Serviços Personalizados

Journal

Artigo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Acessos

Acessos

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares em

SciELO

Similares em

SciELO -

Similares em Google

Similares em Google

Compartilhar

Revista Latinoamericana de Psicología

versão impressa ISSN 0120-0534

rev.latinoam.psicol. v.44 n.1 Bogotá jan./abr. 2012

Todd Ward

University of Nevada, Reno

Contact Person: Ramona Houmanfar. Department of Psychology, Mail Stop 296, University of Nevada, Reno, Reno, NV 89557, Email: ramonah@unr.edu, Tel: (775) 682-8693

Author Note: Requests for reprints can be sent to Ramona Houmanfar, Department of Psychology, Mail Stop 296, University of Nevada, Reno, Reno, NV 89557

Recibido: Agosto 8 de 2011 Revisado: Octubre 24 de 2011 Aceptado: Diciembre 8 de 2011

Resumen

Los temas de este trabajo son el papel de las prácticas religiosas en la evolución cultural y las interrelaciones entre las prácticas religiosas y otras prácticas culturales. En ese sentido, las prácticas religiosas y no religiosas interactúan en diversas formas que pueden o no ser importantes o necesarias para su mantenimiento. La preservación de prácticas particulares por la manipulación deliberada de estas interrelaciones es frecuente. Se presume que la motivación de las autoridades con el poder de manipular las prácticas se centra en el valor de los resultados producidos. Ese valor, explícita o implícitamente, es la supervivencia del grupo o la supervivencia cultural. Este trabajo proporciona un análisis descriptivo de las condiciones socioeconómicas e históricas que generan las prácticas religiosas asociadas con el martirio. Nuestro análisis toma el contacto interdisciplinario entre el análisis de la conducta y ciencias sociales tales como la sociología y la antropología utilizando los conceptos de metacontingencia y macrocontingencia. Abordamos la importancia de esta interacción para las prácticas religiosas como el martirio en la supervivencia grupal o cultural, y concluimos con una discusión de los retos que los analistas del comportamiento enfrentan como ingenieros culturales.

Palabras clave: Martirio, metacontingencia, macrocontingencia.

Abstract

The role of religious practices in cultural evolution and the interrelations of religious and other cultural practices are the topics of this paper. In that regard, religious and non-religious practices interact in a variety of ways and may be important or necessary for the maintenance of each. The preservation of particular practices by the deliberate manipulation of these interrelations is commonplace. Presumably, the motivation of authorities with the power to manipulate practices is centered on the value of outcomes produced. That value, explicitly or implicitly, is group survival or cultural survival. This paper provides a descriptive analysis of the socio-economic and historical conditions that generate religious practices associated with martyrdom. Our analysis draws upon interdisciplinary contact between behavior analysis and social sciences such as sociology and anthropology by utilizing concepts of metacontingency and macrocontingency. We address the significance of this interaction to the role of religious practices such as martyrdom in group survival or cultural survival and conclude with a discussion of the challenges facing behavior analysts as cultural engineers.

Keywords: Martyrdom, metacontingecny, macrocontigency.

Cultural Survival or Group Survival? A Behavioral Account of Martyrdom as a Religious Practice

More than 80% of all suicide bombings since 1968 have occurred after the 9/11 attacks (Atran, 2006). Although suicide attacks, and attacks by religious groups more generally, do not constitute the majority of terrorist attacks, they do generate the majority of all casualties (Atran, 2006; Piazza, 2009). According to Piazza's (2009) analysis of terrorist attacks from 1968-2005 religious groups inflicted casualties (38.10 per attack) more than secular leftist, rightist, and national-separatist groups (2.41-9.82 per attack). Of attacks by religious groups, Islamist groups were responsible for over 90% and were responsible for roughly 87% of all casualties (20.7 victims vs. 8.7 victims for non-Islamic groups).

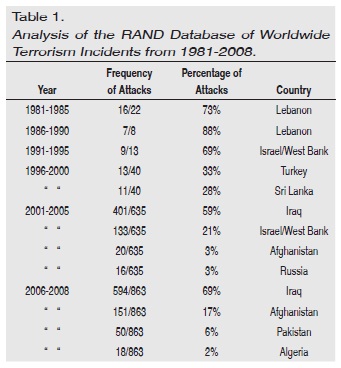

We conducted an analysis of global suicide attacks at five-year increments from 1981-2008 based on data from the RAND Database of Worldwide Terrorism Incidents. As depicted in Table 1, the attacks were centered primarily in Lebanon throughout the 1980s with a shift to Israel and the West Bank in the early 1990s, followed by Turkey and Sri Lanka in the late 1990s. At the turn of the century the attacks were overwhelmingly focused in Iraq. Excluding Iraq, however, we found diversification in the countries with the highest rates of suicide attacks, which included Afghanistan, Pakistan, Russia, and Algeria. In this paper we provide a descriptive analysis of the geopolitical, socio-economic and historical conditions that generate religious practices associated with martyrdom. By placing an emphasis on suicide bombings and their relation to religious practices, we will offer a brief history of the evolution of martyrdom. Additionally, we will discuss the relation of such religious practices to cultural leaders' opportunistic decision-making behaviors. Our analysis draws upon distinctions between religious and non-religious, plus religious and moral practices, and addresses the reciprocal relationship between psychological and sociological levels of analysis.

