Introduction

Multiple analyses of variables related to quality of health care have established that the approach to the relationships between the people involved in the provision of health care services (health care professionals and workers, patients, caregivers and administrators) is paramount.1 Such analyses have also shown that although the implementation of changes and the modernization of health care services have been aimed at improving safety, effectiveness and efficiency,2 several of said changes have resulted in the fragmentation, depersonalization and dehumanization of care.3

Thus, it is common for health care workers to suffer from stress, burnout syndrome and compassion fatigue because they have to perform their duties in a dehumanized environment.4 The business logic implemented in health care services has a strong influence on health care workers, affecting the variables of interaction between them and patients,5 as well as the method used for their appraisal, which is centered on productivity indicators. Moreover, this logic has brought about a detriment in the salaries of this population and in the means of recruitment, which is why the current status of these two aspects is not consistent with the high level of responsibility and time and money invested, nor with the sacrifices that these professionals must make during their training process.6

This situation has led to mistreatment of students, which has become naturalized throughout their academic training and permeates their professional and work practice.7 The above is related to the fact that the academy has given more emphasis to scientific and technical fundamentals when training human talent, and therefore, to some extent, has neglected humanistic training.8

Nevertheless, many practitioners and scholars have made efforts to adopt a more humanistic approach to health care, although they have not always had the support of decision-makers at the highest levels of management or government. In this sense, in 1969, Balint9 proposed that health care should be based on the patient and not on the disease, which implies that professionals should demonstrate compassion and empathy for the patient, their values, needs and preferences, and also involve them in the decision-making process. This concept has gradually transformed, and its scope has broadened to encompass not only professionals and patients, but also caregivers, administrators, and policy makers. In this way, the concept of humanization in the provision of health care services emerged.10

Humanization in health care, then, can be defined from different perspectives and involves different actors. Accordingly, some authors, such as Todres et al.11 approach humanization from the perspective of care associated with health care, while others, such as Pérez-Fuentes et al.12 approach it from a multifactorial model that explains the personal competencies and skills that ensure dignity and respect for the human being. It should be noted that, regardless of the approach or model used to define humanization in health care, there is a common factor: humanizing health care services implies taking a comprehensive view of the human being and of the entire care process, so that the responsibility of each of the actors involved is recognized right from the beginning.13

Considering the above, the aim of this article was to describe the bases and general aspects of the design and implementation process of the Comprehensive model for the humanization of health care of the Faculty of Medicine at the Universidad Nacional de Colombia, which began to be developed in 2016, and has also been implemented at the Hospital Universitario Nacional (HUN) and incorporates humanization in the training of students in the health area, health care services, and the quality of life of health care workers. Consequently, this model contributes to produce the changes required for the humanization process of health care, from the training of health professionals to the care of patients.

Humanization in Colombia

Rodríguez14 suggests an interesting explanation of how aspects associated with humanization have developed in Colombia. For this author, it is possible to identify at least three aspects when approaching humanization in health care services: the first has to do with the work of some religious communities dedicated to providing services associated with health care and especially related to aspects such as structures of belonging, dialogue, spiritual and emotional support, active listening, and reassurance; the second is guided by the vindication of the rights, autonomy and respect for the will and integrity of patients; and the third is an intermediate trend that regards health care humanization as a quality challenge for institutions, focusing not only on the humanization of user care, but also on addressing the problems of the workers.

In Colombia, the Ministry of Health and Social Protection has incorporated humanization into its policies and guidelines to improve the quality of health care and has established that humanization implies considering health as a matter of well-being, understanding, and respect for values, traditions and culture, in which changes in organizational culture have an impact.15 In this context, based on the guidelines of Law 100 of 1993,16 the National Plan for Quality Improvement in Health Care (PNMCS by its acronym in Spanish)17 was established. It seeks to propose applied and visible solutions that respond to the need to improve the quality of care and allow institutions to address this need and generate institutional policies, programs and strategies that favor human-ization with the support of official bodies,18 which ultimately makes it possible to put the concept of humanization into practice.

