Services on Demand

Journal

Article

Indicators

-

Cited by SciELO

Cited by SciELO -

Access statistics

Access statistics

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in

SciELO

Similars in

SciELO -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Revista Colombiana de Ciencias Pecuarias

Print version ISSN 0120-0690

Rev Colom Cienc Pecua vol.28 no.3 Medellín July/Aug. 2015

https://doi.org/10.17533/udea.rccp.v28n3a8

ORIGINAL ARTICLE

doi: 10.17533/udea.rccp.v28n3a8

Genetic diversity of domestic pigs in Tierralta (Colombia) using microsatellites¤

Diversidad genética del cerdo doméstico en Tierralta (Colombia), usando microsatélites

Diversidade genética do porco doméstico em Tierralta (Colômbia), usando microssatéliteso

Enrique Pardo1*, Lic Biol Qca, PhD; Teodora I Cavadía1, Lic Biol, MSc; Iván Melendez2, Biol, MSc.

1Área de Genética, Departamento de Biología, Universidad de Córdoba, Montería, Córdoba, Colombia.

2Departamento de Biología, Área de Genética, Universidad de Pamplona, Pamplona, Norte de Santander, Colombia.

*Corresponding author: Enrique Pardo. Departamento de Biología, Universidad de Córdoba, Montería. Colombia. Email: epardop@correo.unicordoba.edu.co

Received: May 15, 2014; accepted: November 7, 2014

Summary

Background: according to several authors, domestic pigs come from different wild boar populations with varied geographic distribution and are grouped in the genus Sus. Pig domestication occurred gradually. The first animals were small and gathered in small numbers. Several civilizations domesticated this animal as an important source of protein. Tierralta, in Córdoba province, has a large population of domestic pigs, which are a mixture of creole and other breeds. The genetic characterization of populations is used to check the status of genetic diversity, a conclusive element in determining breeding strategies and genetic conservation programs. PCR is the most commonly used technique for studying highly polymorphic markers, such as microsatellites or SSRs. The use of microsatellites is a powerful tool in genetic studies. They have been used for characterization studies of genetic diversity, genetic relationships between populations, paternity testing, inbreeding and genetic bottlenecks. Objective: the purpose of this study was to determine the genetic diversity of domestic pigs in Tierralta (Córdoba, Colombia) using 20 microsatellites. Methods: fifty four samples were studied. Twenty microsatellites recommended by the FAO/ISAG for swine biodiversity studies were used. Results: all the microsatellites were polymorphic, and were detected between 3 (SW911) and 14 (TNFB) alleles (the average number was 6.9 alleles) and a total of 138 alleles were detected. Average expected heterozygosity was 0.5259 and the observed heterozygosity was 0.5120. PIC values ranged from 0.3212 to 0.7980 for loci SW2410 and IFNG, respectively. Conclusions: the results suggest that the analyzed population represents a group with high genetic diversity.

Keywords: genetic variation, Hardy-Weinberg, probability of exclusion, Sus scrofa domestica.

Resumen

Antecedentes: varios autores concuerdan en afirmar que los cerdos domésticos provienen de diferentes poblaciones de jabalí salvaje con distinta distribución geográfica y se agrupan en el género Sus. Es aceptado que la domesticación del cerdo, ocurrió de manera lenta y progresiva y que los primeros animales eran pequeños, se reunían en grupos poco numerosos. La preferencia para la domesticación de estos animales en varias civilizaciones, se debió a que ellos representaban una importante fuente proteica. El departamento de Córdoba es una de las regiones de Colombia con mayor población de cerdo doméstico, formada en su mayoría por la mezcla de la raza criolla con otras razas. La caracterización genética de las poblaciones, permite comprobar el estado de la diversidad genética, elemento concluyente en la determinación de estrategias de crianza y de programas genéticos de conservación. La PCR es la técnica más utilizada para el estudio de marcadores extremadamente polimórficos como son los microsatélites o SSRs. Los microsatélites son una poderosa herramienta para estudios genéticos, los cuales han sido utilizados para estudios de caracterización y diversidad genética, relaciones genéticas entre poblaciones, pruebas de paternidad, consanguinidad, cuellos de botella genéticos, entre otros. Objetivo: el objetivo del presente estudio fue determinar la diversidad genética de la población de cerdo doméstico en Tierralta (Córdoba, Córdoba). Método: fueron estudiadas 54 muestras de este grupo. Se usaron 20 microsatélites de los recomendados por la FAO/ISAG para estudios de biodiversidad porcina. Resultados: se determinó que todos los microsatélites utilizados resultaron polimórficos y se detectaron entre 3 (SW911) y 14 (TNFB) alelos, con un número medio de alelos de 6,9 y un total de 138 alelos. La heterocigosidad media esperada fue 0,5259 y la observada 0,5120. Los valores del PIC oscilaron entre 0,3212 y 0,7980 para los loci SW2410 y IFNG, respectivamente. Conclusión: los resultados sugieren que la población de cerdos analizada, representa un grupo con alta diversidad genética.

Palabras clave: Hardy-Weinberg, probabilidad de exclusión, Sus scrofa domestica, variación genética.

