Introduction

Quality of work or professional life

The terms quality of life at work, quality of work life (QWL) or quality of professional life (QPL) emerged in 1972 1 from the heterogeneous and imprecise conception of two interrelated perspectives: on the one hand, the micro perspective, which is psychological and focuses on the health and well-being of the worker, and on the other, the macro environment and working conditions, which focuses on organization, productivity and efficiency. 2

QWL is a complex, integrating and comprehensive concept 3 that affects well-being, alludes to the perception of work experience in subjective (how it is perceived) and objective (safety, occupational hygiene) conditions, and includes psychological, contextual and interactive processes with other people and with the environment. In this regard, Segurado-Torres & Agulló-Tomás 2 emphasize the need for evaluating psychological and subjective components, quality of the environment, satisfaction, health and perceived well-being.

From the worker's perspective, QWL stresses individual practices perception, motivation and level of satisfaction, so that participation, decision making processes, how to engage into the organization, work facilities and working conditions are aspects to be considered when attention needs to be focused on how organizations work. Likewise QWL seeks to make work scenarios more humane and to design safe, healthy, ergonomic, effective, democratic and participatory conditions in order to promote professional and personal growth.

Locke 4, also quoted by Chiang-Vega & San Martín-Naira 5, defines QWL as a pleasant and positive emotional attitude according to the self-perceived work experiences, or as an emotional response to the work environment; it is influenced by personal and work expectations, needs and aspirations delimited by individual history.

Perceived quality of work life

According to Toro-Álvarez 6, perceived quality of work life (PQWL) includes technological, organizational, administrative and socioeconomic aspects that contribute to the satisfaction of needs. It is linked to job satisfaction and organizational climate, includes commitment to work and organization, presupposes affective (feelings) and cognitive (beliefs) components 7, and has an impact on personality, sociodemographic characteristics and employment status.

PQWL is outstanding when staff members meet their needs 8, as it is conditioned by personal characteristics that affect vulnerability to take on, cope with and adapt to working conditions. It arises from satisfying the needs for motivation and education 9, and increases in scenarios that generate high levels of motivation (wanting to act) and training (being able to act).

In this sense, PQWL is the product of the balance between the demands of a challenging, vigorous and complex work activity, and the ability to face them to achieve the best professional, family and personal development 10; it also generates a sense of well-being by perceiving harmony between demands, responsibilities, resources of the organization, and psychological and relational work skills to respond to them. 11 Job satisfaction requires balance between job demands and resources 12, so the QWL is positively related to motivation, managerial support and, conversely, workloads.

Individual PQWL indicators assess how the worker experiences and performs at work: job satisfaction and motivation; expectations, attitudes and values; and the level of involvement and commitment 2. Personal characteristics are conditioning factors for QWL and affect the vulnerability to assume, face and adapt to working conditions.

In this research, PQWL was evaluated as a feeling of well-being resulting from the perceived harmony between work demands and the psychological, organizational and relational resources to face them. Emotional intelligence (EI) and coping strategies (CS) are included as personal variables to consider. In other words, this work analyzed the association between EI, CS and PQWL.

Emotional intelligence

EI is a pragmatic perspective of emotions, as it integrates emotion and cognition and emphasizes psychological effectiveness according to non-cognitive personality and adjustment models. 13,14 Another aspect focuses on cognitive capacity, intelligence, processing and regulation of information. 15,16

For Bar-On 14, EI integrates non-cognitive skills and competences that influence active and successful coping and adaptation to the demands and pressures of the context. The author highlights five capacities: intrapersonal, interpersonal, adaptability, stress management and mood. 14 On the other hand, Gabel-Shemueli 17 states that EI is a predictor of adaptive potential to contextual pressure and influences achievement, response to job stress and assimilation of organizational culture; it is a predictor of job success and behavior. 17.