Humanization at the Universidad Nacional de Colombia

The Universidad Nacional de Colombia has developed pioneering works on humaniza-tion. One of these is the book authored by Roldán-Valencia, entitled Medicina Humanizada and published in 1991,19 which gathered various reflections and proposals from experts on this subject, and also made it possible to make a special call for humanization in the training of health sciences students.

Then, in 1997, the publication of the book Hacia una medicina más humana by Mendoza-Vega et al.20 marked another milestone in the analysis of health humanization in the Latin American context, since its most important contributions include the approach to different issues of health care humanization with a life-course perspective, and the inclusion of other professions (such as nursing) and the perspective of patients' rights in the analysis of humanization.

Subsequently, in 2007, with respect to the training of health professionals, the Pedagogical Support Group of the University's Faculty of Medicine formulated reflections on the conceptualization of students and professors as actors of the humanization process in the provision of health care services with their own characteristics, skills and aptitudes, as well as those related to the patient.21 However, the Humanizing Health Care Research Group questioned why, after these proposals had been made,21 it was not until 2010 that the topic was explicitly taken up again by the faculty through the hiring of an expert in humanization.

The Humanizing Health Care Research Group of the Faculty of Medicine, whose model is described in this article, was formed in 2016, gathers the advances achieved by the faculty in this area, and articulates its activities around the mission axes of the university: teaching, research, and university social projection.

At the beginning, the group analyzed the fragmented way in which humanization in health care was being addressed in the country and established that it was affecting the sustainability and viability of the different proposals and projects on the subject, and consequently their results in the medium and long term. From this analysis, the research group also reached the following conclusions: 1) there were no courses in the curricula of the undergraduate health science programs that provided opportunities for training in humanization issues; 2) it was necessary to analyze the causes of abusive behaviors by health care professionals and their origins in the training process; 3) the abusive behaviors by health care professionals had been normalized during the training process and were influenced by their working conditions; and 4) it was necessary to understand the biopsychosocial foundations of humanization by approaching it as a study phenomenon and not as the implementation of isolated actions aimed at manifestations rather than causes.

Similarly, in their analysis, the Humanizing Health Care Research Group found that the predominant vision of humanization directed exclusively at patients reduces its scope and that by extending it to professionals, workers, families, caregivers, administrators and managers, the environment changes and a systemic vision of the problem is assumed. Also, through this analysis, it was concluded that most undergraduate programs did not consider health care professionals and workers in terms of the appropriate conditions for the performance of their work or their quality of life, and that humanization actions and projects stem from the administrators of health care institutions or patient movements. In this respect, the Humanizing Health Care Research Group established that universities are not implementers of comprehensive humanization policies or activities and, based on this, it developed the comprehensive model for the humanization of health care presented here.

Comprehensive model for the humanization of health care developed by the Humanizing Health Care Research Group of the Faculty of Medicine at the Universidad Nacional de Colombia

The conceptual bases of the Comprehensive model for the humanization of health care of the Faculty of Medicine of the Universidad Nacional de Colombia are based on the promotion of empathy and the theory of mind and are related to intersubjectivity and communication.22 Hence, the model is aimed at the university's missions, namely, teaching, research and university social projection, addressing humanization in these components with a holistic view. This model is also being implemented at the HUN, given the interaction between both institutions.

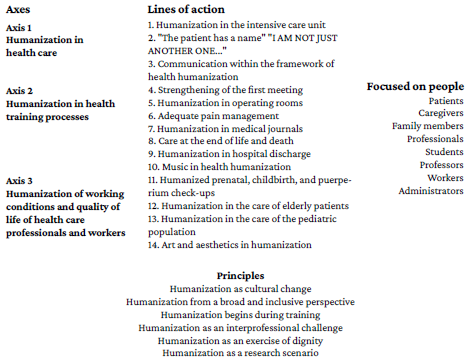

The novelty of this model is the inclusion of the interactions between the people involved in it, focusing on relational, organizational and structural changes in the health system. For its creation, the activities and strategies previously implemented, the theoretical bases on the evolution of humanization and the actors involved in the training and health care process were all analyzed. Figure 1 outlines the axes and principles of this model.

