INTRODUCTION

Tropical forests provide goods and ecosystem services that benefit the communities inhabiting these ecosystems; however, uncontrolled exploitation of wood and non-wood forest products drastically affects biodiversity and the abundance of certain native species (Palacios and Jaramillo, 2016). Indiscriminate deforestation reduces the number of seed trees; therefore, risking the future genetic base and seed propagation (Rojas, 2015). Furthermore, the scarcity of information about native forest species' propagation greatly adds to this problematic (Amaral et al., 2017).

Most tropical forest species propagate sexually; therefore, phytosanitary and genetic aspects are important to obtain quality seedlings that meet commercial expectations (Nascimento et al., 2019). However, many native species are not included in forest production plans and assessments of pre-germination treatments, which is likely due to limited information in rural settings or restricted access to seeds. Furthermore, several industries, environmental authorities, and nursery growers require information about forest seeds' adequate management to achieve efficient and low-cost propagation (Nascimento et al., 2019).

Carapa guianensis Aubl. (Meliaceae), known as andiroba in Brazil (Gonçalves et al., 2018) and tangare in the Pacific coast of Nariño in Colombia, is a promising native species of rapid growth, reaching a maximum height of 55 m. It is distributed in South America and is native to the Amazon rainforest (Leite and Lima, 2018). This species displays important ecological characteristics, and high commercial value due to its wood and medicinal properties (Gonçalves et al., 2018; Reis et al., 2018) since the oil extracted from its seeds has pharmaceutical applications (Reis et al., 2018). Reproduction is mainly sexual (Lobo and Furtado, 2015); the fruit is a spherical capsule composed of eight seeds that animals disperse (May 2016; Gonçalves et al., 2018; Leite and Lima, 2018). Seed harvesting is generally done by local communities who lack training regarding seed management, collection methods, or the plant population's analysis or successional structure (Guarino et al., 2014).

The exceptional characteristics of C. guianensis promote its high use; however, this exploitation considerably affects its population size and natural areas. Therefore, information about germination dynamics and seed morphology are important to establish seed collection and management guidelines to successfully propagate this species (Abbade and Takaki, 2014; Peixoto et al., 2019). For C. guianensis¸ germination behavior is variable; for instance, 24% to 90% germination can be reached in different periods ranging from days to months (Kossmann et al., 2002; Amaral et al., 2017; Hernández-Coronado et al., 2018). Therefore, nursery propagation alternatives for this species have led to the use of different pre-germination treatments such as mechanical scarification, sunlight exposure, and seed imbibition in sand and soil substrates (Torres et al., 2017). These methods provide adequate conditions to accelerate and increase germination of the embryo (Viveros et al., 2015).

In this context, and as part of the project entitled “Planification and management strategies for forest plantations in agroecosystems of Colombia”, Corporación Colombiana de Investigación Agropecuaria (Colombian Corporation for Agricultural Research) - AGROSAVIA developed this study to evaluate to evaluate seed germination of C. guianensis under different pre-germination treatments and substrates in nursery conditions at the Centro de Investigación El Mira of AGROSAVIA.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Location. This study was conducted at the Centro de Investigación el Mira of the Corporación Colombiana de Investigación Agropecuaria (AGROSAVIA), which is geographically located at 78°41’22’’N and 1°32’58’’W, in Tumaco, Department of Nariño (Colombia). The study site is situated at an elevation of 16 m a.s.l., with a mean precipitation of 3067 mm/year, mean temperature of 25.5°C, and relative humidity of 88% (Reyes et al., 2008).

Seed collection. This study used seeds from Salahonda in the municipality of Francisco Pizarro (Nariño) at 2°02′30″ N and 78°39′40″ W. The seeds were collected from 10 trees according to the methodology described by Espitia-Camacho et al. (2018) . The selected trees were visibly healthy and vigorous, with straight, long and accessible trunks, as Torres et al. (2017) recommended.

Physical description of the seed. A general description was made of the total seed lot based on eight samples composed of 100 units each, which were individually weighed on a Mettler Toledo tenth of a gram digital scale (Asociación Internacional de Pruebas de Semillas-ISTA, 2005; Espitia-Camacho et al. 2018). Next, the biometric properties of the seeds from each repetition were determined based on the following variables: width (mm), length (mm), and thickness (mm), measured using a Mitutoyo digital caliper. Diseased and infected seeds were discarded (Hernández-Coronado et al., 2018) (Figure 1).

