Introduction

Quite recently, the debate on moral responsibility started suffering from a proliferation of technical distinctions. Subtle differences are made between responsibility, attributability, answerability, accountability, and what not. Of course, it is a central task on a philosopher's job list to make distinctions and to put them to use in order to elucidate matters. But the deployment of a heavy technical apparatus might also be a symptom of an unfruitful scholasticism and a stagnating research program.

In this paper, therefore, I go back to square one: the very concept of moral responsibility. This backtracking implies that I will not enter the extensive and complex debate on the conditions of application for the concept of moral responsibility. I proceed as follows. Two conceptions of moral responsibility are first identified (section I). The Strawsonian and ledger conception of moral responsibility are then detailed (sections II and III). Next, I contrast these conceptions with one another (section IV). Finally, I will ask which of the two conceptions is the right one (section V). Although my discussion will end inconclusively (section VI), I intend this paper to contribute to getting clearer about the very concept of moral responsibility.1

I. Two Conceptions of Responsibility

What exactly are we doing when we attribute responsibility? Let "responsibility" stand for moral, retrospective, personal responsibility for actions. There is no unitary concept of responsibility. Two conceptions of responsibility are current in the contemporary literature: the Strawsonian and the ledger conception of the nature of responsibility.2 In the literature, the former is the majority view, the latter the minority one; at least, the Strawsonian is more discussed than the ledger view.

Both views give an analysis of (the concept of) responsibility. Such an analysis (or definition) formulates the elements wherein responsibility consists. The Strawsonian and the ledger conception differ sharply in their constitutive view on responsibility. On the Strawsonian view, the appropriateness of the reactive attitudes -in particular, resentment and moral indignation- grounds responsibility:

(S) Subject S is responsible for action A, if and only if, and because, it is (or would be) appropriate to adopt some reactive attitude toward S in respect of A.

On the ledger view, S's responsibility does not at all consist in such an appropriateness but in something altogether different; it is grounded in A's being part of S's moral record-or, metaphorically speaking, in entries in "the ledger of life":

(L) Subject S is responsible for action A, if and only if, and because, A is a part of S's moral record.

It is important to note that both conceptions are compatible with the following claim:

(1) Subject S is responsible for action A, if and only if, it is (or would be) appropriate to adopt some reactive attitude toward S in respect of A.

Notice that (1) does not give an analysis of responsibility. (1) does not express a grounding of responsibility but only a general biconditional between responsibility and reactive attitudes. By using the "if and only if, and because" formulation, (S) and (L), in contrast, express grounding relationships.

Before explaining both views further, I comment on the structure between (S), (L) and (1). This structure will become important in section V. Compared to the relations of correlation and causation, (1) is like a correlation, whereas (S) and (L) are like asymmetric causal relations. The weaker equivalence relation ("if and only if") correlates responsibility and reactive attitudes; the stronger grounding relation ("if and only if, and because") makes responsibility asymmetrically dependent upon either reactive attitudes or the moral record. In light of this structure, one can observe that (L) also allows for a systematic correlation between reactive attitudes and the moral record, although it is only the latter that grounds responsibility. So, both (L) and (S) are compatible with (1).

To clarify this structure a bit more, consider the following analogy. Take virtue ethics and (act) utilitarianism (Johansson and Svensson 2018). Both moral theories are compatible with this equivalence:

(1') An action is right, if and only if, it is what a virtuous person would characteristically do in the circumstances (i.e. acting in character).

(1') does not define (the concept of) moral rightness. It is only by identifying the property of being what a virtuous person, acting in character, would do in the circumstances with the right-maker of the action that one gets the virtue-ethical analysis:

(V) An action is right, if and only if, and because, it is what a virtuous person would characteristically do in the circumstances (i.e. acting in character).

Although a utilitarian can readily accept (1'), this theorist firmly rejects (V), since the right-maker in utilitarianism is the property of maximizing well-being:

(U) An action is right, if and only if, and because, it maximizes well-being.

But it is always possible that what a virtuous person, acting in character, would do in the circumstances systematically correlates with what maximizes well-being.

Likewise, it is always possible that the appropriateness to adopt some reactive attitude towards S in respect of A correlates with the fact that A is a part of S's moral record.

