Eating Disorders (ED) are a real challenge for public health and healthcare providers (Galmiche et al., 2019), with an estimated prevalence that has ranged from 3.1% to 17.9% among females and 0.6% to 2.4% among males in the DSM-5 era (Silén, & Keski-Rahkonen, 2022). For this reason, current research should pursue not only the study of clinical patterns, but also maladjusted eating behaviour and associated cognitive variables in relation to body image perception, in order to determine risk factors and detect the most vulnerable people (Berengüí et al., 2016).

In the investigation of the origins of ED, a large number of psychological variables have traditionally been identified as risk factors for the onset and subsequent development of these pathologies. Probably the most analysed and confirmed by research have been body dissatisfaction, drive for thinness, low self-esteem and perfectionism (Castejón, 2017; Gismero, 2020). In addition, other variables such as self-esteem and self-concept problems, defective coping skills, and certain psychopathologies, such as anxiety, depression, and obsessive or compulsive disorders, have been shown to be related to ED to a greater or lesser extent (Castejón, 2017).

An important area of study within ED is the analysis of personality. Personality accounts for individual differences in characteristic patterns of thinking, feeling and behaviour (Kazdin, 2000), and includes a series of traits or dispositions, relatively stable over time, and consistent throughout situations, that explain each individual’s particular response style. Social contexts and stages of development are basic, involving change in order to adapt to interpersonal relationships and health issues.

Previous studies have found that personality plays a key role in the vulnerability, development, expression and recovery of different mental disorders (Levallius, 2018). Within this framework, it has been argued that personality is implicated in the occurrence, expression and maintenance of ED (Cassin & von Ranson, 2005). Different theoretical approaches suggest that personality traits could represent a predisposition or risk factors for ED, as well as modulating factors in the evolution of the disorder, side effects of the ED, different manifestations of the same underlying causal factor (Castejón, 2017; Krueger & Eaton, 2010).

Several personality characteristics have been linked to ED. Neuroticism has been proposed as a basic risk factor for the development of ED (Castejón & Berengüí, 2020; Gilmartin et al., 2022; Lilenfeld et al., 2006). Furthermore, in ED patients of different types, research has found high levels of these factors, as well as perfectionism, obsessive-compulsive traits, impulsivity, emotional dysregulation, negative emotionality, harm avoidance, sensation seeking, and low levels of self-directedness, cooperation and assertiveness, among others (Bénard et al., 2019; Bulik et al., 2006; Cassin & von Ranson, 2005; Claes et al., 2013; Farstad et al., 2016; García-Palacios et al., 2004; MacLaren & Best, 2009; Trompeter et al., 2022).

While there are different models that analyse personality, in recent years research which examines personality’s relationship with ED has taken up the Five-Factor Model (FFM) (Costa & McCrae, 1992), perhaps the model that has gathered the most empirical support so far, in view of the amount of research that has utilised it (Gilmartin, et al., 2022; Levallius, 2018). This model assumes that personality can be defined according to scores in five major dimensions or higher-order personality traits (neuroticism, extraversion, openness to experience, agreeableness and conscientiousness), which include interrelated sub-areas, and the states in which individual differences in personality are genetically based and stable (Costa & McCrae, 2008; McCrae & Costa, 1999). Using the instruments derived from this model, the NEO-PI-R questionnaire and its abbreviated version NEO-FFI (Costa & McCrae, 1992), data regarding the five main personality traits has been obtained both in clinical samples of ED patients and in populations at risk of developing the disorders. Based on this model, previous studies have confirmed the relationship of high neuroticism, and low extraversion and conscientiousness, with a higher incidence of ED, greater body dissatisfaction and disordered eating behaviours (Allen & Robson, 2020; Gilmartin et al, 2022).

Although substantial research data exists, the study of the relationship between personality and ED remains limited, and most research has exclusively examined the personality of patients with ED. Because of this limited research, and the need to delve deeper in the analysis of the factors that relate to vulnerability to ED, the present study aimed to analyse the relationships between personality and different risk variables for the development of ED in the in the population of female university students without disorders.

Method

The design used was non-experimental, cross-sectional and quantitative.

Participants

The study involved 627 adult women, Spanish university students, with an average age of 22.17 years (SD = 4.13), and an age range of between 18 and 38 years. By age, the highest frequency is 20 years of age with 150 participants (26.4%), followed by 21 years of age (n = 104; 18.3%) and 22 years of age (n = 66; 11.6%).

