Introduction

Eating habits are framed within a social environment. Research has shown that eating habits are mainly instilled by the family environment and parental behaviours from childhood (Garrido-Fernández et al., 2020; Schnettler, Lobos et al., 2017; Utter et al., 2018). This family influence plays a crucial role in how food is intertwined, not only with a person’s health, but also with their social life. The construct of Satisfaction with Food-related Life ( SWFoL, Grunert et al., 2007) thus encompasses the importance that food has for a person’s health and social relations; the time, energy and financial resources invested in eating and food-related tasks, and the impact that availability and consumption has on overall life satisfaction and subjective well-being (Lamu & Olsen, 2018; Salvy et al., 2017; Schnettler et al., 2021; Schnettler, Hueche et al., 2020; Scott & Vallen, 2019). In general terms, SWFoL is defined as an individual’s overall assessment of their food and eating habits (Grunert et al., 2007).

High satisfaction with food-related life has been associated with high life satisfaction in adults and adolescents (Liu & Grunert, 2019; Schnettler, Grunert et al., 2018a; Schnettler, Lobos et al., 2017; Schnettler, Miranda-Zapata et al., 2020a). Healthy eating habits including frequent family meals, fruit and vegetable consumption, positive attitude when eating with others, less obesity, and fewer eating disorders (Martin-Biggers et al., 2018; Utter et al., 2018; Watts et al., 2017) have been associated with higher levels of satisfaction with food-related life in adults and adolescents (Liu & Grunert, 2019; Schnettler, Lobos et al., 2017; Schnettler, Grunert et al., 2018a; Schnettler, Grunert et al., 2018b).

Satisfaction with food-related life has also been related to the work and family domains, particularly in women. In the last decades, women have increasingly joined the workforce, both in developed and developing countries, which has entailed a shift in conventional family functioning and eating habits (Schnettler, Miranda-Zapata et al., 2018). Women’s working hours outside the home have been found to influence the health behaviours of herself and her male partner or spouse, which subsequently has an impact on the whole family (Fan et al., 2015; Liu et al., 2017). Healthy eating habits and satisfaction with food-related life can also decrease for different-sex dual-earner parents with an inadequate work-life balance (Schnettler, Miranda-Zapata et al., 2018; Schnettler, Miranda-Zapata et al., Utter ). In addition, the literature shows that mental health problems may decrease the diet quality and the levels of satisfaction with food-related life (Fan et al., 2015; Schnettler et al., 2019). In turn, lower diet quality and lower satisfaction with food-related life are associated with financial difficulties (Schnettler, Miranda et al., 2015; Schnettler, Grunert et al., 2018a; Schnettler, Hueche et al., 2020).

Notwithstanding, questions remain about the role of satisfaction with food-related life in the family environment. Most of the aforementioned studies have used a variable-centred approach to examine relationships between satisfaction with food-related life and related variables. In contrast, a person-centred approach allows to identify differences among people, categorizing them as distinct groups that are internally homogeneous (Bourdier et al., 2018). Some studies have shown the heterogeneity of satisfaction with food-related life among adults (Liu & Grunert, 2019; Schnettler, Denegri et al., 2015; Schnettler, Miranda et al., 2015), and in mother-adolescent dyads (Schnettler, Grunert et al., 2018b). The fathers’ growing involvement in family food practices (Schnettler, Lobos et al., 2017) and childcare (Rhodes et al., 2016; Sharif et al., 2017) have been less investigated.

Examining the levels of satisfaction with food-related life of different family members at the same time can help expand the scope to understand the diverse influences between families. Therefore, this study adopts a triadic focus, centring on mothers, fathers, and adolescents. This triadic approach is supported by the Family Systems Theory (Kerr & Bowen, 1988), which posits that individuals in a family are interdependent on one another. This study also relies on crossover processes, that is, the transmission of experiences and related emotions between individuals who live in the same environment (Bakker & Demerouti, 2013).