Current work contexts give special importance to EI components such as work interaction, teamwork, adaptation to change, initiative, empathy and communication, interaction, motivation and leadership skills, as well as spaces for self-reflection, awareness, self-criticism and self-confidence. In this regard, Goleman says that "the rules for work are changing. We're being judged by a new yardstick: not just by how smart we are, or by our training and expertise, but also by how well we handle ourselves and each other." (18, p17)

Workplace interaction and leadership

Leadership affects effectiveness, efficiency, competitiveness and organizational prosperity; it relates to team cohesion, motivation and commitment; it affects the organization, and the health and well-being of workers; and it enhances healthy and encouraging work environments. 19. Leaders are emotional guides 20 whose affective bond transcends the workplace, as they contribute to performance and avoid stagnation with low anxiety and aversion by positively channeling emotions.

Strategies for coping with work-related stress

CS are personal resources of a physical, emotional, cognitive and social nature that generate greater internal and external control and decrease vulnerability to stress. 21 The CS based on assertiveness and cooperation reduce the incidence of conflicts and generate job satisfaction and higher organizational productivity; they also influence the response to stress, confidence among the team, the strength of the social network, and the achievement of employment objectives.

If CS are not collaborative, the quality of team interaction decreases, which constitutes a risk to perpetuate relational conflicts that affect job satisfaction, productivity and quality of service. 22

With all of this in mind, the objective of this research is to investigate the employment location of the graduates of a Manizales university between 2012 and 2013, and the correlation between PQWL, EI and CS.

Materials and methods

This was an analytical cross-sectional study, which took into account a universe of1 254 undergraduate graduates from a university of Manizales during the years 2012 and 2013. The instrument was sent to the entire population in digital format and included an informed consent form. Only 149 people (12%) responded despite explanatory and motivational emails.

The quantified variables were: academic program, sex, age, socioeconomic level, origin, place of residence, employment location, concordance between training received and current work demand, PQWL (CVP35 scale), EI (TMMS-24 scale), and stress coping type (CRIY scale).

CVP35 scale

Using 35 questions, this instrument measures PQWL through responses given on a scale from 1 to 10: 1 and 2 for nothing; 3, 4 and 5 for something; 6, 7 and 8 for a lot; and 9 and 10 for quite a lot. CVP35 contains 4 subscales: managerial support, workload, intrinsic motivation and overall perceived QPL; it was validated for the Spanish ]population by Martín et al.23 Nevertheless, experts such as Fernandez-Araque et al.11 do not agree on the associated dimensions and have identified affinity around three groups: workload or demands, intrinsic motivation and managerial support, and the categories quite a lot, a lot, some and none.

Workloads or demands

Workers' perception on the demands of their position is associated with the workload, speed, quality, pressure, fatigue and discomfort generated by a high volume of work. This aspect involves conflicts with colleagues, reduction of working time, overload of responsibilities, unpleasant interruptions and physical fatigue.

Intrinsic motivation

It is related to the personal motivation for professional satisfaction. The type of work activity, generated motivation, creativity, demands and training support from the work team and the family are associated factors.

Managerial support

This aspect involves the emotional support provided by managers: recognition of effort; opportunity to be promoted and expressing feelings and needs; salary satisfaction; support from bosses and colleagues; feedback on work results; autonomy; variety; and the possibility of creativity.

TMMS-24 scale

The scale measures EI and is based on the Trait Meta-Mood Scale (TMMS) by Salovey et al.24 This instrument contains three key dimensions, each with 8 items, while the categorization has three levels: clarity should be improved, adequate clarity and excellent clarity. This has been validated by Fernández-Berrocal et al.25, Espinoza-Venegas et al.26 and Durán-Cofré 27, the latter in a version of 48 questions (TMMS-48).

Moos' Coping Responses Inventory-Youth (CRI-Y)

This is an abbreviated version of the Coping Responses Inventory-Youth 28-30 and has 48 items grouped into 8 dimensions. Ongarato et al.31 developed and validated a version with 22 questions grouped in 4 scales in Argentina with high school and university students.

