Services on Demand

Journal

Article

Indicators

-

Cited by SciELO

Cited by SciELO -

Access statistics

Access statistics

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in

SciELO

Similars in

SciELO -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Revista Latinoamericana de Psicología

Print version ISSN 0120-0534

rev.latinoam.psicol. vol.45 no.3 Bogotá Sept./Dec. 2013

https://doi.org/10.14349/rlp.v45i3.1485

doi: 10.14349/rlp.v45i3.1485

Pro-environmental beliefs and behaviors: two levels of response to environmental social norms

Creencias y comportamientos proambientales: dos niveles de respuesta a las normas sociales ambientales

Raquel Bertoldo,

Paula Castro

Instituto Universitário de Lisboa (ISCTE-IUL), Cis-IUL, Portugal.

y Andréa Barbará S. Bousfield

Universidade Federal de Santa Catarina (UFSC), LACCOS, Brasil.

This research was partially supported by the grant number SFRH/ BD/ 62033/ 2009 from Fundação para a Ciência e a Tecnologia (FCT). The authors would like to thank Larissa Papaleo Koelzer for her help in data collection.

Correspondence concerning this article should be addressed to Raquel Bertoldo, Centro de Investigação e Intervenção Social (CIS), ISCTEIUL, Avenida das Forças Armadas, 1649-026 Lisboa, Portugal. Email: raquel_bertoldo@iscte.pt.

Recibido: 04/07/2013 Revisado: 10/09/2013 Aceptado: 12/11/2013.

Abstract

One of the ways to tackle the current environmental crisis is by trying to change beliefs and behaviors through the issuance of new laws. But laws and formal norms only become effective once they are also informally valued. This paper aims at determining whether law-regulated pro-environmental beliefs and behaviors (a) have acquired social value in Brazil, as they have in Europe and (b) pertain to two different construal levels, which could help explain the persistent belief-behavior gap in the environmental field. These two objectives are addressed in two studies using self-presentation and hetero-judgment paradigms. Results confirm the proposed hypotheses and are discussed in terms of social change for sustainability.

Key words: social norms, environmental laws, pro-environmental, sustainability, gap.

Resumen

La actual crisis ambiental puede ser atenuada a través del establecimiento de leyes formales que alteren creencias y comportamientos ambientales. Se tiene como objetivo en este artículo identificar si creencias y comportamientos regulados por ley (a) han adquirido valor social positivo tanto en Brasil como en Europa y (b) pertenecen a diferentes niveles de abstracción, el que podría explicar el persistente gap entre creencias y comportamientos ambientales. Estos objetivos son respondidos a través de dos estudios con los paradigmas de la auto-presentación y del hetero-juzgamiento. Los resultados confirman las hipótesis propuestas y son discutidos en términos de cambios sociales para la sostenibilidad.

Palabras clave: normas sociales, leyes ambientales, proambiental, sostenibilidad, gap.

The international community currently faces the major challenge of addressing the environmental crisis (IPCC, 2013; United Nations, 2012). With the aim of controlling this problem, international agreements are established as guides for altering societies' environmental practices to more sustainable ones (Giddens, 2009; Soromenho-Marques, 2005). However, these laws and regulations will only be effective if they acquire an informal and positive social value. In other words, individuals must recognize these laws as social norms in their daily lives (Castro, 2012).

Environmental regulations in Europe are today the expression of what began as civil claims for a more effective environmental protection. Environmental ideas first emerged during the post war years, mixed with antinuclear and counter-culture movements (Douglas & Wildavsky, 1982). At the time, those ideas were marginal and specific of grassroots movements (Castro & Mouro, 2011; Læssøe, 2007). Only after the 70's did a consensus begin to emerge with regard to the importance of protecting the environment (Dunlap, 2008) and the environmental movement started to be institutionalized notably through formal regulations (Castro & Mouro, 2011; Læssøe, 2007).

Today in many countries these concerns are not simply legal and formal - they have become a pre-requisite for being positively seen by others. This is shown by recent studies that demonstrate how pro-environmental beliefs and behaviors have a positive social value in France, in UK (Félonneau & Becker, 2008) and Portugal (Castro & Bertoldo, 2010). Today these regulations are thus in Europe both formally and informally binding. But what about Latin America? How are these concerns evolving from the legal to the informal sphere in Latin-American countries, and particularly in Brazil, where legislative efforts have not been so consensual (Ferreira & Tavolaro, 2008) and are newer than those undertaken by EU member states? Considering that the institutionalization of environmental concerns in Brazil has been more rhetoric than practical (Ferreira & Tavolaro, 2008), our first goal in this paper is to determine whether these formal norms hake taken on an informal social value in that country.

Another aspect that needs to be considered is that, despite the institutionalization of laws and regulations, pro-environmental actions have not changed to the same extent as did beliefs (Vining & Ebreo, 2002). This beliefbehavior gap has been attributed to the concrete difficulties related to changing lifestyles which are dependent on societal structures (Uzzell & Räthzel, 2009), to the lack of specific and pertinent information available to citizens (Kennedy, Beckley, Mcfarlane, & Nadeau, 2009); or to the higher costs of environmental behaviors in relation to attitudes (Kaiser, Byrka, & Hartig, 2010). However, it is also possible to argue that one additional reason for the persistence of this gap, is the fact that general pro-environmental beliefs and behaviors pertain to two different construal levels: an abstract level (represented by pro-environmental beliefs) and a concrete level (represented by pro-environmental behaviors). Considering that abstract information is more contextually-adaptable than concrete information, as a second goal of this paper we propose to analyze how adaptable pro-environmental beliefs and behaviors are to different contexts, and how they are valued. Differences in the social value attributed to each of these levels would indicate that psychosocial processes associated with the influence of norms also help sustain the belief-behavior gap.

