Introduction

Since the pioneering work of Enright et al. (1989), social psychologists have examined the determinants of forgiveness in people (Enright & Fitzgibbons, 2000; McCullough et al., 2000; Worthington, 2005; Worthington & Wade, 2020). According to Fehr et al. (2010), the most important determinants are situational. In other words, the willingness to forgive is strongly conditioned by the concrete circumstances surrounding the transgression. These circumstances are typically (a) the perceived initial severity of the consequences of the transgression or the degree to which the consequences are mitigated, (b) the perceived intentionality of the transgression or the degree of carelessness attributable to the transgressor, (c) the transgressor’s subsequent behaviour (e.g., whether he or she offers to repair the damage), and (d) the attitudes of peers, who may or may not encourage forgiveness. A great quantity of work has shown that the more severe the consequences are perceived to be, the more intent is perceived to be present, and the less the transgressor recognises the seriousness of the act, the less willing people are to forgive (Gauché & Mullet, 2008; Vera Cruz & Mullet, 2019). In relation to the types of damage, studies previously conducted in Colombia (López López et al., 2013 and 2018; Pineda-Marín et al., 2018 and 2019) highlight that people give relevance to more than the type of harm, it is the intention of the aggressor and whether he/ she asks for forgiveness for what occurred.

While it is undeniable and logical that the willingness to forgive in concrete situations is strongly determined by the circumstances, it is also partly determined by the victim’s personality. Depending on whether the victim is an agreeable person or not, emotionally stable or not, empathetic or not, the willingness to forgive in each concrete case will be different (Hodge et al., 2020; Mullet et al., 2005). It is also remarkable that some people declare themselves unable to forgive under any circumstances, while others declare themselves willing to forgive under any circumstances (Girard & Mullet, 1997; Pineda Marin et al., 2018). In these two extreme cases, these people express principled positions that reflect strong dispositions towards forgiveness, which in and of themselves completely determine the willingness to forgive.

Finally, some studies have shown that the impact of concrete circumstances on the willingness to forgive may depend on the victim’s personality (situational x dispositional interaction; Díez-Deustua, 2015). Gauché and Mullet (2008), for example, have shown that the emotional stability personality factor moderates the impact of the cancellation of consequences on the willingness to forgive.

Until recently, most studies on the determinants of forgiveness have been conducted in Western countries. Nevertheless, authors from other parts of the world have made contributions. For example, Rique et al. (2020) recently synthesised the contributions of Latin American authors. They have shown that most of the instruments used to measure forgiveness in Western countries can be easily adapted to Latin American populations, reflecting the fact that forgiveness is conceived and practiced in a rather similar way in Latin America and that therefore the findings of studies conducted in Western countries can, mutatis mutandis, be applied to the Latin American sphere (see also Bagnulo et al., 2009).

With specific reference to Colombia, the country in which the present study was conducted, Pineda-Marín et al. (2018) examined the reactions of people living in and around Bogotá to an everyday situation in which a patient had been the victim of a medical error and had suffered considerably as a result. For 55% of the participants - more frequently people of middle or higher social classes - the willingness to forgive depended mainly on two circumstances: the degree to which the consequences of the medical error had subsided and the subsequent behaviour of the doctor responsible for the error. When the consequences had virtually disap peared and the doctor had come to the patient’s bedside in person to apologise and express regret, then the willingness to forgive was high. Initial severity played only a minor role. For 24% of the participants - more frequently people from lower social classes - the willingness to forgive was always very high. It depended only marginally on the concrete circumstances. For 15% of the participants - more frequently atheists or people with little education - the willingness to forgive was, on the other hand, always minimal.

Although there is evidence of the existence of several studies on forgiveness, particularly in the Colombian context, there are no quantitative studies on this topic with indigenous populations. Accessing this population in Colombia poses several challenges, primarily due to the fact that they live in remote and inaccessible territories, not all of them speak Spanish, and entering their territories requires permission from their authorities. According to the report of the Truth Commission (2022), indigenous peoples in Colombia have been subject to violence with colonial legacies and structural racism, including forced disappearances, assassinations of authorities and community members, violation of their territory, sacred places and cultural identity, violence against women, torture, massacres, and others. Understanding their views on forgiveness in various situations related to these violations will help us better understand this topic and consider their worldview for strengthening peace processes with this population.