The criteria for study inclusion were to be of legal age and not to have been previously diagnosed with ED.

All the participants were registered students at public and private Spanish universities, studying degree programmes in Primary Education (21.24%), Early Years Education (19.57%), Nursing (12.09%), Sport Sciences (20.75%), Nutrition (15.14%) and Psychology (11.21%). The highest percentage were in their freshman year at university (34.25%), followed by those who were in their junior (25.63%) and senior (22.83%) years, and finally by students in their sophomore year (17.29%).

Instruments

Five-Factor Inventory (NEO-FFI). In order to obtain the data regarding personality traits the Spanish adaptation of the NEO-FFI was used (Costa & McCrae, 2008), a reduced version of the Revised NEO Personality Inventory (Costa & McCrae, 1992). The instrument is composed of 60 items and allows the rapid assessment of the five major personality factors: (1) Neuroticism (chronic predisposition to emotional distress versus emotional stability); (2) Extraversion (energetic and thrill-seeking versus sober and solitary); (3) Openness to Experience (curious and unconventional versus traditional and pragmatic); (4) Agreeableness (kind and trusting versus competitive and arrogant); and (5) Conscientiousness (disciplined and meticulous versus laidback and careless). The NEO-FFI, both in its original version and in its Spanish adaptation, presents adequate psychometric properties and a good internal consistency in all dimensions. In this study, there is good reliability (Cronbach’s alpha) for all factors: Neuroticism (a = .81), Extraversion (a = .83), Openness to Experience (a = .71), Agreeableness (a = .74), and Conscientiousness (a = .84).

Eating Disorder Inventory-3 (EDI-3). The EDI-3 inventory was used, developed by Garner (2004) and adapted to Spanish by Elosua et al. (2010). It is composed of 91 items, organised into 12 main scales, three specific scales related to eating disorders and nine general psychological scales not specific to eating disorders. The first three are called Eating Disorders risk scales, specifically: (1) Drive for thinness (extreme desire to be thinner, preoccupation with food and weight, and an intense fear of gaining weight) (a = .91); (2) Bulimia (predisposition to think about compulsive overeating and to compensate for binge eating by purging through vomiting) (a = .79); 3) Body dissatisfaction (dissatisfaction with the general shape of the body, and rejection of the size of specific areas of the body) (a = .85). The remaining nine scales evaluate psychological constructs that are conceptually relevant in the development and maintenance of eating disorders: Low self-esteem (a = .77), Personal alienation (a = .80), Interpersonal insecurity (a = .69), Interpersonal alienation (a = .85), Interoceptive deficits (a = 0.78), Emotional dysregulation (a = .75), Perfectionism (a = .73), Asceticism (a = .79), and Maturity fears (a = .71).

Socio-demographic form. An ad hoc questionnaire was administered in order to collect data such as age, degree programme and year of study, as well as the institution at which the students were registered.

Procedure

Once the aims of the study were set and selected as well as the type of population on which the research was to be carried out, the pertinent permission was requested from the universities. After receiving authorisation to conduct the study, the teachers responsible for the groups that were to participate were contacted and sent a detailed report regarding the aims and duration of the study and what the work would consist of The questionnaires were administered collectively, anonymously and voluntarily during class time. The students were informed that a study was going to be carried out regarding ED and Personality and they were also advised of the confidential treatment that the data provided would receive. Once their collaboration was requested and obtained and they provided signed consent, the battery of questionnaires was administered.

Those responsible for the research were present during the administration of the questionnaires in order to provide help if necessary and to verify the correct and independent completion of the questionnaire by each subject.

Statistical analysis

Data analysis was performed using the programme IBM SPSS Statistics v.27 (IBM, Armonk, NY, USA). We calculated Pearson’s correlation coefficients to observe patterns of common variation among the variables. We conducted regression analysis, specifically the method of successive steps (Stepwise), to determine the contribution of the independent variables (personality traits) in the explanation of the dependent variables (specific scales of eating disorders and general psychological scales). In each analysis, the five personality factors were introduced. We set the level of statistical significance for these statistics at p < .05.