II. The Strawsonian view

I start with detailing the better-known Strawsonian conception. An understanding of the analysans of (S), involves further clarification of the issues surrounding the core concept of reactive attitudes and the appropriateness qualification. I will say something about the class of the reactive attitudes below. An elucidation of the qualification which stays close to Strawson's landmark paper (1962) is this:

(S') It is (or would be) appropriate to adopt some reactive attitude toward S in respect of A, if and only if, S has no excuse in respect of A and S him- or herself cannot be exempted (as abnormal or undeveloped).

S's being morally responsible consists in S's being held morally responsible in that S is subject to being targeted by reactive attitudes just in case S has no excuse or cannot be exempted. At first sight this elucidation is neutral with regard to the vexed issue of the compatibility or incompatibility of responsibility with determinism.

I now sketch a very limited and opinionated dialectic between three main versions of (S)/(S'): the Kantian, the Humean, and the Wittgensteinian version. These versions are defended, or at least set forth, by respectively R. Jay Wallace (1994), Paul Russell (2011) and Gary Watson (2014).

Wallace's normative version combines a Strawsonian account of holding responsible with a Kantian theory of practical freedom and moral agency. The appropriateness (or fairness) to adopt some reactive attitude toward S in respect of A is not explained in terms of S's having an alternative possibility B but in terms of S's possession of deliberative capacities needed for rational control in A-ing. This version involves a "narrow" construal of the class of reactive attitudes and an interpretation of responsibility within, what Bernard Williams calls, "the morality system" (1985 174-196). Holding responsible is directly connected to the violation of moral obligations and, further, exclusively linked to moral reactive attitudes such as resentment, blame and guilt. Non-moral attitudes such as sympathy and love as well as other ones such as gratitude and shame are expelled since they are not conditioned upon breaching strict moral expectations. As a result, responsibility belongs to a cluster of "thin" moral concepts such as obligation, right and wrong, blame and desert.

One of the gains is that the narrow approach cleans up some of the conceptual mess around the (threefold) distinction between attributability, answerability, and accountability. The morality system only countenances deontic and hypologic judgements to the exclusion of aretaic ones composed of "thick" moral concepts. In Watson's terminology, this system only shows responsibility's accountability face so as to exclude its attributability face (cf. 1996).

Russell argues that the costs of going narrow are probably too high. Wallace's narrow approach runs into difficulties not only about the implied asymmetry among the reactive attitudes but also about the western (even Christian) localism of the morality system (cf 2013). Moreover, Wallace's hybrid approach, blending Strawsonian and Kantian components, is in danger of opening up a gap between holding and being responsible. Someone might be responsible because he possesses the capacity for reflective self-control without being capable of holding himself and others responsible because he lacks the capacity for entertaining pertinent reactive attitudes. In view of these problems, Strawsonians should, according to Russell, better opt for a broader account of moral reactive attitudes and stop forcing responsibility into the reductive, thin straitjacket of the morality system.

Russell's own version explicitly joins a Strawsonian account of holding responsible with a Humean theory of moral sense.3 Attributions of responsibility are, according to him, forms of deep assessment because they are essentially connected to reactive attitudes. In his argument for the necessity of moral sentiments, Russell not so much focuses on the viewpoint of the responsibility-holder (the one who attributes responsibility) as he concentrates on the conditions that the one held responsible, the responsibility-target S, must satisfy (cf 2004). He supplements the standard Strawsonian version (S') with the necessary condition of moral sense: (S'+) It is (or would be) appropriate to adopt some reactive attitude toward S in respect of A, only if, S is capable of having and understanding reactive attitudes (moral sentiments), i.e. S is capable of seeing her- or himself and others as targets of the reactive attitudes.

Of course, on any version of (S'), the responsibility-holder necessarily has and understands moral sentiments. Since, in view of (S'+), the person held responsible -the responsibility-target S- also has and understands moral sentiments, Russell's Humean version assumes the reciprocity of targeting each other with reactive attitudes.

