Most research on the effects of induced abortion on women’s mental health has been conducted in high-income countries (APA, 2008; Biggs et al., 2017; National Collaborating Centre for Mental Health, 2011; van Ditzhuijzen, 2019). However, rigorous evidence shows that abortion is not causally associated with adverse mental health outcomes (Biggs et al., 2018; Lewis & Dave, 2021; Major et al., 2009; Steinberg et al., 2014; Stotland, 2019; van Ditzhuijzen et al., 2017).

Depression has been one of the most researched outcomes subsequent to an abortion. Notwithstanding, the evidence has revealed that several factors could be confounding this association (Boersma et al., 2014; Charles et al., 2008; Faure & Loxton, 2003; Foster et al., 2015; Pedersen, 2008; Rees & Sabia, 2007). For example, a history of gender-based violence (Major et al., 2009; Roberts et al., 2014; Steinberg et al., 2016; Oram et al., 2017; Zia et al., 2021), the previous presence of a mental health problem (Steinberg & Rubin, 2014; van Ditzhuijzen et al., 2017), or the perceived stigma of abortion (Major et al., 2009; López et al., 2019; Ramos-Lira et al., 2021; Sorhaindo et al., 2014; Steinberg et al., 2016; Zia et al., 2021).

In light of this background, we hypothesise that women who abort may have mental health conditions that are not the result of an abortion procedure and that other prior or concomitant factors may lead to these mental health outcomes. Likewise, it is relevant to carry out studies on the subject in Latin America, taking into account that although this region has highly restrictive abortion laws, it also has the highest rates of induced abortion worldwide (Galli, 2020; Singh et al., 2018). Consequently, there are many barriers to monitoring and researching this issue (Biggs et al., 2020; Boersma et al., 2014; Cedeño & Tena Guerrero, 2022; Maroto-Vargas, 2010).

In 2021, the Mexican Supreme Court of Justice declared it unconstitutional to criminalize abortion in an absolute way. Legal termination of pregnancy by public services exists in ten states and is available up to the 12th week of gestation. Moreover, services have existed in Mexico City since 2007, when abortion was decriminalised, and are currently the most consolidated in the country.

This paper aims to determine the prevalence of probable major depressive episode (PMDE) in women who legally terminated a pregnancy by way of public service in Mexico City. It also seeks to identify whether there are any associated psychosocial and contextual factors.

Method

Type of study and participants

The research was cross-sectional and ex-post-facto, involving 274 Mexican women who returned for a follow-up medical examination two weeks after a medical abortion provided by a public service of Legal Termination of Pregnancy (LTP) in Mexico City. Eligibility for the study included being 15 years of age or older and agreeing to participate in an interview. Exclusion criteria included women a) that had performed the procedure with manual vacuum aspiration (MVA), b) that had a severe intellectual or motor disability that would not allow them to answer the questionnaire, or c) that had attended the service for some other legal reason.

Measures

A structured interview included questions regarding age, education, occupation, socioeconomic status, number of previous pregnancies, previous abortions, number of children, and the presence of a partner.

Depression was measured using the Revised Version of the Depression Scale of the Center for Epidemiological Studies (CES-D-R;González-Forteza et al., 2008). The instrument includes 35 questions with five closed answer options referring to the number of days in which symptoms persisted (0, 1-2, 3-4, 5-7, 8-14), with regard to the last 14 days. It was created in 1977 (Radloff, 1977) and revised in 2004 (Eaton et al., 2004) for measuring the symptoms defined by the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th Edition (DSM-IV;APA, 1994) of a major depressive episode. In the present study, the instrument obtained an α = 0.95. Women were classified using an algorithm for a probable major depressive episode (PMDE) that evaluates the presence or absence of symptoms in each of the nine criteria for a major depressive episode. Hence, a score threshold is not used for depression screening in our study.