Results

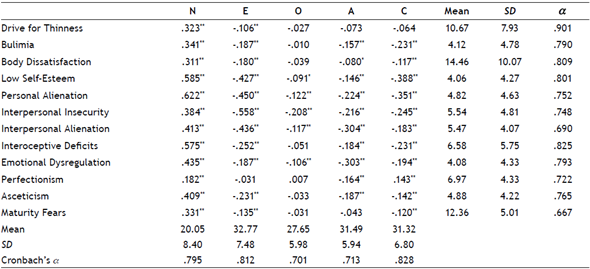

Table 1 presents the analysis of correlations between the personality factors and the risk scales, means, standard deviation and reliability of the scales. The positive correlation of neuroticism with all the scales was found, as well as the negative sign in the relationships of the remaining personality factors with the risk and psychological scales.

Table 1 Bivariate correlations between risk scales, psychological scales and personality

Note: * p < .05; ** p < .01; N: Neuroticism; E: Extraversion; O: Openness to experience; A: Agreeableness; C: Conscientiousness; a: Cronbach’s alpha.

Significant correlations were found between almost all scales and Neuroticism. It emphasises the correlations with the risk scales Drive for thinness (r = 0.323, p < 0.01), Bulimia (r = 0.341, p < 0.01), and Body dissatisfaction (r = 0.311, p < 0.01). It also emphasises the magnitude of the association between Neuroticism and the scales of Low self-esteem (r = 0.585), Personal alienation (r = 0.622), Interpersonal insecurity (r = 0.384), Interpersonal alienation (r = 0.413), Interoceptive deficits (r = 0.575), Emotional dysregulation (r = 0.435) and Asceticism (r = 0.409). Correlations between all of the psychological scales and Extraversion were of negative sign, and the principal ones were with Low self-esteem (r = -0.427), Personal alienation (r = -0.450), Interpersonal insecurity (r = -0.558), and Interpersonal alienation (r = -0.436). Most scales were negatively associated with Agreeableness, and the main correlations were with Interpersonal alienation (r = -0.304) and Emotional dysregulation (r = -0.303). Conscientiousness was negatively associated to all scales, with small magnitude, with the exception of Low self-esteem (r = -.388) and Personal alienation (r = -0.351). The correlations between Openness to experience and the scales were of small magnitude.

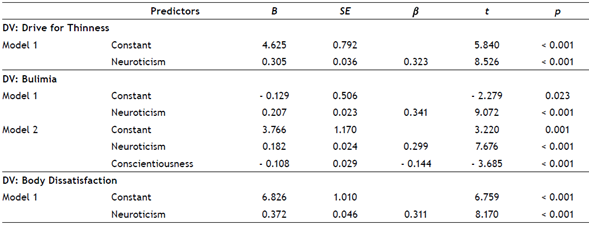

According to results of regression analysis (Table 2), Neuroticism accounts for 11% of variance in predicting Drive for thinness (R2 = 0.11, adjusted R2 = 0.11; F(1, 625) = 72.687, p < 0.001). Regarding Bulimia, Neuroticism accounts for 12% of variance (R2 = 0.12, adjusted R2 =,12; F(1, 625) = 82.302, p < 0.001), and Conscientiousness (b = -0.144) figured accounting for an additional 2% of variance (R2 = 0.14, adjusted R2= 0.14; F(2, 624) = 48.771, p < 0.001). Also, Neuroticism accounts for 10% of variance in predicting Body dissatisfaction (R2 = 0.10, adjusted R2 = 0.10, F(1, 625) = 66.750, p < 0.001).

Table 2 Regression analysis for predicting the risk scales based on personality traits