Although reciprocity remains important in Watson's version, Watson himself does not give primacy to the reactive sentiments but to, what he calls, "the basic demand" (2014 17). His version implicitly connects a Strawsonian account of holding and being responsible with, what I call a Wittgensteinian outlook on sociality.4

The fundamental idea here is that: "... our sense of ourselves and one another as morally responsible agents and (accordingly) as morally responsible to one another is integral to ("given with") human sociality itself" (Watson 2014 17). Two components of this sociality are crucial:

First, we care deeply (and "for its own sake") about how people regard one another. Second, this concern manifests itself in a demand or expectation to be treated with regard and good will. Following Strawson, let's call these the basic concern and the basic demand respectively. (Watson 2014 17)

The (social) demand is derived from the (social) concern. It is because the attitudes we take toward one another are of such a great concern to us, that we demand the presence of good will and the absence of ill will from one another. It follows that "[t]o be a responsible agent is to be someone whom it makes sense to subject to such a demand." (Watson 2014 17). The concern underlies the demand and "... it is only with the basic demand that a distinctive stance of holding responsible emerges." (id. 19). Making the demand is a stance that consists in some responsive disposition(s) but it should not be confused with actually having reactive attitudes such as resentment and indignation.

What then is the relation between the demand and the attitudes? According to Watson, Strawson himself makes a reductive claim: "The making of the demand is the proneness to such attitudes" (Strawson 1962 77). For Watson, however, the (social) demand is self-standing and has priority, even though the attitudes belong to the basic concern and possibly manifest themselves in reaction to the good or ill will displayed. It is in this sense that our commitment to holding and being responsible, which emerges with our commitment to the (social) demand, is integral not so much to our emotional nature as to our social nature: "there is no further fact about responsible action and agency beyond the realized capacity for interpersonal relations to which our responsibility practices are answerable" (Watson 2014 18).

In this way, Watson's version represents a kind of default-and-challenge position. Given our social nature, it suffices to be a responsible agent that one is a community member with the (realized) capacity to participate in reciprocal interpersonal relations. S is responsible (and held responsible) for the one and only reason that S is a member of the community capable of participation in reciprocal interpersonal relations. Just by being a member, S is ipso facto responsible (and held responsible). Sure enough, this default position can be challenged in exceptional circumstances when a plea for excuses or exemptions is called for. Normally, S is responsible. Exceptionally, S is not responsible and, in this negative case, only when S can be excused or exempted.

Although Watson himself does not give an explicit analysis, the gist of his considerations can be captured in the following rendition of (S):

(S*) Subject S is responsible for action A, if and only if, and because, a normal member of S's community would hold S responsible for A, barring excuses in respect of A or exemptions in respect of S.

We avoid circularity in this analysis by interpreting "holding responsible" in the analysans either as subjecting S to the basic demand or targeting S with reactive attitudes. A "normal" member is capable of participation in reciprocal interpersonal relations and capable of having and understanding reactive attitudes. It is not necessary that such a normal member actually holds S responsible; it suffices that he or she would do so given such-and-such circumstances (e.g. being present when S does A).

Since "a normal member of S's community" is an abstraction, one might ask whether any actual member in fact has the authority to hold S responsible?5 In response, an advocate of (S*) can adduce the following consideration. Any qualified, actual member can take up the role of a normal member who holds responsible. Yet, in that role the responsibility-holder is not proceeding on his or her own authority, nor on the authority of a particular group of members, but on the authority of the community as a whole. The authority to hold S responsible is grounded in the authority of what George Herbert Mead calls "the generalized other": "The organized community or social group which gives to the individual his [...] [personal responsibility] may be called 'the generalized other'. The attitude of the generalized other is the attitude of the whole community" (Mead 1934 154).

III. The Ledger View

Let us turn next to the less familiar ledger conception. Although the ledger view is less discussed and, as a result, appears to be the minority view, it is present in the contemporary debate much more than meets the eye.

The analysans of (L) needs further clarification on two scores. What is a person's moral record, or metaphorically, a person's "ledger of life"? What are the necessary and sufficient conditions for an action to be part of this record or ledger? For answers I turn to Michael Zimmerman, the chief representative of (L). He writes:

Moral [responsibility qua] appraisability has to do with that type of inward moral praising and blaming that constitutes making a private judgment about a person____Praising someone may be said to constitute judging that there is a "credit" in his "ledger of life," ... Blaming someone may be said to constitute judging that there is a "discredit" or "debit" in his "ledger," ... Someone is praiseworthy if he is deserving of such praise; that is, if it is correct, or true to the facts, to judge that there is a "credit" in his "ledger" [...]. Someone is blameworthy if he is deserving of such blame; that is, if it is correct, or true to the facts, to judge that there is a "debit" in his "ledger". It is important to note that, in the context of inward moral praise and blame, worthiness of such praise or blame is a strictly nonmoral type of worthiness; it is a matter of the truth or accuracy of judgments. (Zimmerman 1988 38)6

In light of this quote I try to elucidate the analysans.