Source: Own elaboration.

Figure 1 Comprehensive model for the humanization of health care of the Faculty of Medicine at the Universidad Nacional de Colombia.

The model presented in Figure 1 is based on an understanding of the following principles:

Humanization as a cultural change: In order to generate the expected behavioral changes, a profound change is required to establish a new culture to guide the actions of the system's stakeholders.

Humanization from a broad and inclusive perspective: This model includes all levels of care and all actors in the system. With this multilevel vision, always focused on the person, the patient is the main axis and is surrounded by an environment that involves their family and caregivers, who must also be the object of humanization actions. In turn, health care professionals and workers are exposed to an environment with a high psychosocial risk that has a decisive influence on professional performance,23 so different studies have analyzed the effectiveness of humanization and care actions in reducing adverse conditions.24,25

Humanization begins with the training of future health care professionals: It is fundamental to include courses and cross-curricular contents on humanism and humanitarianism in the curricula of the different health programs, which should be available since the first academic terms. The reason for this is that by training students with a broad understanding of the nature of care and the importance of empathy, compassion and communication, it is possible to generate awareness in which situations of abuse in different scenarios are identified clearly and early on, in addition to providing professionals with the tools to respond in an assertive, proactive, and resolute manner in any situation.26

Humanization as an interprofessional challenge: This perspective encompasses the various professions and disciplines involved in health care and allows for the exchange of knowledge and horizontality in relationships through understanding and recognition of the other.

Humanization as a dignity exercise: Humanization must be based on the acknowledgement and exercise of the fundamental rights of all actors in the health system. In this context, the model considers that dignity is an articulating concept that should permeate each and every process (from health education to the practice of the professions); furthermore, understanding rights implies claiming the need to work for a dignified health system in which the limits of the economic model imposed on the fundamental right to health are addressed. This understanding of health, beyond the business idea, is the cornerstone of the required cultural and behavioral change, so understanding health as a fundamental right at all levels is also part of the humanization of health care. In this sense, it is necessary to raise awareness during the training process of health care professionals by promoting the recognition and enforcement of rights.

Humanization as a research scenario: Considering that humanization is a complex and multifactorial phenomenon, it is necessary to generate evidence to implement the required changes. For example, studying working conditions and their impact on physical and mental health in phenomena such as burnout or other mental disorders contributes to raising awareness among professionals so that they can demand better working conditions in an informed and appropriate manner, encouraging decision-makers to modify them and thus generate changes in public policy.

The model axes

The Comprehensive model for the humanization of health care of the Faculty of Medicine at the Universidad Nacional de Colombia is based on three axes, which are described below.

Humanization in health care

In this axis, efforts are mainly directed towards the patient, but there is also a strong emphasis on recognizing the role of family members and caregivers as an active part of the health care process to ensure that they are also included and taken into consideration as subjects to be approached within the framework of the humanization objectives.

Humanization in health training processes

This axis emphasizes two components, one related to the inclusion (from the first terms of undergraduate studies) of courses with basic concepts of humanization in the curriculum, and the other that seeks to ensure that the training spaces are permeated by positive behaviors. This implies the formulation of education policies and the development of actions to guarantee that training scenarios are free of abuse, harassment or bullying and that spaces for activities other than those established as mandatory are respected and guaranteed. This is articulated with a comprehensive education that includes recreational, artistic, and sports activities.

