Introduction

Orthodontists expect their patients to adequately follow their instructions in order to meet the treatment goals.1 Such instructions include meeting appointments, dietary care, pain management, modification (in form and intensity) of oral hygiene practices, among others,1-3 in order to help the patient adapt and get used to wearing devices such as braces, elastics, mini screws, archwires, etc.4,5 If the patient does not comply with these recommendations, the treatment goal may be seriously compromised and adverse events may occur.6,7

There are several definitions of adherence to treatment and terminology in this regard, both in English and Spanish, is diverse.8,9 Therefore, assessing treatment compliance and adherence of patients, especially in university clinics that treat high volumes of patients and have students in training, is an opportunity to recognize the factors associated with failure to comply and the basis for improving and achieving success.

Adherence to treatment can be approached from two perspectives, one that concerns medications (adherence to medications)10 and the other related to meeting the goals set for a specific treatment (adherence to therapy).11 In this sense, the definition of adherence that best fits the therapeutic perspective, in the authors' view, is the one promoted by the World Health Organization (WHO), which shows its multiple contexts.12 Based on this definition, it can be said that adherence to therapy in orthodontics is related to the patient following the instructions provided by the health operator with responsibility and to do so based on the patient's perception of the importance of orthodontic treatment and the benefits that the treatment brings to their health.

Large medical institutions with quality programs frequently evaluate adherence to the treatments they provide; however, little is known about this evaluation in university institutions, where specialized orthodontic training serves large volumes of patients and, therefore, the relationship between compliance with treatment goals and adherence to treatment is not clear.13

Although there are satisfaction studies of dental care in university clinics,14 studies on adherence in orthodontic schools are scarce. In this sense, it is important to have an instrument to measure adherence to orthodontic treatment in specialized training schools, where constant evaluation is key to good patient-centered service and to train professionals concerned with the quality of care.8

On the other hand, some authors state that there are numerous variables related to adherence to treatment,15,16 which include aspects specific to the person being treated, treatment, family, environment, health personnel and the relationships between them.17-19 WHO proposes five dimensions associated with the overall definition of adherence to treatment: social and economic factors, healthcare system-related factors, disease-related factors, therapy-related factors, and patient-related factors.12

It can then be considered that a tool for measuring adherence to treatment in the context of long-term care in university institutions requires including the dimensions established by the WHO within its structure.12 In this regard, the objective of this study was to validate, by means of an exploratory factor analysis (EFA) and a confirmatory factor analysis (CFA), an instrument to measure adherence to orthodontic treatment in dental clinics of dentistry schools where a large number of patients are treated.

Materials and methods

Study type

Quantitative study in which an instrument was validated to measure adherence to orthodontic treatment by means of an EFA and a CFA.

Study population and sample

The study population comprised all patients who underwent orthodontic treatment at the dental clinic of a university in Bogotá, D.C. and were treated by graduate students.