Statistical analysis

Variables measured on a nominal scale were obtained using frequency tables and 95% confidence intervals, while measures were expressed at ratio scales using mean, standard deviation and 95% confidence intervals. The correlation between variables measured on a nominal scale was tested by means of the χ2 statistic, calculating Pearson's Chi-square and its corresponding significance. Statistical inference analyses were performed with a level of significance of α=0.05. Missing values were omitted from the calculations.

Ethical considerations

This research was approved by the Research Office of the Universidad de Manizales and its Bioethics Committee through minutes without consecutive number issued on April 16, 2018. All the principles of the Helsinki Declaration were respected. 32

Results

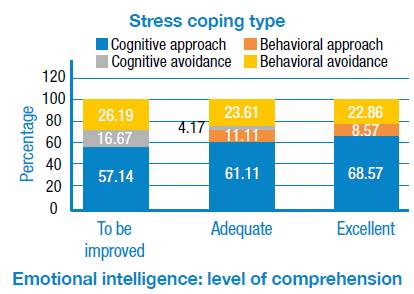

The survey was responded by 149 graduates with an average age of 28 years: 63.1% were women, 39.6% were classified in socio-economic level 4 -middle class-, 60.4% were from Manizales, 55.1% resided in this city, 79.1 % studied during the day, 5 5.7% graduated in 2013, 15.5% were graduates from the Psychology program, and 88.6% worked; of the latter, 51.7% had a full-time job. When analyzing concordance between theoretical training and some variables, it was good for 37.6% regarding their work activity, good for 36.9% regarding the applied training, and excellent for 36.2% regarding personal training (Table 1).

Table 1 Demographic variables of the population of graduates participating in the study.

Source: Own elaboration.

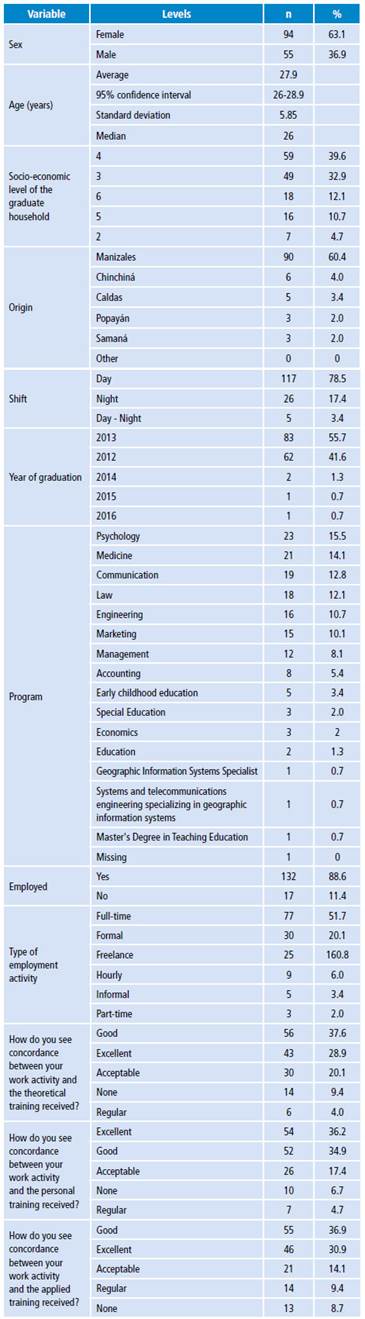

Tables 2, 3 and 4 show the results for each of the instruments applied. Regarding internal consistency, the subscales of the CVP35 questionnaire had a Cronbach's α of0.930 in managerial support, 0.890 in workload perception and 0.883 in intrinsic motivation. Globally, this scale presented a Cronbach's α of 0.936.

Table 2 Results on quality of work life in graduates from a university of Manizales in the years 2012 and 2013. CVP35 Quality of Life Questionnaire.

Source: Own elaboration.