The Present Study

The current study aimed to investigate the willingness to forgive among people from various ethnic minorities in Colombia, with a particular focus on the Wayuu community. The study utilized the Information Integration Theory, which seeks to understand how individuals form judgments and make decisions in everyday life situations by considering different elements such as the valuation of stimuli, the integration of the psychological representation of those stimuli, and the response to the stimuli (Anderson, 1991, 1996, 2008; Muñoz et al., 2017). This subjective valuation process considers the subject’s motivation and the purpose of the task, and the different appraisals are integrated to make explicit responses (Muñoz et al., 2017). Previous research has used this theoretical approach in various fields, including politics and health (Mullet et al., 2021; Muñoz-Sastre & Mullet, 2021). Given the complexity of the study of judgments and the extensive previous experience with the Information Integration Theory, this approach was used in the present study for both the methodological design and the analysis of the results.

In addition, it is important to mention that according to the Departamento Nacional de Estadística (DANE) census (2018), the indigenous population represents 4.42% of the total Colombian population and is organised into 115 indigenous peoples. 67.3% of them live in rural areas, which highlights the importance of territory for these communities. The territory is not only a means of livelihood through agriculture, but also represents a connection to their gods. However, these territories are often targeted by companies seeking to extract natural resources or develop tourism, which is encouraged by Colombian laws (Comisión de la Verdad, 2022) and by actors of the armed conflict due to their strategic location and biodiversity. Therefore, the present study focuses on understanding the willingness of indigenous communities to forgive, as they represent a minority that has been deeply impacted by violence. Their judgments are crucial in the process of building peace and restorative justice.

Indigenous conflict resolution practices are diverse and vary according to each community. For instance, the Wayúu community utilizes the damage compensation system through possessions or services (Gómez, 2015), while the Nasa indigenous community is characterized by non-violence in conflict situations that affect their community (Acosta Oidor et al., 2019; Chaves et al., 2018), seeking to restore harmony in the community rather than implementing a punishment (Dlestikova, 2020).

In indigenous communities, the process of reconciliation between victims and offenders is pursued, and forgiveness is a crucial element of this process. For an offender to be granted forgiveness, they must acknowledge their responsibility, commit to a change in their behaviour, and provide reparation for the damage they caused (Dlestikova, 2020). For the Embera community, forgiveness has religious, spiritual, and individual connotations. According to Beltrán’s (2021) findings, forgiveness is defined as a feeling in which the aggrieved individuals overcome the pain caused by the victimizing events. It is worth noting that forgiveness does not entail forgetting, and the offender must demonstrate no intention of reoffending, it is not enough to simply apologize verbally (Beltrán, 2021).

This study had a greater participation of the Wayuu community. The study originally intended to include other communities, but the public health situation (quarantine for COVID-19) and resistance from community leaders meant that only a few representatives from these communities - Pijao, Nasa, Embera and Kaamash-Hu - agreed to participate.

The Wayuu community lives in a region called La Guajira. It is a dry and arid peninsula that straddles Colombia and Venezuela. For a long time, this community - the largest in the region - resisted the Spanish settlers by taking refuge in geographical areas that were not very attractive from an agrarian and climatic point of view. The Wayuu have always affirmed their autonomy and maintained their customs (Chaves, 1953; Perrin, 1979). The status of women, for example, is very high. They are involved in handicrafts and manage family income and expenditure. Justice is exercised by the Pütchipü’üi (Palabrero). It is a form of community justice that has more to do with mediation and appeasement than with judgement or the administration of punishment. This type of judicial practice, mainly restorative and reparative, which Gómez (2015) labelled the damage compensation system through possessions or services, has been declared a World Intangible Cultural Heritage (Unesco, 2010).

Given the justice practices in the Wayuu community, it was considered interesting to study the willingness of community members to forgive in a familiar, almost archetypal situation: that of the destruction of all or part of a garden’s crop due to the intrusion of a neighbour’s livestock. Our hypothesis, based on the latest studies of forgiveness carried out in Bogotá (López-López et al., 2018; López-López et al., 2013; Pineda-Marín et al., 2019; Pineda-Marín et al., 2018) was that a high percentage of participants from the Wayuu community (perhaps 40%) would express the principled Always Forgive position already found among a significant proportion of Bogotanos (24%). This high percentage would normally contrast with the percentages observed in other communities that have not adopted restorative justice principles to the same degree.

Method

Design

The present study was designed following a factorial design 2 x 2 x 3 (Severity of Consequences x Carelessness x Apology).