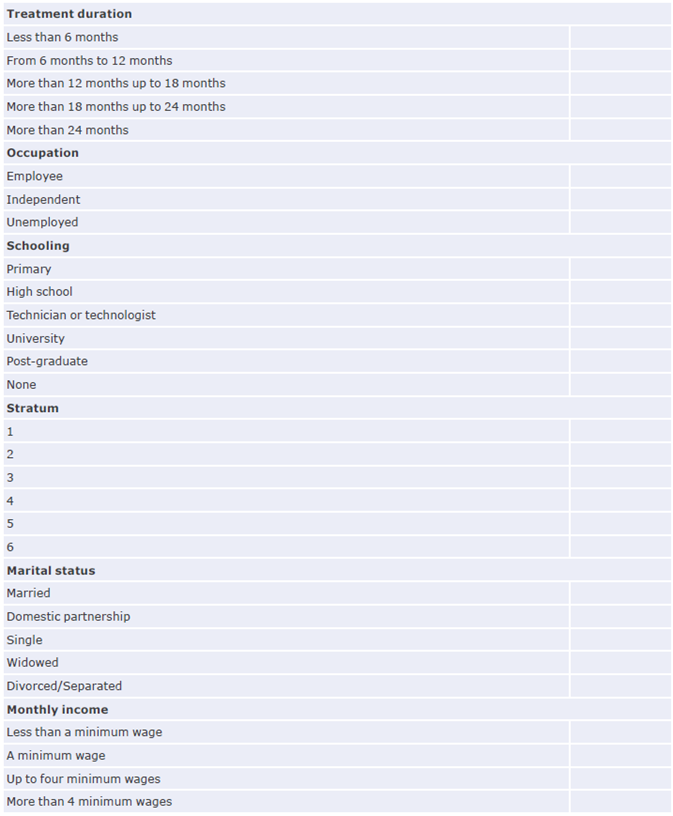

The final sample consisted of men and women of age and the following inclusion criteria were considered for selection: having been in treatment at the institution for more than six months at the time of answering the survey, being treated by orthodontic postgraduate students, and accepting participation in the study. Patients who had a situation that prevented them from responding to the survey and those who did not answer the questionnaire in its entirety were excluded. The questionnaire was administered to 654 patients, of whom 53 were excluded because they did not meet the selection criteria; thus, the final sample was made up of 601 patients.

To perform factor analyzes, the sample (n=601) was divided into 2 randomly selected groups using the SPSS software; thus, subsamples for EFA and CFA were made up of 202 and 399 patients, respectively. In both groups, the majority of participants were female (79.9% and 59.4%, respectively). The patients were between the ages of 18 and 57 years in the first group and between the ages of 18 and 62 years in the second group, which was considered to be consistent with the literature recommendations for EFA and CFA.20,21

Ethical considerations

The study took into account the ethical principles for medical research involving human subjects established by the Declaration of Helsinki22 and the standards for health research of Resolution 8430 of 1993 of the Ministry of Health of Colombia.23 The research protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Universidad Antonio Nariño according to Minutes 011 of February 14, 2018. Anonymity and confidentiality of the participants were preserved at all times.

Instrument

An instrument developed in 2017 by a group of orthodontists that included two of the authors of this article was used. It was designed to measure adherence to orthodontic treatments in patients treated in dentistry clinics of university institutions24 and was created based on the Delphi methodology. The instrument was reviewed by 11 expert judges and questions were selected using Aiken's V content validity coefficient and Lawshe's validity content ratio.25