In the following two sections we will present the theoretical assumptions behind these questions. The construal level theory (Trope & Liberman, 2003, 2010) will help us better understand the gap between concrete and abstract pro-environmentalism; and the sociocognitive approach to social norms (Dubois, 2003) will help us identify the social value attributed to pro-environmental beliefs and behaviors.

Construal level theory and the environmental belief/behavior gap

Construal level theory is a general theory of psychological distance (Trope & Liberman, 2003) which proposes that "mental construal processes serve to traverse psychological distances and switch between proximal and distal perspectives on objects" (p. 440). Those objects that are psychologically more proximal are represented at a lower construal level, i.e. in a more concrete, specific and detailed way. Those objects that are psychologically more distant are represented at a higher construal level, i.e. in a more abstract and general way. Different types of questions were found to induce different levels of construal (Rabinovich, Morton, Postmes, & Verplanken, 2009). Questions about how one should perform an action lead to answers in a low level of construal, e.g. what is the procedure to do something, or what are the details of a situation. A question about how to save water, for example, could be answered through considerations about closing the tap when brushing one's teeth, choosing specific programs in the washing machine or installing water saving devices. On the other hand, questions about why one should perform an action would lead to high levels of construal, thus eliciting answers about what the meaning or purpose of an action is. In our example, a person could say that s/he saves water in order to reduce the need to extract it from nature, to reduce one's impact in the environment, or simply to save money (Trope, Liberman, & Wakslak, 2007; Trope & Liberman, 2010).

Research using this approach has shown that individuals evaluate their goals differently when using one construal level or another. "Students who considered an academic course to start next academic year (distant future outcome) focused on identity-oriented benefits of the course (e.g. whether the professor treated students with respect). In contrast, when considering a course to start a few days later, participants concentrated on instrumental benefits of the course (e.g. the professor's tendency to give good grades)" (Trope et al., 2007, p. 90). In this example, the psychological distance between idealistic and pragmatic concerns is regarded as requiring a high and a low construal level, respectively (Trope et al., 2007).

This abstract/concrete differentiation could help explain the well-documented belief-behavior gap that is found in very diverse research domains such as climate change (Spence, Poortinga, & Pidgeon, 2011), human rights (Spini & Doise, 1998) or organ donation (Thaler & Sunstein, 2008). The literature shows that the general, abstract principles are more consensual and cross-contextually acceptable than their applied counterparts (Spini & Doise, 1998). These abstract and widely accepted ideas usually indicate the existence of social norms (Dubois, 2003).

Considering the differentiation between the construal levels involved in idealistic and pragmatic concerns (Trope et al., 2007), we propose that pro-environmental beliefs and behaviors imply, respectively, a high (abstract) and a low (concrete) level of construal. And given these differences in construal level, we propose to analyze how adaptable pro-environmental beliefs and behaviors are to different contexts, and how each of them is valued. In the following section we present the sociocognitive approach, which we use to estimate the social value of pro-environmentalism.

The sociocognitive approach to social norms

With the aim of unveiling the social value behind the expression of certain norms, beliefs and behaviors, the sociocognitive approach to social norms has developed a number of experimental paradigms (Gilibert & Cambon, 2003). These paradigms include the self-presentation and the judge paradigms, used in the studies we present in this article.

The self-presentation paradigm consists in "asking subjects to modulate their opinions in a voluntary and strategic fashion" (Gilibert & Cambon, 2003, p. 39) so as to convey either a positive or a negative image of themselves. It is based on the strategies individuals use to be socially acknowledged and appreciated (Schlenker, 1996). Participants are expected to choose the more 'normative' - i.e. the socially valued -options when willing to convey a positive image and to avoid them when willing to convey a negative image.

On the judge paradigm, participants are required to take on the role of evaluators and judge normative and non-normative targets in relation to, for example, their likeability or competence (Gilibert & Cambon, 2003). The importance of this paradigm for the study of norms rests on the fact that participants judge the proposed targets "from the outside, from the point of view of the social collective" (Gilibert & Cambon, 2003, p. 55).

The sociocognitive approach has demonstrated the social value of very diverse (societal) social norms. Studies using these paradigms have demonstrated the positive social value of internality (Dubois, 2008), individualism (Dubois & Beauvois, 2005), belief in a just world (Alves & Correia, 2008, 2010), and ambivalence (Pillaud, Cavazza, & Butera, 2013). What these norms have in common is the fact that they contain ideas that are fundamental for the structures of our modern occidental societies (Beauvois, 2003). And because they are so fundamental, people are well acquainted with the beliefs and behaviors they are expected to show in a formal or professional context (Beauvois & Dubois, 2001), or in a formal vs. a friendly context (Guignard, Apostolidis, & Demarque, submitted).

Previous research in Portugal (Castro & Bertoldo, 2010), France and UK (Félonneau & Becker, 2008) demonstrated that pro-environmental (recycling and water conservation) beliefs and behaviors are valued when participants present themselves to a general other, confirming their positive social value in these countries, in particular among university students of these countries. Furthermore, this social value is context-sensitive - i.e., self-presentations in a pro-normative context show a higher valorization of pro-environmental beliefs and behaviors than in an anti-normative context (Castro & Bertoldo, submitted). However, these studies were conducted in European Union member-states, where laws now regulate the environmental behaviors proposed for the self-presentations: waste separation and energy efficiency1.