Participants

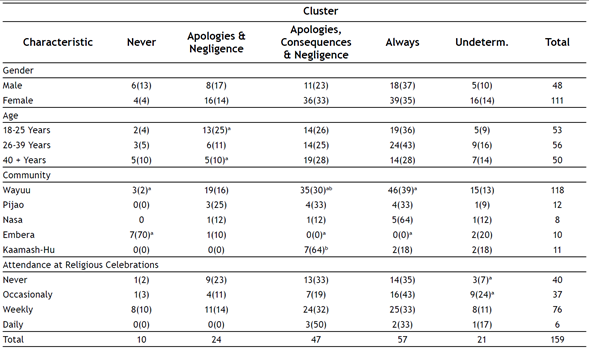

Participants were 159 indigenous adults (30% male) aged 18-76 years (M = 35.45, SD = 13.71) who lived in several regions of Guajira or the department of Choco. 74% belonged to the Wayuu community, 7.5% to the Pijao community, 5% to the Nasa community, 6.3% to the Embera community and 6.9% to the Kaamash-Hu community. Other demographic characteristics are shown on Table 1.

Table 1 Demographic characteristics of the sample. Composition of the clusters

Figures with the same superscript are significantly different, p < .05.

The participation rate was 70%. The main reason expressed for not participating was lack of time. The study complied with the ethical recommendations of the Colombian Psychological Society, i. e., full anonymity was observed and informed consent was obtained from all participants. Since they were (in some cases) not sure of being able to read for themselves, and to understand, the informed consent procedure was explained verbally by the researchers.

Material

The materials consisted of twelve cards describing typical situations in which (a) an orchard was damaged by domestic animals, (b) the orchard owner had a conversation with the animals’ owner, showing the damage done and asking what had happened with the animals, and (c) the animals’ owner gave an explanation and possibly offered to repair the damage done. Each scenario contained three pieces of information, in the following order: (a) the severity of the damage caused (partial damage vs. complete damage), (b) the animal owner’s explanation and apology (the owner acknowledges no responsibility, or the owner acknowledges responsibility for what happened, or the owner acknowledges responsibility and additionally offers to repair the damage), and (c) the level of recklessness of the animal owner (this event occurred only once vs. three times). The scenarios were obtained by orthogonally crossing the levels of these three factors. The design was therefore Severity of Consequences x Carelessness x Apology, 2 x 2 x 3.

Here is an example of a scenario: “David has a large orchard. One morning, he notices that part of the orchard has been destroyed by cows belonging to his neighbour Arturo. David goes to Arturo’s house and asks him to explain what happened. Arturo admits that it was his cows’ fault and apologies to David. This is the first time Arturo’s animals have been in the orchard. If you were David, how willing would you be to forgive Arturo?” Responses were given on an 11-point scale ranging from Not at all (0) to Strongly agree to forgive (10). The response scale measures the degree or level of the dependent variable, which is the willingness to forgive.

Procedure

Data collection took place in 2021, when conditions in the pandemic environment allowed contact with participants. Data collection was carried out following all biosafety criteria recommended by the Colombian Ministry of Health.

The procedure followed Anderson’s (1996, 2008) recommendations for this type of study. Participants were tested individually, near their homes, in an outdoor, quiet and comfortable area. During a familiarization phase, participants were trained to use the response scale based on a few randomly selected scenarios. During the subsequent experimental phase, participants responded to all scenarios. As the indigenous governors had authorized participation, there was no objection from the people. The only cases of non-participation were due to being underage or having to attend to daily activities outside the community.

When the participant was not sure that he/she could read the short texts proposed, the experimenter explained them to him/her until the participant expressed the fact that he/she had understood. Participants took 10 to 20 minutes to complete the assessments. No participants complained about the number of vignettes or the credibility of the proposed situations.