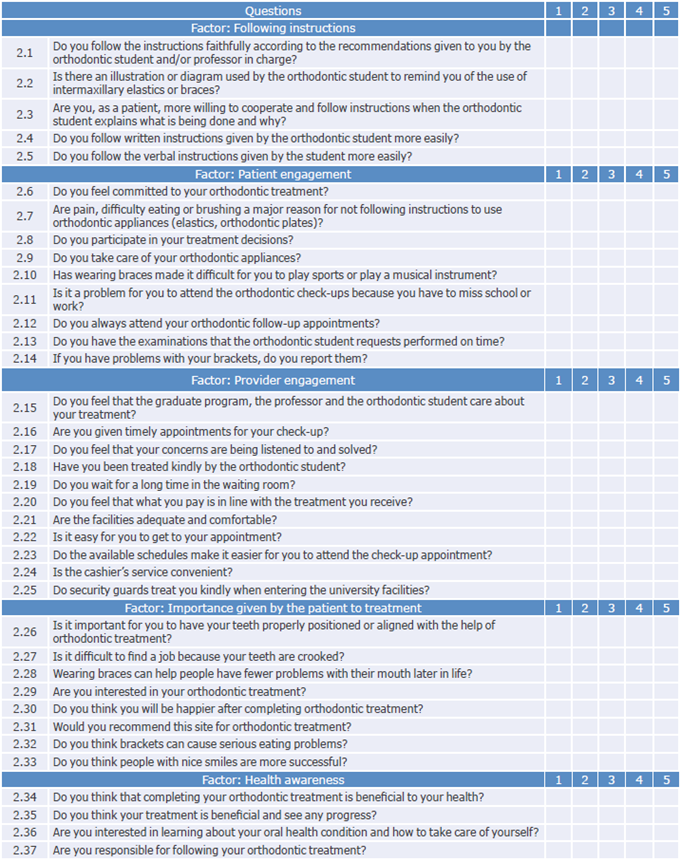

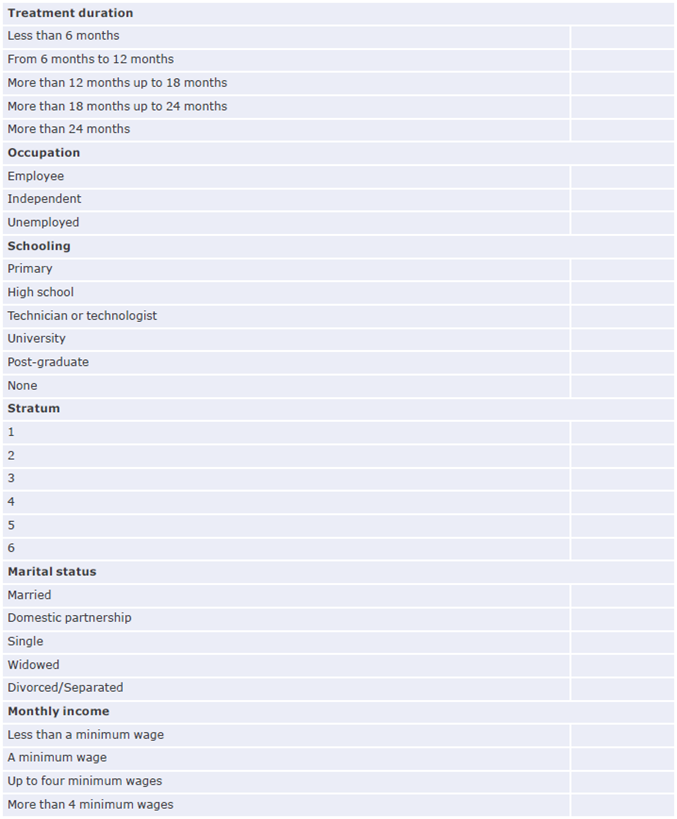

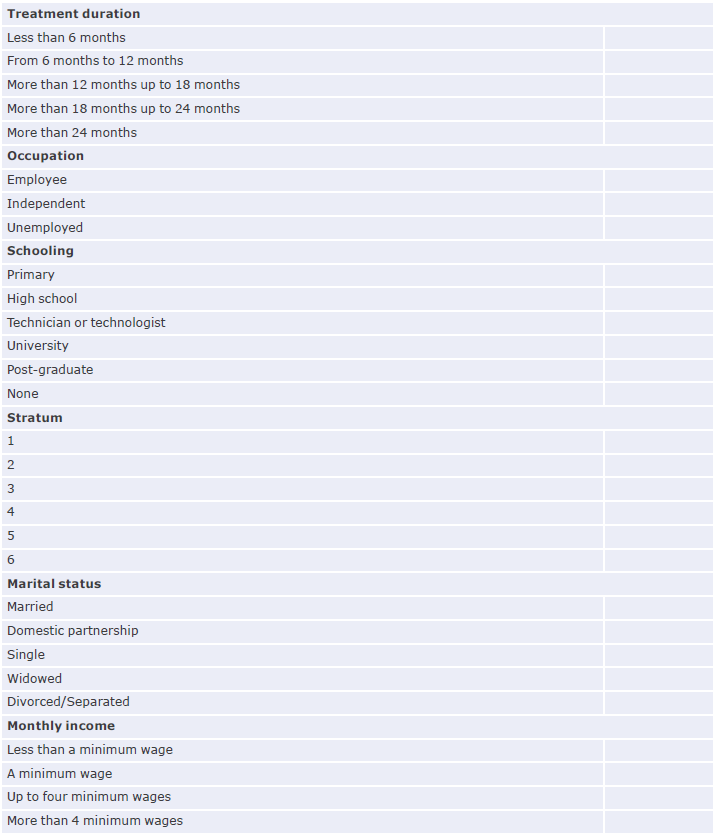

The original questionnaire has 37 questions rated using a Likert-type scale with five response options (very frequently, frequently, occasionally, rarely and never) and distributed in 5 factors: follow-up instructions (5 questions), patient engagement (9 questions), provider engagement (11 questions), importance given by the patient to treatment (8 questions), and health awareness (4 questions) (Annex 1).

Procedures

A pilot test with the original instrument (Annex 1) was carried out before the questionnaire was administered to 11 randomly selected patients who attended the orthodontic clinic at the institution's dental clinic. The test was administered by one of the authors and it allowed to establish that the average filing time was 7 minutes. Additionally, after the test, each participant was asked about perceived difficulties and asked to point out questions that caused those difficulties. In all cases, it was ensured that participants met the inclusion and exclusion criteria.