As in other countries worldwide, environmental debate in Brazil has led to a growing awareness of the importance of environmental issues (Dunlap, Gallup & Gallup, 1993; Ferreira, 2000). Yet the Brazilian political scene is, in what concerns environmental issues, still characterized by more rhetoric than practical concerns: extremely sophisticated legal instruments and an increasingly complex institutional apparatus have very limited conditions for implementation (Ferreira & Tavolaro, 2008). These political aspects are also indicative of a weak environmental debate in the Brazilian society as a whole. This is why we are interested in assessing whether pro-environmental beliefs and behaviors in the Brazilian society have achieved the social value that they achieved in Europe.

Specific objectives

Our objective in this paper is twofold. Our first goal is to verify if pro-environmental beliefs and behaviors have a positive social value in Brazil, as they have in some European Union member-states, where pro-environmental laws are more effective in promoting these behaviors (Castro & Bertoldo, 2010; Félonneau & Becker, 2008). That is, if they are deemed necessary in positive self-presentations and if they determine positive evaluations when seen in a target. Our second goal is to compare the valorization of expressing pro-environmental beliefs (abstract) and behaviors (concrete): is their expression and judgment similar or do they correspond to different social logics?

These two goals will be simultaneously addressed in two studies, each using a different paradigm: self-presentation and hetero-evaluation. These two ways of assessing the social value rely on different social processes - one requiring participants' conformity and respect to a norm; and another where the participant is socially detached form the situation and is asked to act as a judge. These two paradigms are considered to be complementary because, through different processes, they demonstrate the social value of an object (Gilibert & Cambon, 2003).

Study 1: Self-presentation in context

In line with the literature we assume that people are aware of what is socially expected from them in different contexts (Beauvois & Dubois, 2001; Jellison & Green, 1981). So, in this study we shall use the self-presentation paradigm, but considering specific targets. Instead of asking participants to present themselves to a general other (Gilibert & Cambon, 2003), we specified the target they were presenting themselves to: a pro-normative or an anti-normative target (following the procedure of Castro & Bertoldo, submitted). This procedure also aimed at avoiding the ceiling effect found by Félonneau and Becker (2008), where participants expressed their pro-environmental beliefs by using the extremes of the scales for a positive (or negative) presentation.

These pro or anti-normative targets were chosen through a pilot study (N = 72, Portuguese university students, 68% female) where 12 different contexts were proposed to participants. Participants considered the 'ecological institute' context to be the most pro-environmental, and the 'cement plant' context to be the most anti-environmental (Bertoldo, Castro & Serdült, 2012). We have assumed that these contexts would be similarly evaluated by Brazilian students.

We also wanted to avoid respondents answering the positive and negative presentation questionnaires in an automatic way, by just reversing the positive or negative answers given in the first place. We have thus used a between-subjects design, which provides a stronger evidence of social value (Alves & Correia, 2008). We had therefore a 2 (positive or negative presentation) X 2 (pro or antinormative context) between-subjects plan.

A previous study has shown that Portuguese participants value environmental beliefs and behaviors in a pro-normative context (they presented different beliefs and behaviors for a positive and for a negative presentation). The same study has also shown that this difference is not observed in an anti-environmental context (Castro & Bertoldo, submitted). What we do not know is if, as a result of more lenient formal norms, the environmental beliefs and behaviors are less valued in Brazil than they are in Europe.

Hypotheses

H1) We expect participants to use the scales measuring pro-environmental beliefs and behaviors scales in a strategic way: displaying higher scores for beliefs and behaviors when presenting a positive self-image and lower scores for beliefs and behaviors when presenting a negative image. If they do so, pro-environmentalism is also confirmed as socially valued among Brazilian university students.

H2) Based on previous studies (Castro & Bertoldo, submitted), we hypothesize this social value to be contextsensitive. We expect participants' scores to display differences between a positive and a negative presentation in a pronormative context (environmental institute) and not to display them in an anti-environmental context (cement plant), which would indicate that the social value of proenvironmental beliefs and behaviors is only clear in the pronormative context. If this hypothesis is confirmed, we will demonstrate that pro-environmental beliefs and behaviors are still differently valued depending on the context, indicating that, as in Portugal (Castro & Bertoldo, submitted), they are not yet fully generalized (Castro, 2012).

H3) The construal level theory (Trope & Liberman, 2010) proposes that abstract (high construal level) information is more contextually adaptable than concrete (low construal level) information. This is why we expect the expression of pro-environmental beliefs to show higher differences - between a positive and a negative presentation-, than the expression of behaviors, between the presentation contexts. This easiness to contextually adapt the expression of beliefs - in relation to that of behaviors - also would indicate that they are more easily adaptable to environmental social norms, what can in turn help explain the gap found between pro-environmental beliefs and behaviors (Dunlap, 1991; Kennedy et al., 2009).

Method

Participants. A total of one hundred and seventy-six students from the Federal (UFSC) and the State (UDESC) Universities of Santa Catarina (Brazil) participated in the study. They were students in Social Service, Sanitary and Environmental Engineering, Geography, and Business Administration. Participants were in average 23.7 (17-49, SD = 4.6) years old and 52.3% of them were male.

Procedure. Participants answered the questionnaire during a class. After a brief oral introduction, participants were asked to carefully read a scenario of the situation they should consider when responding to the questionnaire. These scenarios described the context (ecological institute or cement plant) and the type of presentation (positive or negative) in four pre-tested paragraphs.

The four scenarios described a situation where the respondent was participating in a selection process for an internship in one of the above-mentioned contexts. The organizations' intentions and interests towards the environment were made explicit: the ecological institute was described as "very active in exerting public pressure for the respect of environmental laws and regulations", while the cement plant was described as "publicly known to suffer pressure from environmental groups because of the environmental impact of its extractive activities". Respondents were asked to convey either a positive selfimage (when the job was good and they wanted it) or a negative one (when the job was bad and they did not want it).