Research has shown that a greater balance between work and family in parents is associated with providing healthier food, and more frequent family meals (Agrawal et al., 2018; Garrido-Fernández et al., 2020; Liu et al., 2017). For dual-earner couples, the stress of having a full-time job can mean that they are less able to provide healthy food, instead inducing their children to eat more fast food (Fan et al., 2015; Garrido-Fernández et al., 2020; Liu et al., 2017). Both parents’ work-life balance has also been linked to their adolescent children’s satisfaction with food-related life (Schnettler, Miranda-Zapata et al., 2018), and to their own satisfaction with food-related life (Schnettler, Miranda-Zapata et al., 2020b). Thus, it can be expected that one parent’s level of work-life balance influences the level of satisfaction with food-related life in the other parent and their children (Schnettler, Miranda-Zapata et al., 2018; Schnettler, Miranda-Zapata et al., 2020b).

A working individual’s well-being can also be enhanced through a well-functioning family (Botha et al., 2018). The construct of family functioning (Botha et al., 2018) comprises family interactions and relationships based on conflict, cohesion, adaptability, organization, and communication (Alderfer et al., 2007); this construct has shown a positive correlation with adults’ and adolescents’ life satisfaction (Botha et al., 2018; Zhou et al., 2018). In the food domain, it has been reported that a well-functioning family has more recurrent family meals (Pedersen et al., 2016; Utter et al., 2018), leading to greater satisfaction with food-related life in children and adults (Schnettler, Miranda-Zapata et al., 2018; Schnettler, Grunert et al., 2018a; Schnettler, Grunert et al., 2018b; Schnettler, Lobos et al., 2017; Schnettler et al., 2019). Other studies have shown that high levels of family functioning are related to healthier food served during family meals (Castejón & Berengüí, 2020; Pratt & Skelton, 2018) and to adolescent boys and girls having lower body mass indexes, consuming healthier food and breakfasts, and eating more often with their families (Berge et al., 2013; Pratt & Skelton, 2018). Thus, it can be expected that better family functioning perceived by each family member positively influences the level of satisfaction with food-related life for all of them.

Another psychological aspect known to influence family members’ satisfaction in the food domain is the parents’ mental health (Fan et al., 2015; Schnettler et al., 2019). Mental health issues have been related to unhealthy eating habits and less frequent family meals in parents and their children (Dimov et al., 2019; Horodynski et al., 2018; Levin & Kirby, 2012), which in turn have been associated with lower satisfaction with food-related life in adult and adolescent samples (Castejón & Berengüí, 2020; Schnettler, Lobos et al., 2017). Parents coping with depression, stress or anxiety often pay less attention to, and thus alter the nature of, the food provided during family meals (Castejón & Berengüí, 2020). Depressive symptoms negatively modify parental behaviours, so that commitment, family communication, and bonding become difficult (Castejón & Berengüí, 2020; Levin & Kirby, 2012). One study negatively associated depression with satisfaction with food-related life in dual earner-parents (Schnettler et al., 2019), suggesting that mental health status can influence satisfaction with food-related life in parents and children.

Satisfaction with food-related life can also differ based on sociodemographic characteristics. Low socioeconomic status, income, or a poor household financial situation impacts the family capacity to buy healthy food, thus leading to lower levels of satisfaction with food-related life (Schnettler, Grunert et al., 2018a; Schnettler, Hueche et al., 2020 Schnettler, Miranda et al., 2015). In addition, satisfaction with food-related life has been associated with gender (Schnettler, Hueche et al., 2020; Schnettler, Miranda et al., 2017) and age (Schnettler, Grunert et al., 2018b; Schnettler, Hueche et al., 2020 Schnettler, Miranda, et al., 2017).

Hence, the aims of the present study were: (i) to identify different family profiles according to their level of satisfaction with their food-related life in a sample of dual-earner families with at least one adolescent child and, (ii) to assess if these profiles differ according to the perceived family functioning of all three family members, the parents’ work-life balance and mental health, and sociodemographic characteristics.

Therefore, using a person-centred approach through a hierarchical cluster analysis, different levels of satisfaction with food-related life can be characterized while accounting for associated conditions in the family, work, and health domains. For this study, the family domain comprises family functioning, socioeconomic status, and perceived financial situation of the household; while the work domain comprises both parents’ WLB; and the health domain, the parent’s levels of depression, anxiety, and stress. Family profiles were built in terms of three family members’ assessment of satisfaction with food-related life (i.e., satisfaction with food-related life scores), classifying mother, father, and one adolescent child as families based on their levels of satisfaction with food-related life. Subsequently, related variables to the family, work, and health domains were explored in order to identify the differences among family profiles.

