Bribery, fraud, theft, and other dishonest behaviours have transpired in small to large companies all around the world. In a survey compiled by PwC’s Strategy& in 2016 (Karlsson et al., 2017), it was found that the number of CEOs who were dismissed for ethical lapses in companies all around the world increased significantly over the last five years, from 3.9% of all successions from 2007-11 to 5.3% from 2012-16, a 36% increase. In a report released in 2021, Brazil occupied the 94th position in the global ranking of 180 countries in the Corruption Perceptions Index, where a more rearwards position indicates a higher level of corruption perception (Transparency International, 2021).

Social psychology and the traditional managerial approach can be integrated to a behavioural business ethics approach in order to comprehend ethical behaviour (De Cremer & Moore, 2020). This proposition helps explain the antecedents and outcomes of unethical behaviour by evaluating different levels and considering the psychological processes and contextual factors involved in the ethical decision-making process. We define ethical behaviour as the work performance that follows adequate behaviour standards in the business context and conforms to organisational and societal norms (Russell et al., 2017).

Concerning contextual factors, ethical culture emerges as one central construct due to its critical role in enhancing or diminishing unethical acts (Mayer, 2014). The Corporate Ethical Virtues (CEV) model proposed by Kaptein (2008) provides a solid conceptualisation of ethical culture by evaluating virtues that organisations should seek. The CEV Scale assesses those virtues and has shown good psychometric properties in different countries, such as the Netherlands (Kaptein, 2008), the United States (DeBode et al., 2013), Finland (Kangas et al., 2014) and Colombia (Toro-Arias et al., 2022). However, there is no validated version of a Brazilian-Portuguese scale. Thus, this study aimed to adapt and provide evidence of validity of the CEV Scale in the Brazilian context.

The ethical culture construct was derived from the literature concerning organisational culture. In this regard, we adopt the definition of ethical culture put forth by Treviño (1990) as a subset of organisational culture that represents the interplay between formal and informal systems of ethics that influence the employee’s (un)ethical behaviour.

To improve the definition of ethical culture, Kaptein (2008) refined the construct and developed a new scale. He used the Corporate Ethical Virtues (CEV) Model to comprehend the ethical culture of organisations. This model postulates that the virtuosity of an organisation can be determined by the extent to which organisational culture encourages employees to act ethically and prevents them from acting unethically. Kaptein (2008) created a self-report questionnaire to measure the ethical virtues that consisted of 58 items covering seven factors that later became eight factors.

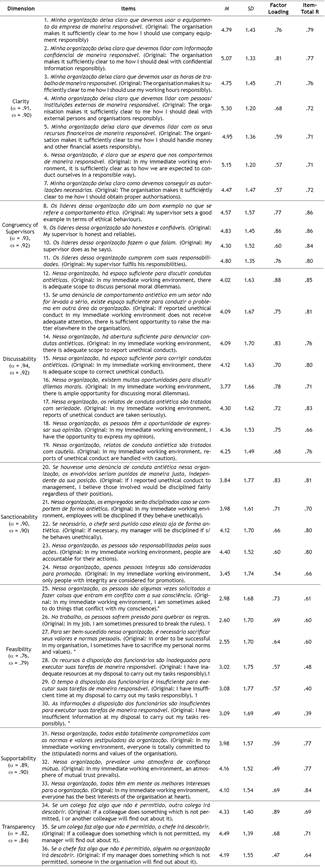

The eight factors representing eight virtues were as follows: 1) Clarity: the extent to which ethical expectations are clear and understandable to employees and managers; 2) Congruency of management: the extent to which top and senior management act according to ethical expectations; 3) Congruency of supervisors: in furtherance of the immediate supervisors acting in accordance with ethical expectations; 4) Discussability: which is concerned with how much managers and employees have the opportunity to discuss ethical issues; 5) Sanctionability: the degree to which managers and employees believe there are rewards and punishments regarding (un)ethical behaviours; 6) Feasibility: to what lengths does the organisation go to provide sufficient equipment, budgets, and autonomy for managers and employees; 7) Supportability: how well does the organisation support ethical expectations between management and staff; and 8) Transparency: the degree to which ethical and unethical conduct is visible to responsible managers and officials (Kaptein, 2008). The exploratory factor analysis (EFA) results indicated that the items regarding the proposed virtue (congruency) incurred into two different factors (later identified as congruency of management and congruency of supervisors).