Pre-germination treatments and substrates. Three pre-germination treatments and a control were performed (Table 1). According to the study by García et al. (2019) , the pre-germination treatments were selected for tropical forest species. The substrates were selected based on Lobo and Furtado (2015) , with modified proportions.

Table 1. Pre-germination treatments and substrates used for propagating C. guianensis.

| Pre-germination treatments | Substrate |

|---|---|

| T1: control without treatment | S1: sand (100%) |

| T2: sunlight exposure for 24h + imbibition for 24h | S2: sand and soil (50%-50%) |

| T3: mechanical scarification | S3: soil (100%) |

| T4: mechanical scarification + imbibition for 24h |

The substrates were disinfected with dazomet (Theaux, 2015) at a dose of 40g per m2; then, the substrate was covered with plastic for five days and left to settle for 12 more days.

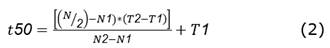

Experimental design. A randomized blocks design with split-plots and four repetitions was implemented. The large plots corresponded to the substrates, namely sand (S1), sand and soil (S2), and soil (S3) (Santiago et al., 2015). Furthermore, the subplots corresponded to the seed treatments: control without treatment (T1), T2: sunlight exposure for 24h + imbibition for 24h (T2), mechanical scarification (T3), and T4: mechanical scarification + imbibition for 24h (T4). In total, 12 combinations were obtained, and the experimental unit was 20 seeds/pre-germination treatment for a total of 960 seeds (ISTA, 2005) (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Split-plots design: the main plot = substrates (S1, S2, S3), the subplots = treatments (T1, T2, T3, T4) and four repetitions (R1, R2, R3, R4).

The effects of the pre-germination treatments and substrates were measured as the cumulative germination percentage (CGP) and mean germination time (t 50 ) (Lobo and Furtado, 2015). Furthermore, the initial and final germination percentages were determined (Torres et al., 2017). After planting, the number of germinated seeds was recorded daily until day 42 (i.e., when germination remained constant). A seed was considered to have germinated when the epicotyl grew to at least 1cm (Céspedes, 2018).

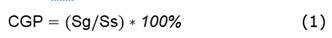

The CGP was calculated per experimental unit for each substrate, according to equation 1:

Where:

Sg= Number of germinated seeds and

Ss= Number of planted seeds.

The t 50 was calculated according to equation 2 proposed by Ellis and Roberts (1978). This equation establishes the time needed to reach 50% seed germination (Sánchez-Soto et al., 2017).

Where:

N = Final % of germinated seeds.

N1 = % of germinated seeds prior to N/2.

N2 = % of germinated seeds after to N/2.

T1 = Number of days for N1.

T2 = Number of days for N2.

t 50 = Number of days for N/2.

Statistical analysis. The statistical tests were performed using InfoStat version V. 2016. The variables were tested for normality, using the Shapiro-Wilk test and Q-Q plots, as well as homoscedasticity. The treatments, substrates, and their interaction (treatments with substrates) were analyzed by a variance analysis (ANOVA), followed by Tukey’s multiple comparison test. This same analysis was performed for the time of onset of germination and meantime of germination. P-values less than 0.05 were considered significant (P < 0.05) (Zar, 2010).

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Physical description of the seed. The seed weight of C. guianensis varied within a broad range (i.e., from 23.36g to 49.60g), with an average of 35.7g. This value is higher than reported by Hernández-Coronado et al. (2018) , who found an average weight of 22.1g based on 100 seeds. Similarly, Kossmann et al. (2002) reported weights between 25 and 32g and established that 30-50 seeds are required to obtain 1kg. In this study, the data indicates that approximately 28 seeds are required per kg. Peixoto et al. (2019) found different weights for C. guianensis, even seeds from the same fruit, and determined that this variability could be associated with the non-domestication of this species.