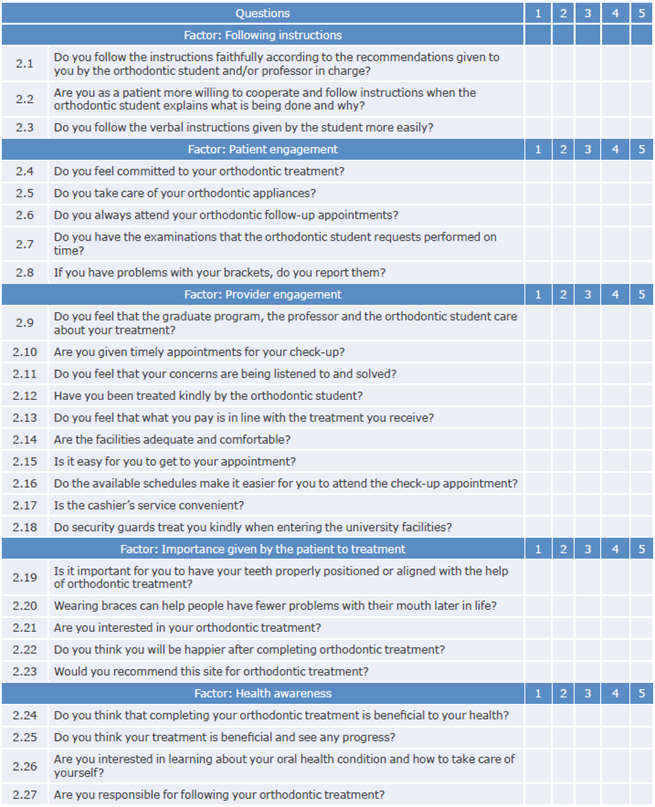

Based on the results of the pilot test, the research group carried out an analysis and a discussion and it was decided to remove 10 questions by consensus, thus obtaining the final 27-item questionnaire used in the present study (Annex 2). This instrument was administered in the waiting room of the university clinic to patients who attended orthodontic consultation in the dental clinic of the institution in two different periods: the second semester of 2018 and the first semester of 2019. The questionnaires were administered by four of the authors, who were trained for this purpose.

Statistical analysis

A scale dimensionality analysis was carried out using EFA in SPSS Statistics V22.0 and the Varimax normalization rotation method with Kaiser.26,27 The applicability of the factor analysis of the studied variables was previously verified through Bartlett's test of sphericity and the relationship of the correlation coefficients observed between the variables with the Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin (KMO) test.28 LISREL statistical software package was used for the CFA, which tested the level of adjustment of several models and selected the best fit model based on multiple indicators. The following indicators were used to estimate the models: Satorra-Bentler Chi-square (x2S-B), Satorra-Bentler Chi-square index divided by degrees of freedom (x2S-B/df), comparative fit index (CFI), relative fit index (RFI), non-normed fit index (NNFI), root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA), and standardized root mean square residual (SRMR).29

Results

Exploratory factor analysis

Prior to EFA, a reliability test was performed using Cronbach's alpha coefficient, which yielded a total value for the scale of 0.884, indicating good test quality.30

The sample selected for the dimensionality analysis of the instrument performed using EFA (n=202) is accepted as a fair sample for this procedure.20,21

The feasibility of the study was determined using the KMO test, obtaining a result of 0.806, and the Bartlett's test of sphericity,31 obtaining a result of x2=2197.535 with df=351 and p=0.000, values indicating that the variables are adjusted for factor analysis.

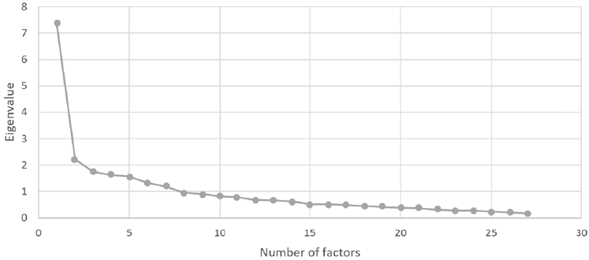

On the other hand, to determine whether previously constructed factors had a good significance in relation to all variables, visual analysis was used together with the Kaiser criterion,32 which indicates that only those factors whose eigenvalues are greater than unity (principal components) should be retained.1