The original version of the CEV Scale has shown good psychometric properties in samples in the Netherlands (Kaptein, 2008, 2011). It has been translated into different languages and administered in different countries and samples, i.e., the United States (DeBode et al., 2013), Finland (Huhtala et al., 2013, 2016; Kangas et al., 2018), and Lituania (Novelskaite & Pucetaite, 2014). To produce a more accessible version of the scale, other researchers developed a short adaptation of Kaptein’s scale, the CEVMS-SF with 32 items (DeBode et al., 2013). Huhtala et al (2018) investigated its measurement invariance in a Finnish sample with two independent groups.

In reviewing the extant literature on ethical culture, we identified some gaps in its most frequently used measurement - Kaptein’s CEV Scale (2008). The first gap is that the CEV scale -even though it assumes a rearwards process- has items with different referents (such as “my immediate working environment,” “I,” “My supervisor”). However, culture ascertains a shared construct as a property of the work unit or the organisation (Ashkanasy et al., 2011). For instance, a study has demonstrated that various teams within an organisation can have different ethical cultures (Cabana & Kaptein, 2019).

Thus, the literature regarding culture and climate indicates that the referent-shift consensus model is the most appropriate conceptual model for higher-level constructs (Chan, 1998; Klein & Kozlowski, 2000). This means that ethical culture is supposed to be about shared perceptions, and we can infer the existence of a rearwards process. The referent-shift model presumes that there will be an improved consensus of individual responses when items refer to the proper referent (Schneider et al., 2013). Therefore, this study aims to improve the CEV scale by modifying the referents of the items so that all are shifted to the proper higher-level referent, using a referent-shift model.

The second gap is that the CEV scale has been mainly applied in countries where the corruption perception is low and has not been applied in non-WEIRD (Western, Educated, Industrialised, Rich, and Democratic) samples. Even though we have found one recent study with the short version in Colombia (Toro-Arias et al., 2022), the scale is in Spanish, and we adopt the original complete version. Thus, our study aims to contribute by generalising the CEV scale for a non- WEIRD society and for a country where the corruption perception is very high (Transparency International, 2021) - in this case, Brazil in South America.

The third gap is related to the existing overlap in the literature on measures of ethical culture and ethical climate (Mayer, 2014; Treviño et al., 2014), and the claim that no past research has investigated whether ethical culture and ethical climate measures are actually measuring different constructs. The literature on organisational ethics argues that ethical culture differs from ethical climate, even though some researchers may argue that organisational culture and climate are overlapping phenomena (Denison, 1996). Ethical climate encompasses the perceptions regarding the procedures, practices, and behaviours related to ethics. On the other hand, ethical culture is the shared beliefs, values, and norms concerning ethics. Thus, our study endeavours to fill this gap by verifying whether the main measures of ethical climate are empirically distinct from the CEV scale.

Thus, the aims of this study are: 1) to adapt the CEV Scale to a referent-shift model, 2) to provide evidence based on the internal structure and reliability of the Brazilian version of the CEV scale, 3) to provide evidence of discriminant validity with ethical climate, 4) to provide evidence of measurement invariance across different organisations (public vs. private), and 5) to provide evidence of convergent validity with related constructs.

Our research is organised in two studies. In both studies, informed consent was obtained, and participants were ensured that their responses would be confidential and anonymous. Additionally, all the ethical requirements for conducting this type of the study were followed in accord with the Ethical Principles of the American Psychological Association (APA).