The following hypotheses were proposed:

H1. Family profiles can be identified based on the mother’s, father’s, and adolescent’s scores on the Satisfaction with Food-related Life Scale.

H2. Mother, fathers, and adolescents from family typologies with higher levels of satisfaction with food-related life will have significantly higher levels of family functioning.

H3. Parents from family typologies with higher levels of satisfaction with food-related life will have higher levels of work-life balance.

H4. Parents from family typologies with higher levels of satisfaction with food-related life will have lower levels of depression, anxiety, and stress.

H5. Parents from family typologies with higher levels of satisfaction with food-related life will have more positive perceptions of the family’s financial situation.

H6. Family typologies will differ in their sociodemographic characteristics.

The present study makes a two-fold contribution to exploring the heterogeneity of satisfaction with food-related life among individuals and families. First, this study expands on the viewpoints of individuals or mother-adolescent dyads, examining the latter and incorporating the father’s food-related experiences. The second contribution of this study is identifying variables related to the family, work and health domains, that can be linked to mothers’, fathers’ and adolescents’ satisfaction with food-related life in different-sex dual-earner households, beyond nutritional intake and eating behaviours.

Method

Sample

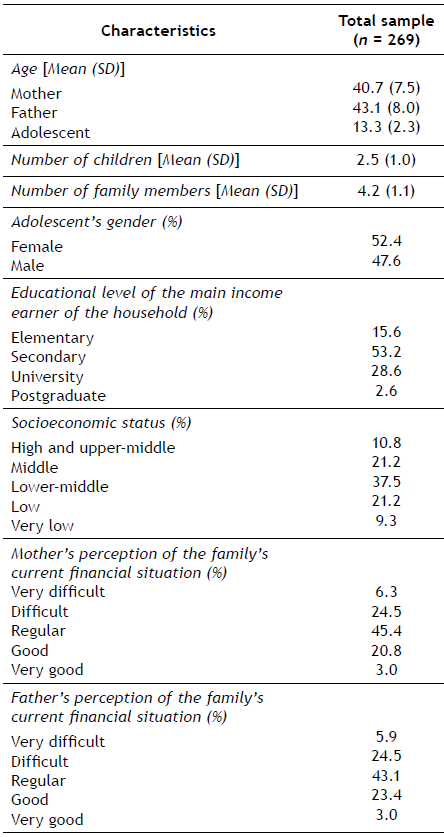

The sample of this cross-sectional study consisted of 269 dual-earner families with at least one adolescent child between 10 and 17 years old. Participants were enrolled via non-probability sampling in Temuco, Chile, and recruited from seven schools that serve socioeconomically diverse populations. Parents were contacted by trained interviewers who explained the objectives and procedure of the study, and the confidential treatment of the information obtained. Subsequently, both parents and one of their children between 10 and 17 years of age were asked whether they wanted to participate in the study. Table 1 shows the sociodemographic characteristics of the sample. This study is part of a larger study on subjective well-being and food-related life, and it was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Universidad de la Frontera.

Measures

The following instruments were answered by the mother, father and adolescent:

Satisfaction with Food-related Life (SWFoL, Grunert et al., 2007). This scale contains one dimension with five items (e.g., “food and meals are positive elements”). The respondent was asked to indicate the level of agreement with the statements on a 6-point Likert scale. The final SWFoL score resulted in the sum of all five items, where a higher score represented a higher satisfaction with foodrelated life. A validated Spanish version of this scale was used in this study (Schnettler et al., 2011), which has shown good internal consistency in Chilean adult and adolescent samples (Schnettler, Grunert et al., 2018a; Schnettler, Grunert et al., 2018b; Schnettler, Lobos et al., 2017; Schnettler, Miranda Zapata et al., 2018). In the present study, the SWFoL showed adequate internal consistency (Cronbach’s 𝛼 mothers = .893, Cronbach’s 𝛼 fathers = .818, Cronbach’s 𝛼 adolescents = .869).