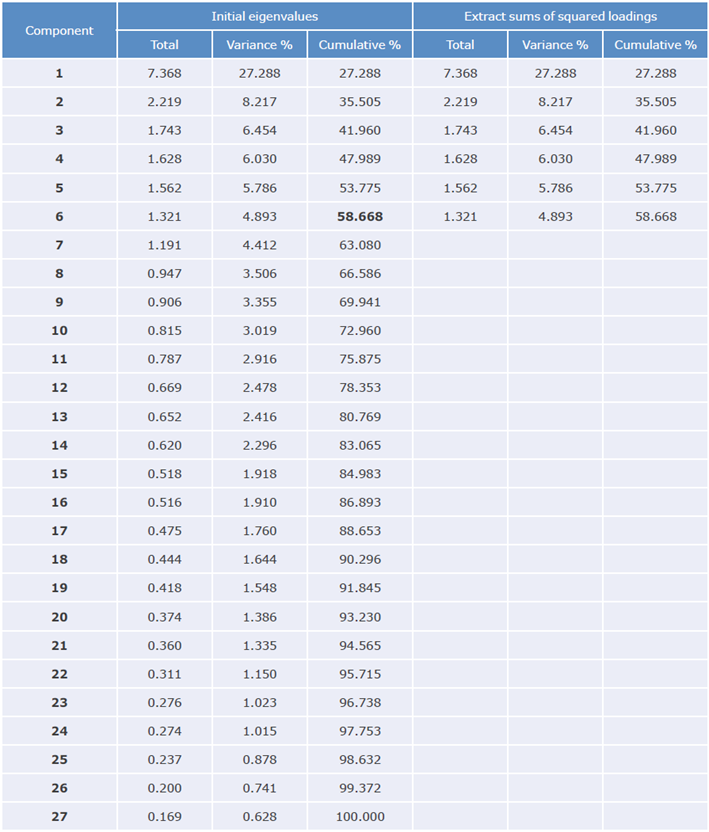

Figure 1 shows the possible factors and their dominance over others: the first has a significant difference from the other five and alone explains 27.288% of the variance, while the others together explain 29.380%. Although one more factor could be included with an eigenvalue >1 and a higher explained variance, the number of items per domain is reduced (less than three per factor) and the best fit is achieved with six factors.

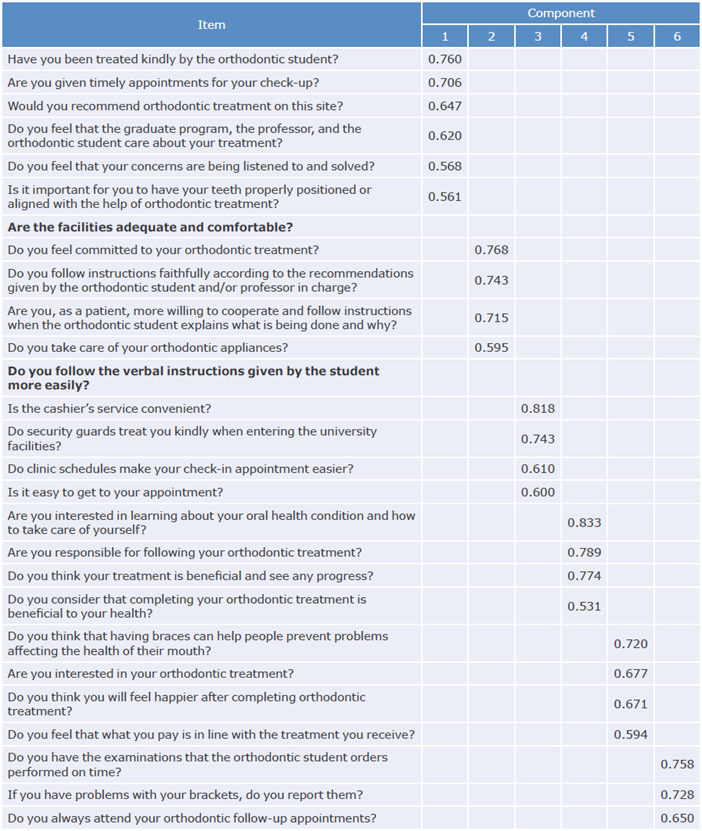

Of the six latent variables that contribute most to data variability, questions with loadings >0.50 were selected; they are presented in the table of rotated factor loadings (Table 1). Based on this perspective, two questions were removed from the instrument: "Are the facilities adequate and provide you with comfort?", with factor loading value of 0.415, and "Do you follow verbal instructions given by the orthodontic student more easily?", with an extraction value of 0.333, thus obtaining a final instrument with 25 questions distributed in 6 factors (Annex 3).

