Discrimination and violence based on homonegativity are examples of social and environmental factors that can impact mental health and wellbeing (Hatzenbuehler, 2009; Hatzenbuehler, Nolen-Hoeksema, & Dovidio, 2009; Meyer, 1995, 2003). Homonegativity, also known as homophobia, is understood as hatred, fear or aversion towards lesbian, gay, bisexual and trans (LGBT) people (Herek, 2004; UNESCO, 2015). Homonegativity is expressed at different levels, including the individual's own negative believes about their non-heterosexual sexuality, which usually have an impact on physical and mental health of lesbian and bisexual women (LBW) (Meyer, 2003; Ross & Rosser, 1996). Research also shows that belonging to a group and a community are useful in developing coping skills to face homonegativity and its consequences (Frost & Meyer, 2009, 2012).

Mexican studies demonstrate that LBW wellbeing, health, and identity are understudied and invisibilized by academia, policy, and activism (Navarro, 2016; Vergara, 2012). Little is known about their health, including the fact that that nearly 90% of lesbian women consume alcohol, and 5% drinks at least twice a week (ESPOLEA & INSADE, 2015). Available research from other countries shows that LBW experience discrimination and violence and that this is related to mental health issues, such as higher risk of suicide, higher levels of alcohol use, and lower frequency of attending sexual health services (Cochran & Mays, 2006; Kaminski, 2000; Meyer, Frost, & Nazhad, 2015; Mustanski, Garofalo, & Emerson, 2010; Powers, Bowen, & White, 2001).

Vulnerability of lesbian and bisexual women

Mexican women are usually at a greater risk of living violence as victims, depression, anxiety, and sexually transmitted infections (STIs) (Padilla-Gámez & Cruz del Castillo, 2014). Additionally, they are paid less than men for doing the same job, are more likely to live in poverty and be depressed than men, regardless of their sexual orientation, and also face more barriers to access health services than men (Moctezuma, Narro, & Orozco, 2014).

Sex and gender systems play a fundamental role in the development of women's vulnerability and produce what was originally called homophobia; this was later renamed homonegativity or sexual stigma (Herek, 2004). Mexico has been described as having a patriarchal gender system in which men and masculinity are almost always more highly valued than women and femininity (Lagarde, 1997). An example of this is the violence women experience because of their gender. The National Survey on Home Dynamics (ENDIREH, 2016) shows that 34.3% of Mexican women aged 15 or older have been victims of some sort of violence in public spaces.

Heteronormativity (Warner, 1993), is understood as the norms that regulate sexual experience, localized practices, within centralized institutions that privilege heterosexuality and contribute to the idea that men and women are sexually complementary (Cohen, 1997). These systems build the notion that heterosexuality is the only valid form of sexual expression and that reproduction is the sole purpose of sexuality (Ortíz-Hernández, 2005). The combination of these two systems places men, masculinity, and heterosexuality as being more valid and important than other identities and gender expressions. As a consequence, LBW may experience double forms of discrimination and vulnerability: as both women and non-heterosexuals.

Discrimination and violence against lesbian and bisexual women

Lesbian and bisexual women experience more stress and distress compared to heterosexuals, and this stress elevates emotional discomfort (Meyer, 1995, 2003) and social and cognitive problems (Hatzenbuehler, 2009). According to Mendoza, Ortiz, and Román (2016), 68% of LBW report to having been discriminated against due to their sexual orientation and/or gender. Data also show that 43.5% of lesbians have been insulted or threatened, 11.2% have been physically attacked, and almost 27% have been victims of sexual violence (Lozano-Verduzco & Salinas-Quiroz, 2016). Data from other countries shows that LBW are victims of homophobic bullying on a considerable level (Rodrigues, Grave, de Olveira, & Nogueira, 2016).