The Family Adaptation, Partnership, Growth, Affection and Resolve Scale (Family APGAR, Smilkstein, 1978). Family functioning was evaluated through this five-item scale. The scores of each item are summed up to obtain the Family APGAR score (Smilkstein et al., 1982). The Spanish version was used (Bellón et al., 1996), which has shown good reliability in adolescents (Moreno & Londoño-Përez, 2017) and adequate reliability in Latin American adults (Gómez & Ponce, 2010). In this study, the Family APGAR’s internal consistency was acceptable for mothers (Cronbach’s 𝛼 = .687) and adolescents (Cronbach’s 𝛼 = .628), and good for fathers (Cronbach’s 𝛼 = .787).

The following instruments were answered by mothers and fathers:

Work-Life Balance (WLB, Haar, 2013). This three-item scale covers one dimension (e.g., “I manage to balance the demands of my work and personal/family life well”). Participants indicated their degree of agreement with the three statements using a 5-point Likert scale. The final score was the sum of the three items. The Spanish version of the WLB scale was used (Schnettler, Miranda-Zapata et al., 2018), having displayed good internal consistency in international studies (Haar et al., 2014). In the present study, the WLB scale showed good internal consistency for mothers (Cronbach’s 𝛼 = .809) and fathers (Cronbach’s 𝛼 = .875).

Depression, Anxiety and Stress Scale (DASS-21, Lovibond & Lovibond, 1995). The DASS-21 measures depression (e.g., “I could not seem to experience any positive feeling”), anxiety (e.g., “I was aware of dryness of my mouth”) and stress (e.g., “I found it hard to wind down”), using 21 items divided into the three corresponding sub-scales. Participants indicated the frequency in which they experienced these symptoms in the past using a 4-point Likert scale. The sub-scale scores are the sum of their respective items. The scale was used in its Spanish version (Antúnez & Vinet, 2012), which has shown good reliability in Chile (Antúnez & Vinet, 2012; Román et al., 2014). In this study, each sub-scale showed good reliability for mothers (Cronbach’s 𝛼 stress = .867, Cronbach’s 𝛼 depression = .890, Cronbach’s 𝛼 anxiety = .882) and fathers (Cronbach’s 𝛼 stress = .878, Cronbach’s 𝛼 depression = .769, Cronbach’s 𝛼 anxiety = .907).

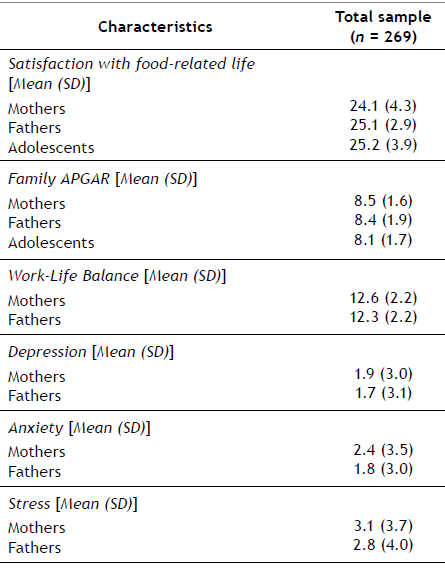

Table 2 shows the mean scores of SWFoL and family functioning scales of the three family members, as well as the work-life balance, depression, anxiety and stress average scores in mothers and fathers.

Table 2 Sample characteristics in terms of satisfaction with food-related life in mothers, fathers and adolescents, their family APGAR and the work-life balance, depression, anxiety and stress in mothers and fathers

Questions regarding sociodemographic characteristics were also included in the questionnaire, such as the age of the participants, the number of children and family members, and gender of the participating child. Occupation and educational level of the head of the household was used to obtain the socioeconomic status (Adimark, 2004). Lastly, both parents were asked to rate their perception of the financial situation of the household.

Procedure

Questionnaires were applied by trained interviewers in the participants’ homes. Both parents signed written informed consent forms, and their adolescent child signed an assent form. Interviews were conducted individually, without the presence of the rest of the family members. This study was conducted between May and August 2017.