To assess whether participants had experienced previous depression, they were asked the following question after completing the CES-D-R scale: “In the last 12 months or from (the current month but referring to the last year) and until you attended the LTP service, have you had symptoms like the ones I just mentioned at the same time and with such intensity and duration that you would say you were depressed?” Againanswer options were dichotomous: yes or no.

Child Sexual Abuse was assessed with one question: “Before the age of 15, has someone, whether a family member or anyone else, ever stroked, touched, or caressed some part of your body; or did they make you touch any part of their body, or did they have sex with you when you were very young or against your will?” Answer options were, again, dichotomous: yes or no. Another question included was regarding forced sex: “Starting at age 15, did anyone force you to have sex or when you did not want to?” Once again, the answer options were a simple yes or no (Ramos-Lira et al., 2001).

Intimate Partner Violence (IPV) during the last year prior to going to the LTP service was evaluated with four items, taking as a reference the current or the latest partner (Lira & Méndez, 2008). Two items assessed psychological abuse (You were yelled at or insulted; threatened to be physically harmed, for example, to be hurt or even killed), a second item considered physical abuse (You were physically abused; this includes being slapped, kicked or hit). Another one referred to sexual abuse (He has had sex with you by force, even though you didn’t want to), and finally, there was an economic violence item (He has complained about how you spend money). As mentioned above, the response options were all dichotomous. For the analyses, a single IPV variable was created considering the presence of at least one of the four items (α = 0.72); all answers were dichotomous.

The Individual Abortion Stigma Scale (ILAS; Cockrill et al., 2013) comprises 20 items and measures four dimensions: Worries about judgment, Isolation, Self-judgment, and Community condemnation. These items have four Likert-type response options for the first two dimensions (from 1 = nothing to 4 = a lot, subscale range 1-4), while the third and fourth have five options (from 1 = strongly disagree, to 5 = strongly disagree; and from 1 = none, to 5 = most people, respectively, subscale range 1-5). Subscale scores were obtained by adding each item and dividing the sum by the number of questions. The range for the total score was 1-4.35. There was no set cut-off point. The scale showed good reliability (α = 0.88 to 0.98).

At the end of the interview, if a participant had presented a history of depression, current symptoms, a severe case of violence within the last 12 months, or if she had requested care, she was offered a referral to the hospital’s psychiatry or psychology service or to another institution.

Procedure

Interviews with users of the LTP service took place between November 2018 and November 2019. Five interviewers participated in data collection; all were psychologists and had previously participated in specialised training.

A researcher and the social worker assigned to the corresponding public service invited all women attending follow-up consultations to participate. Participants signed an informed consent letter and were invited to a quiet, private location to be interviewed directly. The questionnaire was then applied during the waiting time for the follow-up ultrasound.

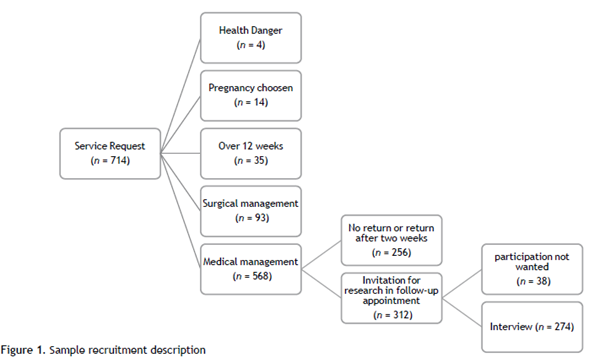

During the selected time for data collection, 714 women attended the service. Of these, four requested an interruption for reasons associated with a danger to their health; 14 voluntarily withdrew from the service and did not complete the process; the gestation time of 35 women was more than 12 weeks advanced at the time of ultrasound, and they could not receive the termination, and 93 others performed the procedure with MVA. Of the 568 who performed the procedure with medication, 460 were eligible with regard to the time when the research team showed up at the service to conduct the interviews. Of those eligible, only 312 returned for the discharge appointment and they were invited to participate; of these, 274 accepted the interview (87.8%) (Figure 1).

