Serviços Personalizados

Journal

Artigo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Acessos

Acessos

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares em

SciELO

Similares em

SciELO -

Similares em Google

Similares em Google

Compartilhar

Revista Latinoamericana de Psicología

versão impressa ISSN 0120-0534

rev.latinoam.psicol. vol.45 no.2 Bogotá maio/ago. 2013

Price anchoring in Online Markets: an Empirical Assessment

Anclaje de Precio en las compras online: un análisis empírico

Francesco Bogliacino,

Fundación Universitaria Konrad Lorenz, Colombia

Alexander Cuntz

Joint Research Center - European Commission, Institute of Prospective

Technological Studies, España.

Berlin University of Technology, Alemania

Francesco Bogliacino. Corresponding Author. Fundación Universitaria Konrad Lorenz, Carrera 9Bis, No 62-43, Bogotá, Colombia, email: francesco.bogliacino@gmail.com, Tel: (+57) -1-3472311 ext. 162.

Alexander Cuntz. Joint Research Center European Commission Institute of Prospective Technological Studies, C/ Inca Garcilaso, 3, 41092 Seville, Spain. Berlin University of Technology, Chair of Innovation Economics, VWS 2, Müller-Breslau-Strasse, 10623 Berlin, Germany

The views expressed are purely those of the author and may not in any circumstances be regarded as stating an oficial position of the European Commission.

Recibido: Mayo de 2013 Revisado: Junio de 2013 Aceptado: Julio de 2013

Abstract

There is a large literature in behavioral economics contradicting the empirical prediction of rational choice theory once applied to auctions. The issue is of particular relevance due to the large use of auctions in mechanism design. One of the heuristics that may induce biased behavior is anchoring, namely the possibility that uninformative information influences choices. In this article we assess the impact of the anchoring effect in bidding for online auctions. Our aim is to isolate the anchoring effect of fixed price listing from the strategic bidding effect. Our empirical strategy is to use market segmentation induced by the presence of counterfeit products. Our results confirm the importance of behavioral heuristics and associate biases in auction. In particular we find price effects on auctions from upper and lower bounds(ceiling and foor) of the fixed price distribution and across run time. The results are robust with regard to various formulations of the baseline regression.

Key words: auction; anchoring; counterfeit, heuristics.

Resumen

Hay una amplia literatura que contradice las predicciones empíricas de la teoría de la elección racional aplicada a las subastas. El asunto es de mucha relevancia puesto que las subastas son muy utilizadas en el diseño de mecanismos. Uno de los heurísticos que puede introducir sesgos en los comportamientos es el anclaje, o sea la posibilidad que información irrelevante tenga influencia en la elección. En este artículo medimos el impacto del anclaje en las pujas de las subastas en línea. Nuestra estrategia empírica consiste en utilizar la segmentación del mercado inducida por la presencia de productos falsos. Nuestros resultados confirman la importancia de los heurísticos y los sesgos en las subastas. En particular, encontramos efectos de precios en las subastas desde los límites máximos y mínimos de las distribuciones de los precios fijos y a través del tiempo de ejecución. Los resultados son robustos a varias formulaciones de la regresión básica.

Palabras clave: subastas, anclaje, falsificación, heurísticos.

The theoretical literature on auctions is based on rational choice (Milgrom, 2004), as specified by the assumptions underlying the Expected Utility (EU) hypothesis. The Axiomatic foundation of EU is presented in Von Neumann and Morgenstern (1944) and critically discussed in Camerer and Loewenstein (2003). In particular, given the presence of uncertainty, the basic predictions for the auction come from the application of the game theoretic concept of sequential equilibrium, where cognitive requirements by agents are in striking violation of most experimental evidence. We should also mention that even some game theorists have raised more than one objection to some of these requirements; for instance, with regard to consistency Kreps (1990, p. 430) stated that "a lot of bodies are buried in this definition". The issue of how agents behave in an auction framework goes beyond the legitimate scientific interest: given the typical "competitive" feature of auction, the latter is usually proposed as an "implementation" mechanism (Osborne & Rubinstein, 1994, chap. 11) to accomplish a target in policy setting (i.e. the so called mechanisms design, as explained in Milgrom, 2004). A relatively recent case of application has been the auction design related with the US Treasury's Rescue Plan (Ausubel & Cramton, 2008). If the participant's behavior is significantly and systematically distant from the EU prediction, and if - as discussed by Camerer and Fehr (2006) - there is no a priori guarantee that the "economic man" dominates other behaviors, then the theory's predictive capability can be seriously harmed and its application to the policy contest may lead to unattended consequences.