Note. DV= Dependent Variable

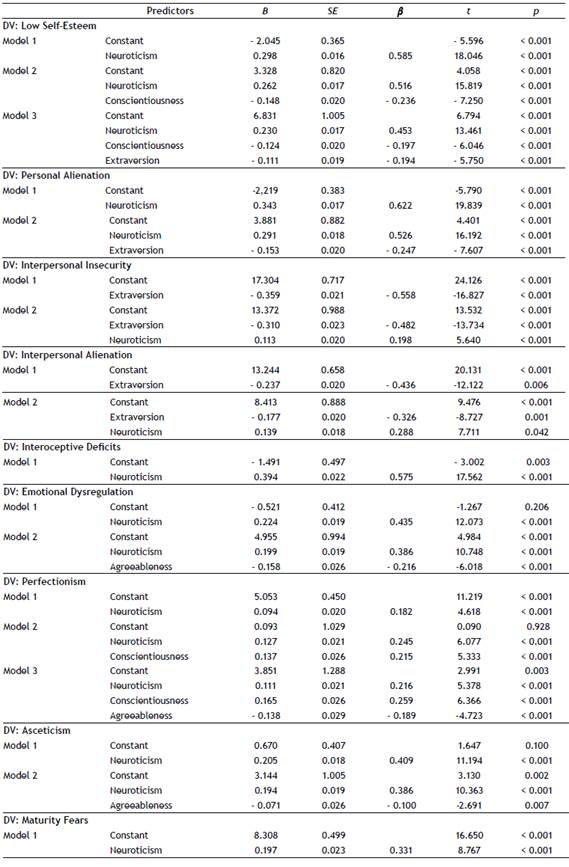

The relevant psychological scales in the development and maintenance of ED were analysed (Table 3). The standardised beta coefficients indicated the relative influence of the variables in the models.

Table 3 Regression analysis for predicting the psychological scales based on personality traits

Note. DV: Dependent Variable

Neuroticism was the predictor of the great majority of scales. It predicted 34% of Low self-esteem variance (R2 = 0.34, adjusted R2 =0.34, F(1, 625) = 325.668, p < 0.001), and together with Conscientiousness and Extraversion explained 42% of the variance of Low self-esteem (R2 = 0.43, adjusted R2 = 0.42, F(3, 623) = 152.991, p < 0.001).

Neuroticism was the only predictor variable of Interoceptive deficits (R2 = 0.33, adjusted R 2= 0.32, F(1, 625) = 308.434, p < 0.001), and Maturity fears (R2 = 0.11, adjusted R2 = 0.10, F(1, 625) = 76.855, p < 0.001). Furthermore, Neuroticism predicted 38% of Personal alienation variance (R2 = 0.38, adjusted R2 = 0.38, F(1, 625) = 393.603, p < 0.001), and together with Extraversion predicted 44% of variance (R2 = 0.44, adjusted R2 =0.44, F(2, 624) = 243.645, p < 0.001). Neuroticism was the main predictor of Emotional dysregulation (R2 = 0.19, adjusted R2 = 0.18, F(1, 625) = 145.767, p < 0.001), and combined with Agreeableness (ΔR2 = 0.04) accounted for 23% of the variance (R2 = 0.23, adjusted R2 = 0.23, F(2, 624) = 95.096, p < 0.001). Neuroticism was also the main predictor of Perfectionism (R2= 0.03, adjusted R2 = 0.03, F(1, 625) = 21.327, p < 0.001). In the last model, Neuroticism, Conscientiousness and Agreeableness explained 11% of the variance of Perfectionism (R2 = 0.11, adjusted R2 = 0.11, F(3, 623) = 24.913, p < 0.001). Regarding Asceticism, Neuroticism was the main predictor (R2 = 0.16, adjusted R2 = 0.16, F(1, 625) = 125.311, p < 0.001). Neuroticism and Agreeableness explained 18% of the variance of Perfectionism (R2= 0.18, adjusted R2 = 0.18, F(2, 624) = 66.903, p < 0.001).

The factor Extraversion predicted 31% of Interpersonal insecurity (R2 = 0.31, adjusted R2 = 0.31, F(1, 625) = 283.163, p < 0.001), and 35% of variance together with Neuroticism (R2 = 0.36, adjusted R2 = 0.35, F(2, 624) = 164.467, p < 0.001). Extraversion was the main predictor of Interpersonal alienation (R2 = 0.19, adjusted R2 = 0.18, F(1, 625) = 146.945, p < 0.001). The model integrating Extraversion and Neuroticism explained 25% of the variance in Interpersonal alienation (R2 = 0.26, adjusted R2 = 0.25, F(2, 624) = 110.074, p < 0.001).

Discussion

In the search for new data that would contribute to furthering knowledge in this field, the present study analysed the relationships between personality and different risk variables for the development of ED.

Among all the results, the large effect of the neuroticism factor stands out, as its significant associations with an increased ED risk were confirmed. Significant correlations of neuroticism were found with all the scales assessed, especially with the EDI-3 risk scales (drive for thinness, bulimia and body dissatisfaction), and was the main predictor variable of the variance of the three risk scales and several psychological variables related to ED.