Frómeta and Ponce (2013), found that LBW reported having been victims of psychological violence, were expelled from their family home after assuming a lesbian identity, and were constantly accused of perversion and immorality. They also reported having to make a serious effort in order to gain social recognition in their professional and family lives. Studies show that discrimination and violence affect LBW's sense of self, relationships, and wellbeing (Frost & Meyer, 2009; Kertzner, Meyer, Frost, & Stirrat, 2009; Meyer, Ouellette, Haile, & McFarlane, 2011).

Internalized homonegativity and mental health in lesbian and bisexual women

Internalized forms of stigma are commonly found among LBW and are usually associated with social homonegativity and community connectedness (Lozano-Verduzco, Fernández-Niño, & Baruch-Domínguez, 2017; Navarro, 2016; Ortíz-Hernández, 2005; Ross & Rosser, 1996) and with decreased mental health status (Frost & Meyer, 2012; Newcomb & Mustanski, 2010; Ortíz-Hernández, 2005). Understanding variables such as community connectedness and internalized homonegativity may allow us to better reflect on connections between discrimination and health outcomes (Mendoza & Ortíz-Hernández, 2018: Morandini, Blaszczynski, Costa, Godwin, & Dar-Nimrod, 2017). According to Frómeta and Ponce (2013) lesbian women decide not to "come out" until approximately five years after having assumed a lesbian identity because of emotions such as insecurity, fear, and uncertainty due to lack of social and family acceptance and a fear of being discriminated against for not following heterosexual norms.

Ortíz-Hernández, Gómez, and Valdéz (2009) found that Mexican LBW tend to consume more alcohol and cigarettes during their youth compared to heterosexual women and that this difference in consumption is associated with discrimination and violence. Another study found that, for these women, suicidal ideation is directly correlated with discrimination and violence (Ortíz-Hernández, 2005). Considering that there is a dearth of knowledge on LBW's mental health, this paper aims to contribute to research in this field by describing the association between internalized homonegativity, community connectedness, and discrimination and violence based on homonegativity by using, with indicators of depression and alcohol use. We were particularly interested in understanding how these two mental health indicators were affected by three forms of stigma (homonegative discrimination, homonegative violence, and internalized homonegativity) as well as by community connectedness.

Method

Previous data led us to the objective of analyzing the relationship between community connectedness, internalized homonegativity, and homonegative discrimination and violence with two main mental health indicators: depression and alcohol use. Our hypothesis are that (1) depression and alcohol use (coded as dependent variables) are dependent on internalized homonegativity, community connectedness, and homonegative discrimination and violence (coded as independent variables); and (2) lesbians and bisexual women will score differently on both independent and dependent variables.

Participants and procedure

This study is part of a larger research project that aimed to understand LGBT experiences regarding homophobic and transphobic discrimination and violence and the connection to mental health outcomes, internalized homonegativity, and community connectedness. Participants were asked to participate during Mexico City's Sexual Diversity and Pride March, which took place in June 2015. They were then asked to complete a paper version of the questionnaire as part of a face-to-face interview (between 30 and 40 minutes) (N=277, 98 bisexuals and 138 lesbians), which was conducted by an educational psychology major student studying at a Mexican University. Students had to undertake a four-hour training session that was specific to the needs of this research, have previous experience in recruitment and data collection, and were compensated for their work. An online sample was also used to answer a digital version of the same questionnaire that was available on the Survey Monkey platform (Waclawski, 2012) from June to August 2015 (N=653, 219 bisexuals and 365 lesbians). The online survey was advertised on Facebook, Twitter, as well on non-profit and governmental office websites.

From this sample, 553 participants did not answer at least one variable of interest, which meant that they were then excluded from further analysis. The amount of missing data can be explained by the fact that the main project included a very large number of variables that were collected from participants. Of the 377 participants, 10 identified as asexual, queer or pansexual and were, thus, also excluded from further analysis. We conducted T student analysis to identify differences between the face-to-face and online participants, but no statistical differences were found in any of the measurements. Table 1 shows participants' main sociodemographic variables. Participants were mostly young, educated, single, middle-class atheists.