Ethical considerations

This research project was evaluated and approved by the Ethics Committee of the Instituto Nacional de Psiquiatría Ramón de la Fuente Muñiz, reference CEI/C/001/2015, and by the Research and Bioethics Subcommittee of the Secretaría de Salud of Mexico City (SSDF/ DGPCS/DEI/SECI/ JUDI /1279/18).

Statistical analyses

Analyses were performed in STATA 14.0. The descriptive data of the variables were analysed in absolute frequencies. Bivariate analyses were performed between psychosocial variables and PMDE using Student’s x2 or T-tests with a p < .05. Odds ratios (ORs) and confidence intervals (95% CI) were estimated using a logistic regression model, including variables significant in the bivariate analysis and adjusted for age, education, occupation, socioeconomic status, and PMDE as the outcome.

Results

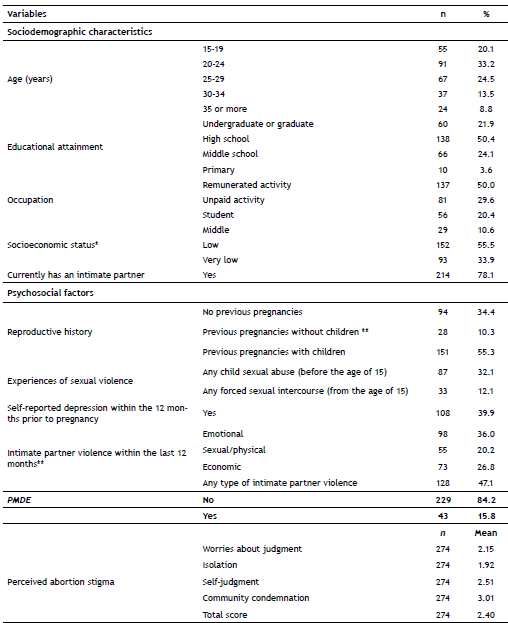

Most women were between 20 and 29 years old (57.7%). Half had completed secondary school (50.4%), and approximately the same proportion reported having a paid activity. Most participants had a very low or low socioeconomic status (89.4%). Almost four out of five mentioned having a partner (78.1%); half reported cohabiting with him.

65.6% had been pregnant before, and 10.3% had undergone a previous induced or spontaneous abortion. In addition, 32.1% reported child sexual abuse (before age 15), and 12.1% were forced to have sex after that age. Two out of five (39.9%) reported depression in the year prior to the abortion; 47.1% had experienced IPV in the past 12 months, with emotional violence being the most common form. 15.8% of the sample presented a PMDE. Perceived abortion stigma was not very high, as observed in the scale’s total score, with worries concerning judgment and community condemnation being the highest dimensions (Table 1).

Table 1 Descriptive statistics of the study sample (n = 274)

* Evaluated by a social worker with the classification of the LTP service, **Add up to more than one hundred per cent because categories are not mutually exclusive.