The questionnaire contained items of beliefs and behaviors from the private sphere (Stern, 2000) - recycling, energy and water conservation - already used in previous studies (Castro, Garrido, Reis, & Menezes, 2009; Félonneau & Becker, 2008). On the last page of the questionnaire, participants were required to provide demographical information (age, gender, and faculty). At the end of the session participants were debriefed and thanked.

Formal evaluations such as job interviews or school evaluations constitute situations where social norms are especially active (Beauvois & Dubois, 2001; Dubois, 2000). Students invited to participate in this study were relatively advanced on their graduate studies (3rd and 4th years), and probably seeking an internship. Additionally, considering their faculties, our participants could potentially be interested in an internship in one of the proposed scenarios (e.g. Geography, Biology, Environmental Engineering and Management).

Instruments

Beliefs. Seven items were used to assess participants' conservation beliefs (e.g., reducing my water consumption makes no difference for the environment; recycling is a business which only favors some people -reversed). Answers ranged from 1 - totally disagree, to 7 - totally agree. The items were averaged in a single score (α = .67).

Behaviors. Eleven items were used to assess participants' conservation behaviors (e.g., At home, I do not bother saving energy - reversed; I put my batteries away in the containers provided). Answers ranged from 1 - never, to 7 - always. The items were averaged in a single score (α = .75).

Results

We performed two 2 (presentation type: positive and negative) X 2 (target: environmental institute and cement plant) ANOVAs, one on the pro-environmental beliefs scale and another on the behaviors scale. A main effect of the presentation type was found for beliefs (M pos = 5.54 and Mneg = 5.18; F(1,160) = 8.0, p < .01). The same main effect was also found for behaviors (M = 4.47 and Mposneg = 4.13; F(1,165) = 5.5, p < .05). This result indicates that, in general, pro-environmental beliefs and behaviors receive higher scores for a positive than for a negative presentation, thus confirming H1.

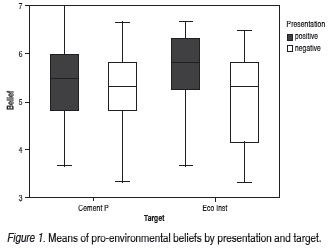

A marginally significant interaction effect was also found between presentation type and target for the expression of beliefs (F(1,160) = 3.52, p = .06), as it can be observed in Figure 1. No interaction effect was found for behaviors (F(1,165) = .9, p = ns). This result indicates that the difference between a positive and a negative presentation across contexts is significant for the expressed beliefs, but not for behaviors. This result indicates an easier adaptability of the expressed beliefs between contexts, thus confirming H3.

The interaction found between the presentation type and the target in the expression of beliefs was also analyzed through t tests comparing the difference between the positive and negative presentations in each of the contexts. These results show that participants express different beliefs for a positive and for a negative presentation when presenting themselves to an ecological institute employer (Mpos = 5.7 and Mneg = 5.0; t(77) = 3.1, p < .01), but not to a cement plant employer (Mpos = 5.4 and Mneg = 5.3; t(83) = .7, ns). This result shows that the presentation context is still an important aspect of the social value attributed to these ideas. Given that this result was only found for environmental behaviors, H2 is partially confirmed.

Discussion

Our results indicate that, in general, pro-environmental beliefs and behaviors have acquired a positive social value in Brazil - they are differently used in a positive or negative presentation, irrespective of their presentation context -, thus confirming H1. Pro-environmental ideas have spread quickly around the world since the 70's (Dunlap et al., 1993), to the point of becoming today a requirement for a positive presentation in some European Union member states. Our results in study 1 demonstrate that pro-environmental beliefs and behaviors are positively valued among Brazilian university students, as they have seen to be among Portuguese (Castro & Bertoldo, 2010), French and English students (Félloneau & Becker, 2008).

However, these results also show that despite this generally positive social value, the expression of proenvironmental beliefs and behaviors is still contextsensitive - especially concerning beliefs. Differences between the positive and the negative presentations are only observable in a pro-normative condition (ecological institute) - not in an anti-normative condition (cement plant) - and only for the expression of beliefs, thus partially confirming H2. Our results are similar to those found in Portugal (Castro & Bertoldo, submitted) where, despite their social value, environmental ideas are not yet generalized to all contexts.

Moreover, interaction between the type of presentation and the target in Brazil indicates that the expression of pro-environmental beliefs is more contextually adaptable than that of pro-environmental behaviors; this supports H3. The easier contextual adaptation of abstract in relation to concrete pro-environmentalism (Trope & Liberman, 2010) indicates that, at least in the environmental field, it is much easier and seems to be quicker to make ideas - rather than actions - correspond to social norms. This result provides an alternative interpretation for the gap between environmental beliefs and behaviors (Dunlap, 1991; Kennedy et al., 2009). Based on the construal level theory (Trope et al., 2007; Trope & Liberman, 2010) we have shown in this study that questions about beliefs or behaviors entail two different ways of responding to environmental social norms: one that is general and unspecific and another one that is concrete and specific. And if this difference between the expression of beliefs and behaviors was found through self-reports - which are subject to consistency pressure -, we can expect it to be even greater in real life situations.

This study was able to demonstrate the more adaptable nature of pro-environmental beliefs in relation to behaviors through assessing participants' self-presentations. But are these strategies - used by people when presenting themselves - really successful for a positive social judgment? How important are pro-environmental beliefs in comparison to behaviors when one is being socially judged? The next study intends to answer this question.

