sector is an exception, as in these areas, as seen in the case of the department of Caldas, there is a large presence of schools that are part or have been integrated to the New School program 34, which allows the provision of training to children and adolescents on the different coffee production processes by combining theory and practical work, and therefore they will eventually be sufficiently trained to help their parents to face the new challenges in the sector, mainly in administration and financial aspects, and to plan their lives in an agricultural work context.

Conclusions

Child labor in Colombia, especially in the agricultural sector, needs to be paid more attention by government institutions, in particular by those involved in the education sector.

The studies found in the literature review conducted here report a concern regarding the scarcity or total lack of public policies on child labor; likewise, they have noted that the increase in child labor rates seriously affects children and adolescents' development and makes bigger the socioeconomic gap between working and non-working children and adolescents. Similarly, a concern regarding the lack of regulations on child labor is also reported.

Taking this into account, further studies addressing child labor characteristics in the agricultural sector in Colombia are required to obtain sufficient elements to develop coordinated actions involving the State, the business sector and society in general in order to address this phenomenon effectively.

The Colombian regulatory framework on child labor includes some of the standards and policies that have been internationally established in this regard, somehow it still needs to be strengthened with the development and implementation of public policies aimed at making possible a clear intervention of the determinants of child labor and, this way, achieve its eradication. The fact that in Colombia there is a regulation that lists the activities that are hazardous to children and adolescents and that prohibits their recruitment to carry out said activities is not enough, as in order to properly deal with the structural causes leading to child labor it is necessary to fully understand this phenomenon in rural and urban settings.

Since Colombia is a country where institutional asymmetries are found, the debate on child labor in the different agricultural sectors covered here should be based on a regional perspective, for in multiple aspects each region has its own particularities.

As mentioned above, rural areas pose important challenges in terms of access to education by children and adolescents, since the absence of schools in these areas, mainly in rice, cotton and sugar cade production regions, deprives them from their right to education. On the contrary, in the coffee production areas, there is a widespread availability of schools, in particular in the department of Caldas, which is the result of the implementation of the New School strategy, a program that integrates knowledge and training related to the coffee production process into school education; this way school dropout rates are reduced and adolescents are prepared for future participation in agricultural projects, besides through this program they are given the possibility to plan a project of life in the context of agricultural work in rural areas.

The different realities of the economic sectors and regions where child labor occurs imply that the eradication and prevention of child labor, in addition to being issues that need to be addressed from a regulatory perspective, require government institutions to work together, as well as with the communities of these regions, to create and adjust a social services offer that makes possible to ensure the restoration of the rights of working children and adolescents and the prevention of new cases of admission to employment in this population.

The present article derives from the findings made in the child labor in the Colombian rice, coffee, cotton and sugar cane production sectors component of the cooperation agreement No. 290 entered into by the Colombian Ministry of Labor and Universidad Nacional de Colombia on November 19, 2015.