A Brief History of Martyrdom

The practice of martyrdom entails sacrificing "something of great value, especially life itself, for the sake of a principle" (martyr, 2010) and has its roots in the ancient Greek and Roman empires, which have similar characteristics and occur in the same general region as most modern day suicide bombings. One form, called suicide by execratio, was prevalent in ancient Rome and was based on the belief that the spirit of the dead person could harass people and communities in the afterlife. It was not uncommon for ancient defeated armies to blame curses placed upon them by suicides. This practice was also found among Roman slaves. In sum, execratio was thought to be a form of revenge on those who have made their lives miserable and a way for politically powerless people toinfluence those with power (Preti, 2006).

Whereas suicide by execratio involved self-inflicted death, a second form of suicide known as Samsonic suicide involved the direct destruction of the enemy in the process. Samsonic suicide gets its name from the Biblical Samson who receives the strength from God to kill himself and his enemies by destroying the palace where he was imprisoned. The famous battle of Thermopylae is thought to be another example of Samsonic suicide. In 480 BC a few thousand Greeks faced certain death as they held off a Persian army of more than a million men for three days, which resulted in the virtual annihilation of the Greeks at a cost of 20,000 Persian men. A third type is called suicide devotio whereby a soldier is required to inform his fellows, speak a ritualistic curse against his enemies, and throw himself against the enemy to kill as many as possible, which always resulted in the individual's death. In devotio victory and one's own salvation were expected to follow the annihilation of the enemy (Preti, 2006).

In the 20th century, the first major incidence of martyrdom occurred in World War II during the Okinawa campaign. Nearly 2,000 suicide attacks took place by Japanese kamikaze pilots (meaning "divine wind") who loaded their planes with bombs and few them directly into ships in April and June of 1945. With 368 ships damaged and 32 sunk, nearly 5,000 Americans were killed and the same number wounded, the battle of Okinawa proved to be the most costly in the history of the U.S. Navy and produced the heaviest losses in any naval campaign during WWII (Preti, 2006).

After WWII, notable instances of martyrdom include the 1963 self-burning of Vietnamese monk Thich Quang Duc as a protest against the Vietnam War. The first major suicide bombing in the Middle East after WWII occurred in Beirut, Lebanon in December of 1981, which destroyed the Iraqi embassy, left 27 dead and 100 wounded. Since then, suicide bombings have become a strategic political weapon, primarily directed to the West and Israel, with the deadliest attack occurring in New York on September 11, 2001, which left over 3,000 dead (Preti, 2006).

Since the 9/11 attacks, terrorism has typically been associated with young Muslim men assumed to be ill-educated fanatics seeking virgins in paradise, which may be true in some cases, but the reality is far more complex. One factor believed to play a role in modern day terrorism is a lack of voice in society. Dictatorships, common in the Middle East, tend to crush opposition groups while the youth tend to believe the dictatorships to be supported by the United States. Forms of opposition not attacked by the government are those in the mosque, which tend to favor religious fundamentalism. One possible exception to this is Hamas, who gained political control in Palestine and speak out against corrupt Arab leaders. Related to this, instances of Palestinian violence against Israel relates to protecting family honor, and important value in Middle East culture, evoked by one seeing family members arrested or even shot by Israeli soldiers. In these cases, violence seems to be the only path to being heard (Blake, 2009; Christensen, 2009; Mattaini, 2003; Sidman, 2001).