There is now ample literature falsifying the EU hypothesis (Camerer & Loewenstein, 2003; Kahneman & Thaler, 2006). There are a couple of empirical anomalies that we recall here because of the relevance for our discussion.

-

The hypothesis that the probability judgment follows the axiom of Bayesian statistics is systematically contradicted. The experimental evidence suggests that subjects tend to use heuristics, i.e. rule of behaviors, which allows them to prevent their computational and cognitive limitations. This type of heuristics is associated with biases, i.e. violation of basic statistical rules or of logic, which are due to the error of approximation occurring while using predefined rules (Tversky & Kahneman, 1974).

-

Moreover, experimental evidence suggests that preferences do not represent a predefined ordering, from which the subject selects their best option given the constraints: as discussed by Kahneman and Tversky (1979) and Tversky and Kahneman (1991), ranking is reference dependent, i.e. it tends to be influenced by the framing of the situation like presence of a status quo or default options etc. (Tversky & Kahneman, 1986) and is "constructed" in relation to the specific choice setup (Slovic, 1995).

However, in the domain of auctions, standard theory states that personal valuation of the good is known ex ante by each participant, probability judgment is consistent with Bayesian rules, and, as a result, the bid is the result of strategic thinking. As shown by Jones (2011) using data from eBay auctions of Amazon.com gift certificates, there is evidence supporting the hypothesis of "bidding fever" (see also Thaler, 1988), and bidding is often subject to anchoring (for other experimental evidence which contradicts the prediction of the main theorems, see Lucking- Reiley, 1999).

As explained in Chapman and Johnson (2002), anchoring has been defined as an anchoring procedure of suggesting a salient uninformative number to subjects, an experimental evidence that uninformative information influences results or, finally, a psychological process through which unrelated information affects decision-making. Since we are estimating anchoring effects from non-experimental settings, where we cannot control all the surrounding variables, we end up measuring a reduced form effect; as a result, the interpretation of anchoring we will adhere to is that of the second definition, notwithstanding the nature of the data used. Anchoring lies -Chapman and Johnson (2002) argue- in the activation phase: since the anchor is considered as a candidate response, information related with the anchor is retrieved and used in the target estimation phase.

If anchoring occurs in auctions, then it may be a concern for policymakers: the use of uninformative information may be strategically exploited by sellers in order to generate overbidding. An empirical investigation is necessary since there is large evidence that consumers are not fully empowered (Eurobarometer, 2011; European-Commission, 2011) and because debiasing can occur (Chapman & Johnson, 2002). In fact, policymakers will be given the possibility to both regulate online auction settings to avoid the exploitation of anchoring effects and/or design proper debiasing.

Within the context of online auctioning, a bidder is usually given the opportunity to withdraw from the auction and buy at a specified price. There is evidence that evaluations are influenced by "fixed price" alternatives (Dodonova & Khoroshilov, 2004), but this explanation is observationally equivalent to a pure strategic effect: in fact, according to standard theory, the fixed price alternative plays the role of an outside option and provides information, which should be rationally considered in optimal bidding (Malmendier & Lee, 2011). In fact, higher-valued outside options theoretically lead to less aggressive bidding than in auction models without outside options. Bidders exploit outside options by decreasing bids up to the outside option value (valuation net of transaction costs). However, empirical evidence is challenging also in this matter: the revenue equivalence theorem also applies to the case of outside options, i.e. the expected revenue for a first-price auction equals that for a second-price auction, but laboratory evidence documents that the first-price auction generates larger revenue than the second-price auction, with and without outside option (Cox, Robertson, & Smith, 1982; Kirchkamp, Poen, & Reiss, 2009). For those who are not familiar, the difference between the first price and second price auction is the following: in a first-price auction, bidders independently submit a single (sealed) bid, without seeing the others' bids. There is no open, dynamic bidding. The bidder who submits the highest bid wins and pays a price equal to his/her bid. In a second-price auction, once again the bidder who submits the highest bid wins, but here he/ she pays a price equal to the second highest bid (Ockenfels et al., 2006). More specifically, these differences - i.e. the revenue-premium - increase once outside options are introduced but only in first-price auctions. This is because overbidding in first-price auctions is more prominent with outside options than without. However, the amount of overbidding remains unchanged in second-price auctions such as eBay's.