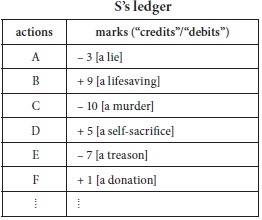

A person's moral record is an ideal, inward bookkeeping of that person's moral worth. Action A is part of S's moral record is short for the negative or positive "mark" in respect of A is part of S's moral record: a negative mark on some scale for an action that is wrong to some degree; a positive mark on some scale for an action that is right (or good) to some degree. As an illustration, consider the following imaginary ledger on a scale of +/- 10.

Furthermore, A is part of S's moral record when it is true to the facts to apply the relevant moral judgement to S in respect of A. The pertinent mark in respect of A does belong to S's moral record -S has the pertinent moral property- in case it is correct to ascribe the pertinent moral predicate to S in respect of A. Although the judgements themselves are moral, their correctness (worthiness or deservedness) is non-moral. In keeping the comparison with (S) as salient as possible, these elucidations yield:

(L*) Subject S is responsible for action A, if and only if, and because, it is (or would be) correct to judge inwardly S having a debit (or credit) on S's moral record in respect of A.

In unpacking the ledger metaphor Zimmerman warns us that "the metaphor is, at best, only suggestive" (1988 39):

There are no ledgers, or records of the sort mentioned-unless some vault in the heavens, guarded by God, contains them, and this is certainly not something that I am presupposing here. But even if there are no such records, it remains a fact that certain events occur and that a person's moral worth is a function of these events. A person can be praiseworthy or blameworthy without anyone's being aware of this, without anyone's taking note of it, without anyone's actually praising or blaming him. Indeed, the metaphor of the ledger can be misleading unless it is handled very carefully. Normally, when an ordinary person keeps a ledger, he makes the entries and he has a purpose in doing so; the entries are not somehow automatically recorded in the ledger, he being simply its custodian. But, if there were a ledger of life, its entries would not be made by anyone, nor would there be a purpose to the entries. (In saying this, I am again ignoring theological issues.) Rather, the entries would be automatically recorded; they would appear simply by virtue of certain events occurring (events of which the person's moral worth is a function). In this connection, we must particularly guard against thinking that inward praising and blaming are analogous to the making of entries in the ledger; on the contrary, they are analogous to judging there to be such entries (1988 39).

It is important not to take the ledger metaphor literally. Otherwise, one gets stuck in the mud of several spurious problems. For example, one could start wondering about the metaphysical constitution of the ledger-entries and the epistemic registration of these entries. What does it mean that entries are constituted fully automatically and that nobody needs to be aware of them? What does it mean that the judge is like a "custodian" not interfering in any way with the object of his judgement? And who is the custodian, who does the registration? Is it the individual S him or herself, we, or God? Given that the ledger metaphor is only suggestive, these are probably not relevant questions. Still, there certainly are specific metaphysical and epistemological presuppositions at work in the background. I will not pursue this point here, but it is fair to say that moral realism and ethical intuitionism go hand in hand with (L*).7

The literal content behind the ledger metaphor can be unpacked as follows. Take the analysans of (L*). When is it correct to judge S having some mark (debit or credit) on S's moral record in respect of A? It is correct so to judge S just in case it is true to the facts so to judge S. And it is true to the facts so to judge S just in case a certain proposition is true, or a certain truth-condition is satisfied. To express the pertinent proposition Zimmerman invokes the classical, Aristotelian elucidation of responsibility (or virtue) in terms of a knowledge and a control requirement. This specific analysis can be nested into the general analysis (L*): (L') It is (or would be) correct to judge S having a debit (or credit) on S's moral record in respect of A, if and only if, S knows that A is wrong (or right) and S has control in A-ing.

On the ledger view, both these requirements are part of the analysis of moral responsibility. The further interpretation of the epistemic and the freedom condition is, of course, highly controversial. This controversy is of no concern to this paper.