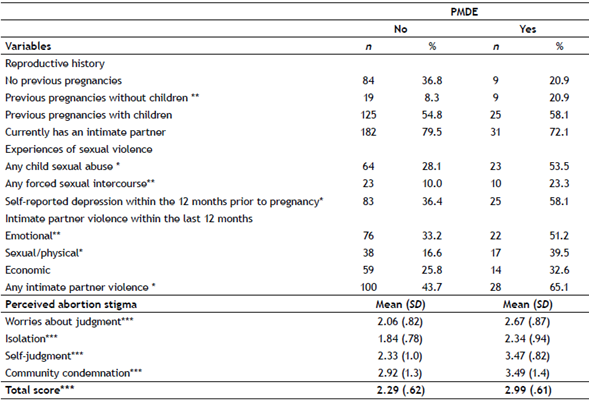

Regarding reproductive history, Table 2 shows that women with PMDE were more likely to have been pregnant before without having had children (due to induced abortion/ miscarriage) than those without PMDE (20.9% vs. 8.3%). Also, those with PMDE were more likely to report child sexual abuse compared to those without PMDE (53.5% vs. 28.1%) (χ2 (1) = 10.72, p = 0.001). Women with PMDE were also more likely to have experienced forced sex after age 15 (23.3% vs. 10%) (χ2 (1) = 5.93 p = 0.015) as well as IPV within the past 12 months (65.1% vs. 43.7%) (χ2 (1) = 6.68, p = 0.010). Moreover, those with PMDE were more likely to report depression during the 12 months before pregnancy (58.1% vs. 36.4%) (χ2 (1) = 7.13, p = 0.008).

Table 2 Bivariate analysis of psychosocial variables and PMDE (n = 274)

*χ2 p < = 0.01, **χ2 p < = 0.05, *** Student’s T p < = 0.01

Women with PMDE reported higher averages of abortion stigma in the Total Score compared to those without PMDE (2.99 vs. 2.29), (t (270) = 6.86, p <. 001), and likewise in all four dimensions compared to those without PMDE: Worries about judgment (2.67 vs. 2.06), (t (270) = 4.48, p <,001); Isolation (2.34 vs. 1.84), (t (270) = 3.71, p <,001); Self-judgment (3.47 vs. 2.33), (t (270) = 6.96, p <,001); and Community condemnation (3.49 vs. 2.92), (t (270) = 2.58, p = 0.010).

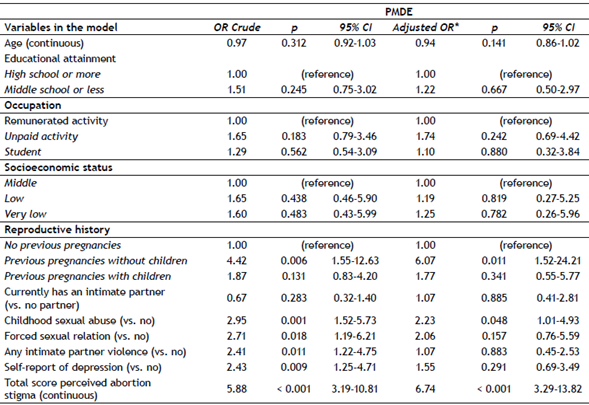

As shown on Table 3, unadjusted estimates of reproductive history, child sexual abuse, forced sex after the age of 15, any IPV, self-report of depression, and abortion stigma were associated with PMDE. Subsequently, in the final logistic regression model and adjusting for sociodemographic characteristics, higher ORs were found among women who had been pregnant but had not borne children (OR = 6.07; 95% CI = 1.52-24.21); likewise for those who reported child sexual abuse (OR = 2.23; CI 95% = 1.01-4.93) and for those with higher levels of perceived abortion stigma (OR = 6.74; 95% CI = 3.29-13.82).

Discussion

The findings contribute to understanding the abortion situation in Latin America, where there are practically no studies on the subject due to the legal restrictions associated with its practice. The prevalence of PDME was 15.8%, similar to or lower than that reported in meta-analyses of studies of women who continued a pregnancy, which ranges from 15.0% to 20.7% (Dadi et al., 2020; Yin et al., 2021).

Abortion-related stigma was the most crucial factor in the PMDE model. This result is consistent with results reported in other international studies (Biggs et al., 2020; O’Donnell et al., 2018; Steinberg et al., 2016) and with the proposals of authors such as Rostagnol (2014), who points out that while the decriminalisation of abortion solves the problem of unsafe abortions, it does not generate automatic changes in moral beliefs.

Although attitudes toward abortion tend to be more favourable after legalisation, and the circumstances for performing it are more likely to be considered reasonable if the law allows it (Sorhaindo et al., 2014), abortion stigma has lasting effects on people’s lives (Assis & Erdman, 2021). This stigma is a central component of anti-choice narratives, in which abortion is constructed as a shameful, immoral, and deviant practice (Amuchástegui et al., 2015; Cullen & Korolczuk, 2019; Zia et al., 2021).