The other biometric parameters, such as length, width, and thickness of C. guianensis seeds, (Table 2) also showed higher variation than in Teixeira et al. (2019) , who reported mean values 38.21, 33.56, and 32.95mm, respectively. Several researchers indicate that the agroclimatic conditions of the site can affect seed development, leading to variations in seed size, weight, and morphology (Peixoto et al., 2019). Based on the results shown in Table 2, this seed can be considered extremely large compared to other forest seeds, according to the manual of tropical and subtropical seeds of ISTA (2005).

Table 2. Biometric data of the seed of C. guianensis.

| Variable | Mean value ± SD |

|---|---|

| Weight (g) | 35.7± 6.07 |

| Length (mm) | 59.1±3.59 |

| Width (mm) | 54.8±3.28 |

| Thickness (mm) | 43.2±4.16 |

SD: Standard deviation.

Evaluation of germination. The CGP did not show significant differences in response to the substrate (P=0.9453); therefore, this variable did not affect germination. These results differ from reports by Severino et al. (2005) indicated that forest seeds’ germination depends on the substrate since it provides different physical factors such as aeration and humidity. The pre-germination treatments showed significant differences in CGP (P<0.0001), as well as the interaction between substrates and pre-germination treatments (P<0.0096) (Table 3).

Table 3. Results of the analysis of variance (ANOVA) for the split-plots.

| F of V | DF | P-value |

|---|---|---|

| Model | 20 | <0.0001*** |

| Substrates | 2 | 0.9453 ns |

| Error Factor A | 9 | 0.0018 |

| Treatments | 3 | <0.0001*** |

| Interaction | 6 | 0.0096** |

| Error Factor B | 27 | - |

| Total | 47 | - |

F of V; factor of the variable. DF; degrees of freedom. p: probability limits of the ANOVA. **: P < 0.01; ***: P < 0.001; ns: P > 0.05. R squared = 0.93. CV= 24.25 Factors: factor A: substrates on germination % and factor B: treatments on germination %.

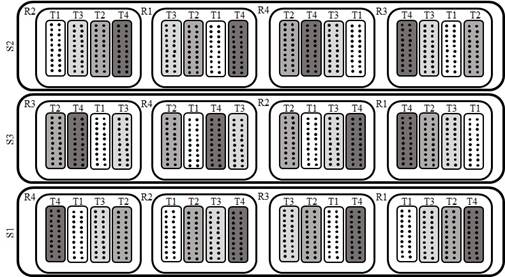

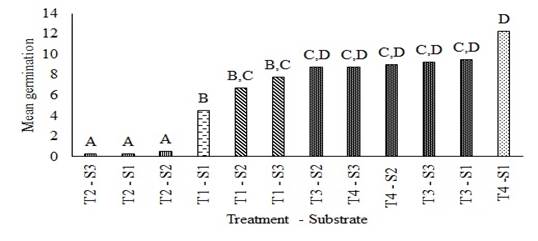

For pre-germination treatments, Tukey’s multiple comparison test indicated that treatments T3, and T4 had the highest values with similar means; therefore, these treatments do not differ and either pre-germination method is suitable (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Cumulative germination per pre-germination treatment. Tukey’s multiple comparison test. Different letters above the columns indicate a significant difference (Tukey. P < 0.05).

According to Figure 3, T2 does not promote germination; this finding differs from Lobo and Furtado (2015) reports. These authors assessed the effect of different levels of sunlight on C. guianensis and established that germination is significantly promoted under all light intensity levels. Bewley et al. (2013) mention that sunlight exposure can cause water deficits in seeds, affecting the velocity and final germination percentage andgermination variability. The results found here suggest that sunlight exposure likely induces photoinhibition of germination; thus, negatively affecting propagation. Several authors suggest that this type of seeds should be planted immediately after collection (Sánchez et al., 2015).