Data analysis

Family typologies were identified using a hierarchical cluster analysis using the SWFoL scores of all three interviewed family members. This analysis used squared Euclidean distances and Ward’s method as the grouping method.

The recomposed conglomeration coefficients and the change in their percentage were used to determine the number of clusters (Hair et al., 2007).

After the three family members were grouped into the three typologies based on their SWFoL scores, to identify the differences among family profiles, Pearson’s Chi2 and the Crosstab procedure were used for all discrete variables. An analysis of variance was applied to all continuous variables. The Levene statistic, combined with the analysis of variance, indicated which post hoc test should be administered. Dunnett’s T3 multiple comparisons test was applied to non-homogeneous variances for significant results in the analysis of variance (Levene’s p ≤ .05). Homogeneous variances were carried out by Tukey’s multiple comparisons test (Levene’s p ≥ .05). All data was analysed with SPSS v. 25.0 (IBM Corp. IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Armonk, NY, USA).

Results

Typologies of families according to their satisfaction with food-related life

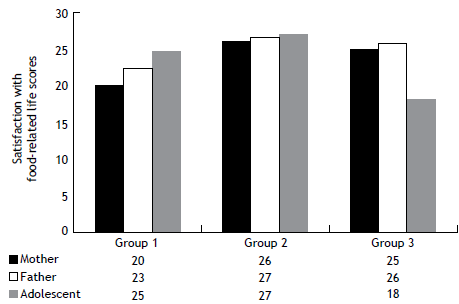

A cluster analysis distinguished three groups of families with statistically different average scores on the Satisfaction with Food-Related Life scale (Figure 1). Group 1 (32.7%) had significantly lower average SWFoL scores than members in Group 2 (p < .001). No significant differences were found for mothers and fathers in Groups 2 (55.0%) and 3 (12.3%), whereas adolescents in Group 3 differed from adolescents in Groups 1 and 2, showing the lowest average SWFoL score in the sample (p < .001).

Figure 1 Family typologies based on satisfaction with food-related life in mother-father-adolescent triads

Mother’s and adolescent’s scores for the Satisfaction with Foodrelated Life Scale were subjected to Dunnett’s T3 multiple comparisons test.

Father’s scores for the Satisfaction with Food-related Life Scale were subjected to Tukey’s multiple comparisons test.

The first hypothesis of this study stated that mother-father-adolescent families can be identified based on their SWFoL scores. This hypothesis was supported, as family typologies were labelled on the basis of the cut-off points for the SWFoL scores used by previous studies, which wereranked as follows: 5-10 = Extremely unsatisfied, 11-15 = Unsatisfied, 16-20 = Moderately satisfied, 21-25 = Satisfied, 26-30 = Extremely satisfied (Schnettler, Höger et al., 2017). Therefore, Group 1 (32.7%) represented “mothers moderately satisfied, and fathers and adolescents satisfied, with their food-related life”. Group 2 (55.0%) comprised “families extremely satisfied with their food-related life”, whereas Group 3 (12.3%) included “mothers and fathers satisfied, and adolescents moderately satisfied, with their food-related life”.

Family, work and health related variables that characterize the family typologies

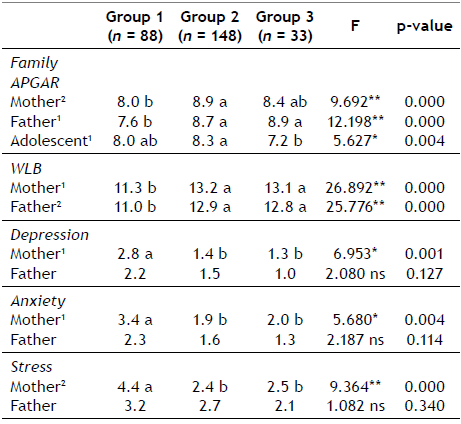

Hypothesis 2 stated that family typologies with higher levels of SWFoL would also report higher levels of family functioning. Results showed that mothers from Group 2 had the highest average scores on the Family APGAR (p < .001), significantly higher than mothers from Group 1, although they did not differ from mothers in Group 3. Fathers in Group 3 had the highest average score on the Family APGAR (p < .001), significantly higher than fathers in Group 1, but did not differ from fathers in Group 2. The adolescents in Group 2 had the highest average scores on the scale (p < .01), significantly higher than adolescents in Group 3, although they did not differ from Group 1. Thus, H2 was supported for mothers and fathers, but not for adolescents.