Study 2: Social judgments

Following the findings that pro-environmentalism is socially valued in Brazil - at least among university students - and that the expression of beliefs is more context-adaptable than behaviors, in this study we aim at comparing the importance of abstract (beliefs) and concrete (behaviors) pro-environmentalism for being positively judged.

To do so, we used the judge paradigm (Gilibert & Cambon, 2003), in a task where participants were required to evaluate targets known only for their answers to a questionnaire - in our case, the same pro-environmental beliefs and behaviors scale used in Study 1. Participants are asked to (1) form an impression of the target that supposedly answered the questionnaire and (2) rate this target in two traits. These traits corresponded to the two basic dimensions of intergroup (Fiske, Xu, Cuddy, & Glick, 1999) and interpersonal (Judd, James-Hawkins, Yzerbyt, & Kashima, 2005; Russell Fiske, 2008 perception: warmth and competence.

In this study, we aim at assessing the social value of abstract beliefs in relation to their concrete counterparts, behaviors. We propose that behaviors (in relation to beliefs) have the potential to differentiate those individuals presenting, beyond the ideas, behaviors - which are more difficult and costly (Kaiser et al., 2010). A recent study in Portugal confirmed that participants attributed more competence to a target presenting concrete proenvironmentalism in relation to a target that did not (Castro & Bertoldo, submitted).

Considering the more rhetoric than practical adoption of pro-environmental laws in Brazil, and the not-so-high resonance of pro-environmental ideas in the Brazilian public opinion (Ferreira, 1998; Ferreira & Tavolaro, 2008), will participants also judge more positively a target presenting a concrete (vs. abstract-only) pro-environmentalism? We will measure the competence and warmth attributed to these two targets. The study contains thus a 2 (profile: high beliefs & behaviors/high beliefs & low behaviors) X 2 (evaluation dimension: competence/warmth) plan, between subjects on the first factor and within subjects on the second.

The two targets have one similarity and one difference. Their difference is that the high beliefs & behaviors target presents concrete pro-environmentalism whether the high beliefs & low behaviors target does not. And their similarity is that both present abstract pro-environmentalism, or beliefs.

Hypotheses

H1) Following results of Study 1 about the social value attributed to pro-environmentalism, and observing the pattern of results found for the attribution of competence in Portugal, if their difference in terms of the concrete pro-environmentalism leads to an increased attribution of competence, this dimension can be associated to concrete pro-environmentalism (behaviors).

H2) Following the result pattern found in Portugal for the attribution of warmth, if their similarity in terms of abstract pro-environmentalism leaves their attribution of warmth unchanged, this dimension can be associated to abstract pro-environmentalism.

Method

Participants. Seventy students from the Universidade Federal de Santa Catarina (Brazil) participated in the study. From these participants, 55 correctly answered the manipulation check question, leaving 28 participants in the high and 27 in the low pro-environmental condition.

Procedure. Participants were invited to participate of the study during a class. They received a pre-filled questionnaire - the same used in Study 1 - and were informed that it had been filled out by a university student from the previous semester. We asked them to imagine, as they read the answers, what that person was like. After they read the supposed target's answers, participants were requested to describe, in their own words, how they imagined that person to behave and think about the environment. This was a filler task with the objective of enhancing the profile manipulation. Then, participants were asked to estimate how characteristic of the target a series of competence and warmth traits were (Fiske et al., 1999). When participants finished responding, they were debriefed and thanked.

The answers presented in the pre-filled questionnaires were based on the means of a pre-test of the pro-environmental beliefs and behaviors scales (Castro & Bertoldo, 2010), one standard deviation was added - when the profile presented a high score - or subtracted - when the profile presented a low score. The two stimulus questionnaires presented the following profiles: high beliefs & behaviors and high beliefs & low behaviors.

As a manipulation check, participants were asked to state, in the end of the questionnaire whether the presented target expressed (1) pro-environmental beliefs and (2) proenvironmental behaviors in a scale from 1 - "not at all" to 7 - "very much". Participants who gave wrong answers or could not remember the target manipulation were excluded from the analyses.

Instruments. According to the dimensions proposed by Fiske and colleagues (1999), the competence score was the average rating of the target in the following adjectives, answered in a scale from 1 -not characteristic at all to 7- very characteristic: confident, talented, intelligent, capable and competent, from 1 (not characteristic at all) to 7 (very characteristic) (α = .79). The warmth score was the average of the ratings of the target in the following adjectives: goodnatured, friendly, tolerant and warm (α= .67).

Results

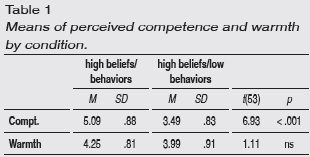

We performed a 2 (dimension: competence or warmth) X 2 (target: high beliefs and behaviors or high beliefs and low behaviors) ANOVA with repeated measures on the first factor. Results show a main effect of target (F(1,53) = 19.2, p < .001), no main effect of dimension and an interaction between target and dimension (F(1,53) = 37.3, p < .001) - Table 1.

So as to understand in which dimension(s) the two targets were different, two separate t tests were performed on their perceived competence and warmth. As shown in Table 1, competence ratings are higher for the target presenting high behaviors. This result indicates that concrete proenvironmentalism can be associated with the attribution of competence, thus confirming H1.

Warmth ratings, on the other hand, did not distinguish the two targets. Given that this was the dimension where both targets were equal, abstract pro-environmentalism can be associated with the attribution of warmth, thus confirming H2.