Table 1 Rotated component matrix with principal component analysis and Varimax rotation method with Kaiser normalization.

Source: Own elaboration.

Optimal adjustment was decided for 6 factors (Table 1) that differ from the 5 proposed in the original instrument, with a total explained variance of 58.668% (Table 2). Since the 6-factor fit differs from the initial instrument, an CFA was required to verify the correct adjustment of the instrument created in relation to the model established in the EFA.33

Table 2 Total variance explained for the factors in the exploratory factor analysis.

Source: Own elaboration.

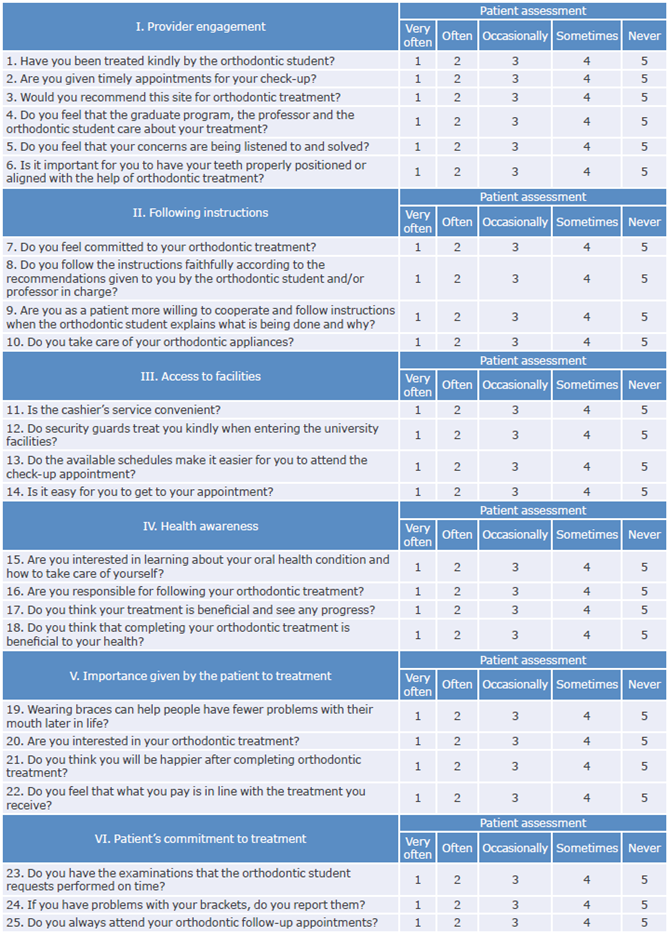

Thus, based on the results of the EFA, the present study proposed an instrument of 25 questions distributed in 6 factors to measure adherence to orthodontic treatment (Annex 3): provider involvement (6 questions), follow-up of instructions by the patient (4 questions), access to facilities (4 questions), patient awareness of health from an orthodontic perspective (4 questions), importance given by the patient to treatment (4 questions), and patient commitment to treatment (3 questions). In this way, the main intention of the EFA was fulfilled, which has to do with generating as few factors as possible to explain the greatest variability allowed in the data.