Survey Instruments

Internalized homonegativity: the Internalized Homophobia Scale (Herek, Cogan, Gillis, & Glunt, 1998) was adapted from the original English version into Spanish using a double-blind translation method (Lozano-Verduzco & Salinas-Quiroz, 2016). It is composed of 12 items on a five-point Likert scale that explores the respondents' negative believes about their own non-heterosexual sexuality and is organized into two dimensions. For the first, statistical analyses, show an internal reliability of 0.874 and an explained variance of 57.8%. The first dimension named "acceptance of heterosexuality" is composed of eight items answered on a 5-point Likert-type scale from 1 (completely disagree) to 5 (completely disagree) that refer to the participants' desire and approval of heterosexual relationships (i.e. "I was I was no longer homosexual, bisexual, or trans-gender"), with α = .873. The second dimension, "fear of social rejection", is composed of four 5-point Likert-type scale from 1 (completely disagree) to 5 (completely agree) items that refer to the participants' worry of being rejected in different social situations because of their lesbian or bisexual identity and practices (i.e. "I am afraid my family will reject me"), with α = .774. Higher scores indicated higher levels of internalized homonegativity.

Community connectedness: Frost and Meyer's (2012) questionnaire was also translated into Spanish using a double-blind translation method (Lozano-Verduzco & Salinas-Quiroz, 2016). This scale had a 0.896 internal consistency and a 58.7% explained variance; it is composed of eight items listed on a Likert scale (1=completely disagree to 5=completely agree) that explore the closeness the respondent feels to their community in a single dimension (i.e. "you feel you are part of the LGBT community in Mexico City"). Higher scores indicate higher levels of connectedness.

Depression: this scale was built using nine items from the General Health Questionnaire originally developed and validated by Romero and Medina-Mora (1987) and later adapted and validated for the Mexican lesbian, gay, and bisexual population by Ortíz-Hernández (2005). It explores feelings of discomfort such as having low energy and crying (i.e. "have you felt exhausted?"), as well as levels of activity and wellbeing (i.e. "have you felt happy?") during the previous month, and used a 5-point Likert-type scale that ranged from 1 (never) to 5 (always). Items pertaining to activity and wellbeing were recoded; higher scores on all items would indicate higher levels of depression (α=.729).

Alcohol use: six questions from the Alcohol Use Disorder Test (AUDIT, Babor, Higgins-Biddle, Saunders, & Monteiro, 2001) were chosen based on Ortíz-Hernández's (2005) use with lesbian, gay, and bisexual Mexican participants. This scale was divided into two theoretical dimensions: frequency and quantity of alcohol consumption ('alcohol', with items such as "how frequently do you drink more than 6 glasses in one sitting?") and was composed of three items answered on a 5-point Likert-type scale (0=never; 4=daily or almost daily; α=.446). It also included problems related to alcohol use ('problems with alcohol', as well as items such as "have you ever felt bad, guilty, or remorseful because of the way you drink?") and was made up of four "yes" or "no" questions (α=.908).

Discrimination and violence: Questionnaires designed by Brito et al. (2012) were used. The discrimination (α= .623) questionnaire is composed of 15 "yes" or "no" questions that explore if basic human rights and liberties have been threatened in different private and public spaces. This scale includes items such as "have you ever been denied a healthcare service?" The violence questionnaire (α=.583) is composed of eight "yes" or "no" questions that explore if the respondent's physical and psychological integrity has been harmed (i.e. "have you ever been physically assaulted because of your sexual orientation and/or gender identity?"). For these two questionnaires "yes" answers were coded as 2, and "no" as 1, which were then added to obtain a total. For the discrimination questionnaire, any number between 16 and 30 indicates that there has been discrimination (high scores indicate higher frequency of discrimination in different spaces). For the violence questionnaire, any number between 9 and 16 indicate that violence has taken place (higher scores indicate higher frequency of violence).