Discussion

Two targets presenting different levels of concrete proenvironmentalism (high or low behaviors) and equal levels of abstract pro-environmentalism (beliefs) were submitted to the judgement of Brazilian participants in terms of warmth and competence (Fiske, Cuddy, & Glick, 2002; Fiske et al., 1999). Consistent with our hypothesis, the competence dimension was more attributed to the target presenting high concrete pro-environmentalism (behaviors). Considering the social value of pro-environmentalism shown in Study 1, this result specifies that the expression of pro-environmental behaviors is associated with perceived competence - the simple expression of pro-environmental beliefs is not sufficient (H1).

On the other hand, targets had a similarity: their expressed pro-environmental beliefs. Considering that they were equally rated on this dimension, this result indicates that warmth can be associated with the expression of abstract pro-environmentalism (H2).

Overall, this study shows that pro-environmental behaviors can act as a social differentiator, in terms of competence perception. But the expression of proenvironmental beliefs seems to be a social requirement.

General discussion

The environmental crisis presents the international community with one of its greatest challenges (United Nations, 2012). One of the ways through which this problem is tackled is in the legal arena: international legal frameworks are transcribed to the national laws, and locally implemented (Castro & Mouro, 2011; Ferreira, 2000). Considering that this process evolved from the public opinion to the legal sphere in a more consistent and quick way in European Union member states than in Brazil (Ferreira & Tavolaro, 2008), we wanted to verify whether this formal valorization led to a different informal valorization between Portuguese and Brazilian participants. And secondly, from the distinction between high and low levels of construal (Trope & Liberman, 2010), we proposed that pro-environmental norms can generate different levels of informal alignment: an abstract alignment - seen through the expression of pro-environmental beliefs - and a concrete alignment - when pro-environmental behaviors are also shown. This paper explored these objectives through two paradigms of the sociocognitive approach: the self-expression (study 1) and hetero-judgment (study 2).

Confirming the results of previous applications of the sociocognitive paradigms in Portugal (Castro & Bertoldo, 2010), France and UK (Félonneau & Becker, 2008), we have seen that Brazilian university students value proenvironmental beliefs and behaviors to the point of being able to strategically use them to present themselves (study 1). We have also seen that this valorization is contextsensitive. Differences between the expressed beliefs were only observed in a pro-normative condition (ecological institute), but not in an anti-normative condition (cement plant). These results indicate that despite the fact that the public debate and the institutionalization of environmental concerns have been less intense in Brazil in comparison to European countries, pro-environmental beliefs and behaviors are similarly valued among university students in Brazilian and in Portugal.

Regarding the specific usages of pro-environmental beliefs in relation to behaviors, our results have shown that differences between positive and negative presentations were, in a pro or anti-normative context, higher for the expressed beliefs than for the expressed behaviors. This result attests an easier alignment of abstract (vs. concrete) pro-environmentalism to normative contexts (Trope & Liberman, 2010). And since their presentation is more adaptable to normative contexts, pro-environmental beliefs are also more adaptable to environmental social norms in general. This result provides an alternative interpretation for the gap between environmental beliefs and behaviors (Dunlap, 1991; Kennedy et al., 2009) which is based on the different ways that idealistic and pragmatic information is processed. Questions about why someone does something lead to much more general and abstract answers than questions about how one does these things, which lead to more specific and concrete concerns (Trope et al., 2007). On the other hand, questions about more specific beliefs and behaviors (i.e. about recycling) have already shown no 'gap' (Nigbur, Lyons, & Uzzell, 2010), in a region where the laws, the informal norms and the structural conditions all converge to foster recycling. This may indicate, from one side, that this gap may exist to a larger extent for broader (vs. specific) issues; and from the other, that in time idealistic and pragmatic goals may end up converging. If this convergence never happened, new laws proposing behavior change would be useless.

These results were complemented by a second study that used the hetero-judgment paradigm to test if the strategies used by participants in the first study were actually successful in transmitting the image they intended to transmit. Results show that a target presenting concrete pro-environmentalism was rated as more competent than a target not presenting it. On the other hand, both targets presented equally high pro-environmental beliefs, and were also rated as equally warm. These results demonstrate how the presence of proenvironmental behaviors differentiate a target presenting concrete pro-environmentalism in relation to a target only presenting abstract pro-environmentalism. Moreover, the expression of abstract pro-environmentalism - be it accompanied or not by their corresponding behaviors - is today a requirement for the perception of warmth (Fiske et al., 2002), and thus for the perception of social proximity. Results of the competence and warmth dimensions are similar to those found in Portugal (Castro & Bertoldo, submitted) with a similar student sample.

We have performed in these studies a comparative analysis of the social value associated with beliefs and behaviors, which is a central dimension for understanding the legal change process (Castro, 2012). Laws and regulations do reflect the abstract political orientations of a country even if their restrictive power is only observable at the concrete level of behaviors. Therefore, an analysis of the concrete and the abstract valorization is important to understand the gap existing between regulations and their concrete efficacy.

On the whole, these studies were able to demonstrate that pro-environmental ideas and behaviors are today informally valued in Brazil, despite a more recent debate on the matter (Ferreira & Tavolaro, 2008) in relation to the debate found in European Union member-states (Castro, Mouro, & Gouveia, 2012; Melo & Pimenta, 1993). The participants of these studies were university students, what calls for a particularization of these results. At least among university students -in EU countries as well as in Brazil- , environmental ideas are positively valued, pro-environmental behaviors being a distinctive feature. These results point to two different aspects. First of all, they could suggest that the ideas and practices of university students are more similar and stable across countries than we had anticipated. Brazilian and European university students are a highly educated, globalized, group and seem to adhere to similar environmental values. Through their access to similar cultural goods, university students share a common background that possibly makes them resemble more other countries' university students than their own country's population. These results could also suggest that the valorization of these ideas by university students mirrors a wider valorization of these ideas in the Brazilian and Portuguese societies as a whole. In this case, their similarity could indicate a wider similarity between the adherence to pro-environmental ideas in Portugal and Brazil. In any case, an assessment integrating other social groups, besides university students, is needed in order to have a clearer idea of the actual social value of environmental ideas in these countries.