Whether this outside option price is informative or not is then key to understand if anchoring occurs or not.

In this paper, we propose an identification strategy to isolate the effect of anchoring from strategic bidding, namely through the use of counterfeit. Authentic and counterfeit goods are different, clearly separated segments of the market. As a result while the effect of fixed price options on auction price within the same segment is observationally equivalent to a strategic effect, a similar effect across segments can be assigned only to anchoring and not to strategic effects. In fact, the outside option cannot be meaningful across segments (the two objects are not substitutable and the price of the other is uninformative).

Our work is strictly connected with the issue of identifying behavioral heuristics in auctions, markets and other institutional settings. An assessment of anchoring effects is in Beggs and Graddy (2009) and Dodonova and Khoroshilov (2004), bidding fever has been documented by Jones (2011) and Taler (1988), and the relevance of cognitive costs has been investigated by List and Lucking-Reiley (2002). Railey (2006) presents some evidence on the role of reserve price, more in accordance with rational choice theory. The use of market price as reference point in a price negotiation is documented experimentally in Cristensen and Garling (1997).

The data we use come from an internet auction platform. Some reviews of the empirical literature applied to this environment can be found in Ockenfels et al. (2006) and Hasker and Sickles (2010). A more general review of previous literature regarding field experiments and empirical work on auctions is presented by Lucking-Reiley et al. (2007).

The technological and economic effect of piracy counterfeit and frauds on online auctions is subject of an increasing number of contributions. Most of the strategic implications of entry by counterfeit is on the supply side of the market (Berger et al., 2012; Qian, 2008, 2010), thus further supporting our identification strategy.

In this contribution we use the information on fixed price options for auction to isolate the effect of anchoring. We use the minimum and maximum fixed price options, which are associated empirically with the two segments of authentic and counterfeit goods and, we regress them separately on counterfeit and authentic goods auction prices. We identify anchoring from strategic behavior through the cross-segments influence (maximum on counterfeit and minimum on authentic).

We find robust evidence of price anchoring in the counterfeit segment; we also find anchoring effects for the authentic once proper control for price variance is introduced.

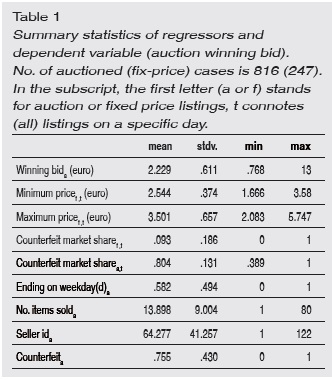

Data

Data collection for the study applies a non-participatory, observational approach using an "automated sampling technique" (Anderson, Friedman, Milam, & Singh 2004) on eBay's German auction platform, i.e. collection of involuntary survey data without influencing the participant's behavior. The data gathered on eBay tracks item listings (during actual run time) of a homogeneous, health care consumer product, starting October 1st, and ending November, 30th 2008. In addition, we focused our analysis on completed auctions and fixed-price listings. The specific, oral care product is a toothbrush head and is of no collectable value to buyers. It can be considered a low-price, common value good that has no product substitute elsewhere in online or offine markets i.e. there is a monopoly producer of the authentic product. Table 1 gives summary statistics on the dataset.

Summary statistics of regressors and dependent variable (auction winning bid). No. of auctioned (fix-price) cases is 816 (247). In the subscript, the first letter (a or f ) stands for auction or fixed price listings, t connotes (all) listings on a specific day.

Sellers and buyers can match to different market mechanisms available online, i.e. auctions or fixed-price sales. The minimum start price on eBay's auctions is 1 euro. The first bid must be at least the starting price and additional bidders have to increase the current bit with a minimum (or increment) of fifty cents. The minimum bid will be publicly disclosed by the seller and corresponds to the public reserve price in auction theory (Ockenfels et al., 2006). Every bid entered is a maximum bid to the proxy agent. eBay's proxy agent bids automatically on behalf of the bidder and increases the bid in case there are competing bids submitted by other bidders. The participant of the auction is outbid if another participant places a higher bid (eBay Inc., 2011). The best way to understand the mechanisms is through an example we draw from the online user manual. Imagine the current bid for an item listed is 5. Bidder A is this high bidder, and has placed a maximum bid of 7 on the item. Her maximum bid is kept confidential from all other bidders. Next, bidder B views the item and decides to enter the auction by placing a maximum bid of 10. In turn, he becomes the new high bidder. eBay's proxy agent automatically increments bidder A's bid to her maximum of 7, and bidder B's to 7.50. Bidder A then receives an e-mail that she has been outbid. If she doesn't raise her maximum bid before the auction ends, bidder B wins the item.