Study 1

Method

The CEV Scale (Kaptein, 2008) with 58-items, which measures the ethical culture of organisations, was translated and adapted to Brazilian Portuguese. The guidelines established by the International Test Commission for the translation and adaptation of tests (International Test Comission, 2018) were followed. First, we carried out the back-translation of the original scale with two experts fluent in both languages (English and Brazilian Portuguese).

Next, we changed the referent of all items, adapting them to the organisational level. After the evaluation of experts and professionals who work in organisations, the items that generated ambiguity or misunderstanding were rewritten and improved.

Participants

The sample consisted of 1219 employees from different Brazilian organisations (628 were men, M age = 41.59 years, SD = 13.05). The majority of the participants had at least a bachelor’s degree (n = 871) and worked in public organisations (n = 958).

Measures

Ethical culture. We administered the translated and adapted version of the CEV Scale (Kaptein, 2008) with 58-items to all participants. They responded using a six-cell response format (1 = Strongly Disagree, 6 = Strongly Agree).

Ethical climate. We administered the Ethical Climate within Organisations Scale (Ribeiro et al., 2016) with 19 items on a frequency scale of 1 (completely false) to 6 (completely true). This is a translated and adapted version of the Victor and Cullen (1988) scale. This version of the scale has three dimensions: 1) benevolence (α = .93, ω = .93) with nine items, 2) principles/rules (α = .87, ω = .87) with six items, and 3) independence/instrumental (α = .67, ω = .71) with four items. The CFA for a three-factor model of the scale showed a reasonable fit (χ² = 335.37, df = 149, RMSEA = .09, CFI = .90, TLI = .90, SRMR = .09) with factor loadings ranging from .55 to .89, and all of them were statistically significant (p < .01).

We also administered the Ethical Climate Index (Almeida & Porto, 2019) with 18 items on a 5-point agreement scale, which is a translated and adapted version of the Arnaud (2010) scale. This scale has six factors with three items each: 1) Norms of Moral Awareness (α = .42, ω = .45); 2) Collective Moral Motivation (α = .84, ω = .84); 3) Focus O n Self (α = .85, ω = .86); 4) Norms of Empathetic Concern (α = .64, ω = .74); 5) Focus On Others (α = .80, ω = .81); and 6) Collective Moral Character (α = .67, ω = .70). Despite the first dimension, the others showed a reasonable reliability. Thus, we decided to exclude this dimension from subsequent analysis. The CFA for a five-factor model of the scale showed a reasonable fit (χ² = 771.48, df = 116, RMSEA = .09, CFI = .95, TLI = .94, SRMR = .07), with factor loadings ranging from .47 to .90, and they were statistically significant (p < .01).

Procedures

The questionnaires were applied online using the SurveyMonkey™ tool in different organisations. The Ethical Climate within Organisations Scale was randomly administered to half of the sample and the Ethical Climate Index to the other half, reducing single-source bias. The surveys were disseminated to employees of different Brazilian organisations by means of e-mail and other internal communication tools.

Data Analysis

First, we split our dataset into two random samples to conduct EFA (sample 1a; n = 609) and CFA (sample 1b; n = 610). In the EFA, we used the unweighted least squares (ULS) method of estimation since it is robust against non-normality as it uses as input the sum of the squares of the differences between the observed and reproduced correlation matrixes (Lloret et al., 2017), and used promax oblique rotation.

In sample 1b, the two ethical climate scale items met univariate and multivariate normality assumptions. Considering the lack of normality, we chose the MLR estimation method, which is a method that estimates standard errors and a mean-adjusted chi-square test statistic that is robust to non-normality (Muthén & Muthén, 2012).