Confirmatory factor analysis

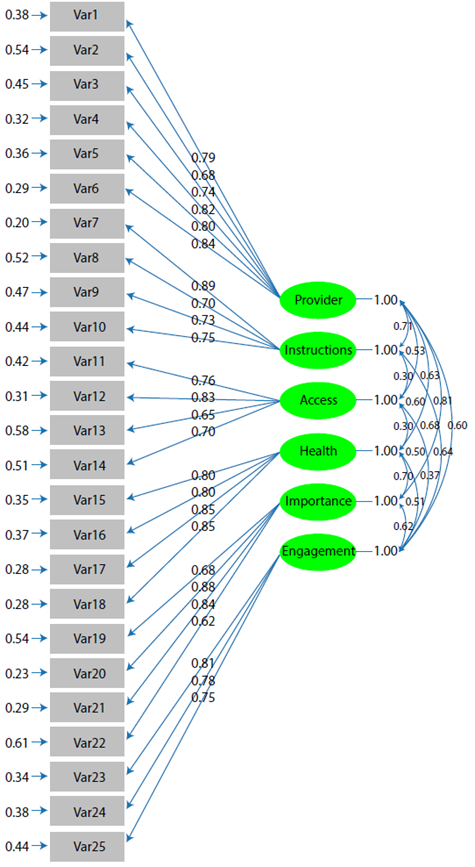

CFA was performed using the LISREL software and the diagonally weighted least squares method; the same six factors used for EFA analysis were used for CFA and the results are shown in Figure 2.

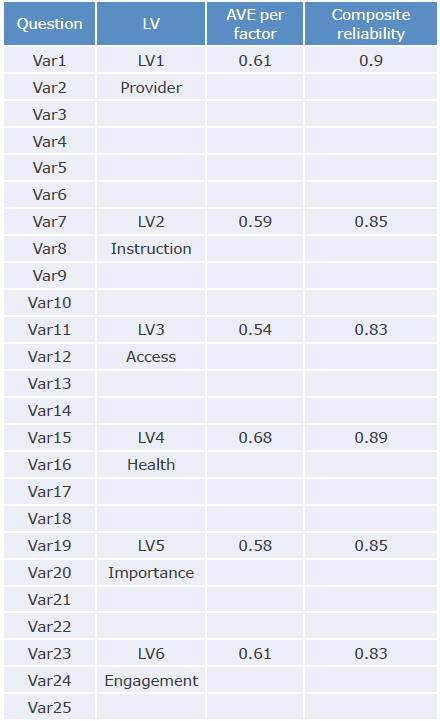

Using the values obtained in the loadings for the CFA model, the composite reliability analysis of the scale per factor was carried out, obtaining acceptable values (>83%) (Table 3). Furthermore, the selected model was analyzed to determine the convergent validity that proves that everything was related in the constructs.34 To verify this validity, the standardized factor loadings were determined (Figure 2) for all the latent variables >0.6 and the T values that were significant (>1.96), which allowed verifying that the obtained model has convergent validity.35

Table 3 Average variance extracted and composite reliability per factor in the confirmatory factor analysis model.

LV: latent variable; AVE: average variance extracted.

Source: Own elaboration.

Discriminant or divergent validity allows to estimate when a particular construct measures a different concept when compared with other constructs. In this sense, it is expected that the variance of the construct to be compared will be higher than the variance of the others included in the model,36 as found in the present study, where the values of the average variable extracted from each construct were greater than the square of the correlations of the others,37 indicating sufficient discriminant validity in the content of the instrument.

On the other hand, in the model fit obtained by CFA, the following adjustment values could be determined: x2SB=420.09 with df=260 and p<0.05; B/df=1.62; CFI=0.99; RFI=0.98; NNFI=0.99, RMSEA=0.039 (90%CI 0.032-0.046), and SRMR=0.057.

Discussion

Dimensional analysis using EFA and CFA makes it possible to adjust the factors of a given instrument in such a way that a good proportion of information can be extracted with an acceptable number of items and clear dimensions adjusted to important reliability values.

The literature shows a discussion about the correct definition of adherence to treatment because some concepts, that in most cases do not agree with each other, are used.11 The authors of this study argue that the concept goes beyond patient adherence to recommendations made by medical staff. In addition, it follows that this is not a one-dimensional concept in which the options are either met or not, but rather that this adherence is nuanced by a series of aspects that depend on several dimensions little explored when addressing it, as it is a complex construct that requires to be explained from different perspectives.

Based on these primary concepts, adherence to treatment is understood as an alliance that patients establish with the personnel who care for them and provide them with health services, which involves elements such as the relationship with the physical infrastructure, access to facilities, the behavior of the non-treating staff, among others.

In this sense, Martín-Alfonso11 states that adherence to treatment is related to a complex patient behavior involving their will and behavioral and relationship aspects, which determine their participation in the proposed process to achieve the expected results. These aspects have to do with acceptance of and compliance with the treatment planned by the health operator, as well as the instructions given by that health operator. Moreover, the active participation of patients to seek solutions that help them achieve the proposed goals and the evidence of the individual's will to comply with the instructions are also part of the elements that should be considered when talking about adherence to treatment.