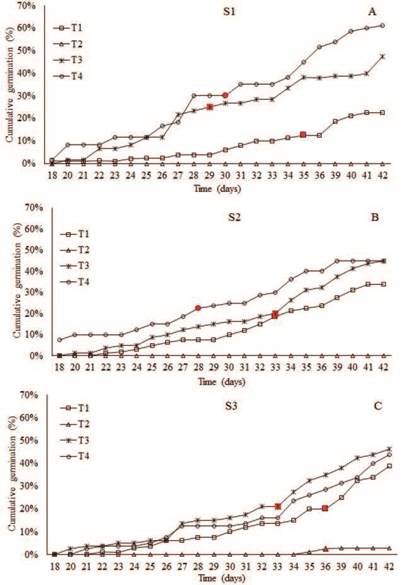

Tukey’s multiple comparison test for the interaction between treatments and substrates (Figure 4) indicated five groups (A, B, BC, CD, D). Furthermore, T4 in S1 shows the highest mean germination ( x =12.25), equal to 61% germination. The cumulative germination percentage (Figure 5) was congruent with this result; accordingly, T4 in S1 showed the highest germination percentage than other substrates and treatments. Overall, C. guianensis was found to germinate gradually, which agrees with reports by Villota (2016) and Hernández-Coronado et al. (2018).

Figure 4. Cumulative germination for pre-germination treatments and substrates interaction. Tukey’s multiple comparison test. Different letters above the columns indicate significant differences (Tukey. P < 0.05).

Figure 5. The Behavior of the cumulative germination percentage of C. guianensis. A: S1; B: S2; C: S3 under pre-germination treatments: T1; T2; T3; T4. Shapes in red: mean germination time (t 50 ).

No significant differences (P=0.32) were found for the initial germination percentage, as shown in Figure 5. However, the highest value was found for T4 in S2, it reached 8% germination on day 18 of the experiment (Figure 5B). Villacorta (2010) reported the same results and determined that this species' onset of germination occurred on day 18 after planting, based on a previous imbibition treatment for 48 hours at room temperature. However, these results differ from those found by Vianna (1982) , who assessed the behavior of Andiroba seeds in Tapajos National Forest (Santarém. PA). The author reported that onset of germination occurred at day 1, without applying pre-germination treatments. Conversely, Villota (2016) reported that the onset of Carapa amorphocarpa W., a species of the same family, occurred on day 43 in sand + soil substrate. Sanchez et al. (2019) indicated that C. guianensis develops better in very humid substrates, such as soil, storing and retaining moisture.

Regarding the final germination percentage (Figure 5), T4 in S1 reached 61% after 42 days (Figure 5A), while T2 showed 0% to 3% germination in the same period. These results exceed those reported by Kossmann et al.(2002) . He determined that C. guianensis only reached 30% germination in 40 dayswithout any treatment. Scarano et al. (2003) mention that 88% of seeds germinated after 30 days, 82% after 2 months, and 70% after 90 days after a flotation technique applied to different seed lots of C. guianensis.

There were no significant differences (P=0.24) in t 50 for the total number of germinated seeds. The mean germination time ranged from 28 to 36 days. The lowest value was obtained for T4 in S2 (t 50 =28 days with 23% germination), indicating that less time was required to reach 50% germination than in other treatments and substrates. Meanwhile, T2 in S3 (t 50 =36 days with 3%) showed the highest mean germination time. Nevertheless, this result is lower than Myers (2013) reported because he found a mean germination time of 65 days of C. guianensis. The results differ from those reported for Swietenia macrophylla King., a species of the same family (Meliaceae) since it displays a germination time ranging from 8 to 14 days (Céspedes, 2018). Therefore, seed germination and establishment requirements are species-specific and are influenced by the characteristics of the region that the species has adapted to (Sánchez et al., 2019).

CONCLUSIONS

The C. guianensis seeds’ biometric characteristics from Tumaco-Nariño allow classifying the seeds as relatively large (weight: 35.7g, length: 59.1mm, width: 54.8mm, and thickness: 43.2mm).

A comparison of the CGP of C. guianensis reported in different studies, including this study, shows that germination is highly variable and likely depends on agroecological conditions.

By comparing the CGP with other studies, we determined that germination of C. guianensis is highly variable and it likely depends on the agroecological conditions of the site. Therefore, in ecosystems similar to the one found in Tumaco-Nariño, the interaction of mechanical scarification + imbibition for 24h in sand substrate allows cumulative germination of 61%.

The mean germination time ranged from 28 to 36 days; however, it was not affected by the pre-germination treatments and substrates used, indicated by non-significant differences.