Introduction

At present, there is widespread confusion as to what the best food practices are, which is largely due to the amount of information available on the Internet offering the population an infinite number of discourses created not only by marketing interests,1-3 but also by certain sectors of the academia, civil society and social movements that attempt to develop better public policies to protect the human right to food.4,5

This conflicting interests scenario can be explained by reviewing the history of nutrition as a modern science, which dates back approximately 100 years, since it is attributed with both favorable and unfavorable aspects in the food and nutrition field. At the beginning of the 20th century, researchers in the area of biochemistry and medicine, with the primary objective of contributing to public health, were able to isolate specific food components (later called vitamins) related to the prevention of major population problems of the time, such as protein-energy malnutrition, beriberi, osteoporosis, pellagra, and scurvy.

Achieving these isolates allowed the generation of strategies such as the massive and mandatory fortification of the main food drivers containing vitamins. However, simultaneously and moving away from the primary interest of public health, the pharmaceutical and food industries have taken advantage of this opportunity to disseminate the technological modification of foods to create industrialized edible formulas for their economic benefit.6 As a result, the food industry began to become more high-tech, resorting in many cases to corporate policies that promote the industrialization, trade and marketing of ultra-processed food products (UFP) and multivitamin or nutrient-specific supplements that involved little or no natural food at all. The problem with this lies in the fact that, although this process is based on the claim of improving the food and nutritional security of the population, it has economic foundations.7,8

Of the many discourses on nutrition and food, two opposing perspectives stand out: "nutritionism" and "healthy, supportive, and sustainable food" (HSSF). Some researchers in the field of philosophy have associated the phenomenon of technological development in the food industry with the perspective of "nutritionism," in which food is reduced to the presence of nutrients and health to the absence of disease.9 This perspective has been the basis for much of the theory of modern nutritional and food sciences, including the development of food guidelines, public policies and social programs, or the conceptualization of nutrient recommendations or adequacy.10

Therefore, from the perspective of nutritionism, what is known as adequate or healthy nutrition has not only been insufficient to solve current food and nutrition problems, but also to address the multiple forms of malnutrition, especially in vulnerable and disadvantaged communities.11,12 On the contrary, this concept has been used by large corporations that have interfered in public health initiatives by camouflaging their commercial interests and creating strategies that have led to address all aspects of the food and nutrition issue based on unhealthy products.4,13-15

In contrast to nutritionism, some scientists have been conducting research that encompasses theoretical, scientific and political aspects of food, an activity that probably arises as a result of the socio-environmental crisis that is taking place around the world and the ongoing struggle of communities to achieve their own benefit. Such a struggle is rooted in the popular wisdom that emerges predominantly from the rural sector and indigenous communities in defense of the process of biocultural evolution associated with natural food, as well as in the recognition of the perspective of the HSSF and the human right to food. This is a conception that goes beyond isolated food, its nutrients and their adequacy, and is oriented to more holistic approaches, such as food patterns, that are influenced by practices that must be reconsidered based on different ideas related to food as a social fact.

Thus, the HSSF approach aims to improve the epidemiological, food and nutritional situation of populations from a broad perspective. To this end, the knowledge of various social actors is combined, so that an epistemological and multi-paradigmatic stance is adopted to redesign the food system to make it truly healthy, supportive and sustainable, while acknowledging the historical relationship of human beings with food, one that is in harmony with nature and not based on unhealthy, unfair, and unsustainable industrial formulations associated with corporate food regimes.16-20

In this sense, this article presents a reflection on these two perspectives (nutritionism and the HSSF), taking into account the historical panorama and the socio-political environment that characterize them, with the purpose of contributing to the recognition of a food paradigm that is in line with the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs)21 and the human right to food. In addition, this reflection aims to assess the progress that has been made in Colombia to ensure HSSF for the general population.22

Food from the nutritionism perspective

The nutritionism perspective was originally outlined in Australia by philosopher Gyorgy Scrinis as the dominant paradigm of modern nutritional science and dietary recommendations. It is characterized by a nutritionally reductionist approach to food that is limited to the interpretation of the role of nutrients in body health, resulting in a decontextualization, simplification, fragmentation, exaggeration, and determination of the role of nutrients.9