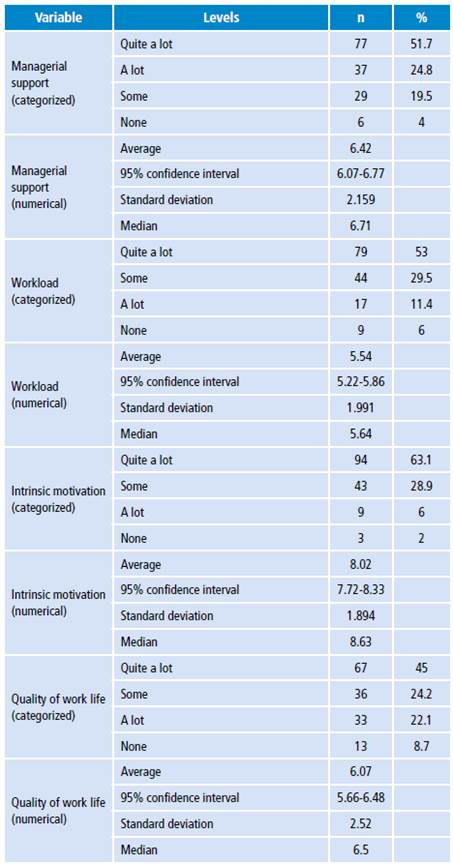

Table 3 Results on emotional intelligence of graduates from a university of Manizales in 2012 and 2013. Questionnaire TMMS-24 of emotional intelligence.

UL: upper limit; LL: lower limit.

Source: Own elaboration.

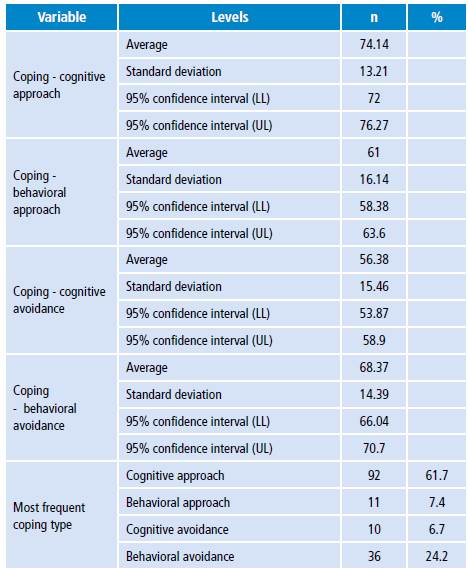

Table 4 Results on emotional intelligence of graduates from a university of Manizales in 2012 and 2013. CRI-Y scale of coping with stress.

UL: upper limit; LL: lower limit.

Source: Own elaboration.

In the TMMS-24 questionnaire, the overall consistency of the Cronbach's α was 0.940, with a subscale of perception of 0.944, a subscale of comprehension of 0.946, and regulation of 0.916. The questionnaire had a high internal consistency that guaranteed the validity of the results and suggested consistent responses from participants and not "random" responses.

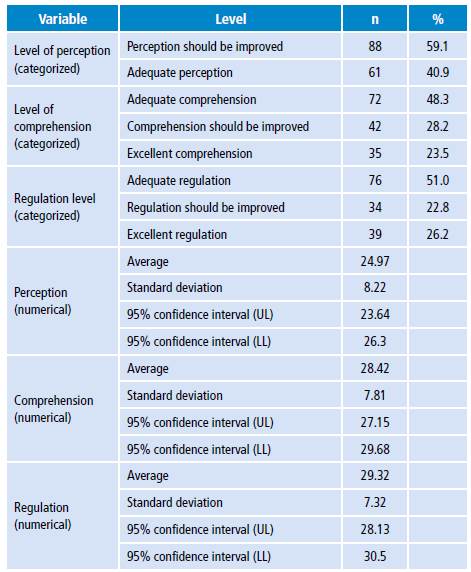

The internal consistency of the CRI-Y coping scale was 0.868. This showed that avoidance strategies, whether behavioral or cognitive, tend to minimize the effects of the stressful situation, which may be beneficial to face transient stress, but not work tension, as concluded by several longitudinal studies. 33