To assess the model fit in the CFA, we used the chi-square goodness of fit statistic, the root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA), the comparative fit index (CFI), the Tucker-Lewis index (TLI), and the standardised root mean square residual (SRMR). To compare the models, we evaluated the criterion values of ΔRMSEA, ΔCFI, and ΔTLI. Differences not larger than .015 for ΔRMSEA and differences lower than or equal to .01 for ΔCFI and ΔTLI values are considered an indication of negligible practical differences (Chen, 2007; Cheung & Rensvold, 2002).

Results

We ran an EFA with all original 58 items, using Sample 1a. The Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin (KMO) measure of sampling adequacy was .97, and the Bartlett test of sphericity was statistically significant (p < .01), indicating the suitability of these data for factor analytic procedures. Items with factor loadings lower than .40 and cross-loading items were eliminated. Following these criteria, 13 items were dropped, including all items from the “congruency of management” dimension.

We ran an additional EFA with the 45 remaining items pertaining to seven theoretical ethical virtues. Nine ítems that were not fitting the expected content of their dimension were eliminated; this process resulted in a decision to retain 36 items within seven dimensions. Those items were representative of the seven corporate ethical virtues of the original scale, except for the congruency of management factor. Since items in this version had a referent change, the congruency dimension comprises the evaluation of all leaders of the organisation.

The EFA results are presented on Table 1. The solution with seven factors explained a total variance of 67.1%.

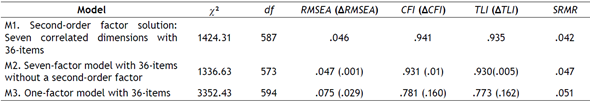

With sample 1b, we performed a second-order CFA in order to obtain additional validity evidence of the internal structure of our version of the CEV Scale. Results indicated that the seven-factor solution with a second-order factor (M1) of ethical culture had an acceptable fit (χ² = 1424.31, df = 587, RMSEA = .05; CFI = .94; TLI = .94; SRMR = .04). Additionally, we tested two alternative models by means of CFA: 1) M2: a seven-factor model with 36-items (without including the second-order factor); and 2) M3: a one-factor solution with 36 items. See Table 2 for the fit indices.

Table 2 CFA Results for the Ethical Culture in Organisations - CEV Scale in Study 1

Note: χ² = chi-square; df = degrees of freedom; RMSEA = root mean square error of approximation; CFI = comparative fit index; TLI = Tucker-Lewis index; SRMR = standardised root mean square residual.

The second-order factor solution with seven correlated dimensions (M1) showed a better fit than the one-factor model (M3). However, there were negligible differences between M1 and M2 (seven-factor model without the second-order factor), which indicated that the two-factor solutions were adequate. Therefore, on account of a theoretical reason, we chose the M1. This result demonstrates validity evidence of the seven-factor model’s internal structure with 36-items of the CEV scale in Brazil.

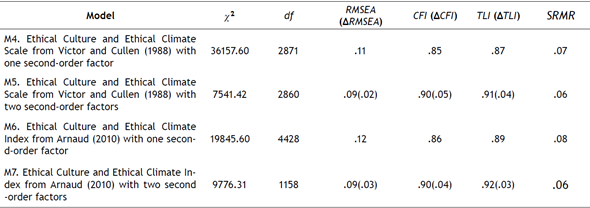

We also aimed to determine the distinctiveness of the ethical culture scale based on different ethical climate measures. We compared four alternative models using CFA with a MLR estimator (Table 3).

Table 3 Discriminant validity between ethical culture (CEV Scale) and ethical climate in Study 1

Notes: χ² = chi-square; df = degrees of freedom; RMSEA = root mean square error of approximation; CFI = comparative fit index; TLI = Tucker-Lewis index; SRMR = standardised root mean square residual.

The models with only one second-order factor (M4 and M6) showed poor fit; whereas, the models with two second-order factors (M5 and M7) showed adequate fit. Additionally, considering the comparative fit indices, M5 showed a non-negligible better fit than M4, and M7 showed a non-negligible better fit than M6. These results provided evidence for the CEV Scale’s distinctiveness based on the ethical climate measures, even though they are highly correlated.