Multiple bidding on simultaneous eBay listings is allowed and it is a common practice. An alternative selling format is fixed price offers, i.e. "pure" Buy-It-Now listings. Typically, such listings are integrated into shops on eBay and might offer other special features, such as service hotlines. In addition, many of the fixed-price offers are issued by professional sellers oftentimes having longer-term membership and an explicit business profile. The latter status requires disclosure of additional personal details but, at the same time, allows for longer duration of listings, e.g. auction durations of up to 6 months. Under any selling format, by packaging items, sellers may choose to offer purchase of more than one item in a single listing.

Information on counterfeits is provided by a consultancy that is commissioned by the authentic good producer and specialized on monitoring and on security issues in online sales. The regular examination process of the consultancy requires each listing to be opened manually and inspected carefully (e.g. description, pictures, seller, sales record etc.). This detection strategy is complemented by the use of random test purchases. These samples are sent to laboratories in order to confirm or rule out counterfeit rating. Upon confirmation, all further auctions or fixed-price offers are removed according to eBay's VeRO programme. As a result the "counterfeit" status is exogenous to the price. In our dataset it is captured by a dummy.

The dependent variable we use in the estimation is the size of the winning bid in a specific auction listing. Maximum (minimum) prices at time t connote the highest (lowest) price offer among all daily buy-it-now listings at time t. Similarly, counterfeit market shares are calculated on the basis of daily auction listing at time t (or, fix-price offers on that specific day, respectively). Furthermore, our data assigns the number of sold items per listed auction, if the auction ends on a weekday, and if a specific seller runs one or multiple auctions (id).

Method

As pointed out in Section 1, our identification strategy is based on market separation between authentic and counterfeit goods. Empirically, we use the minimum price of fixed price market and maximum price (on the same day) as proxy for anchors. If the segments are effectively separated, then the two refer respectively to counterfeit and authentic goods. In order to assess the role of an anchor, we use them as explanatory variables in a regression for auction prices (using a set of control variables) separately for counterfeits and authentic goods. We call between-segment effect the effect of minimum price on authentic and maximum price on counterfeit and the within segment effects those of the minimum on counterfeit and maximum on authentic. The between segments effect is an anchoring effect, as it cannot be ascribed to strategic behavior, in that we could not find any plausible confounding factor, while the within segment can be both anchoring and strategic behavior. As a result, the latter cannot be identified, but we control it in order to avoid omitted variable bias.

In other words, if the two markets are vertically separated, the price signal coming from the outside option is informative only inside the segment: since it refers to a different, non-substitutable good, it is not meaningful outside of its own market. However, psychologically it may be recollected and used in the context in which a number is exploited as a starting point for the bidding strategy and then (usually insufficiently) adjusted. Within the segment, the outside option can act both as strategic valuable information and anchoring, thus the latter effect is not identifiable; between segments we are not aware of any other confounding factors and we think it is robust to interpret it as anchoring.

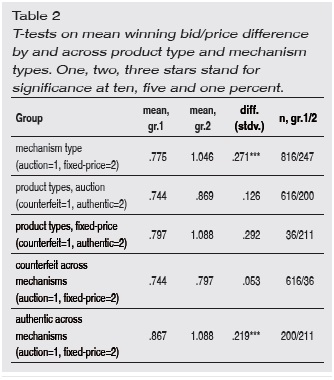

Since determination of the counterfeit status is exogenous to price, a statistical test of the separation can be carried out though a simple mean comparison, controlling for unequal variances of the two distributions of prices. As shown in Table 2, counterfeits sell of at significantly lower levels than authentic products. This happens under the auction mechanism as well as the fixed-price one. In addition, we run a number of t-tests in order to further illustrate the price characteristics of the data related to product type and the sales and cross-mechanism (see Table 2). Firstly, we find that mean prices are significantly higher in fixed-price sales than in auction counterpart sales. Lastly, cross-mechanism comparison of prices yields significant differences in mean prices of authentic products. In contrast, counterfeit prices are not significantly different across mechanisms. Moreover, as discussed above the good is a homogeneous one of no particular value, which means that differentiation is clearly associated with a different quality.