The importance of neuroticism is basic as it is negatively associated with important life outcomes such as professional success, relationship satisfaction, subjective well-being, physical health, mental health and longevity (Levallius et al., 2020), and it is consistently present in most psychopathologies, including eating disorders (Claridge & Davis, 2001). The results found are in line with most studies that have previously analysed personality and eating disorders, pointing to neuroticism as a clear predisposing factor for eating disorders (Brown et al., 2020; Bulik et al., 2006; Lilenfeld et al., 2006). Neuroticism plays a decisive role in the initiation, expression and maintenance of eating disorders (Cassin & von Ranson, 2005), and furthermore, greater neuroticism is found to be associated with the severity of eating disorder symptoms in clinical and non-clinical populations (Fischer et al., 2017).

Although analysis has mainly focused on clinical groups (Atiye et al., 2015), studies with non-clinical populations show high correlations of neuroticism with bulimia and preoccupation with food (MacLaren & Best, 2009), bulimia and drive for thinness (Castejón, 2017; Miller et al., 2006), body dissatisfaction (Castejón, 2017), personal alienation (Galarsi et al., 2009), and increased disordered eating behaviour (Gilmartin et al., 2022). It has also been confirmed as the main predictor of the variance of eating disorders risk (Castejón, 2017), and is associated with a higher number of eating disorder behaviours (Calland et al., 2020; Castejón, 2017).

Based on the Five-Factor Model (FFM), neuroticism is defined as a trait closely related to negative affectivity, and is distinguished by facets such as anxiety, hostility, depression, self-consciousness, impulsivity, or vulnerability to stress (Costa & McCrae, 1992, 2008). In addition, the results have found an association between neuroticism and the risk scales, as well as fundamental variables such as interoceptive deficits and emotional dysregulation, which in the EDI-3 make up the index of affective problems, which assesses the ability to correctly identify, understand and respond to different emotional states, and is associated with characteristics such as mood instability or emotional lability, among others (Garner, 2004; Elosua et al., 2010). Based on these characteristics that most neurotic people have, we can assume that they present a higher eating disorder risk due to their emotional problems, and that they enhance their obsession with thinness, their constant preoccupation with their weight or body shape, or with food and its quantity (Castejón & Berengüí, 2020), and finally also increase defective emotional regulation.

With regard to extraversion, the factor recorded negative correlations with all scales, but the relationships with the risk scales are of small magnitude. In addition, negative correlations of moderate magnitude were obtained with the scales of low self-esteem, personal alienation, interpersonal insecurity and interpersonal alienation, and it is the main predictor variable of the variance of the latter two.

Trait extraversion has shown less research evidence than neuroticism, with no strong associations of extraversion with eating disorders in the general population or university students (Finlayson et al., 2002). Nonetheless, the results of this study were similar to those obtained in previous studies, in which university students recorded an inverse relationship between extraversion and drive for thinness in women (Cortez, 2015; Galarsi et al., 2009), and an inverse association between extraversion, bulimic symptomatology and body dissatisfaction (Cortez, 2015). Likewise, male and female university students with low levels of eating disorder risk also had significantly higher extraversion scores than subjects in medium- or high-risk groups (Castejón, 2017). In addition, lower extraversion has been linked to greater eating disturbance in women with high neuroticism (Miller et al., 2006). In patients with bulimic eating disorders, binge eating cessation was positively predicted by extraversion (Levallius et al., 2020).

Extraversion implies a tendency to be sociable, optimistic, to enjoy social contact, and individuals with high scores in this factor are lively, energetic, and report more positive emotions in everyday life than those who are more introverted (McCrae & Costa, 1999). Based on our results, we can suggest that the characteristics of cordiality, gregariousness, assertiveness, energy, emotion-seeking and predominance of positive emotions, which usually define extraverted people, can be considered as positive in this case. This is because they are inversely related to low self-esteem, and aspects such as the feeling of emotional emptiness, loneliness, difficulty in expressing one’s own thoughts and feelings to other people, or the feeling of lack of affection and understanding from others, which characterize the psychological scales that in this study are related to extraversion (Castejón, 2017).

The correlations of the conscientiousness trait were also, as with extraversion, of negative sign and moderate magnitude with low self-esteem and personal alienation; although with the risk scales the relationships are small, and non-existent with drive for thinness. It is a predictor together with neuroticism of bulimia in negative sense, and the main predictor of perfectionism together with neuroticism and agreeableness.