Pie de página

1 See Directive 2008/98/EC (Waste Directive) and Directives 2004/8/EC and 2006/32/EC (energy efficiency).

References

Alves, H., & Correia, I. (2008). On the normativity of expressing the belief in a just world: Empirical evidence. Social Justice Research, 21, 106-118. doi: 10.1007/s11211-007-0060-x. [ Links ]

Alves, H., & Correia, I. (2010). The strategic expression of personal belief in a just world. European Psychologist, 15, 202-210. doi: 10.1027/1016-9040/a000020. [ Links ]

Beauvois, J.-L. (2003). Judgment norms, social utility, and individualism. In N. Dubois (Ed.), A sociocognitive approach to social norms (pp. 123-147). London: Routledge. [ Links ]

Beauvois, J.-L., & Dubois, N. (2001). Normativity and self-presentation: Theoretical bases of selfpresentation training for evaluation situations. Journal of Managerial Psychology, 16, 490-508. doi: 10.1108/EUM0000000006164. [ Links ]

Bertoldo, R., Castro, P., & Serdült, S. (2012). Conservation ideas and behaviours in different meta-normative settings. 11ª Conferência Internacional de Representações Sociais, Universidade de Évora, 25-29 June, Évora, Portugal. [ Links ]

Castro, P. (2012). Legal innovation for social change: exploring change and resistance to different types of sustainability laws. Political Psychology, 33, 105-121. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9221.2011.00863.x. [ Links ]

Castro, P., & Bertoldo, R. B. (2010). Context influence on the expression of conservation normativity. 21st IAPS Conference 'Vulnerability, Risk and Complexity: Impacts of Global Change on Human Habitats', Helmholtz Centre for Environmental Research, 27 June - 2 July, Leipzig, Germany. [ Links ]

Castro, P., & Bertoldo, R. B. (submitted). If I express new ideas, can I maintain old actions for a while? Impression management and low-carbon lifestyles. [ Links ]

Castro, P., & Mouro, C. (2011). Psycho-social processes in dealing with legal innovation in the community: Insights from biodiversity conservation. American Journal of Community Psychology, 47, 362-73. doi: 10.1007/s10464-010-9391-0. [ Links ]

Castro, P., Garrido, M., Reis, E., & Menezes, J. (2009). Ambivalence and conservation behaviour: An exploratory study on the recycling of metal cans. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 29, 24-33. doi: 10.1016/j.jenvp.2008.11.003. [ Links ]

Castro, P., Mouro, C., & Gouveia, R. (2012). The conservation of biodiversity in protected areas: Comparing the presentation of legal innovations in the national and the regional press. Society & Natural Resources, 25, 539-555. [ Links ]

Douglas, M., & Wildavsky, A. (1982). Risk and culture: an essay on the selection of technological and environmental dangers. Berkeley: University of California Press. [ Links ]

Dubois, N. (2000). Self-presentation strategies and social judgments - desirability and social utility of causal explanations. Swiss Journal of Psychology, 59, 170-182. doi: 10.1024//1421-0185.59.3.170. [ Links ]

Dubois, N. (2003). Introduction: The concept of norm. In N. Dubois (Ed.), A sociocognitive approach to social norms (pp. 1-16). London: Routledge. [ Links ]

Dubois, N. (2008). La norme d'internalité et le libéralisme. Grenoble: Presses Universitaires de Grenoble. [ Links ]

Dubois, N., & Beauvois, J.-L. (2005). Normativeness and individualism. European Journal of Social Psychology, 35, 123-146. [ Links ]

Dunlap, R. E. (1991). Public opinion in the 1980s: Clear consensus, ambiguous commitment. Environment, 33, 10-37. [ Links ]

Dunlap, R. E. (2008). The new environmental paradigm scale: From marginality to worldwide use. The Journal of Environmental Education, 40, 3-18. doi: 10.3200/JOEE.40.1.3-18. [ Links ]

Dunlap, R., Gallup, G., & Gallup, A. (1993). Of global concern: Results of the Health of the Planet Survey. Environment, 35, 7-39. [ Links ]

Félonneau, M.-L., & Becker, M. (2008). Pro-environmental attitudes and behaviour: Revealing perceived social desirability. Revue Internationale de Psychologie Sociale, 21, 25-53. [ Links ]

Ferreira, L. C. (1998). A questão ambiental: Sustentabilidade e políticas públicas no Brasil. São Paulo: Boitempo Editorial. [ Links ]

Ferreira, L. C. (2000). Indicadores político-institucionais de sustentabilidade: Criando e acomodando demandas públicas. Ambiente & Sociedade, 3, 15-31. [ Links ]

Ferreira, L. C., & Tavolaro, S. B. F. (2008). Environmental concerns in contemporary Brazil: An insight into some theoretical and societal backgrounds (1970s-1990s). International Journal of Politics, Culture, and Society, 19, 161-177. doi: 10.1007/ s10767-008-9021-0. [ Links ]

Fiske, S. T., Cuddy, A. J. C., & Glick, P. (2002). A model of (often mixed) stereotype content: Competence and warmth respectively follow from perceived status and competition. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 82, 878-902. doi: 10.1037/00223514.82.6.878. [ Links ]