In order to estimate the effect, we run regression separating the samples into the auctions for counterfeit goods and the one for authentic goods: technically, we estimate one regression with differentiated coefficients for the two groups. Albeit the estimates are identical to those obtained by separating the two samples, it is more efficient in finite samples.

In order to control for inertial effects and the possibility that anchoring occurs in different moments during the time span in which the auction is open, we control for lagged prices up to the third day before closure (i.e. the average duration of an auction in the sample).

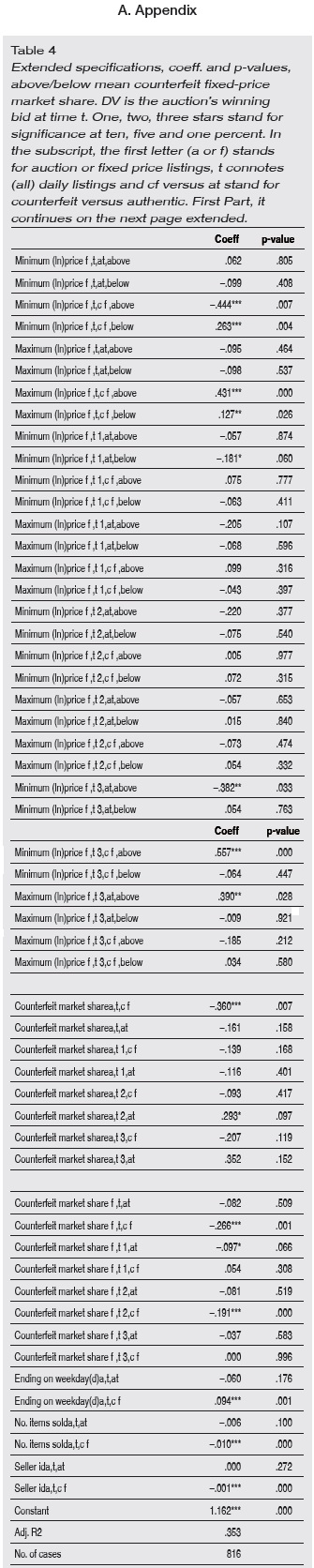

In the Appendix we also differentiate the coefficients separating between the days in which the share of counterfeits is above the average and those on which it is below. When the share of the authentic segment is below the average, price differences between counterfeit and authentic increases and the between segment effect is more likely to be pure anchoring.

Results

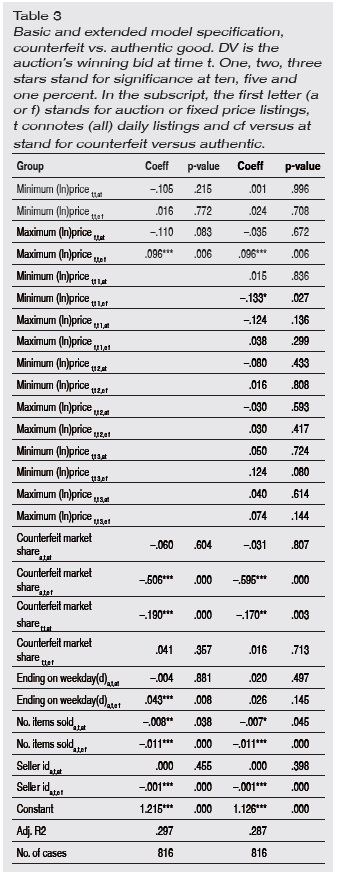

eBay's auction and fixed-price listings are highly related online markets. Prices in fixed price listings account for a substantial share of auction outcomes. In particular, we find significant price effects on auctions from upper and lower bounds (ceiling and floor) of the (fixed) price distribution and across time.

More specifically, on the one hand, counterfeit auction outcomes are negatively inclined to daily fixed price minima at time t-1 (Table 3). Goods offered in fixed price and auction markets are close to being perfect substitutes. Thus, a price increase in one market should lead to increased prices in the other as buyers will migrate to the outside option. However, we do not observe any price effects upon authentic goods. On the other hand, ending counterfeit auctions are positively inclined to daily fixed price maxima on the day the auction ends. Again, we do not observe this effect for authentic counterparts.

While the minimum fixed price effect on the closing price of a counterfeit auction can be associated both to anchoring and strategic behavior, the maximum price effect is clearly across segments, and can thus be associated with price anchoring.