All these aspects point to the multifactorial nature of adherence to treatment and demonstrate the need to address it through various combinations of factors in order to achieve significant results in terms of patient compliance.38

According to Lago-Danesi,39 adherence to treatment involves aspects related, on the one hand, to the care staff and the health system and, on the other, to the needs and socio-economic environment of the patient. Although these elements are a fundamental part of the professional-patient relationship, some authors do not take them into account when developing theories regarding adherence, which suggests that research, information and consensus are still lacking in this field.

There are multiple methods for measuring adherence;9 however, they need to be comprehensive, so that the resulting measurement is adequate. Consequently, it was proposed to create a complete instrument to measure adherence to orthodontic treatment in dental clinics of dentistry schools that treat a high number of patients. To achieve this, the authors relied on the factors that WHO associates with the concept12 and that involve aspects of the health system that are related to the health condition of each individual, the type of therapy, and the patients themselves.40

From this perspective, taking the original instrument of 37 questions and 5 factors as input (Annex 1) and after the EFA and the CFA, it was possible to reorganize the questions and obtain a validated instrument with 6 dimensions and 25 questions (Annex 3): provider engagement, follow-up instructions, access to facilities, patient awareness of health from an orthodontic perspective, importance given by the patient to the treatment, and patient commitment to the treatment. In addition, these factors were tested by means of a CFA and the results showed a model with six latent variables fitted to the data, which add aspects associated with the service provider to the definition of adherence, giving the users of the questionnaire greater confidence in its application.

Data fitting in the present study was adequate for the assessed model, as the CFI value was >0.92 (CFI=0.99) and the RMSEA value was <0.07 (RMSEA=0.039), as Taasoobshirazi & Wang indicate it should be.41

For Likert-type scales, the LISREL software provides the x2 related to the likelihood ratio (X2 S-B).42 It is a very good estimator when working with categorical variables or when dependent variables do not follow the normal distribution,43 and is calculated to evaluate the fit between the hypothesized statistical model and the set of observed variables. A X2 test with a statistically significant result (p<0.05) suggests that the model does not fit the data, as was the case with the one proposed in the present study; however, there is serious discussion regarding the statistic being sensitive to sample size and often rejecting the model, for which an alternative was proposed in which the value of x2 is divided by the degrees of freedom (X2/df).44 It is assumed that this reduces the constraint and the model can be better assessed globally. In this way, the data in the present study fit the model since the estimate of degrees of freedom is <0.3.45,46

According to Schreiber et al.,47 in general, a CFI should be >0.95 to consider that the model fits the data adequately. This index compares the X2 S-B of an independent model in which it is accepted that there is no relationship between the variables of the model with another model proposed by the researcher, and this comparison requires correction for the degrees of freedom in both models.48 In this study, CFI was 0.99, a value that indicates that an adequate fit of the data is met according to this perspective.

On the other hand, RMSEA is considered an approximation error and refers to the amount of variance not explained by the model per degree of freedom. As Mo-rata-Ramirez et al.43 point out, an RMSEA value <0.05 indicates that the model proposed by the researcher fits the data. However, according to Herrero,48 this value is more significant if the confidence interval (90% CI) is between 0 and 0.05. Thus, the RMSEA=0.039 together with CFI = 0.99 and CI90%=0.032-0.046 obtained in the present study indicate the good fit of the model.

Likewise, it should be noted that if there are accepted values for RMSEA and CIF in practice, then it can be accepted that the model has a good fit, and it is very unlikely that it is not fit for the data.48

Finally, SRMR is defined as the standardized difference between the observed correlations and an expected or predictive correlation and is considered an absolute measure of fit. This indicates that a value equal to zero corresponds to a perfect fit and a value less than 0.08 allows us to establish that the model fits correctly. 49 Thus, the value obtained for SRMR=0.057 in the present study indicates a congruent measurement between the data.

Conclusions

EFA and CFA made it possible to establish a valid instrument with a high level of reliability to measure adherence to orthodontic treatment in dental clinics of dentistry schools where a high number of patients are treated. Therefore, its use in similar institutions will allow to reliably determine the levels of adherence in these patients, and thus, when necessary, to develop and implement actions that encourage greater commitment of this population to orthodontic treatments to obtain better outcomes.