Hypothesis 3 stated that parents from family typologies with higher SWFoL would also report higher levels of WLB. Both parents in Groups 2 and 3 had significantly higher work-life balance average scores (p < .001) than Group 1 (Table 3), thus supporting H3. Per the fourth hypothesis, it was expected that parents with higher SWFoL would report lower depression, anxiety, and stress levels. Findings showed that mothers in Group 1 had a significantly higher DASS-21 score for the depression sub-scale (p < .01) than mothers in Groups 2 and 3, which did not differ from each other. Mothers in Group 1 also had the highest average anxiety scores (p < .01), significantly higher than mothers in Groups 2 and 3. Regarding the last sub-scale of the DASS21, namely stress, mothers in Group 1 had the highest average score (p < .001), significantly higher than mothers in Groups 2 and 3. The three family profiles did not significantly differ in terms of the fathers’ depression, anxiety and stress (p > 0.1) Thus, H4 was supported for mothers but not for fathers.

Table 3 Differences among the three groups of families according to the perceived family functioning (Family APGAR) in mothers, fathers and adolescents, the work-life balance (WLB), depression, anxiety and stress averages in mothers and fathers

1Different letters on the line indicate significant differences according to Dunnett’s T3 multiple comparisons test.

2Different letters on the line indicate significant differences according to Tukey’s multiple comparisons test.

* Significant at 1%. **Significant at 0,1%. ns = Not significant.

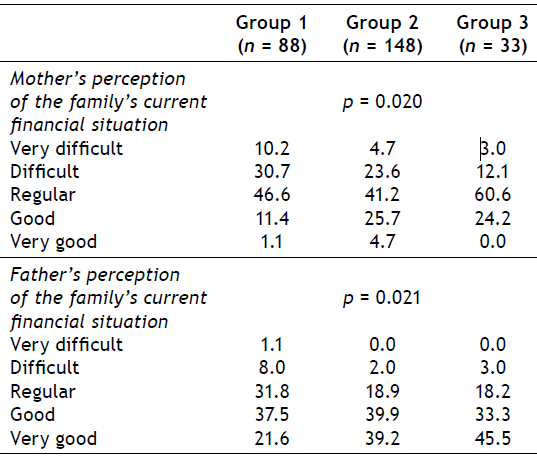

According to hypothesis 5, parents from families with higher SWFoL would have more positive perceptions of their family’s financial situation. In this regard, significant differences among the three family profiles were found in the mothers’ and fathers’ perceptions (Table 4). Group 2 had a greater proportion of mothers who perceived the financial situation of the family as “good” (p < .05). Group 1 had a greater proportion of fathers who perceived the family’s financial situation as “difficult” or “regular” (p < .05). Thus, H5 was partially supported.

Table 4 Differences among the three family profiles according to the mothers’ and fathers’ perception of the family’s current financial situation by (%)

The p-value corresponds to the bilateral asymptotic significance obtained in Pearson’s Chi-squared test.

Lastly, in hypothesis six it was expected that the family typologies would differ in sociodemographic characteristics.

However, results showed that the three family profiles did not significantly differ in terms age of the three family members; number of children and family members; gender of the adolescent respondent; education level of the head of the household; nor socioeconomic status (p > 0.1). These results did not support H6.

Discussion

This study identified family profiles according to parents’ and one adolescent child’s satisfaction with food-related life; and to characterize these profiles according to differences in the parents’ work-life balance and mental health, family functioning, and the family’s sociodemographic characteristics. The cluster analysis based examining these mother-father-adolescent triads distinguished three family profiles. Group 1 (32.7%) represented “mothers moderately satisfied, and fathers and adolescents satisfied, with their food-related life”. Group 2 (55.0%) comprised “families extremely satisfied with their food-related life”, whereas Group 3 (12.3%) included “mothers and fathers satisfied, and adolescents moderately satisfied, with their food-related life”. Group 3 (n = 33) will not be discussed here, as the sample size was too small to allow drawing generalizable conclusions (McEwan, 1997).