Further analysis accounts for differences in daily counterfeit shares and, hence, price variance in markets that host anchors as highlighted in Table 4 in the Appendix. depending on pooling or separating fixed prices we now segregate and review the above price effects. These estimates add three important pieces of evidence.

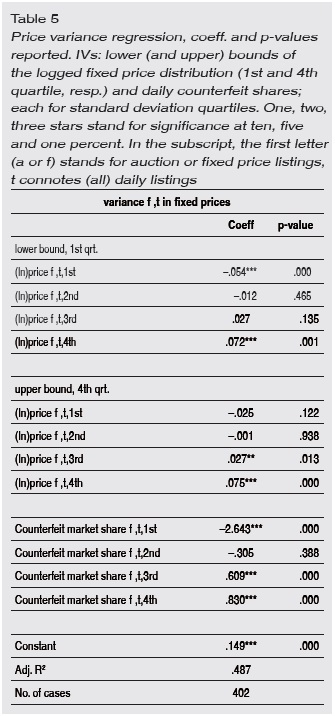

Firstly, we find that signs from price minima effects on counterfeit auctions change with increases of fixed price variance at time t. Even though within segments, arguably, here this also supports the idea of (cognitive) anchoring as it cannot really be explained by rational bidding behavior or the outside option. It replicates an anomaly present in fixed price markets which is based on the non-monotone relationship of price minima to price variance. Regression in Table 5 in the Appendix illustrates this relationship between price and counterfeit levels and price variance. Increases in minima are negatively (positively) correlated with 1st (4th) quartile variance while maxima are always positively inclined. Interestingly, increasing counterfeit shares either have positive or negative association.

Secondly, counterfeit auctions continue to be positively inclined to price maxima, independent of fixed price variance. Anyhow, effect size differs which, again, echoes monotone increases in maxima with variance, likely due to authentic seller's price signaling when fixed-price markets separate.

Lastly, we also find evidence of anchoring for authentic good auctions on prices at time t-1 and t-3. Indeed, this effect of minima on auctions for authentic goods is clearly between segmentss. In contrast, all remaining significant price effects arguably measure strategic bidding, i.e. buyer migration from fixed-price markets to auctions, but within segments.

In all model specifications we control for a number of additional factors that influence auction outcomes that we turn to now.

Basic and extended model specification, counterfeit vs. authentic good. DV is the auction's winning bid at time t. One, two, three stars stand for significance at ten, five and one percent. In the subscript, the first letter (a or f ) stands for auction or fixed price listings, t connotes (all) daily listings and cf versus at stand for counterfeit versus authentic.

In general, the willingness to pay depends on average quality of goods listed in auctions (Akerlof, 1970). Correspondingly, an increasing auction's counterfeit share reduces average bidding outcomes, in particular for counterfeited goods. More specifically, bidders with a higher willingness to pay and intention to buy authentic goods may migrate to fixed price markets with high price variance. Given counterfeit shares in fixed prices increase, authentic sellers strategically charge higher prices for their good as price signals pay off (Qian, 2010). In contrast to auctions, this provides potential buyers with additional information on type and lower risk of mismatch associated with purchase. However, in turn, migration decreases demand on auctioned items (authentic goods or counterfeit goods perceived as authentic) and, hence, leads to lower auction outcomes. This is con- firmed by significant, negative price effects.

Lastly, sellers of counterfeit products achieve higher prices when auctions end on weekdays. This is true for most specifications and is arguably due to less time dedicated to individual listing inspection by bidders than on weekends. Counterfeit sellers with a number of listings and, hence, higher risk of being detected and persecuted may not attempt to deceive bidders by their listings but wish to sell of fast and at lower prices. Similarly, bundling or packaging a number of items in a single listing significantly reduces per-item auction outcome. This price effect is more pronounced and frequent for counterfeit sales than for their authentic counterparts.

Discussion

We largely succeed in separating anchoring effects from rational bidding in auctions. Nonetheless, a more refined analysis of micro-bidding behavior in the presence of counterfeits would be desirable for future research. Data available to us is not detailed enough so as to study anchoring of individual bids and relative distance of fixed price to auction listings on user screens (Malmendier & Lee, 2011). Ideally, this would allow for research on how the auction mechanism may systematically select anchoring bids and bidders as auction winners. In addition, we are not able to control for bidder characteristics, e.g., the experience level on eBay or average time spent on inspection and decision-making with regard to bidding. However, Malmendier and Lee (2011) do not find any empirical evidence on the role of bidder experience for overbidding patterns, which is to a certain degree related to price effects from anchoring on upper bound highlighted by this study.