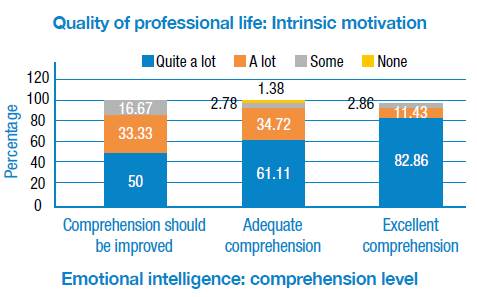

The level of EI comprehension subscale of the TMMS-24 questionnaire has a strong correlation with the CVP35 subscales workload (p = 0.016), managerial support (p = 0.025), and intrinsic motivation (p = 0.002). The correlation between the level of comprehension and intrinsic motivation is shown in Figure 1.

Source: Own elaboration.

Figure 1 Correlation between the emotional intelligence subscale and level of comprehension, and the professional quality of life subscale and intrinsic motivation.

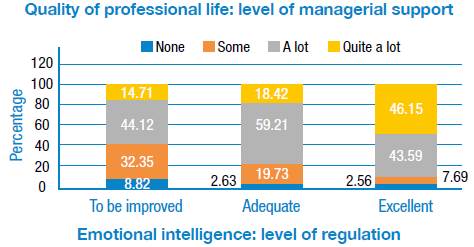

Strong correlations were also found between the EI subscale level of regulation and some subscales of the CVP35 questionnaire: managerial support (p=0.003) and intrinsic motivation (p=0.001). Figure 2 shows the correlation between these last two variables.

Source: Own elaboration.

Figure 2 Correlation between the emotional intelligence subscale and level of regulation, and the managerial support subscale of the professional quality of life questionnaire.

The EI level of perception subscale only has a strong correlation (p=0.025) with the QWL subscale of the CVP35 questionnaire. Graduates with an adequate level of perception report 57.38% of QWL in the "a lot" category, figure that drops to 36.36% among those who should improve their perception.

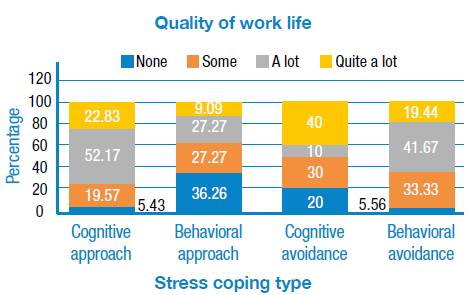

Three of the CVP35 subscales are significantly correlated to the stress coping type (CRI-Y Questionnaire): managerial support (p=0.021 ), intrinsic motivation (p=0.000) and QWL (p=0.009). Figure 3 shows the variation in the perception of the Quality of life at work subscale of the CVP35 questionnaire with the stress coping type.

Source: Own elaboration.

Figure 3 Perceived quality of work life according to coping stress type in graduates from a university of Manizales.

The correlation between coping type and the three subscales of the TMMS-24 questionnaire, through χ2, presents: perception level p=0.059, comprehension level p=0.027 and regulation level p=0.075. Figure 4 illustrates the correlation between coping type and level of comprehension (p=0.027). Coping through cognitive approach gradually increases from 57.14% in graduates who should improve their comprehension, to 68.57% in those who have excellent comprehension.

Discussion

The results show that the vast majority (88.6%) of respondents are employed -51.7% full-time-, which coincides with the figure of 80.7% of employment in university graduates according to the Observatorio laboral para la educación en Colombia (Colombian Labor Observatory for Education). 34

QWL was perceived as "quite a lot" or "a lot" by 67.1 %; managerial support as "quite a lot" or "a lot" by 76.5%; workload as "quite a lot" or "a lot" by 64.4%; and intrinsic motivation as "quite a lot" or "a lot" by 93%.

Regarding EI, perception should improve for 59.1%; this influences the QWL, EI component that shows the most inadequate behavior. In addition, 71.8% and 77.2%, respectively, show a comprehension level and regulation level between adequate and to be improved. In relation to the CRI-Y scale for stress coping, 61.7% had adequate coping by cognitive approach.