In 2007, the term nutritionism was reappropriated and popularized by Pollan,23 who argued that because science has an incomplete understanding of how food affects the human body, relying solely on information about nutrients has led people and policymakers to make multiple wrong decisions about nutrition issues.24 As a result, some entities that control much of the world food trade and are related to the World Health Organization (WHO), such as the Codex Alimentarius, conceive food as processed, semi-processed or raw substances intended for human consumption. They include beverages, chewing gum and any substance used in the manufacture, preparation or treatment of food, and exclude cosmetics, tobacco, or substances used only as medicines.25

According to the above definition, foods derived from plants or animals (fresh and natural) are comparable to industrial formulations (UFP); therefore, in legal and public policy scenarios related to food, it is possible to equate a piece of chewing gum and a piece of fruit in terms of the provision of basic elements to maintain biological systems. This promotes an ambiguous conceptualization of a term as basic as "food", which generates confusion in reference institutions and among food and nutrition decision-makers.

Such a picture suggests that citizens are immersed in a corporate food regime that does not emerge randomly and that operates on the basis of economicism and under the ethics and logic of the market. Moreover, this regime is characterized by the fragmentation and industrialization of food through global corporate models that break the link between people, food, nature and health, and that also ignores the social function of food culture and partially alienates the individual from his or her biocultural universe by treating food as a commodity and not as a common good, creating social instability and showing little concern for the environment.5

In addition, there is a global homogenization of food that is partly explained by the reduction of the concept of food to a system of nutrient transfer through industrialized food products, as well as the invisibility of the relevance of biocultural and culinary evolutionary development achieved by mankind for thousands of years using natural and fresh foods under the ethical principle of the common good. Thus, the current challenge is to rescue the holistic vision that ancestral peoples had of food, specifically the concepts of planetary and social boundaries (which have been rapidly developed in the last decade by various organizations and can be summarized in the MDGs)21 and to reinforce the importance of conceiving food as a global issue, since this is the only way to be able to speak of HSSF.

Food from an HSSF perspective

The modern population's lack of knowledge about the natural origin of food and the cultural richness of the culinary universe highlights the importance of promoting greater integration between food sciences within nutritionism, which tend to take a materialistic approach, and human and social sciences. In this regard, Fischler26 established that food can be considered as a social, cultural and political fact that is intersected by direct and indirect determinants related to health, nutrition, culture (education and religious beliefs), economy, among others.

Accordingly, in the HSSF perspective, food is conceived beyond the purely biological processes associated with nutritionism (nutrients and disease), so a healthy, supportive and sustainable food approach is envisioned. On the one hand, this favors the adoption of food patterns based on natural or minimally processed food preparations acquired through solidary socio-environmental models that are in tune with the protection of nature and with the culinary universe that emerges in each context. On the other hand, this avoids food patterns associated with the corporate food regime, which is characterized by large-scale production and marketing of UFPs associated with the presence of different forms of malnutrition and chronic diseases (CD) such as obesity, diabetes, hypertension, cancer, and cardiovascular diseases (diseases closely related to the global burden of disease), as well as with forms of marketing that are usually unfair and environmentally unsustainable.18,27

From the HSSF perspective, foods obtained from nature and with which mankind has evolved biologically, socially and culturally for thousands of years are recognized as foods which, through culinary methods, have been transformed into preparations that provide health, social stability, harmony with the environment, and cultural identity. Likewise, based on this vision, multiple methods have been designed throughout history for the preservation and processing of these foods to avoid shortages in times when climate or seasonal issues do not allow their procurement.24

Therefore, in HSSF, the problem is not food processing, but ultra-processing because, with the latter method, food is subjected to highly invasive industrial processes that result in an edible product with little or none of the original food content. Moreover, ultra-processed foods usually have a high content of fat, salt, sugar and cosmetic chemical additives, preservatives, and texture modifiers that are associated with unhealthy, unfair, and unsustainable diets that push out the traditional culinary culture and fails to take care of the environment.28