The first relevant result is the relationship observed between SWFoL and work-life balance. Parents in Group 1 had a low work-life balance, while Group 2’s mothers and fathers had a high work-life balance. This difference suggests that parents’ adequate work-life balance can enhance the SWFoL of all family members, supporting previous research (Schnettler, Miranda-Zapata et al., 2018), while confirming that SWFoL and work-life balance are related in parents (Schnettler, Miranda-Zapata et al., 2020b). It may be that an inadequate work-life balance in parents decreases their time available for purchasing food and preparing family meals (Garrido-Fernández et al., 2020; Fan et al., 2015; Liu et al., 2017), thus reducing the SWFoL for themselves and other family members (Schnettler, Miranda-Zapata et al., 2018; Schnettler, Miranda-Zapata et al., 2020b). Most studies addressing this influence of work on food-related life has been examined in mother-child dyads, involving fathers less frequently (Fan et al., 2015). The present study contributes to the latter gap by showing that an adequate work-life balance in fathers can also be associated with the SWFoL of other family members. Nevertheless, more research is needed in order to establish the extent to which fathers’ work-life balance influences their family’s SWFoL compared to the mothers’.

Regarding mental health measures, fathers in the family profiles did not differ in depression, anxiety and stress levels. On the other hand, mothers’ mental health seemed to be a determinant for their own SWFoL, partially confirming previous findings in dual-earner couples (Schnettler et al., 2019). Mothers in Group 1 had the highest levels of depression, anxiety and stress, as well as the lowest levels of SWFoL. A possible explanation for this relationship is that an affected mental health relates to decreased cognitive and affective functioning, which in caretakers (e.g. a parent) can diminish their involvement and willingness to provide nutritious meals and healthy food to oneself and one’s family (Castejón & Berengüí, 2020; Dimov et al., 2019).

Nevertheless, the lower levels on the DASS-21 in Group 1 mothers did not seem to influence their partners’ and children’s SWFoL as it was expected. Previous studies have described mothers as the main decision-makers regarding food and diet in a household, and who promote a specific food intake during family meals (Rhodes et al., 2016; Schnettler, Hueche et al., 2020; Schnettler, Lobos et al., 2017). Hence, it might be that a depressed, anxious or very stressed mother would place less importance on healthy eating habits and food because of increased self-preoccupation and psychological coping (Castejón & Berengüí, 2020; Levin & Kirby, 2012). In this study, it was expected that a mother’s decreased mental health would have a negative impact on her own, and her partner’s and children’s SWFoL, but this was not the case. Mothers in Group 2 had significantly lower levels of depression, anxiety and stress, and all three family members had the highest level of SWFoL, in line with previous findings (Rhodes et al., 2016; Schnettler, Lobos et al., 2017; Schnettler, Miranda-Zapata et al., 2019). This result suggests an important link between mothers’ mental health and their SWFoL.

The Group 2 mother-father-adolescent triads reported being extremely satisfied with their food-related life, and also showed the best family functioning. These findings thus support the hypothesis that a better-functioning family entails having more and healthier family meals (Berge et al., 2013; Castejón & Berengüí, 2020; Pedersen et al., 2016; Pratt & Skelton, 2018; Utter et al., 2018) and higher SWFoL in adults and adolescent children (Schnettler, Grunert et al., 2018a; Schnettler, Grunert et al., 2018b; Schnettler, Grunert et al., 2021; Schnettler, Lobos et al., 2017). It might be that the better a family functions, the better all family members communicate with each other, resolve conflicts, and share family moments, such as family meals. This communication allows them to enjoy a positive atmosphere and dialogue during family meals (Martin-Biggers et al., 2018; Utter et al., 2018), which in turn enhances all family members’ satisfaction with food-related life. For parents, a well-functioning family can motivate them to pay attention to their family’s diet and the food they provide their children, relating family affection to satisfaction with their food-related experiences.