IV. Contrasting Views

I now contrast the ledger with the Strawsonian conception. First, (S) [(S')/(S'+)/(S*)] is a relational view, whereas (L) [(L*)/(L)] is an intrinsic view. Apart from self-directed reactive attitudes (self-reactive attitudes such as feeling guilty or remorseful), the relevant class of attitudes is other-directed (e.g. resentment and indignation). Reactive attitudes are, first and foremost, responses to the quality of will of other people as expressed in their behaviour. This relational or interpersonal feature is wholly absent from (L). The entries in the ledger are intrinsic; they are present entirely independent of other people's reactions, attitudes or even awareness. The precise and correct judgements constituted by inward appraisals are private. What matters is the truth or falsehood of a certain proposition, and nothing else.

Secondly, (S) is an emotional view, whereas (L) is a cognitive view.8 The relevant class of reactive attitudes is a subclass of moral emotions. Although Strawsonians do not necessarily deny the propositional structure of the attitudes, (to my knowledge) they do not adhere explicitly to the cognitive theory of the emotions. In general, it is fair to say that (S) borders on moral emotivism. Such a reliance on moral sentiment is wholly absent from (L). Judging moral facts or believing moral propositions is unemotional. And the correctness of the judgements and beliefs is epistemic (non-moral).

Thirdly, and also in the light of the two foregoing points of contrast, (S) appears to be a view on holding responsible and being held responsible, whereas (L) appears to be a view on being responsible. (S) can, at most, account for our holding responsible and our being held responsible, because responsibility as based on interpersonal reactive attitudes depends on contingent, relational and emotional elements which are always to some degree conventional and arbitrary. In so far as (S) aspires, in addition, to be a view on being responsible, it equates appropriately being held responsible with being responsible. (L) keeps these two things strictly apart. Our reactive attitudes and related practices (such as punishment) are one thing, being responsible as based on intrinsic and cognitive elements is another thing. In so far as a view makes the distinction between holding and being responsible, or associated distinctions such as that between outward and inward blaming and that between active and passive blaming, a ledger conception of responsibility plays, at least tacitly, a structuring role in the background. Although ledger-theorists do not deny the contingent connection with the reactive attitudes (they can accept (1)), being responsible -"real" and "genuine" responsibility- is independently constituted and prior to holding responsible.

V. Which Is The Right View?

(S) and (L) are clearly different and, at first sight, conflicting conceptions of responsibility. Yet, both (S) and (L) seem to be intelligible and coherent. If (S) and (L) as a pair form an exclusive disjunction, then one of both conceptions must be wrong. Which is the right one? A full evaluation of both conceptions is beyond the scope of this paper. I will only raise three central issues.

First, there is an issue about the theoretical stability of (S). (S) is in danger to collapse because, on a closer look, it seems to shade into (L), directly or indirectly. A natural way to understand the appropriateness clause in

Subject S is responsible for action A, if and only if, and because, it is (or would be) appropriate to adopt some reactive attitude toward S in respect of A.

is eventually in terms of (L'), i.e. by an appeal to the satisfaction of the knowledge and control condition. If S knows that A is wrong (or right) and S has control in A-ing, then one is justified to adopt some reactive attitude toward S in respect of A.

But also more indirectly, there is the threat that (S) shades into (L). Take again:

(S') It is (or would be) appropriate to adopt some reactive attitude toward S in respect of A, if and only if, S has no excuse in respect of A and S him- or herself cannot be exempted (as abnormal or undeveloped).

According to Strawson (1962 64), there are two kinds of special considerations that modify (or mollify) or remove altogether the stance of holding responsible: excusing and exempting considerations. Holding S responsible does not seem natural or reasonable or appropriate when S has an excuse (or acceptable justification) in respect of A or when S him- or herself is exempted from responsibility.

But now we can ask further under which conditions persons are excused or exempted. Take excuses:

To the first group belong all those which might give occasion for the employment of such expressions as "He didn't mean to", "He hadn't realized", "He didn't know", and also all those which might give occasion for the use of the phrase "He couldn't help it", when this is supported by such phrases as "He was pushed", "He had to do it", "It was the only way", "They left him no alternative" etc. (Strawson 1962 64, italics added)

John Martin Fischer (2014 98) argues that it is natural to interpret the end of this passage (in italics) -which he calls "those pesky modal claims" (100)- in terms of the metaphysical condition of "could (not) have done otherwise". So, it turns out that excuses cannot be understood without bringing in one or other version of the control condition. Likewise, it seems that we cannot get a grip on exemptions -being exempted as abnormal or undeveloped- in the absence of the control and knowledge condition. If the Strawsonian paradigm needs to include a theory of volitional and cognitive capacities to differentiate between those who are exempted and those who are not, then it will get embroiled in the debate on moral and/or metaphysical capacities and abilities. Consequently, if a further analysis of (S') were inevitably give rise to considerations about the knowledge and/or control condition, then (S') would shade into (L'). Furthermore, the prima facie advantage of (S)'s neutrality with regard to the vexed issue of the compatibility or incompatibility of responsibility with determinism would be lost.