In this sense, the HSSF perspective advocates the collective defense of the human right to food from a multidisciplinary approach, recognizing the essential nature of food for human beings since the beginning of time and acknowledging the juxtaposition of traditional knowledge about food. Consequently, it is essential to recognize food as a vital biological function as well as an essential social function, since it has a structuring role in human social organization and impacts the natural environment that surrounds them.5

Additionally, according to the HSSF perspective, the term healthy not only refers to the absence of disease; in fact, this is a broader concept related to physical, mental and social well-being that allows individuals, families and communities to enjoy a dignified life.29 Hence, the concept of healthy is associated with anything that gives people health, which, in this case, is food and its nutritional components, as well as the ways of eating that allow them to enjoy their lives in the best possible way. Thus, HSSF attempts to grasp dietary patterns and the culinary universe, not as a repetitive consumption of nutrients or individual foods to avoid getting sick, but as individual and collective actions conditioned by social, political, economic, environmental, commercial, and cultural determinants that act as modulators of food and consumption among human collectives.

Other components that should be consolidated under the perspective of HSSF are solidarity and sustainability. Academic and political proposals at this point aim to address the socio-environmental dimension of food since there is an inevitable link between production forms, distribution, access and consumption of food, and social stability, environmental protection and human health.

Specifically, HSSF analyzes the dynamics of the traditional and ancestral food system with which we have co-evolved in a healthy, supportive and sustainable manner. It also characterizes how this traditional ancestral food system comes into conflict with global corporate food systems as they contribute to the depletion of natural resources, such as land and water, and to social deterioration due to the increase in food and nutritional inequalities and inequities, not only among consumers, but also among producers.18,30

At the same time, the solidarity component of HSSF proposes to recognize the importance of the human right to food and good living, which strengthens the food culture of populations and territories influenced by food exchange habits based on knowledge, attitudes of solidarity and historically differentiated food practices. It also aims to take into account the problems arising from practices that violate the human right to food and are related to the production and marketing of food at local, national and international levels,1-3,26 for which the role of phenomena such as globalization, industrialization and homogenization of food patterns linked to the increase in the indiscriminate consumption of UFPs and the establishment of unhealthy, unsupportive and unsustainable corporate diets that increase the occurrence of CD should be understood.28

With respect to sustainability, new theoretical currents are being promoted, such as MDGs,21 planetary boundaries, and planetary diets.31 From these, work is being done to build a safe space for humanity in which the priorities of the planet and its inhabitants are to reduce poverty rates, eradicate human deprivation, and ensure the well-being of human beings and the environment. Efforts to achieve these goals come from different sectors. For example, after the MDGs were established21 at the Rio+20 Earth Summit in 2012, a theoretical framework that combines planetary and social boundaries was discussed with the intention of creating a safe and fair space in which humanity can develop32 and, recently, a group of experts made a proposal that refers to planetary health diet and aims to establish healthy diets based on sustainable food systems.33

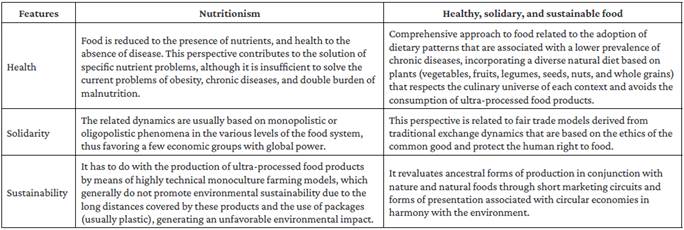

Accordingly, it is necessary to recognize the characteristics of nutritionism and, consequently, of modern food practices that have led us to adopt a food configuration that is generally unhealthy, unsupportive, and unsustainable. For this reason, there is a need to return to traditional or ancestral forms of interaction with food and/or to adapt to new forms of interaction as proposed by HSSF. Table 1 summarizes the differences between these perspectives on food based on health, solidarity, and food sustainability.