Martyrdom and Islam

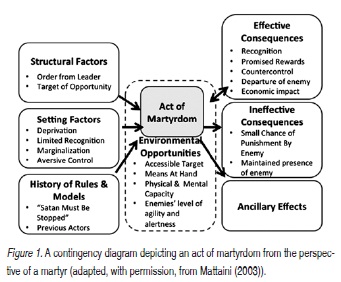

Most Islamic scholars argue that the Koran forbids suicide (Wright, 1985, p. 36-37.) However, during the war between Iran and Iraq, the religious government in Iran, comprised of divine authorities, used specific passages from the Koran to legitimize and promote self-sacrifice, or what could be called religious suicide, among the followers. The passages from the Koran read as follows: "Wars come to provide martyrs and God may prove those who believe," and "Paradise is only to be attained when God knows who will really strive and endure." No one has a history of direct contact with death and can report the experience. As Hayes (1992) has indicated, "personal death" is a verbal construction consisting of many stimulus functions based on various relations with other events. In the case of religious suicide, death is associated verbally with heaven. Heaven, by definition, cannot be directly experienced, as can houses, cars and parks. But by way of a transfer of functions through relational classes, it is possible for the word, "Heaven" to acquire stimulus functions similar to those of a garden with fountains and shade, in which believers will be entertained by beautiful metaphysical beings with "complexions like rubies and pearls" (Brooks, 1995). Hence, through derived relations with other directly experienced events, "heaven" may come to function as an effective consequence for rule following. Under these conditions, one may become a martyr, a "soldier for God," and martyrdom may be seen as a ticket to heaven. In addition, this type of verbal repertoire is further established by direct acting social contingencies (maintained by immediate social environment of family, friends, peers etc.) this sets that occasion and reinforce pro-martyrdom thoughts and associated activities (see Figure 1).

Martyrdom As a Moral or Religious Practice

One of the central issues in the analysis of religion is that of the relation between morality and religion. Schoenfeld (1993), Kantor (1981), and others have addressed the ambiguity of the relationship between these two types of action. The notion that morality is dependent on religion is widely maintained by theologians who argue for the need to return to religion; by moralists seeking to promote civic or personal virtue; by educators advocating the teaching of religion in public schools, and by politicians advocating for family and other "traditional" values.

Assuming a dependance of morality on religion does not necessarily mean that morality is logically dependent on religion. It may mean, instead, that morality is historically dependent on religion (Kantor, 1981; Schoenfeld, 1993), or that morality is psychologically dependent on religion. In this regard, Schoenfeld (1993, pp.129-134) purports that the principal distinction between moral codes and religious codes is that the latter imply greater and more rigid behavioral discipline. In comparing morality and religion, Schoenfeld argues that religion is less subject to opportunism and manipulation since it is assumed to emerge from a divine and hence unchanging source.

Based on Houmanfar, Hayes, and Fredericks (2000), an alternative interpretation is possible, however. Derivation from a divine or powerful source may make the manipulation of the opportunistic circumstances for religious practice more effective. In other words, religious practices rest on a number of ultimate metaphysical constructions which, in turn, are subject to manipulation by religious as well as social authorities. By virtue of a truth criterion of authority, the justification of religious practices is appreciably vulnerable to manipulation by self-professed religious Figures. The following examples and associated discussions are depictive of the sociological impact of leaders' opportunistic approach to martyrdom.

In an interview with a leader of Hamas, Juergensmeyer (2008) noted that the term "martyr" is used to describe someone who "diligently and reverently [gives] up their lives for the sake of their community and their religion" (p. 417). From the perspective of Islamic jihadis, they are fighting a cosmic war that clearly delineates good from evil. In this war, which transcends national boundaries, the concept of a "civilian" does not exist to a martyr. Their targets are not individuals, but rather a stereotyped "faceless collective" (p. 426) which includes ordinary citizens such as school children and housewives. It is an entire way of life that is the enemy, and anyone who participates is justifiably targeted.

In his speeches, bin Laden referred to various "satanic" acts brought on by the West including the presence of troops on the Arabian Peninsula, the Israeli-Palestinian conflict, economic sanctions imposed on Iraq after Desert Storm, and various other issues framed as evidence that the West intends to rid the entire world of Islam, including other "heretics" such as those in Saudi Arabia and other Middle Eastern countries who cooperate with the West (Steger, 2009). In conjunction with the "fourth wave" of terrorism mentioned by Flint and Radil (2009), bin Laden suggested that political power should only be exercised in the name of God, which transcends all manmade political and national boundaries.

In summary, the above examples provide a descriptive account of the relationship between martyrdom as a religious practice to cultural leaders' opportunistic decision making behaviors. Our analysis drew upon the reciprocal influence between moral and religious practices. In light of these distinctions, we believe further delineation associated with religious and non-religious practices may provide further account of geopolitical and socio-economic factors in our interdisciplinary account of martyrdom.

An Interdisciplinary Approach to the Analysis of Martyrdom

The analysis of cultural practices and their role in cultural survival has broadened the scope of behavior analysis considerably. A number of these formulations (e.g., Biglan, 1995; Glenn, 1988, 1989, 2004) have benefited from interdisciplinary contacts; significant among these have been commerce with behavioral anthropology (Harris, 1979). Others have proceeded on more specifically behavioral grounds (e.g., Hayes, 1988; Kantor, 1982; Malott, 1988; Skinner, 1972).