In general, price separation is likely to increase market efficiency and consumer welfare on eBay's fixed price market in the presence of counterfeits. On the one hand, price signals enhance buyers to identify authentic (high-quality) listings and overcome information asymmetry. On the other hand, we find that prices of lower-quality counterfeits further decrease when prices separate. Both aspects are in line with theory and evidence on price effects ex post counterfeit entry in work by Qian (Qian, 2008, 2010). Anyhow, it should be noted that, from her theoretical viewpoint, price signaling may lead to excessive, authentic good prices above monopoly ones associated with a given quality.

However, once we consider auctions on eBay consumer welfare and market efficiency in the presence of counterfeits also depends on bidder's anchoring.

Here, our analysis (table 4) identifies assimilative anchoring on upper bound and contrastive anchoring on lower bound (Ku et al., 2006) in our dataset, i.e. anchors having a positive or negative between segment effect on winning bids. Assimilative anchoring in counterfeit auctions likely echoes fixed-price signals and, thus, increases winning bids for low-quality counterfeits. Bidders on authentic auctions experience contrastive anchors which provide consumers with high quality at lower cost. Hence, the latter (the former) increases (reduces) consumer welfare. Comparing size of these effects implies a weak surplus decrease when fixed prices separate, and a weak increase when fixed prices pool. In sum, however, given the distribution of product types in auctions, the welfare decline associated with anchoring in counterfeit auctions clearly overcompensates welfare increases associated with contrastive anchoring of authentic good auctions. Consequently, anchoring in the presence of counterfeits reduces overall bidders' surplus in auctions.

References

Akerlof, G., (1970). The market for "lemons": Quality uncertainty and the market mechanism. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 84(3), 488-500. [ Links ]

Anderson, S., Friedman, D., Milam, G., & Singh, N., (2004). Buy it now: A hybrid in-ternet market institution, Santa Cruz Department of Economics, Working Paper Series. [ Links ]

Ausubel, L. M., & Cramton, P., (2008). Auction design critical for rescue plan. The Economists' Voice, 5(5), article 5. doi: 10.2202/1553-3832.1415. [ Links ]

Beggs, A., & Graddy, K., (2009). Anchoring effects: Evidence from art auct. American Economic Review, 99(3), 1027-1039. http://www.jstor.org/stable/25592492. [ Links ]

Berger, F., Blind, K., & Cuntz, A. (2012). Risk factors and mechanisms of technology and insignia copying - a first empirical approach. Research Policy, 41, 376-390. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.respol.2011.10.005. [ Links ]

Camerer, C., & Fehr, E., (2006). When does "economic man" dominate social behavior? Science, 311(5757), 47-52. DOI: 10.1126/science.1110600. [ Links ]

Camerer, C., & Loewenstein, G., (2003). Behavioral economics: Past, present, future. In: Camerer, C., Loewenstein, G., Rabin, M. (Eds.), Advances in Behavioural Economics (pp. 3-52). Princeton; Princeton University Press. [ Links ]

Chapman, G. B., & Johnson, E. J. (2002). Incorporating the irrelevant: Anchors in judgements of belief and value. In: Gilovich, T. , Griffin, D., Kahneman, D. (Eds.), Heuristics and Biases. The Psychology of Intuitive Judgement (pp. 120-138). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [ Links ]

Cox, J., Robertson, B., & Smith, V. L. (1982). Theory and behavior of single object auctions. Research in Experimental Economics, 2, 1-43. [ Links ]

Cristensen, H., & Garling, T. (1997). Determinants of buyers' aspiration and reservation price. Journal of Economic Psychology, 18(5), 487-503. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0167-4870(97)00020-2. [ Links ]

Dodonova, A., & Khoroshilov, Y. (2004). Anchoring and transaction utility: evidence from on-line auctions. Applied Economics Letters, 11, 307-310. DOI: 10.1080/1350485042000221571. [ Links ]

eBay Inc. (2011). All about bidding. URL http://pages.ebay.com/help/buy/aboutbidding.html. [ Links ]

Eurobarometer, (2011). Consumer empowerment, special eurobarometer, 342.Tech. rep., European Commission. [ Links ]