Abortion stigma can produce feelings of guilt and shame that often lead women to keep the experience secret. (Cedeño & Tena Guerrero, 2022; Hanschmidt et al., 2016; O’Donnell et al., 2018; Shellenberg et al., 2011; Sorhaindo et al., 2014; Zia et al., 2021). It also often causes fear of being judged by relatives and significant others, which can ultimately lead to psychological distress (Biggs et al., 2020; Hanschmidt et al., 2016) or even symptoms of depression (Steinberg et al., 2016). This concern about being judged also interferes with the search for abortion services (Hernández-Rosete & Estrada-Hipólito, 2019; Turan & Budhwani, 2021).

Having a history of abortions and the absence of children was a risk factor for depression that may be related to idealised beliefs about motherhood and stigmatised precepts about abortion. Women who have decided to terminate several pregnancies and do not have children may feel selfish or immoral because they perceive that they are challenging family expectations and cultural norms regarding motherhood and womanhood (Kumar et al., 2009; Orihuela-Cortés et al., 2022; Russo, 1976). Stigmatisation provokes a narrative in which women consider it valid to have a single abortion for a justified reason (Amuchástegui et al., 2015). Women with more than one induced abortion are regarded as careless or promiscuous.

In addition to all of the above, this study evidences the relevance of child sexual abuse. The literature regarding this issue shows that this is a common risk factor for the development of mental health disorders in general (Hailes et al., 2019) and depression in particular (Li et al., 2020), as well as for subsequent sexual victimisation, unwanted pregnancy (Sumner et al., 2015), reduction of contraceptive use (Grose et al., 2021), and repetition of induced abortion (Fisher et al., 2005).

Limitations and suggestions

Despite the strengths of this study, it is important to note its limitations:

The design was cross-sectional, so the causal nature of the relationships examined cannot be determined. A prospective study could provide better information to discriminate the magnitude of the different factors considered in the presence of PMDE.

Only one service participated in the study, which does not necessarily mean that this population is representative of other LTP clinics.

Interviews were conducted exclusively with women who returned to their discharge appointment following a medical abortion because this is the most frequent procedure afforded by LTP services in Mexico City (78.95% vs. 21.04% for MVA). Unfortunately, we do not know how patients who returned for their follow-up appointments differ from those who did not return.

The report of a low and very low socioeconomic level (89%), considering the high educational level of the participants, is striking. In this sense, it is crucial to consider a possible bias in this variable given that the social worker of the service assigned the participants’ socioeconomic level based on an institutional criterion that allows for the interruption of pregnancy to be free.

It is urgent to promote a “social” decriminalisation of abortion, that is, to accept that induced abortion is a frequent procedure and, most importantly, a right for women who wish to terminate a pregnancy for whatever reason. Moreover, making women feel less stigmatised, decreasing misinformation related to the termination of a pregnancy, improving their perception of self-efficacy and self-care as well as detecting experiences of violence could reduce the emotional burden related to making decisions concerning their sexual and reproductive health.

These findings coincide with the arguments on reproductive autonomy put forth by the Mexican Supreme Court of Justice in 2021. Obstacles in women’s sexual and reproductive trajectory for making free decisions disrupt their care structures, where preventing an unintended pregnancy becomes very unlikely or controllable for them. Therefore, abortion can be seen as a therapeutic intervention that guarantees their right to health and the free development of their personality.

Services must be available, accessible, and of high technical quality. They should include post-abortion counseling and clinical considerations with regard to the impact of stigma and violence on women’s mental health and choices. Establishing intra-hospital pathways between different services that guarantee integral health when someone requires this type of care is crucial. Sensitive personnel with active listening skills are also required to establish a doctor-patient relationship focused on the needs of the women in each case. Finally, it is particularly relevant to analyse whether a brief clinical intervention to explore stigmatising ideas could help to anticipate depressive symptoms following the termination of a pregnancy1 2.