As mentioned by Houmanfar, Hayes, and Fredericks (2001), there is substantial support among behavior analysts that cultural practices are conditioned by social or verbal influence. Hayes (1988) accounts for the maintenance of cultural practices by reference to the complexity of other contingencies (e.g., strength of an adjustment and strength of a practice) that operate in a cultural context, as opposed to suggesting a final outcome that inevitably connects all practices. Kantor (1982) also avoids comments on final outcomes, focusing instead on a number of factors (e.g., group size, history, the characteristics of cultural stimuli) that contribute to the longevity of cultural behavior. Cultural practices that are defined as similar patterns of behaviors or operant content (usually resulting from similar environment) are transmitted inter-individually (Hayes, 1988) leading to what Glenn (2004) refers to as culture-behavioral lineage. As addressed by Hayes (1988), the strength of an individual adjustment is measured by its longevity and probability within the individual's repertoire; while the strength of a cultural practice is measured by its prevalence in a group. Furthermore, cultural practices are strengthened and transmitted interindividually while adjustments are strengthened and transmitted intraindividually. This interindividual transmission occurs through modeling, interaction with products of other individual's behavior as well as verbal interaction among individuals of a given cultural group. Leung (2003) tells the story of Murad Tawalbi, a 19 year old boy from the West Bank who was recruited by his older brother for a suicide mission. In Murad's eyes, he was already dead. As his brother strapped the bomb to Murad, his brother was overcome with joy, which gave Murad more confidence to carry out his mission. As he approached his target (a marketplace), with his finger on the detonator, he never felt so calm in all his life. Upon reaching his target, he pressed the detonator but his bomb malfunctioned and he was later arrested. Few can live to tell such a story.

Internet technology and media have played a substantial role in the rapid and to some extent uncontrollable cultural transmissions of practices in recent years. The opportunity for members of different cultures to share similar cultural environments is more available than ever before. In that regard, the geographical boundaries that once demarcated similarities of the cultural environment and hence differences across cultural groups are not as important as heretofore. For instance, one of the recent topics associated with the war on terror in western countries pertains to Middle Eastern as well as Somalia-based jihadists' use of rap music to attract western recruits (Somalia-based American, 2010, May 20). Muslim youths are increasingly using technology to express themselves, connect with others around the world, and challenge traditional power structures. Although access to technology lags in many Muslim countries due to governmental factors and restrictions on economic development, the prevalence of Muslim youth turning to technology is growing rapidly, particularly within the last five years (Tanneeru, 2009). One of the first dramatic examples demonstrating the facilitative role of technology comes from the widespread Iranian protests in 2009 that demonstrated the use of increasingly sophisticated cell phones and social networking tools such as Twitter. Youth under the age of 30 are estimated to make up 60% of the Muslim population in the Middle East. If one word differentiates them from their parents, it is "globalized." Then, at the start of 2011 the world witnessed the overthrow of governments in Tunisia and Egypt followed by widespread anti-government protests across the Middle East in what has been called the Twitter Revolution (Ghannam, 2011). Indeed, the effects of the Internet on Islam may be comparable to the effects of the printing press on Christianity in the 16th century (Tanneeru, 2009). With regard to the analysis of behavioral change in relation to changes at the cultural practice level, a discussion of the interdisciplinary contact across these levels is warranted.

Point of Contact through Science of Behavior and Science of Culture

According to the interdisciplinary contact, behavior analysis focuses on individual behavior while sociology and anthropology focus on group action. This group action or pattern can be viewed as being composed of individual behaviors. Therefore, individual behavior may be viewed as the substrate of cultural practices (Glenn, 1988). In that regard, the goal of an interdisciplinary perspective on cultural practices and entities is not reduction, but rather clarification of the relationship of phenomena across the two levels of analysis (Houmanfar et al., 2001). In that regard, we believe Glenn's (1988, 1989, 2004) work on the metacontingency and macrocontingency is a significant contribution to helping bridge the relationship between the individual and cultural levels of analysis of complex phenomena such as martyrdom.

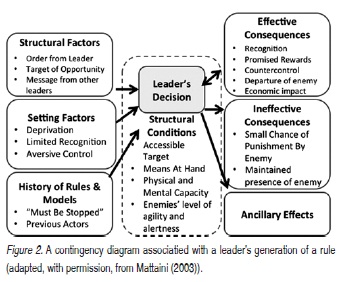

The concept of the metacontingency together with the concept of the behavioral contingency allows for the examination of the interlocking behaviors and the behavioral contingencies involved therein that contribute to an aggregate product that meets some environmental demand. According to Glenn (1988, 2004), the metacontingency is parallel to the behavioral contingency, however, they each deal with phenomena at different levels of organization. The behavioral contingency consists of an antecedent, a behavior, and a consequence. The metacontingency, on the other hand, consists of "interlocking behavioral contingencies, their aggregate product, and their receiving system" (Glenn & Malott, 2004, p. 100). The contingencies are referred to as interlocking because the behavior or the consequence of one individual's behavior functions as antecedents for another's behavior. The last component, the receiving system, may be exclusive to organizations, but may be translated to environmental or societal demand for other types of groups that may not be considered organizations. In the case of terror groups, the most likely environmental factors that affect the reoccurrence of IBCs are promised rewards, recognition and countercontrol (see Figure 2).