Likewise, this axis considers that the Comprehensive model for the humanization of health care of the Faculty of Medicine at the Universidad Nacional de Colombia should include the promotion of decent conditions for training, such as respect for adequate sleep schedules, and preventive actions against conditions such as burnout or the consumption of stimulating substances. Within this framework, it is necessary to monitor and accompany the human development of students, for which the tutorials offered by the university's Student Support System can be used.

Humanization of working conditions and quality of life of health care professionals and workers

The goal of this axis is to include health care professionals and workers as active participants in care processes and, therefore, as subjects of rights and the object of humanization programs and actions. Thus, this perspective contemplates the needs and rights involved in guaranteeing and maintaining decent conditions for the performance of their work.

The quality of life of health care professionals and workers is closely linked to the care provided to patients and caregivers; therefore, in order to guarantee humanized care, it is necessary to ensure the conditions of professional practice.

It is clear that the only way to establish the culture of humanization in a lasting and long-term manner is to work simultaneously on the three axes mentioned above, thus covering all the processes involved in them in a cross-cutting manner. In conclusion, it was found that the sustainability, progress and future of initiatives for the humanization of health care require this type of systemic and comprehensive approach.

Lines of action

The three axes of the Comprehensive model for the humanization of health care of the Faculty of Medicine at the Universidad Nacional de Colombia mentioned above are developed based on the following lines of action:

Humanization in the intensive care unit

"The patient has a name" "I AM NOT JUST ANOTHER ONE..."

Communication within the framework of health humanization

Strengthening of the first meeting

Humanization in operating rooms

Adequate pain management

Humanization in medical journals

Care at the end of life and death

Humanization in hospital discharge

Music in health humanization

Humanized prenatal, childbirth, and puerperium check-ups

Humanization in the care of elderly patients

Humanization in the care of the pediatric population

Art and aesthetics in humanization

Each line of action develops specific strategies aimed at improving humanization conditions, thus integrating the different people involved in the training and/or health care process.

Means to achieve humanization in health care

Artistic and sports activities are means to implement the cultural change inherent and necessary in the humanization training and awareness processes. These two means, together with humanistic training, make up a triad for humanization in health.

Music, which has been widely studied as a therapeutic tool, overcomes linguistic, physical, mental, and cognitive barriers to understanding others.27 For this reason, it has been used in different places as the main tool to promote humanization in hospital contexts. Additionally, its therapeutic effects in health care settings have been documented in multiple studies on palliative care28 radiotherapy,29 chemotherapy,30,31 pediatrics,32 invasive medical procedures,33 pain management,34 anxiety,35 quality of life improvement,36 etc.

In the same way, sports are an excellent way to deal with stress, emotions and free time for students and health care workers, as they play a fundamental role in the processes of integration and socialization. They are also an effective way to exemplify values and skills such as leadership, teamwork, assertive communication, and frustration tolerance.37

Consequently, participation in music and sports activities represents an opportunity for social exchange and the generation of connections, from the training stage to the professional practice.

Main achievements

Based on the 3 axes and the 14 lines of action of the Comprehensive model for the humanization of health care of the Faculty of Medicine at the Universidad Nacional de Colombia, different programs, events and activities have been developed, both at the university and at the HUN, which have strengthened the research group in charge and have made it possible to include the model within the policies of the Management Plan of the Dean's Office of the Faculty of Medicine as one of the 13 working axes of work.

The " Humanization in Health Care" course

Since 2016, when the Comprehensive model for the humanization of health care of the Faculty of Medicine of the Universidad Nacional de Colombia began to be developed, the course Humanization in Health Care has been offered uninterruptedly every term, even during the pandemic, with a total of 130 places for students of 9 health programs belonging to 5 faculties of the university: Medicine, Dentistry, Nursing, Human Sciences, and Sciences.

This course has an hourly intensity of 3 hours per week and a duration of 16 weeks. The methodology used for teaching it is participatory, which favors teamwork, leadership and self-management skills, and also promotes the development of additional projects on topics of interest in the area and presentations by experts. The students of this course also organize activities such as concerts and humanization cinema clubs for the whole community. In the latter initiative, a film related to one of the topics of the course is selected, a theoretical reflection is proposed, and a discussion is held between students and professors.