Socioeconomic status: the survey included a reliable instrument to assess socio-economic status that was developed by the Mexican Association of Market Intelligence and Opinion (AMAI). The instrument consists of eight questions that can be organized into three socioeconomic levels (see Table 1). This section of the questionnaire included questions such as "how many rooms are in your home?" that evaluate dimensions such as housing, level of education, and access to technology and health, and it was only used for descriptive purposes.

Analysis

All data was analyzed using the Statistical Package for Social Research version 24. Software was used to carry out frequencies, the Pearson Correlation, Student's t-distribution, and linear regression models. Pearson correlations between variables of interest showed to be mostly significant, and varied in strength, from medium (from .3 to .6) to high (above 0.6). We also analyzed the differences between averages using Student's t-distribution tests. Results showed significant differences between lesbian and bisexual women, thus hypothesis two was confirmed; we then carried out analysis separately for lesbians and bisexuals. Such correlations were shown to be of sufficient strength to justify carrying out linear regression models to predict dependent variables of interest: depression and alcohol use as indicators of mental health. We also carried out specific models for each subgroup. The sample for which the regression analysis was conducted is smaller than the one described above because the combination of variables produced more missing values. Due to this final sample size, we did not carry out a mediating analysis.

Ethical considerations

The first page of both versions of the survey included a consent form that briefly described the objectives of the research project, identified the research team and affiliations, and guaranteed anonymous, voluntary, and confidential participation. No compensation was offered. The Research Committee (IRB) at the National Pedagogic University approved the project in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, subsequent amendments, and local laws. We considered the possibility of including participants under 18 years without parental consent as this research poses a minimal-risk. Furthermore, Mustanski (2011) demonstrates that requiring parental consent for LGBT minors alters research results because risks become greater than benefits. Research shows that asking for parental consent when researching LBW individuals under the age of 18 places the minors at a greater risk and creates an important void in knowledge in terms of their mental health, which increases health disparities for these individuals (Fisher & Mustanski, 2014).