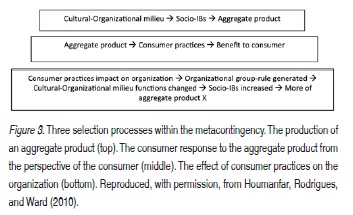

The previous examples mentioned of terror groups' activities demonstrate the participation of multiple factors in their maintenance and evolvement over time. Houmanfar, Rodrigues, and Ward's (2010) conceptualization of the metacontingency presents an elaborated articulation of antecedent and consequential factors that participate in organizational performance at various levels of analysis. In particular, these authors suggest that there are three processes of selection occurring (see Figure 3). While previous perspectives of this concept viewed it as consisting of IBCs that were selected by the receiving system (e.g., consumers), our review of the concept leads us to believe that the metacontingency involves three processes of selection. One process involves the leadership and the followers and their selection of what we call socio-IBs. This delineation of psychological and sociological levels within the metacontingency helps clarify that behavior within an organization is a function of the reinforcers, punishers, and policies that comprise the antecedent and consequences contacted by individuals. Thus, if the metacontingency is to be a selectionist construct extrapolated to the sociological level, it may be more in keeping with selectionist thinking to think of interlocked behavior, rather than interlocking behavioral contingencies as the unit of selection. Accordingly, when the selection process to the sociological level is extrapolated, via the metacontingency, it is possible to see that it is the interlocked behaviors taken as an integrated whole, rather than IBCs taken as a whole, which is the appropriate and substantively different unit of analysis at this higher level. For the remainder of the paper, we will therefore refer to interlocked behaviors (IBs) when discussing the psychological level and socio-interlocked behaviors (socio-IBs) when discussing the sociological level of analysis. While the former entails individuals' behavior embedded within the local contingencies of the organization, the latter refers to the behavior of all individuals in the organization taken as a cohesive whole. Although behavior cannot occur without physiology and organized practices cannot occur without behavior, this study considers it is important to conceive of distinct units at each level of analysis, which may then help us better understand the connections between the levels in a more comprehensive fashion.

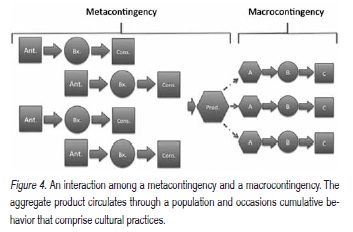

The second process involves the selection of the aggregate product by consumers (Houmanfar, Rodrigues, & Ward, 2010). It is also important to note our view of consumers as a collectivity of individuals whose behaviors and practices are not only influenced by the aggregate product but also affect the future occurrences of the aggregate product and associated socio-IBs. This delineation provides a clear connection between the influence of aggregate products on consumers' similar patterns of responding (cultural practice, see Glenn, 2004) that lead to not only the indirect selection of socio-IBs but also cumulative products or effects on the environment (e.g., viewers and advertisers of radical children's television shows, as discussed below). The latter process associated with the cumulative product is depicted by Glenn's concept of macro-contingency (Glenn, 2004; Malott & Glenn, 2004).

The third process of selection is associated with group-rules. The organizational leader or the leader of an organized group is both the generator of the group-rules as well as the follower or listener of the group-rules. The organizational leadership, therefore, is involved in the selection of both its socio-IBs and its group-rule generation. Although the group-rules and the socio-IBs are closely tied to one another in that the former typically influence the latter, their selection may occur under different conditions. In short, group-rule generation may be subject to selection by management or a board. Accordingly, the role of leaders in organizations is of importance due to their involvement in group-rule generation (Houmanfar et al., 2010).

Glenn (2004) has also introduced the concept of the macrocontingency, a unit of analysis that describes the relations between a cultural practice and the cumulative consequences arising from all those within a culture that engage in that practice. For example, continuous exposure to training material associated with Radical Islamic acts may contribute to eventual acts of martyrdom that may lead to many casualties and localized socio-economic effects (city, state or country). However, at the level of macrocontingency, the cumulative effect of many people engaging in the practice of martyrdom may result in greater casualties and economic consequences of a global magnitude (e.g., 911 attacks).

As it is possible to appreciate, most stimulus conditions which participate in development and maintenance of cultural practices are products of organizations (e.g., houses, cars, most forms of media). Conversely, organizations operate in relation to sociological conditions (e.g., consumer practices, markets, the economy, geo-political climates). Thus, understanding sociological events (political, economic, etc.) in terms of their impact at the psychological level (leadership decision making which leads to acts of martyrdom) is warranted. In that regard, we believe that product generation rely not only on selection by consumers but also on the cultural milieu which consists of the prevailing beliefs within the culture as well as predictions about the future. Similarly rules can govern behavior before that behavior comes into contact with contingencies, societal beliefs about the future - be it the economy, a richer middle-class, the competition, or other factors - can also guide the production of different goods which consumers may or may not purchase. This relationship can be circular when consumer purchases of goods will often alter the cultural milieu resulting in a different set of beliefs or predictions about which products will be successful. The growth of the internet, for example, has ramifications beyond its simple use by netizens, it has revolutionized access and sharing of information and has created a whole new online marketplace for Jihad that government leaders are forced to deal with, to name just two of its effects.