In the light of (S)'s instability, one could wonder, for example, how Fischer's semi-compatibilism should be categorized. Is it an explicit version of (S), or an implicit version of (L)? I hesitate to categorize Fischer's semi-compatibilism as a clear version of (S). Although Kane (cf. 2005 115-119) classifies Fischer (and Ravizza 1998) as a reactive attitude theorist, Fischer (2014) himself draws back from Strawson's extreme sequestration of metaphysics. And although Fischer and Ravizza in the beginning of their Responsibility and Control book explicitly adopt the Strawsonian conception (cf. 1998 5-9), in the rest of the book one cannot find much discussion of the role of reactive attitudes or the importance of a moral community, except in the chapter on "taking responsibility" (cf. 208214). The main discussion is about (moderate) reasons-responsiveness in an attempt to detail the control condition. It is only in connection to "historical" concerns about "ownership" that they mention the subjectivist requirement that the agent must be able to see herself as an appropriate target of moral sentiments. Maybe Fischer wants to stay noncommittal between (S) and (L), but that lingering position in itself might be interpreted as a form of instability.

However, Strawsonians might respond that this theoretical instability is only a temporary weakness of (S) to be overcome in the future. Theorists who are sympathetic towards Strawson's own original contribution can readily admit that there still remains a lot of mop-up work and puzzle-solving to be done in the Strawsonian paradigm. Indeed, one important class of puzzles still besets the investigation of "excuses". The development of a satisfactory account of excuses and exemptions is crucial for the stability of the Strawsonian paradigm.9

Secondly, Strawsonians raise the objection of shallowness (or superficiality) against (L). The common ground between all versions of (L) is the general strategy to distinguish being responsible from holding responsible, or putting it otherwise, to prioritize the "metaphysics" of responsibility over the "practice" of responsibility. The implication of this strategy is the thought that it is possible to make sense of attributions of responsibility independent and in isolation from reactive attitudes and expressions of these moral emotions in practices of blaming and punishing.

Now, according to Russell, such an isolation of being responsible from holding responsible "leaves our understanding of what it is to be responsible incomplete and one-sided -lacking the needed and necessary psychological linkage between agent and judge" (Russell 2011 213). Following Wallace, he formulates the objection of shallowness against any view that severs the connection between being and holding responsible (cf 1994 77-83). On such views, attributions of responsibility would lack the special force and depth they normally have in our moral dealings with each other: "By severing our assessments of culpability and fault from their (natural) connections and associations with conditions of (active) blame we erode the very fabric of moral life, and strip away the evaluative significance and motivational traction of moral judgment" (Russell 2011 213). According to (S), then, attributions of responsibility are forms of deep assessment because they are connected to reactive attitudes.

However, one might argue that the objection rest on a simple misunderstanding of the scope of (L). (L) is not restricted to judging some proposition about an agent to be true or false. Sure, the truth or falsehood of the proposition that S knows that A is wrong (or right) and S has control in A-ing is absolutely crucial. Yet, (L*)/(L') is perfectly compatible with the biconditional or correlation formulated in section 1: (1) Subject S is responsible for action A, if and only if, it is (or would be) appropriate to adopt some reactive attitude toward S in respect of A.

(L) allows for a systematic correlation between the truth or falsehood of the proposition that S knows that A is wrong (or right) and S has control in A-ing, on the one hand, and the adoption of some reactive attitude toward S in respect of A, on the other. True, having a reactive attitude does not belong essentially to judging a proposition true or false. But, it is not clear what else would be needed besides the systematic correlation (1) to turn attributions of responsibility also into forms of deep assessment. Moreover, the attribution of responsibility based on such a judgement can then justify the deep assessment based on reactive attitudes. Derk Pereboom, for instance, also a ledger-theorist, implicitly seems to appeal to the biconditional (1) when he writes:

in my view, for an agent to be morally responsible for an action is for this action to belong to the agent in such a way that she would deserve blame if the action were morally wrong, and she would deserve credit or perhaps praise if it were morally exemplary. ... I oppose the idea that to judge a person morally responsible essentially involves having an attitude toward her. Rather, I think that to make a judgment of this sort is most fundamentally to make a factual claim. ... It is of course consistent with the view that judgments about moral responsibility are factual that such judgments are typically accompanied by attitudes (Pereboom 2001 XX).