Results

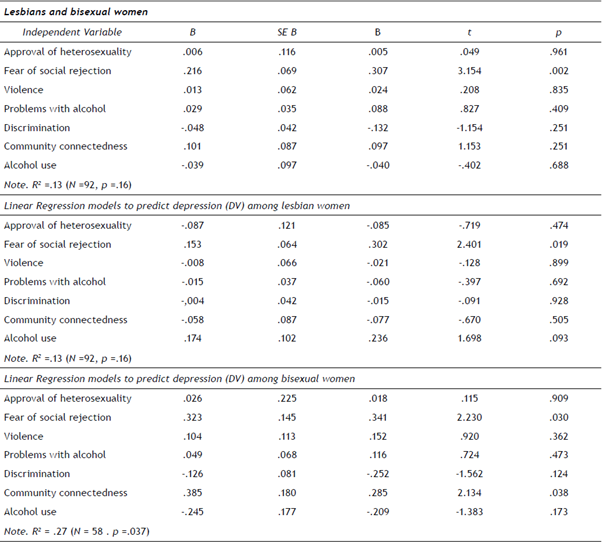

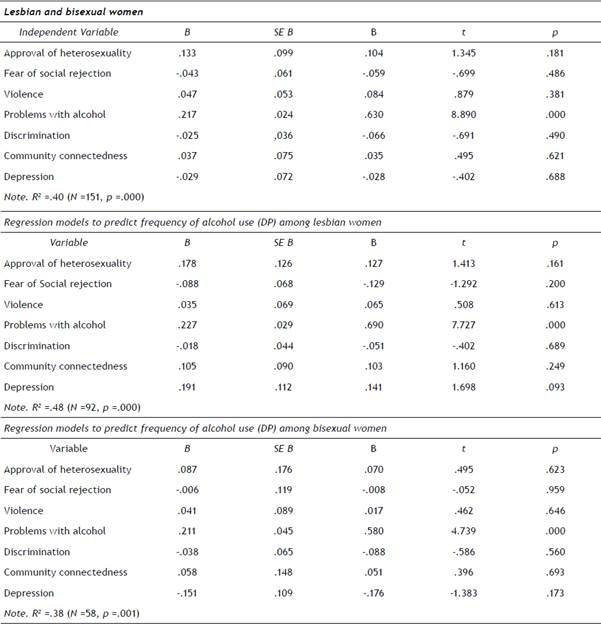

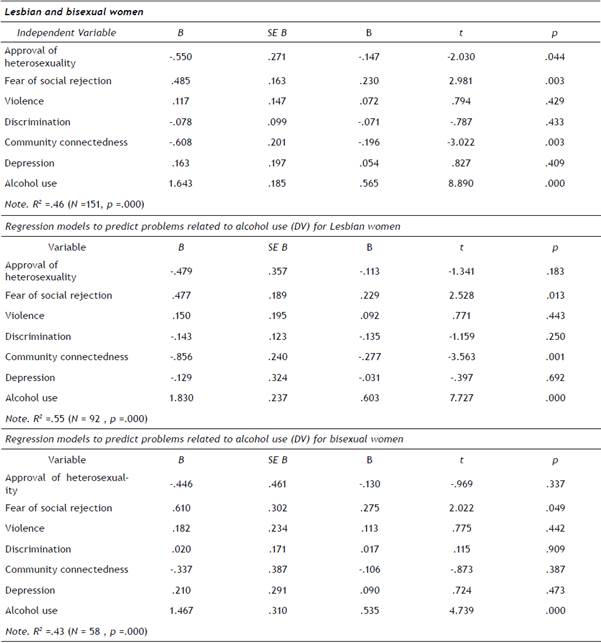

Tables two to four show nine linear regression models that predict one indicator for each of the mental health indicators: depression, alcohol use, and problems with alcohol use. Each table shows a regression model for the whole sample: one for lesbians and one for bisexual women.

Table 4 Regression models to predict problems related to alcohol use (DV) for Lesbian and bisexual women

Models regarding alcohol use and having problems with alcohol proved significant; they indicate that the interaction between independent variables contributes to predicting problems related to alcohol use and frequency of alcohol use. Only the predictive model for bisexual women was significant for depression.

Discussion

In general, participants show that they are comfortable with their homosexuality but fear social rejection because of their non-heterosexual identity. Thus, they join LBW groups where they can develop important mechanisms to help them cope with rejection and fear, such as support networks, positive role models to build a strong sense of identity, self-worth, and purpose. The formation of these groups aim to provide friendship, a sense of community, and, thus, strengthen local forms of identification (Jetten, Postmes, & Haslam, 2009). However, higher levels of community connectedness go together with increased alcohol consumption as spaces that cater specifically to LBW are bars and restaurants where alcohol is sold (ENCODAT, 2017).

Regression models show that fear of social rejection and community connectedness are relevant for the mental health indicators we evaluate, and that discrimination and violence are not related to mental health outcomes. Hatzenbuehler et al. (2009) showed that experiences of minority stigma and stress are not always related to an actual event involving violence or discrimination but instead to the rumination and suppression of the emotions produced by the discriminatory or violent event. This evidence is supported by Mendoza and Ortiz's (2018) findings, which show that homonegative violence acts as a mediating variable in mental health disparities among gay, lesbian, and bisexual Mexican youth. The present data seems to suggest that mental health outcomes are related to the psychological consequences of acts of discrimination, violence and internalized homonegativity (such as rumination, stress, and fear) rather than to actual events of discrimination and violence.

The little previous research shows conflicting results Ortíz-Hernández (2005) reported a direct correlation between mental health outcomes and experiences of discrimination, something that is not considered by this dataset, while Mendoza and Ortiz (2018) found discrimination and violence to be a mediating variable. Despite the fact we did not carry out a mediating analysis, the lack of a relationship between discrimination, violence, and mental health suggests that the latter do mediate the former variables. Further research on LBW that considers a wider and more diverse sample would be beneficial to understand the different social conditions that affect their mental wellbeing.