An interaction between a metacontingency, and macrocontingeny (see Figure 4) is depicted in the following example. Primary sources of training for violence and future acts of martyrdom is Hamas sponsorship of children's television shows and summer camps (metacontingencies) that indoctrinate Palestinian children (consumers) into violence or martyrdom (at the individual level with cumulative effect at the collectivity level; macrocontingency) (Blake, 2009; Christensen, 2009). The general message preached in these contexts is that jihad and martyrdom are great things and must be undertaken against the enemies of Islam (i.e., the West). Moreover, terrorist groups in general have taken advantage of the internet to radicalize youth with sophisticated films depicting the life stories of young martyrs allegedly defending Islam (Blake, 2009). Therein, what is needed are opportunities to harness that energy away from violence and into more constructive avenues tied to larger causes (e.g., making the world a better place) (Blake, 2009). One attempt to do this comes from the children's television show Sesame Street. In response to Hamas-sponsored children's TV shows advocating for violence, Sesame Street developed a show specifically for the Palestinian territories in which their Muppet characters teach nonviolence, tolerance, and understanding in children in an attempt to channel their energy in more positive directions (Christensen, 2009).

The third process of selection is the selection of effective group-rules by the leaders in the organization (Houmanfar, Rodrigues, & Ward, 2010). The organizational leadership is both the generator of the group-rules as well as the follower or listener of the group-rules. The leadership, therefore, is involved in the selection of both its socio-IBs and its group-rule generation. Although the group-rules and the socio-IBs are closely tied to one another in that the former typically influence the latter, their selection may occur under different conditions. Group-rule generation may be subject to selection by the leader. Our examples associated with the group-rule component of the metacontingency were presented earlier in sections on interactions between moral and religious practices plus religious and non-religious practices. Figure 2 shows the factors affecting leader decisions and the effects of their contingency manipulation on the interlocked behaviors of their followers. However, indirect-acting contingencies also affect leader behavior (e.g., enemy's withdrawal from their territory or damaging enemy's economy) In their role as guides to terror groups' actions, leaders generate new verbal relations between the current and future state of the enemy's circumstances as well as martyrs' after-life rewards.

Leaders have to take into consideration the ever-evolving external political and economic environment and verbally evaluate the potential adaptations the organization can make to those possible futures. These relations are based on an imagined, verbally constructed future that, for the leader at least, bears some sensible connection with the current situation. However, these relations ought not to make sense just for the leader, but also for the rest of the people in the organization if they are to behave in accordance with said relations. For, it is not just leaders, but also their followers who are engaged in producing coherent relational networks and any new directions from leadership must comport with their group members views of things (Houmanfar, Rodrigues & Smith, 2009). The role of leaders, therefore, is of importance due to their involvement in group-rule generation and control over contingencies associated with governance of many individuals behaviors. In short, it is believed that the psychological level of analysis and associated interventions at this level set the occasion for sociological impact at the socio-IBs and eventually macrocontingeny level through mediating effect of aggregate product.

Moreover, the current political and economic across the work are more interlocked than ever before. So, the above metacontingeny and macrocontingency interrelationship is also depictive of ways by leadership practices across government, public and private organizations in economically powerful countries impact counter terror activities of their consumers and citizens. In short, we believe that for our behavioral scientific interventions (as the psychological level) to demonstrate most effective social impact, we need to target behavioral change at the leadership level (Biglan 2009).

Today, terror groups may be evolving in two divergent directions: (a) increased bureaucratization and, (b) leaderless jihad. The concept of metacontingency offers a systematic view of both groups' actions in relation to their geo-political environments. The former is characterized by increased isomorphism, or similarities in organizational processes across groups based on their success in contributing to the functioning of the group. The primary advantage of isomorphism, seen in groups such as Hamas and Al-Qaida, involves improved logistical capabilities regarding relatively complex tasks such as the coordination of the 9/11 attacks on the U.S. (Helfstein, 2009; also see Alavosius, Houmanfar, & Rodrigues, 2005). Regarding counterterrorism efforts, the improved logistics of isomorphic groups can impede efforts, but the similarities in the practices of these groups can ease the degree to which counterterrorism agencies can detect terror groups. Lastly, effective counterterrorism efforts can be highly generalizable since these groups tend to adopt similar practices (Helfstein, 2009).