The CVP35 questionnaire has been used especially for the health sector, in this research, graduates linked to this area constitute 14.2%of the population (Table 1). Garrido-Elustondo et al.35, in a study with 1 003 primary care professionals in the Area 7 of Madrid, identified workload perception of 6.09, managerial support perception of 5.1, intrinsic motivation of 7.56, and PQWL of 5.45. In general, the results obtained in this research are better, evidencing an average QWL of 6.07, perception of managerial support of 6.42, and intrinsic motivation of 8.02. The perception of workload is lower in this research: 5.54.

Jubete-Vázquez et al.36, in a study with 1 324 primary care professionals in Madrid, obtained the following scores: 4.66 in perception of QWL, 4.66 in perception of managerial support, 7.16 in intrinsic motivation, and 6.45 in perception of workload. Again, and in all dimensions, the present study obtained better results for QWL.

Fernández-Araque et al.11 analyzed the QWL in 104 nursing professionals in Soria (Spain) using the CVP35 questionnaire and obtained scores of 5.68 in perception of the QWL, 7.85 in perception of intrinsic motivation, 4.9 in perception of managerial support, and 5.71 in average perception of workload. These values, with the exception of workload perception, are very similar to those obtained in this study.

Furthermore, Hernández-Armegond 37, through the CVP35, analyzed the QWL of 56 nursing professionals from Teruel (Spain) and found a score of 6.75 for QWL perception, 7.85 for intrinsic motivation, 6.06 for managerial support, and 5.83 for workload, which are also similar to those obtained in this research.

Sosa-Cerda et al.38 investigated the QWL through the CVP35 questionnaire in 311 nurses of the Mexican Institute of Social Security in San Luis Potosí (Mexico) and found a perception of "quite a lot" in 69% in the QWL domain, 62.1% of "quite a lot" in managerial support, 55.3% of "a lot" in intrinsic motivation and 56.9% of "some" in workload. This study found a perception of 45% in the category of "quite a lot" in QWL, 51.7% of "quite a lot" in managerial support, 63.1% of "a lot" in intrinsic motivation and 53% of "quite a lot" in workload, values that in some cases are lower and in others higher than those obtained in the aforementioned study.

Puello-Viloria et al.39 described the perception of QWL through the CVP35 questionnaire with 34 nursing workers in Santa Marta (Colombia) and obtained a score of 4.3 in perception of managerial support, 6.7 of intrinsic motivation and 4.4 of workload. In this study, forthese dimensions, values of6.42,8.02 and 5.54, respectively, were obtained; these are better scores than those reported in the previous study, although they show greater perception of workload.

Consequently, it can be concluded that the values obtained in this research for the perception of QWL, in general, are similar to those obtained in other population studies in which the CVP35 questionnaire was used.

Regarding this same questionnaire, Sánchez-González et al.40 and Fernández-Araque et al.11 found that intrinsic motivation and managerial support increase PQWL. Similarly, Albaneside Nasetta 41 researched PQWL in health workers and concluded that support from superiors promotes good performance and quality of average life.

Only one study, Contreras et al.42, estimated the internal consistency (Cronbach's a) of the CVP35 questionnaire; it was carried out on 38 employees of a cancer center in Bogotá (Colombia). The a estimated for the subscales of the questionnaire were as follows: managerial support: 0.92; workload: 0.762; intrinsic motivation: 0.792; and overall: 0.893. In this study, the a calculated are 0.930, 0.890,0.883 and 0.936, respectively, higher scores than those reported by Contreras et al.42 These values mean that the questionnaires were responded adequately by the participants and the data obtained are very reliable. The values found in the Contreras et al.42 study for the subscales were, in the same order, 5.37, 5.42 and 7.31 ; in this, research the values were higher in the subscales managerial support and intrinsic motivation, and lower in workload. In conclusion, the population participating in this study has a better perception of QWL in general.