These results provided evidence for the CEV Scale’s distinctiveness based on the ethical climate measures, even though they are highly correlated.

Study 2

Method

Participants

A total of 635 employees from two Brazilian organisations (321 women, M age = 43.09 years, SD = 12.79) participated in this study. Fifty-nine percent of the sample worked in a public information technology company, and 41% worked in different units of a private health organisation. The public company is in the capital of Brazil (with almost 8.000 employees) and the private company is located in the midwest section of the country (with around 400 employees). Almost 70% percent of the sample had at least a college degree. The respondents had worked, on average, for 14.36 years at their current job (SD = 13.15).

Measures

The Brazilian Portuguese version from Study 1 of the CEV Scale with 36-items measuring ethical culture was administered.

Looking for evidence of convergent validity, two instruments measuring unethical behaviour in organisations were used:

Observed Unethical Behaviour in Organisations Scale (MacLean et al., 2015; adapted from Treviño & Weaver, 2001) with seven items. The CFA for the one-factor model of the scale showed a reasonable fit (χ² = 91.63, df = 13, RMSEA = .12, CFI = .95, TLI = .91, SRMR = .04). The reliability coefficients were adequate (α = .87, ω = .90).

Unethical Pro-Organisational Behaviour Scale (Umphress et al., 2010) with six items. The referent was changed from “I” to “Other employees” to reduce social desirability bias (OECD, 2018). The CFA performed to test the one-factor model indicated an acceptable fit to the data (χ² = 48.63, df = 9, RMSEA = .09, CFI = .97, TLI = .96, SRMR = .03). The reliability coefficients were adequate (α = .88, ω = .91).

Data Analysis

CFA was used to examine the factorial validity of the CEV Scale with 36-items from Study 1. The analyses were performed with the Mplus version 7.11, using the MLR estimation method, which is robust to non-normality. Next, multi-group confirmatory factor analysis (MGCFA) with Mplus was used to evaluate the CEV Scale’s measurement invariance in public versus private organisations.

We tested the following three nested models: 1) the configural invariance model, with the same number of factors and the same set of zero factor loadings in all groups; 2) the metric invariance model, in which all factor loadings hold to be equal across groups; and 3) the scalar invariance model, in which all factor loadings and intercepts hold to be equal across groups.

To test measurement invariance, it is expected that as we decrease the number of parameters in each model (configural, metric and scalar), we do not have significant changes in terms of model fit. To verify the nested models’ goodness of fit in the MGCFA measurement invariance models, the incremental fit indices (ΔRMSEA, ΔCFI, and ΔTLI) were compared, using the same criteria described in Study 1.

Results

The CFA with Study 2 sample indicated that the seven-factor solution with 36 items and a second-order factor showed an adequate model fit (χ² = 1351.82, df = 623; RMSEA = .04; CFI = .94; TLI = .93; SRMR = .05). These results further support the seven-factor solution of the adapted and short form of the CEV Scale. The reliability coefficients were satisfactory (α ranged from .78 to .93, and ω from .75 to .93).

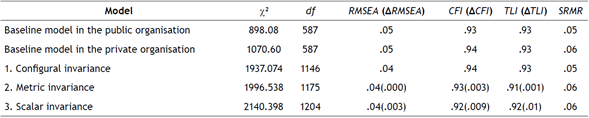

Next, measurement invariance in the private company (n = 378) and the public organisation (n = 257) was tested. Before running the multi-group analysis, we ran two separated CFA (one for each group) and found a reasonable model fit for the model in the private company sample (χ² = 1070.60, df = 587, p < .01; RMSEA = .05; CFI = .94; TLI = .93; SRMR = .06) as well as for the model in the public company sample (χ² = 898.08, df = 587, p < .01; RMSEA = .05; CFI = .93; TLI = .93; SRMR = .05). Subsequently, we proceeded to establish configural, metric and scalar invariance.