From a behavior analytic perspective, isomorphism may be characterized in terms of increased component complexity and hierarchical complexity (Glenn & Malott, 2004). Where the former entails increased numbers of organizational elements or processes, the latter specifically entails increased numbers of subsystems or management levels. The interplay between isomorphic terror groups like those of Al Qaida and government counterterrorism groups is understandable in terms of interactions among various elements that comprise two broad types of metacontingencies, one type being the metacontingency comprising Al Qaida as an organization and the other comprising any given counterterrorism organization. At times the aggregate products of both organizations may interact. For example an aggregate product of a counterterrorism organization may take the form of raids on terror operations in their final stages of preparation for an attack (the latter constituting an aggregate product of a terror group). Other times, such raids may focus on terror operations that participate in IBs more distally connected to attacks such as training camps and methods of financing.

Leaderless jihad, by contrast, is characterized by autonomy and considered to be a new and particularly dangerous development since the War on Terror began in 2001 (Helfstein, 2009). The lean organizational structure of these groups increases their stealth and presents a significantly greater obstacle to identification by counterterrorism agencies than do isomorphic groups. Autonomous groups are better than isopmorphic groups in solving problems arising in simple operations, whereas isomorphic groups' can more effectively handle complex tasks. The recent evolution of this leaderless jihad movement,, whose members receive relatively little training but are dedicated to terrorist causes, has been facilitated by information technology such as the internet (Helfstein, 2009).

One can make the case that leaderless jihad groups are the inverse of isomorphic groups. Thus, from a behavior analytic perspective, the former tend to be characterized by decreased component and hierarchical complexity (Glenn & Malott, 2004). As noted by Alavosius, Houmanfar, and Rodrigues (2005), the predominant "lateral" rather than hierarchical organizational structure can be facilitative of increased adaptability to unforeseen circumstances, particularly in terms of the organization of communication networks and subsequent information sharing. These processes may be the key factors that decrease their detectability by counterterrorism agencies, as mentioned previously.

The leaderless jihad movement as a whole may be interpreted in terms of relations between meta- and macrocontingencies. A macrocontingency describes a relation between cumulative, non-interlocking, entities and a cumulative effect . The non-interlocking entities may include the cumulative behavior of individuals, such as the cumulative smoking behavior of many individuals resulting in cumulative health outcomes, but may also include the cumulative IBs of groups, such as the cumulative organizational practices of factories tied to cumulative pollution levels (see Glenn, 2004, p. 150).

As mentioned previously, the leaderless jihad movement has been facilitated by the Internet, which puts individuals in contact with various aggregate products of isomorphic groups such as Al Qaida. For example, one group of known Al Qaida products pertain to videos of Osama bin Laden preaching the ideology of radical Islam. In todays world, many aggregate products take the form of information whose access is free of traditional constraints related to space and time. Most importantly, such products can be electronically copied and disseminated instantaneously around the world with ease. In this case, the aggregate products of an isomorphic group become the primary stimuli that participate in the cumulative behavior and cumulative group phenomena that characterize the leaderless jihad movement as a whole. The primary cumulative effect of interest resulting from the movement likely concerns the number and success of attacks resulting from these groups.

Conclusion

This paper provided a descriptive analysis of the geopolitical, socio-economic and historical conditions that generate religious practices associated with martyrdom. In that regard, by placing an emphasis on suicide bombings and their relation to religious practices, we offered a brief history of the evolution of martyrdom. Additionally, we discussed the relation of such religious practices to cultural leaders' opportunistic decision making behaviors. Our analysis drew upon distinctions between religious and non-religious, plus religious and moral practices. In light of these distinctions, we addressed the significance of the reciprocal relationship between psychological and sociological levels of analysis. By delineating the relationship across psychological and sociological levels of analysis, we discussed ways by which the influences of political leadership at the psychological level make the manipulation of the opportunistic circumstances for cultural practices (pro or against terror) more effective at the sociological level. In short, we believe that further empirical analyses associated with precise specification and demonstration of the means by which leadership level interventions influence our analysis of cultural change is a challenge that is worth the direct attention of behavior analysts- engineers of human behavior.

References

Alavosius, M., Houmanfar, R., & Rodrigues, N. J. (2005). Unity of purpose/Unity of effort: Private-sector preparedness in times of terror. Disaster Prevention and Management, 14, 1-15. [ Links ]

Atran, S. (2006). The moral logic and growth of suicide terrorism. The Washington Quarterly, 29, 127-147. [ Links ]

Biglan, A. (2009). Increasing psychological flexibility to influence cultural evolution. Behavior and Social Issues, 18, 1-10. [ Links ]

Blake, J. (2009, August 13). Experts: Many young Muslim terrorists spurred by humiliation. Retrieved May 11, 2010 from http://edition.cnn.com/2009/WORLD/meast/08/13/generation.islam.violence/index.html. [ Links ]

Brooks, G. (1995). Nine parts of desire. New York: Anchor Brooks, Doubleday. [ Links ]