In two models, community connectedness proved to negatively corelate with mental health, which indicated that women who tend to have a stronger connection with other LBW are likely to present lower levels of depression and alcohol use/problems. This confirms that being part of a peer group is useful to create coping mechanisms to face homonegativity. Community connectedness seems to constitute a space where emotions such as fear are dissipated and maybe solved through a sense of groupness. Thus, women constructing community is a factor that protects against depression, alcohol use, and other problems.

A surprising result for bisexuals was that depression positively correlates with community connectedness: higher levels of depression indicate higher levels of this connection. This tendency was not found among lesbian participants. It may be that bisexual women are not completely comfortable among other lesbian, bisexual, and gay groups, and thus, their experiences of disconnection lead to negative outcomes for their health. Bisexual women who do not feel close to their peers also miss out on the possibility of developing coping mechanisms to adequately face forms of homonegative stigma. For bisexual women, there are also associations between mental health issues, fear of social rejection, and community connectedness: something that is not present among lesbian participants. Previous research shows that bisexuals may experience social pressure to either adjust to a heterosexual or homosexual identity, which is a pressure that is negatively associated with psychological wellbeing, even after controlling for internalized stigma (Balsam & Mohr, 2007; Diamond, 2008; Mohr & Kendra, 2011; Talley & Stevens, 2015; Thompson & Morgan, 2008). Bisexuals in this sample may be experiencing such pressure that is expressed in lower levels of community connectedness, which is also associated with mental health indicators, particularly problems related to alcohol use. In this sense, bisexual women may experience forms of exclusion from heterosexuals and from the lesbian community that has an effect on beliefs about their own sexuality and is expressed by higher levels of internalized homonegativity.

Conclusions

Despite legal changes that support human rights for sexual minorities, including lesbians and bisexuals, health issues still prevail, and a consistent agenda to address them must be put in place by local and federal authorities as well as by activist groups. These legal changes are not sufficient to combat the stress experienced by lesbians and bisexuals because they do not translate into social changes: inclusion, respect, and acceptance of sexual diversity. Furthermore, further research regarding LBW coping mechanisms would be beneficial to be able to understand their cognitive and emotional processes when confronting stigma.

Data in this paper also shows that while external expressions of homonegativity are not related to health outcomes, internalized forms of negative beliefs about homosexuality are. Negative beliefs about an individual's non-heterosexual preference must be viewed contextually and show that within societies that endorse systems and institutions that privilege heterosexuality and oppress other forms of sexual expression, homosexuality will continue to be seen as negative and socially undesirable. Interactions and dynamics based on these precepts make it easier for individuals to incorporate such notions into a sense of self and understanding of the world.

As a whole, this paper provides an understanding about the importance of continuing intersectional research that can help build articulated forms of studying sexual minorities. This is necessary because of the multiple forms of vulnerability, stress, and stigma that LBW face. Further research with LBW in Mexico must contemplate their minority status as non-heterosexual women, their gender expressions, socio-economic levels, age cohort, and the interactions between these variables. However, most importantly, there must be precise measurements of the different expressions of homonegativity within large probabilistic samples. Lastly, future research would be useful to help influence future policy in health services, to show that there is an important need for health services that cater for minorities, and to aid action that will reduce stigma based on homonegativity.

Limitations

We must accept the limitations of the data presented in this research: the small, purposive sample, which included a young, middle-class, and educated group of participants. The sample size is also a result of the still-growing visibilization of the Mexican LGBT community, particularly that of LBW. The cultural dynamics explained in this paper provide evidence of the stigma surrounding these women. However, there is no current research regarding LBW's health in Mexico, so the data in this paper can be understood as an actualization of contemporary lesbian and bisexual women's descriptions of their mental health and experiences regarding homonegativity.