The results for the invariance models (Table 4) indicated an acceptable model fit. As the differences in the incremental goodness of fit indices (ΔRMSEA, ΔCFI, and ΔTLI) between the configural invariance model and the successive nested models did not exceed the values applied as criteria, we concluded that configural, metric and scalar invariance were supported. Thus, the Brazilian Portuguese version of the CEV scale showed measurement invariance throughout public and private organisations.

Table 4 Tests of measurement invariance for the CEV Scale in Study 2

Notes: χ² = chi-square; df = degrees of freedom; RMSEA = root mean square error of approximation; CFI = comparative fit index; TLI = Tucker-Lewis index; SRMR = standardised root mean square residual.

Regarding convergent validity, all dimensions of the CEV Scale had a statistically significant negative association with observed unethical behaviour in organisations. For unethical pro-organisational behaviour, five dimensions of ethical culture had a significant negative association, except for the dimensions of feasibility and transparency that did not show significant relationships.

Discussion

The purpose of this study was to demonstrate evidence of validity in Brazil of a translated and adapted version of the Corporate Ethical Virtues Scale that measures ethical culture in organisations. The three main objectives were fulfiled in the two studies presented. We provided evidence based on the internal structure and reliability of the CEV Scale in Brazil, evidenced discriminant validity with two ethical climate measures, confirmed measurement invariance in different organisations (public vs. private), and provided evidence of convergent validity with related constructs. We progressed theoretically by improving the original version of the scale and providing different indices.

Regardless of the remarkable advances made in the measurement of ethical organisational culture, and specifically the Kaptein’s (2008) scale, we sought to expand it to encompass a non-WEIRD society and a country where the perception of corruption is high. We advanced the study of Toro-Arias et al. (2022) by adapting it to Portuguese and using the original CEV version. Hence, our main contribution consists of providing a measure of ethical culture in organisations in the Brazilian context.

The improvement on the scale using a referent-shift model in which all the items now refer to the organisational level enhances its quality by aligning it with the literature on organisational culture. Aside from that, our findings propose an adapted measure in the Brazilian context that managers and consultants can administer in order to evaluate the ethical culture of organisations. The results generated by our studies contribute to organisational ethics literature by providing strong and necessary empirical evidence of construct, discriminant, and convergent validity of the Brazilian version of the scale, as well as measurement invariance.

The seven-factor structure fitted data in both studies with reasonable psychometric quality and distinguished from ethical climate measures. Additionally, our findings provided support for configural, metric, and scalar invariance, indicating no differential ralso negatively correlated with observed unethical behaviour and with unethical pro-organisational behaviour.

Measuring ethical culture is crucial in order to comprehend the ethical context of the organisation and to identify which factors can enhance ethical behaviour. Thus, the Brazilian Portuguese version of the CEV Scale can be used to diagnose objectives in organisations. Consequently, the scale results can be used to improve organisational processes and practices related to ethics management, such as integrity and ethics programmes, codes of ethics, ethics training, etc. In addition, the scale can be used in new research to investigate other constructs related to ethics in the workplace.

Even though this study expands beyond research with a non-WEIRD sample, it is limited in its degree of generalisability. Our scale is mainly adapted for educated populations that work in public and private organisations in Brazil. In addition, we only assessed measurement invariance in two groups (private vs public organisation).

It is uncertain how national culture impacts the perception of ethical organisational culture; thus, more research needs to be done in order to evaluate measurement invariance throughout different countries that speak Portuguese. Consequently, we encourage future research in order to administer this adapted version of the scale and to seek the replication of our results.

In conclusion, our studies advance the comprehension of ethical organisational culture and its most used measurement by refining it and showing evidence of validity in the Brazilian context. The replication and adaptation of scales is a recommended practice that improves the quality of psychological measures (DeBode et al., 2013; Tomás et al., 2014). Thus, these findings suggest that researchers and practitioners can be confident in applying the CEV adapted scale.