Thirdly, there is the important issue of priority or "the order of explanation".10 Strawsonians often stay in the dark about the precise biconditionals and grounding relationships. But in general the baseline of (S) is clear enough. One cannot make sense of attributions of responsibility independently of and in isolation from reactive attitudes and their expressions in practices of blaming and punishing. So, according to Strawsonians, reactive attitudes come first in the order of explanation and blameworthiness (responsibility) second. One can only be blameworthy because one is an appropriate target for reactive attitudes. By contrast, the ledger-theorists reverse the order of explanation so that blameworthiness comes first and reactive attitudes second. Remember that (L) and (1) are compatible. One can only be an appropriate target for reactive attitudes because one is blameworthy.

To resolve this disagreement, we need an answer to the crucial question: What is actually prior? What is really more fundamental? From the baseline of (L), the truth of the matter seems obvious because there are fatal counterexamples against (S).

Consider again Russell's necessity of moral sense:

(S'+) It is (or would be) appropriate to adopt some reactive attitude toward S in respect of A, only if, S is capable of having and understanding reactive attitudes (moral sentiments), i.e. S is capable of seeing her- or himself and others as targets of the reactive attitudes.

Take Bill who tortures a kitten just for the fun of it. He does this freely and knows that torturing animals is wrong. After the kitten died, Bill who is capable of having and understanding reactive attitudes feels guilty and deems himself worthy of being blamed by others. Now compare Bill with Ben. Ben is fully type-identical with Bill as to mind and action, except that he does not have self- or other-directed reactive attitudes. Ben lacks these attitudes because the neural network upon which a moral sense normally supervenes is not operative in his case. Would Ben, therefore, be off the hook? Intuitively, as long as Ben tortures freely and knows that torturing animals is wrong he seems to be as blameworthy as Bill for torturing the kitten. Hence, (S'+) is superfluous. Or consider again Watson's community view: (S*) Subject S is responsible for action A, if and only if, and because, a normal member of S's community would hold S responsible for A, barring excuses in respect of A or exemptions in respect of S.

Take Bill*, the sole human survivor after a global atomic war, who also tortures a kitten -the sole surviving one- just for the fun of it. He also does this freely and knows that torturing animals is wrong. There is no other single human being and thus no moral community left on earth. Would Bill*, therefore, be off the hook? Intuitively, as long as Bill* tortures freely and knows that torturing animals is wrong he still seems to be fully blameworthy for torturing the kitten. So, (S*) is spurious.

However, Strawsonians could dig in their heels. From the baseline of (S), they just have the opposite intuitions in these cases. Ben and Bill* are not blameworthy, precisely because the one lacks the necessary reactive attitudes and the other is deprived of all community life. In their defence, Strawsonians might suggest that Benn is on a par with some psychopaths who would be exonerated from blame because of their lack of moral sense. Furthermore, they might suggest that blaming Bill* is as problematic as executing the last murderer in Kant's abandoned island case: "Even if a civil society were to be dissolved by the consent of all its members (e.g. if a people inhabiting an island decided to separate and disperse throughout the world), the last murderer remaining in prison would first have to be executed" (Kant 1797 142). Blameworthiness just is a relational property which breaks down when one term of the relationship ceases to exist.11

VI. Open-Ended Conclusion

One pessimistic conclusion would be that we are stuck in a deadlock of intuitions. What other possible considerations, apart from intuitions, could be advanced to settle the disagreement between (S) and (L)? Another conclusion would be that the exclusive disjunction between (S) and (L) is actually an inclusive one and thus that both views are partially right. Neither (S) nor (L) has fully the truth at its side. Still another, more optimistic conclusion would be that the jury is still out about which analysis of the concept of responsibility is the right one. Perhaps we first have to do more work on getting the analyses as complete and as clear as possible.