Contrary to what was expected, family profiles did not differ in terms of sociodemographic characteristics. However, parents’ perception of their financial situation differed significantly, a finding which supports the importance of financial resources for satisfaction with food-related life (Schnettler, Grunert et al., 2018a; Schnettler, Hueche et al., 2020; Schnettler, Miranda et al., 2015; Scott & Vallen, 2019). Group 1 had a greater proportion of fathers that perceived the financial situation of their family as “difficult” or “regular”, although SWFoL in fathers and adolescents in Group 1 remained higher than that of the mothers. This finding may relate to a concern in women when their husbands or partners express dissatisfaction or difficulty regarding the family’s financial situation, which might signal difficulties to provide adequate food for their children (Schnettler, Miranda et al., 2015). However, this explanation does not account for the mothers’ role as a provider in a dual-earner couple.

Mothers in Group 1 with moderate SWFoL did not report a worse perception of their financial situation compared to the fathers. Some authors have provided evidence that men place less importance to their nutrition and diet than women (Carty et al., 2017; Schnettler, Hueche et al., 2020), and that women encourage healthy diets and eating habits within a household more than men (Rhodes et al., 2016; Schnettler, Hueche et al., 2020). For this reason, even if fathers perceive their financial situation as “difficult” or “regular”, their SWFoL may not be affected by this. In contrast, Group 2 had a high number of mothers who perceived their financial situation as “good” with high levels of SWFoL. An explanation for this result could be that, if mothers perceive their financial situation as “good”, they will be more likely to spend more money on healthy or nutritious food for their family, hence engendering a higher SWFoL in all family members. In this regard, a recent study stressed the importance for women to have access to and the availability of enough healthy food in order to prepare the family meals, which seems to be a key factor for women’s satisfaction with food-related life (Schnettler, Hueche et al., 2020).

The limitations of this study must be considered in order to improve future research. First, generalizing these results is not possible given the local sample of the study, from one city in Chile; data should be gathered in different Latin American contexts. Families were all composed of dual-earner parents with children aged between 10 to 17 years of age, which entails a lack of population representativeness. The number of members and children per family (mean values: 4.2 and 2.5, respectively) were higher than the average for Chilean families (3.1 and 1.3, respectively) (Instituto Nacional de Estadísticas, 2018). Moreover, the sample was relatively homogeneous in terms of age, and single-parent families were not considered. In addition, the sample had a larger proportion of families from middle-middle and lower-middle socioeconomic status, and a lower proportion of families from lower socioeconomic status, compared to the Chilean population (Asociación Investigadores de Mercado, 2018). Future studies should consider families in other stages of life, with a composition similar to the country’s family size and socioeconomic status, and headed by single parents. A second limitation of the study is that its cross-sectional design did not allow for the follow-up of the study’s participants. Further studies should take into account the evolution over time of SWFoL within families and in different family structures. A third limitation is that, although the present study highlighted that fathers have an influence on other family members’ SWFoL, more studies are needed to support or counter these findings. Other limitations relate to the assessments not considered in this study, such as diet quality and frequency of family meals, which may provide a more thorough account of the differences in family profiles and related variables. Future research should examine these and similar relationships in depth. In addition, future research may be improved by the use of other statistical analyses that allow further exploration of the data, for example, to identify the effect of work-life balance, family functioning, mental health problems and the perception of the financial situation of the household on the probability of a family being part of a particular cluster.

Conclusions and implications

This study distinguished three family profiles according to levels of SWFoL, showing that both the mother’s and father’s work-life balance, the mother’s mental health, and the family functioning are related to the family members’ SWFoL. These findings contribute to highlighting new significant variables that can influence SWFoL, which need to be inspected closely and better understood in the future.

These findings suggest the focus for interventions on parents and adolescent children in order to improve their food-related life, and thus their overall life satisfaction. Institutional and workplace campaigns should implement measures to support and enhance employed parents’ work-life balance. Concerning mental health issues, psychological interventions should approach constructive communication mechanisms and family conflict resolution, and the differential effects of depression, anxiety and stress. Campaigns about food and healthy nutrition should promote accessibility to varied food, as well as education aimed at parents and adolescents regarding the link between a balanced diet and overall well-being. Overall, enhancing satisfaction with food-related life requires tailored interventions on eating behaviours, which can improve both health and family relations, and thus overall life satisfaction in working parents with children.