Results

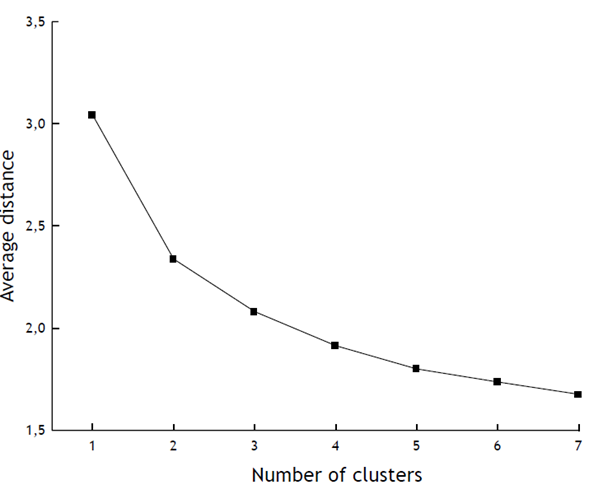

Because we were interested in detecting qualitatively diverse positions among the participants, namely a Quality of Information and Remorse position, a cluster analysis, employing the K-means procedure promoted by Hofmans and Mullet (2013) was performed on the raw data. Different cluster solutions were run and tested. That procedure advocated by Mullet et al. (2016), was also applied on the raw data. Different cluster solutions were tested. Figure 1 shows the decrease in the average distance from the centroid as a function of the number of clusters considered. The five-cluster solution was retained because it offered the most interpretable clusters. It partitioned the sample into five groups of 57, 47, 24, 21, and 10 participants.

Figure 1 Decrease in the average distance from the centroid as a function of the number of clusters considered

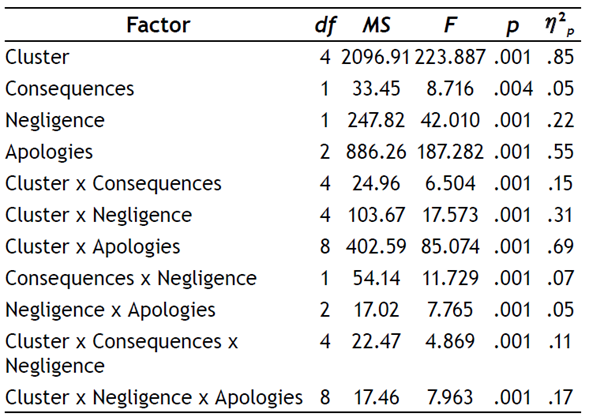

An overall ANOVA was conducted with a design of Cluster x Severity of Consequences x Negligence x Apologies, 5 x 2 x 2 x 3. Owing to the great number of comparisons, the significance threshold was set at .001. As shown on Table 2, the cluster effect and five of the six two-way interactions involving Cluster were significant.

The first cluster (N = 10, 6% of the sample, not shown) was the expected Almost never forgive cluster. All ratings were low (M = 1.17, SE = 0.28), and no effect was detected. As can be observed on Table 1, the members of the Embera community were more often in this cluster (70%) than the members of the Wayuu community (2%).

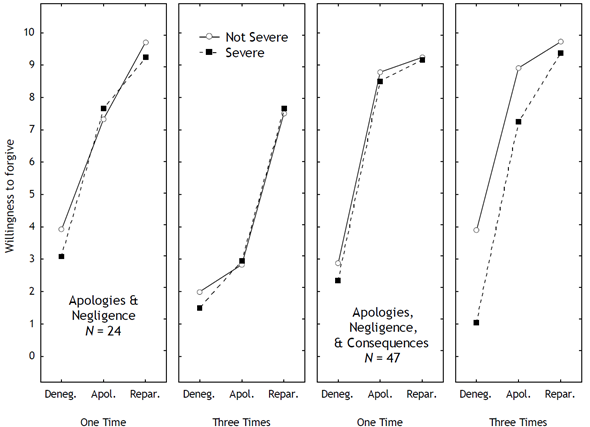

The second cluster (N = 24, 15%) was called Apologies and Negligence. As shown in Figure 2 (left panels), willingness to forgive was considerably higher when apologies were present (M = 8.53, SE = 0.58) rather than absent (M = 2.63, SE = 0.65), n²p = .79. It was lower when there was evidence of carelessness (M = 4.08, SE = 0.66) than when there was no evidence of carelessness (M = 6.83, SE = 0.64), n²p = .65. In addition, willingness to forgive was lower when simple apologies (without offers of reparation) were presented in the context of evident carelessness (M = 2.90, SE = 0.54) than when simple apologies were presented in the context of no evident carelessness (M = 7.50, SE = 0.61), n²p = .40. Younger participants (25%) were more often in this cluster than older participants (10%).