European-Commission, (2011). Consumer empowerment in the eu. Staf Working Document 469, European Commission. [ Links ]

Hasker, K., & Sickles, R. (2010). Ebay in the economic literature: Analysis of an auction marketplace. Review of Industrial Organization, 37, 3-42. doi 10.1007/s11151-010-9257-5. [ Links ]

Jones, M. T. (2011). Bidding fever in ebay auctions if amazon.com gift certificates. Economics Letters, 113(1), 5-7. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.econlet.2011.05.038. [ Links ]

Kahneman, D., & Thaler, R. (2006). Anomalies: Utility maximization and experienced utility. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 20(1), 226-234. http://www.jstor.org/stable/30033642. [ Links ]

Kahneman, D., & Tversky, A. (1979). Prospect theory: An analysis of decision under risk. Econometrica, 47(2), 263-292. http://www.jstor.org/stable/1914185. [ Links ]

Kirchkamp, O., Poen, E., & Reiss, J. P. (2009). Outside options: Another reason to choose the first-price auction. European Economic Review, 53(2), 153-169. doi:10.1016/j.euroecorev.2008.03.005. [ Links ]

Kreps, D. M. (1990). A Course in Microeconomic Theory. Princeton: Princeton University Press. [ Links ]

Ku, G., Galinsky, A. D., & Murnighan, J. K., (2006). Starting low but ending high: A reversal of the anchoring effect in auctions. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 90(6), 975-986. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.90.6.975 [ Links ]

List, J. A., & Lucking-Reiley, D. (2002). Bidding behavior and decision costs in field experiments. Economic Inquiry, 40(44), 611-619. doi: 10.1093/ei/40.4.611 [ Links ]

Lucking-Reiley, D., (1999). Using field experiments to test equivalence between auction formats: Magic on the internet. American Economic Review, 89(5), 1063-1080. http://www.jstor.org/stable/117047. [ Links ]

Lucking-Reiley, D., Bryant, D., Prasad, N., & Reeves, D. (2007). Pennies from ebay: the determinants of price in online auctions. Journal of Industrial Economics, LV (2), 223-233. [ Links ]

Malmendier, U., & Lee, H. (2011). The bidder's curse. American Economic Review 101(2), 749-787. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1257/aer.101.2.749. [ Links ]

Milgrom, P. (2004). Putting Auction Theory to Work. Cambridge University Press. [ Links ]

Ockenfels, A., Reiley, D. H., Sadrieh, A., (2006). Online auctions. In: Hendershott, T. (Ed.), Economics And Information Systems (pp. 571-628). Bingsley, UK: Emerald Publishing [ Links ]

Osborne, M. J., & Rubinstein, A. (1994) A Course in Game Theory. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press. [ Links ]

Qian, Y. (2008). Impacts of entry by counterfeiters. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 123(4), 1577-1609. doi: 10.1162/qjec.2008.123.4.1577 [ Links ]

Qian, Y., (2010). Brand management and strategies against counterfeits. NBER working paper 17849. [ Links ]

Railey D. H., (2006). Field experiments on the effects of reserve prices in auctions: More magic on the internet. RAND Journal of Economics, 37(1), 195-211. doi: 10.1111/j.1756-2171.2006.tb00012.x. [ Links ]

Slovic, P, (1995). The construction of preferences. American Psychologist, 50, 364-371. [ Links ]

Thaler, R, (1988). Anomalies: The winner's curse. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 2(1), 191-202. http://www.jstor.org/stable/1942752. [ Links ]

Tversky A., & Kahneman, D. (1974). Judgement under uncertainty: Heuristics and biases. Science, 185(4157), 1124-1131. http://links.jstor.org/sici?sici=0036-8075%2819740927%293%3A185%3A4157%3C1124%3AJUUHAB%3E2.0.CO%3B2-M. [ Links ]

Tversky, A, & Kahneman, D. (1986). Rational choice and the framing of decisions. Journal of Business, 59, 251-278. http://www.jstor.org/stable/2352759. [ Links ]

Tversky, A., & Kahneman, D., (1991). Loss aversion in riskless choice: A reference dependent model. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 106, 1039-1061. doi: 10.2307/2937956. [ Links ]

Von Neumann, J., & Morgenstern, O., (1944). Theory of Games and Economic Behavior. Princeton: Princeton University Press. [ Links ]