In addition to this course, we have been working on the inclusion of other contents related to humanism and humanitarianism in the curricula of the Faculty of Medicine's programs. Such contents include respect for the patient's point of view and consideration of their opinions when making decisions regarding their health, psychological care, acknowledgement of individuality in a person-centered model, the importance of family members and caregivers, the fundamental role of communication in health, the relevance of confidentiality and confidence, and the promotion of attributes and values such as kindness, compassion, and empathy.38

It should be mentioned that due to the confinement measures derived from the COVID-19 pandemic, the Humanization in Health Care course was adapted to the e-learning modality, keeping its excellent reception and appreciation on the part of the students.

Humanization in Health Research Incubator

The Humanization in Health Research Incubator was created in 2018 as a platform for students who had taken the Humanization in Health Care course to give them opportunity to deepen their knowledge of the contents by implementing a project developed within the framework of the problem-based learning strategy that included topics chosen by the students themselves.

Humanization symposiums

With the aim of disseminating and sharing activities with professionals and institutions, the Humanizing Health Care Research Group of the Faculty of Medicine, with the support of the faculty, developed the first Symposium on Humanization in Health in 2018. A second edition of this event was held in 2021 with the participation of leading Ibero-American experts on the subject, which led to the creation of the Network of Institutions for Humanization in order to share experiences and lessons learned with other institutions in the Colombian context.

Humanizing Health Care Research Group

The Humanizing Health Care Research Group has conducted several research projects, whose results have been successfully published.39,4° Moreover, there are also results that, despite not being published, have generated opportunities to explore issues related to humanization in specific scenarios.

Humanization in health care services

The HUN has been working on the implementation of humanization strategies in the 14 lines of action articulated in the model described here, which has allowed for the inclusion of humanization in the HUN's mission and establishing it as an institutional policy.

Also, the Humanizing Health Care Research Group has undertaken different initiatives to promote humanization not only in the faculty, but also in the entire university. Among these initiatives is the signing of the Pact for Good Treatment, and the development of activities such as the "Health Marathon", "I am not just one more" (delivery of pins with the name to each of the secretaries of the faculty), among others. Similarly, these campaigns have been directed to raise awareness and improve the relationship between the different members of the faculty and the university.

Finally, it must be stressed that one of the most important challenges of the Health Humanizing Health Care Research Group is to permeate the curricula of all health programs, consolidating cultural change and expanding the scope of training actions to all students to make the contents of humanism and humanization mandatory for all health faculties of the university. Likewise, the HUN expects to consolidate the lines of action, strengthen the research processes, and expand the scope to other universities.

Conclusions

Over the six years of development of the Comprehensive model for the humanization of health care of the Faculty of Medicine at the Universidad Nacional de Colombia, there has been progress that has consolidated its foundations, thus allowing its application to integrate and develop humanization in different scenarios. The programs and actions developed by the Humanizing Health Care Research Group have influenced the strategic policy of the Faculty of Medicine at the Universidad Nacional de Colombia and the HUN, including humanization explicitly in the health training policy of both institutions. In addition, this articulated work between academia and the hospital favors the follow-up and quality of the strategies developed.

In this sense, working simultaneously in the three proposed axes, including strategies at different levels with a clear interprofessional view, has been key to ensure that the activities and programs developed within the framework of the Comprehensive model for the humanization of health care of the Faculty of Medicine at the Universidad Nacional de Colombia are viable and productive. Therefore, it is expected to continue working along these lines in the medium and long term, in order to maintain the results and strengthen research in this very necessary and relevant subject. Our aim is also to strengthen the implementation of strategies to continue validating this model as the basis for the group's work proposal in its teaching, research and extension components. It is also expected to compare the aforementioned results with proposals made in other institutions around the world.