Towards HSSF in Colombia

Since the 1990s, a corporate food regime has emerged in Colombia with the following characteristics:18,34

Regulatory frameworks are established in accordance with the capitalist industrial agrifood system.

Seeds are privatized, and their conservation and free circulation is restricted.

The intensive use of chemical inputs and fertilizers, as well as the massive production, importation, and sale of food products is encouraged.

Land grabbing by national and foreign corporations is promoted in large regions of the country, such as the non-flood areas near the Meta River in the Eastern Plains (known in Spanish as altillanuras).

Agro-industrial processes and the extension of monocultures are favored.

The expansion and increase of food distribution chains in large supermarket formats is stimulated.

The proliferation of UFP sales (of national and international origin) and the opening of new branches of fast-food chains in different food environments is increased.

The increase in the obesity, CD, chronic malnutrition, and micronutrient deficiency levels is facilitated.

The establishment of a business bloc in the agricultural and food sector is allowed.

This corporate food regime acquired strength in the country at the beginning of the 21st century when, as noted by Machado,35 the process of deinstitutionalization of the public sector regarding the rural sphere was reinforced and consolidated by Law 790 of 2002,36 which also conferred extraordinary powers on the President of the Republic. This led to the enactment of Decree 1300 of 2003,37 which ordered the dissolution of the Colombian Institute of Agrarian Reform, the National Institute for Land Readjustment, the Co-financing Fund for Rural Investment, and the National Institute for Fishing and Aquaculture and created the Colombian Institute of Rural Development. This change resulted in the precariousness of the rural sector due to the drastic reduction of the sown area, which had a strong impact on peasant economies. Consequently, food imports increased (especially of UFPs),38 and food security, sovereignty and quality in the country were compromised, which in turn increased the many forms of malnutrition, especially among the most vulnerable populations.14,15,39

On the other hand, the civil society, a political sector, and a part of the academia that are committed to the defense of the human right to food have encouraged the acknowledgement of movements to defend food sovereignty in different local contexts, which allows working for the protection of the traditional, ancestral, healthy, solidarity-based and sustainable food system in the various scenarios of public policy discussion in the country,40-43 as well as counteracting the strategies implemented by the corporate food regime set up in Colombia.4

The armed conflict experienced in Colombia for decades at different political levels is also an equally important factor that has influenced food policies in the country, since peasants have been the most affected by the clashes over land. However, there is a glimmer of hope with the peace agreement signed in Havana because a comprehensive reform, as stated in the agrarian agreement, will undoubtedly have a positive impact on the country's food and nutritional security.35

All these signals and efforts have opened spaces in which progress in public policies on food has been made, with a strong role of academia, civil society and governmental entities, as is the case of Law 2120 of 202144 and Ordinance No. 5: Twelve-year Plan for Food and Nutritional Security of Antioquia 2020-2031.45 This political progress represents a commitment to work by different sectors in order to include the programs and goals proposed in Ordinance No. 5 in the various development plans for the municipalities of Antioquia and to achieve a food system that is conducive to achieving HSSF depending on the differing realities of the department.

In accordance with the above, in the near future, work should continue to i) facilitate spaces for debate in academic circles, civil society, the community in general and political scenarios regarding the convenience of changing the current corporate food regime associated with nutritionism to a healthy, supportive, and sustainable food system; ii) recognize the political strategies that favor the establishment of the corporate food regime in the country; iii) highlight, promote, and replicate successful experiences that promote HSSF from the popular bases of traditional ancestral culture; and iv) establish public policies aimed at implementing a food system that is truly designed to promote HSSF among citizens in different decision-making scenarios (municipalities, governor's offices, presidency, and congress).

Conclusions

The current food perspective of nutritionism associated with the corporate food regime requires a paradigm shift towards the HSSF perspective. In Colombia, the efforts made to change the corporatist food regime for a healthy, supportive and sustainable food system need to be strengthened by different academic, civil society, community, and political actors in order to defend the human right to food.