Salvador-Ferrer 43 was the only study found that estimated a for the TMMS-24 questionnaire; its results were: perception 0.872, comprehension 0.779, and regulation 0.846, values that in the present study were 0.944, 0.946 and 0.916, respectively. In said study, the value obtained for the subscales of the TMMS-24 were, in the same order, 26.9, 25.43 and 27.08, which in the present work were 24.97, 28.42 and 29.32, respectively.

Emotional skills are related to leadership at the professional level, better teamwork skills and job satisfaction. The opposite situation, associated with poor management of emotional skills, affects health in general, as it has greater impact on professional attrition and generates greater stress, lower self-esteem and depressive components, as referred to by the state of the art on research with students of nursing by Espinoza-Venegas et al.26

The results of this study confirm these findings in several ways: graduates with high scores in the three subscales of the TMMS-24 questionnaire (levels of perception, comprehension and regulation) also have good scores in the QWL, as shown in Figures 1 and 2.

This correlation between EI and work performance can be synthesized as follows: the higher the emotional intelligence, the better the work performance; this result was also obtained by Enríquez-Argoti et al.44 Furthermore, Castaño-Castrillón & Páez-Cala 45 found a significant correlation between EI and academic performance in undergraduate students of the Universidad de Manizales (Colombia).

Other studies also identified a positive correlation between EI and QWL variables. For example, Tagoe & Quarshie 46, in a study with 120 nurses in Ghana, found a significant positive correlation between EI and job satisfaction, although this was not confirmed from a gender perspective; Ravikumar et al.47 investigated EI on 200 postgraduate medical students in Delhi (India) and found a positive correlation with perceived workload; finally, Yamani et al.48 conducted a study with 202 members of the Isfahan University of Medical Sciences in Isfahan (Iran) to measure their EI and work stress, and found that those with high EI had lower work stress.

In the present study, there is a significant correlation between stress CS and QWL, as shown in Figure 3. In this regard, Peña 49 tried to correlate QWL and stress CS in 46 employees of the private security services sector in Maracaibo (Venezuela), but found no significant correlation.

In the present study, a correlation was found between EI and CS: those with higher EI tend to face stress by cognitive approximation. Peiró & Rodríguez 19, Amutio-Kareaga 21, Srivastaga 50, Sy & Cote (51) and King & Gardner 52 also confirmed a positive association between EI and CS; Gómez-Coello 53 confirmed the association between EI and attitude towards change.

The difficulty of collecting the required sample was the main limitation of this study; for this reason, the results cannot be considered as representative of the graduate population of this university. Another limitation was the difficulty of conducting a research based on a survey and the reliability of the results, but the high values of the internal consistency coefficient (Cronbach's α) obtained in the employee questionnaires suggest that the participants responded conscientiously.

Conclusions

This study confirms the relevance of EI in the perception of QWL in the different professional activities carried out by recent university graduates. It also has a positive influence on CS in an increasingly stressful modern world, particularly for young professionals.

Despite the high perceived workload, graduates report managerial support, which contributes to intrinsic motivation and influences regulation, associated with effective management of positive and negative emotions. The QWL is influenced by perception as the ability to consciously differentiate one's emotions and recognize one's feelings.

Comprehension (cognitive-affective integration and assessment of the complexity of changes) is strengthened by identifying managerial support; thus, there is intrinsic motivation and high workload.

The relatively high level of adequate coping by cognitive approximation implies restructuring the meaning assigned to the event to involve a novel assessment that enables a positive emphasis; it is an active attitude, not passive or avoidant. The findings reported here suggest the relevance of perceiving managerial support, in this case, through regulation associated with the effective management of emotions, both positive and negative.

In university life, more importance should be given to EI, a relevant task of the student support units. In other words, comprehensive training in university students requires the inclusion of emotional competences in the different curricula in order to counteract the negative effects of work stress on their physical and emotional health, and this way to improve their perception of QWL in order to have a better work performance and a higher productivity when they enter the labor market.