Fiske, S. T., Xu, J., Cuddy, A. C., & Glick, P. (1999). (Dis)respecting versus (dis)liking: Status and interdependence predict ambivalent stereotypes of competence and warmth. Journal of Social Issues, 55, 473-489. [ Links ]

Giddens, A. (2009). The Politics of Climate Change. Cambridge: Polity Press. [ Links ]

Gilibert, D., & Cambon, L. (2003). Paradigms of the sociocognitive approach. In N. Dubois (Ed.), A sociocognitive approach to social norms (pp. 38-69). London: Routledge. [ Links ]

Guignard, S., Apostolidis,T., & Demarque, C. (submitted). From theoretical definition to operationalization of Future Time Perspective construct: Discussing normative issues. [ Links ]

IPCC (2013). Working Group I contribution to the IPCC fifth assessment report: Synthesis for policymakers. Retrieved from http://www.climatechange2013.org/images/uploads/WGIAR5-SPM_Approved27Sep2013.pdf. [ Links ]

Jellison, J. M., & Green, J. (1981). A self-presentation approach to the fundamental attribution error: The norm of internality. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 40, 643-649. doi: 10.1037/00223514.40.4.643. [ Links ]

Judd, C. M., James-Hawkins, L., Yzerbyt, V., & Kashima, Y. (2005). Fundamental dimensions of social judgment: Understanding the relations between judgments of competence and warmth. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 89, 899-913. doi: 10.1037/00223514.89.6.899. [ Links ]

Kaiser, F. G., Byrka, K., & Hartig, T. (2010). Reviving Campbell's paradigm for attitude research. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 14, 351-367. doi: 10.1177/1088868310366452. [ Links ]

Kennedy, E. H., Beckley, T. M., Mcfarlane, B. L., & Nadeau, S. (2009). Why we don't "walk the talk": Understanding the environmental values/behaviour gap in Canada. Human Ecology Review, 16, 151-160. [ Links ]

Læssøe, J. (2007). Participation and sustainable development: The post-ecologist transformation of citizen involvement in Denmark. Environmental Politics, 16, 231-250. doi: 10.1080/09644010701211726. [ Links ]

Melo, J. J., & Pimenta, C. (1993). O que é ecologia e ambiente. Lisboa: Difusão Cultural. [ Links ]

Nigbur, D., Lyons, E., & Uzzell, D. (2010). Attitudes, norms, identity and environmental behaviour: Using an expanded theory of planned behaviour to predict participation in a kerbside recycling programme. The British Journal of Social Psychology, 49, 259-84. doi: 10.1348/014466609X449395. [ Links ]

Pillaud, V., Cavazza, N., & Butera, F. (2013). The social value of being ambivalent: Self-presentational concerns in the expression of attitudinal ambivalence. Personality & Social Psychology Bulletin, 39, 1139-51. doi: 10.1177/0146167213490806. [ Links ]

Rabinovich, A., Morton, T. A., Postmes, T., & Verplanken, B. (2009). Think global, act local: The effect of goal and mindset specificity on willingness to donate to an environmental organization. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 29, 391-399. doi: 10.1016/j.jenvp.2009.09.004. [ Links ]

Russell, A. M. T., & Fiske, S. T. (2008). It's all relative: Competition and status drive interpersonal perception. European Journal of Social Psychology, 38, 1193-1201. doi: 10.1002/ejsp.539. [ Links ]

Schlenker, B. R. (1996). Impression management. In: A.S. Manstead & M. Hewstone (eds.), The Blackwell Encyclopedia for Social Psychology (pp. 314-319), Oxford: Blackwell. [ Links ]

Soromenho-Marques, V. (2005). A constelação ambiental - metamorfoses da nossa visão do mundo. In L. Soczka (Org.), Contextos Humanos e Psicologia Ambiental. (pp. 11-38). Lisboa: Fundação Calouste Gulbenkian. [ Links ]

Spence, A., Poortinga, W., & Pidgeon, N. (2011). The psychological distance of climate change. Risk Analysis, 32, 957-972. doi: 10.1111/j.1539-6924.2011.01695.x. [ Links ]

Spini, D., & Doise, W. (1998). Organizing principles of involvement in human rights and their social anchoring in value priorities. European Journal of Social Psychology, 28, 603-622. [ Links ]

Stern, P. C. (2000). Toward a coherent theory of environmentally significant behavior. Journal of Social Issues, 56, 407-424. [ Links ]

Thaler, R.H., & Sunstein, C.R. (2008) Nudge: Improving decisions about health, wealth and happiness. New Haven: Yale University Press. [ Links ]

Trope, Y., & Liberman, N. (2003). Temporal construal. Psychological Review, 110, 403-421. doi: 10.1037/0033295X.110.3.403. [ Links ]

Trope, Y., & Liberman, N. (2010). Construal-level theory of psychological distance. Psychological Review, 117, 440-463. doi: 10.1037/a0018963. [ Links ]

Trope, Y., Liberman, N., & Wakslak, C. (2007). Construal levels and psychological distance: Effects on representation, prediction, evaluation, and behavior. Journal of Consumer Psychology, 17, 83-95. [ Links ]

United Nations (2012). Realizing the future we want for all: Report to the Secretary-General. Retrieved from: http://www.un.org/en/development/desa/policy/untaskteam_undf/untt_report.pdf. [ Links ]

Uzzell, D., & Räthzel, N. (2009). Transforming environmental psychology. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 29, 340-350. doi: 10.1016/j.jenvp.2008.11.005. [ Links ]

Vining, J., & Ebreo, A. (2002). Emerging theoretical and methodological perspectives on conservation behavior. In R. B. Bechtel, & A. Churchman (Eds.), Handbook of environmental psychology (pp. 541-558). New York: Wiley. [ Links ]