Previous evidence regarding the relationship of the conscientiousness factor to eating disorders has shown interesting data. It has been argued that liability is one of the traits that perpetuate the clinical state (Katzman, 2005). In non-clinical populations, low scores on conscientiousness and agreeableness, and high scores on neuroticism and openness to experience, confirmed an increased eating disorders risk (Ghaderi & Scott, 2000). In university students, those at low risk of ED had much higher conscientiousness scores than students in medium- or high-risk groups (Castejón, 2017). Also, differences in conscientiousness have been found in adolescents with eating disorders compared to a non- confirmed increased eating disorders risk (Dufresne et al., 2020).

Conscientiousness refers to an individual’s tendency towards organisation and achievement, and the subject is responsible, conscientious, hard-working, competent and organised, as opposed to people who are low in responsibility and tend towards low self-discipline (Costa & McCrae, 2008; McCrae & Costa, 1999). We consider that the results suggest that higher scores in this trait are associated with more confident, decisive and scrupulous individuals, which may lead to better emotional management that manifests itself in higher self-esteem, and that this greater control prevents impulsivity from leading to harmful behaviours such as binge eating or vomiting (Castejón, 2017).

The agreeableness factor registered negative correlations with all the EDI-3 scales, the main ones being with interpersonal alienation and emotional dysregulation, and it was also a predictor of emotional dysregulation, perfectionism and asceticism, together with neuroticism. There is little previous data confirming the association of Agreeableness with eating disorder risk. Existing evidence on this trait indicates that patients with eating disorders score lower than controls on agreeableness (García-Palacios et al., 2004). As previously mentioned, low scores in agreeableness and conscientiousness, and high scores in neuroticism and openness to experience, increase the confirmation of an increased eating disorders risk (Ghaderi & Scott, 2000).

The agreeableness factor characterises people who are altruistic, helpful, trusting, frank and sincere, and show sensitivity and concern for others (Costa & McCrae, 1999). The results of this study seem to indicate positive data regarding this factor, as women with higher agreeableness scores tend to have lower disappointment, distance, estrangement, and lack of trust in relationships, which characterises the interpersonal alienation scale, and also a high agreeableness leads to less emotional dysregulation, and therefore less emotional instability, impulsivity and irascibility (Elosua et al., 2010). Therefore, in this case we can consider agreeableness as a beneficial factor against ED, as it was related to aspects such as better impulse regulation and better moods, as well as less difficulty in expressing thoughts and feelings to others. All of these are characteristics that have been identified as being associated with eating disorders and a better or worse prognosis (Garner, 2004).

Regarding openness to experience, no remarkable results were found in this study, although previous studies confirmed that higher scores in openness are associated with a higher number of eating disorder behaviours (Calland et al., 2020), and that in patients with bulimic eating disorders, remission and overall symptom reduction was positively predicted by the factor (Levallius et al., 2020).

Limitations and strengths

Regarding the limitations of the study, we should note the design nature, since being a cross-sectional study it is only possible to check the levels of the variables analysed at a specific moment in time. It is not possible to check their possible evolution over time. We must also consider the external transferability/validity of the results with respect to other contexts, as the present study analysed only female university students.

For these reasons the present study may provide opportunities for future research that will consider these limitations and that will contribute to expanding the literature in this field. It would be important to study the relationships between personality and ED risk in women of other age groups, as well as to analyse men, in order to be able to test whether different personality traits have the same associations in both genders. Women and men from other areas of society, not just students, should also be studied. Future longitudinal research is also needed to identify risk factors for the development of FEDs.

Results such as those of stemming from this study contribute to help identify at-risk populations and adopt prevention-oriented solutions (Dufresne et al., 2020). Knowledge of personality traits is essential. Personality studies can contribute to clinical practice, as models such as the FFM provide many benefits such as, obtaining a parsimonious and easily understandable profile of people, providing clinically relevant information on both adaptive and maladaptive traits, and the possibility of designing an individualised treatment plan, taking into account strengths and problematic traits, amongst other characteristics (Levallius, 2018; Widiger & Presnall, 2013).

Conclusion

The study supported the importance of personality in the risk of developing ED. The close association between neuroticism and risk variables is confirmed, and its relationship with psychological constructs such as low self-esteem, emotional dysregulation or perfectionism, that are conceptually relevant in the development and maintenance of FED. In addition, extraversion, conscientiousness and agreeableness demonstrated their negative relationship with the different scales. The study of personality should help to identify at-risk populations, enable the adoption of solutions aimed at the prevention of ED.