Figure 2 Willingness to forgive judgments are on the vertical axis. The three levels of the apologies factor are on the horizontal axis (Denegation of any responsibility, Simple apologies, and Apologies and offers to repair the damage). The two curves correspond to the two levels of severity of the damage. The two panels on the left correspond to the Apologies and Negligence position. The two panels on the right correspond to the Apologies, Negligence, and Consequences position

The third cluster (N = 47, 30%) was called Apologies, Consequences, and Negligence. As shown in Figure 2 (right panels), willingness to forgive was, as in the preceding case, considerably higher when apologies were present (M = 9.38, SE = 0.30) rather than absent (M = 2.54, SE = 0.47), n²p = .90. It was lower when the consequences were severe (M = 6.28, SE = 0.39) than when they were not severe (M = 7.24, SE = 0.40), n²p = .37. In addition, the effect of the severity of consequences was stronger (7.51 - 5.89 = 1.62) when there was evidence of carelessness than when there was no evidence of carelessness (6.96 - 6.67 = 0.29), n²p = .28. The members of the Embera community were less often in this cluster (0%) than the members of the Wayuu community (30%), who were, in turn, less often in this cluster than the members of the Kaamash-Hu community (64%).

The fourth cluster (N = 57, 36% of the sample, not shown) was the expected Almost always forgive cluster. All ratings were high (M = 9.25, SE = 0.12), and no effect was detected. As can be observed on Table 1, the members of the Embera community were less often in this cluster (0%) than the members of the Wayuu community (38%). The fifth cluster (N = 21, 13%, not shown) was called Undetermined because ratings were always close to the middle of the response scale (M = 6.23, SE = 0.19), and no effect was detectable.

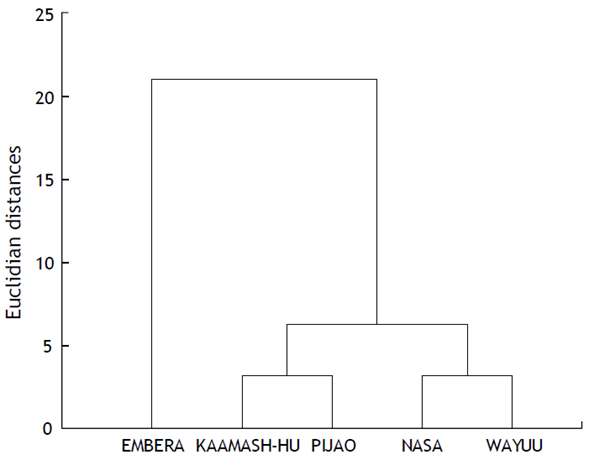

Figure 3 shows the Euclidian distances between the patterns of responses of the five ethnic groups. The main opposition is between the Wayuu and the Nasa, on the one hand, and the Embera, on the other hand.

Discussion

For 87% of the participants, a clear position regarding willingness to forgive in various familiar circumstances was evident. A minority of participants, however, preferred not to express themselves. Similar subgroups of undecided participants have been found in other studies in Colombia and elsewhere (e.g., Armange & Mullet, 2016; López López et al., 2013, 2018) and the reasons for this indecision have been analyzed (Johnston Conover et al., 2002).

Wayuu community expressing an Almost always forgive position was high. Of those who expressed a clear position (89%), 44% actually expressed this position. The only group that shows a similar forgiveness philosophy is the Nasa (71%), although they were represented by only a few members. Thus, there is a clear convergence between the results of this study and the anthropological observations that led to Unesco’s decision to consider the justice system of this community as an unalterable heritage (Unesco, 2010). This convergence is reinforced by the fact that (a) comparatively few Wayuu have expressed the radically opposite position of Never forgive (less than 3%), and that (b) a majority of Wayuu (51%) are willing to forgive whenever the circumstances are reasonably favorable, especially whenever the perpetrator at least apologize and behaves responsibly (carefully).

There is also convergence between the results of this study and the few anthropological observations made among members of the Nasa community. According to Dlestikova (2020), in cases of common transgressions, the Nasa prioritize restoring communal harmony over determining a level of punishment; that is, they tend to prioritize forgiveness over retribution. More generally, they tend to take a nonviolent stance in situations where conflict would expose the community (Acosta Oidor et al., 2019; Chaves et al., 2018). Furthermore, the results observed among the Embera remain surprising and cannot be attributed to an alternative definition of forgiveness that would be substantially different from that in other communities (Beltran, 2021).

Limitations

The main limitation of the study is of course the small number of participants from the Pijao, Nasa, Embera and Kaamash-Hu communities. Future studies should be conducted among members of these communities, as the few fragile results observed in the present study reflect potentially very different philosophies regarding forgiveness among the communities.