Christensen, J. (2009, August 13). Reaching the next generation with 'muppet diplomacy.' Retrieved May 11, 2010 from http://edition.cnn.com/2009/WORLD/meast/08/13/generation.islam.gaza.muppets/index.html. [ Links ]

Flint, C., & Radil, S. M. (2009). Terrorism and Counter-Terrorism: Situating al-Qaeda and the global war on terror within geopolitical trends and structures. Eurasian Geography and Economics, 50, 150-171. [ Links ]

Ghannam, J. (2011, February 18). In the Middle East, this is not a Facebook revolution. The Washington Post. Retrieved February 18, 2011 from http://www.washingtonpost.com/wpdyn/content/article/2011/02/18/AR2011021802935.html. [ Links ]

Glenn, S. S. (1988). Contingencies and metacontingencies: Toward a synthesis of behavior analysis and cultural materialism. The Behavior Analyst, 11, 161-179. [ Links ]

Glenn, S. S. (1989). Verbal behavior and cultural practices. Behavior Analysis and Social Action, 7, 10-15. [ Links ]

Glenn, S. S. (2004). Individual behavior, culture, and social change. The Behavior Analyst, 27, 133-151. [ Links ]

Glenn, S. S., & Malott, M. E. (2004). Complexity and selection: Implications for organizational change. Behavior and Social Issues, 13, 89-106. [ Links ]

Harris, M. H. (1979). Cultural materialism. New York: Random House. [ Links ]

Hayes, S. C. (1988). Contextualism and the next wave of behavioral psychology, Behavior Analysis, 23, 7-23. [ Links ]

Hayes, S. C. (1992). Understanding verbal relations. Reno, NV: Context Press. [ Links ]

Helfstein, S. (2009). Governance of terror: New institutionalism and the evolution of terrorist organizations. Public Administration Review, 69, 727-739. [ Links ]

Houmanfar, R., Hayes, L. J., & Fredericks, D. W. (2001). Religion and cultural survival. The Psychological Record, 51, 19-37. [ Links ]

Houmanfar, R., Rodrigues, N. J., & Ward, T. A. (2010). Emergence & metacontingency: Points of contact and departure. Behavior and Social Issues, 19, 53-78. [ Links ]

Houmanfar, R., Rodrigues, N. J. & Smith, G. S. (2009). Role of communication networks in behavioral systems analysis. Journal of Organizational Behavior Management, 29, 257-275. [ Links ]

Juergensmeyer, M. (2008). Martyrdom and sacrifice in a time of terror. Social Research, 75, 417-434. [ Links ]

Kantor, J. R. (1981). Interbehavioral philosophy. Chicago, IL: Principia Press. [ Links ]

Kantor, J. R. (1982). Cultural psychology. Chicago, IL: Principia Press. [ Links ]

Leung, R. (2003, March 25). Mind of a suicide bomber. Retrieved May 11, 2010 from http://www.cbsnews/stories/2003/05/23/60minutes/main555344.shtml. [ Links ]

Malott, R. W. (1988). Rule-governed behavior and behavioral anthropology. The Behavior analyst, 11, 181-203. [ Links ]

Martyr. (2010). Retrieved April 15, 2010 from http://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/martyr. [ Links ]

Mattaini, M. A. (2003). Understanding and reducing collective violence. Behavior and Social Issues, 12, 90-108. [ Links ]

Piazza, J. A. (2009). Is Islamist terrorism more dangerous? An empirical study of group ideology, organization, and goal structure. Terrorism and Political Violence, 21, 62-88. [ Links ]

Preti, A. (2006). Suicide to harass others: Clues from mythology to understanding suicide bombing attacks. Crisis, 27, 22-30. [ Links ]

RAND Database of Worldwide Terrorism Incidents. Retrieved May 18, 2010 from http://www.rand.org/nsrd/projects/terrorism-incidents.html. [ Links ]

Schoenfeld, W. N. (1993). Religion and human behavior. Boston, MA: Authors Cooperative. [ Links ]

Sidman, M. (2003). Terrorism as behavior. Behavior and Social Issues, 12, 83-89. [ Links ]

Skinner, B. F. (1972). Beyond freedom and dignity. New York: Knopf. [ Links ]

Somalia-based American jihadist using rap music to attract western recruits (2010, May 20). Retrieved May 20, 2010 from http://news.oneindia.in/2010/05/20/somaliabased-american-jihadist-using-rap-music-toatt.html. [ Links ]

Steger, M. B. (2009). Religion and ideology in the global age: Analyzing al Qaeda's Islamist globalism. New Political Science, 31, 529-541. [ Links ]

Tanneeru, M. (2009, August 7). Young Muslims turn to technology to connect, challenge traditions. Retrieved May 11, 2010 from http://edition.cnn.com/2009/WORLD/meast/08/07/generation.islam.tech/index.html. [ Links ]

Wright, R. (1985). Sacred rage. New York: Linden Press/ Simon & Schuster. [ Links ]