Resumo

Antecedentes: vários autores concordam em afirmar que os porcos domésticos vêm de diferentes populações de javalis com distribuição geográfica variada e estão agrupados no gênero Sus. Aceita-se que a domesticação ocorreu lenta e gradualmente e que os primeiros animais eram pequenos e que eles se reuniram em pequenos números. A preferência para a domesticação desses animais em várias civilizações deveu-se ao fato de que eles eram uma importante fonte de proteína. O departamento de Córdoba é uma das regiões com o maior número de porcos domésticos, composto principalmente da raça crioulo misturado com outras raças. A caracterização genética de populações nos permite verificar o estado da diversidade genética, um elemento conclusivo para determinar estratégias de melhoramento e programas de conservação genética. A PCR é uma das técnicas utilizadas no estudo de marcadores polimórficos, como microssatélites ou SSR. Os microssatélites são uma ferramenta poderosa para estudos genéticos, que tem sido usado para estudos de caracterização da diversidade genética, relações genéticas entre populações, testes de paternidade, endogamia e gargalos genéticos, entre outros. Objetivo: o objetivo deste estudo foi determinar a diversidade genética do porco doméstico em Tierralta (Córdoba, Colombia) utilizando-se 20 microssatélites. Método: foram estudados 54 amostras neste grupo. Foram usados 20 microssatélites recomendado pela FAO/ISAG para estudos de biodiversidade suína. Resultados: foram utilizados vinte microssatélites recomendados pela FAO/ISAG para estudos de biodiversidade suína. Determinou-se que todos os microssatélites utilizados foram polimórficos e foram detectados entre 3 (SW911) e 14 (TNFB) alelos, com um número médio de 6,9 alelos e um total de 138 alelos. A heterozigosidade média esperada foi de 0,5259 e o observado foi de 0,5120. Os valores PIC variaram entre 0,3212-0,7980 para loci SW2410 e IFNG, respectivamente. Conclusões: os resultados sugerem que se trata de uma população significativamente diversa.

Palavras chave: Hardy-Weinberg, probabilidade de exclusão, Sus scrofa domestica, variação genética.

Introduction

The domestic pig is a mammal belonging to the order Artiodactyla, suborder Suinae, family Suideos, subfamily Suinae. According to several authors domestic pigs evolved from different wild boar populations with varied geographical distribution and are grouped in the genus Sus. (Laguna, 1998a; Rotschild and Ruvinsky, 1998). Pig domestication occurred gradually. The first animals were small and they gathered in small numbers. Although there is no unanimous consensus about this, it is estimated that domestication began in Europe between the years 7000 and 3000 BC. Before the discovery of America in 1492, this continent lacked most of the current domestic species. These species arrived at the Antilles and migrated from there to the rest of the continent. Columbus brought pigs on his second voyage (Crossby, 2003). Years later, R. Bastidas, founder of Santa Marta (Colombia) in 1525, also brought 300 pigs (Peña and Mora, 1977). Cordoba region has a high number of domestic pigs (Sus scrofa domestica), which are a mixture of creole and other breeds.

PCR is the most commonly used technique for studying highly polymorphic markers such as microsatellites or SSRs (Simple Sequence Repeats). It is a powerful tool for genetic studies and has been used to characterize genetic diversity, genetic relationships between populations, influence of one breed over another (admixture), paternity testing, inbreeding, and genetic bottlenecks (Martinez et al., 2005, Quiroz et al., 2007). Microsatellites are sequences of 2-6 tandemly repeated nucleotides, also known as short tandem repeats (STRs) or simple sequence repeats (SSRs). They are spread widely throughout the genome but their distributions within chromosomes is not uniform, and are commonly found in lower abundance in subtelomeric regions (Koreth et al., 1996). They can be found in both coding and non-coding regions (Huan et al., 2009), although they are mostly present in non-coding regions of eukaryotes (Xu et al., 2008).

Accounting for the genetic variability of domestic pigs is important in developing breeding strategies, genetic conservation programs, and in establishing a baseline for comparison with existing populations. The aim of this study was to provide information on the state of genetic diversity of domestic pigs (Sus scrofa domestica) in Tierralta, Córdoba by using 20 microsatellites to calculate heterozygosities per locus, average heterozygosity, and compare this information with other populations with the same genetic markers.

Material and methods

Location

Tierralta, Córdoba (8° 10' 34” North and 76° 03' 46” West), Colombia.

Sample collection

Hair samples from 54 individuals were collected. The specimens came from family farms and did not have genealogical records.

Experimental procedure

DNA was extracted from each sample using a modification of the protocol described by Sambrook et al. (2001). DNA was extracted from the hair bulb by protein digestion with proteinase K and phenolchloroform purification.

A total of 20 microsatellites were used in this study. Among these, four were in the list of markers recommended by FAO/ISAG (2011). The selection of the remaining loci represented most of the pig genome. Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR) amplified each marker in the 54 samples collected. The PCR was performed in a thermocycler (MyCycler Bio-Rad®, Munchen, Germany) and consisted of a denaturation step at 95 °C for 5 min followed by 35 cycles of 30 s denaturation at 94 °C, 30 s at optimal temperature for annealing (56, 58, 60, and 62 °C, depending on the marker) and 50 s of extension at 72 °C. Finally, an extension phase of 5 min at 72 °C was applied. PCR products were analyzed by electrophoresis on a 12% polyacrylamide gel using a DNA Sequence MINI-PROTEAN II (Bio-Rad Laboratories GmbH) vertical chamber. The electrophoresis stage ran between 3-5 hours depending on the microsatellite size at constant 15 W and fluctuating voltage from 300 to 400 V. The sample subjected to electrophoresis consisted of amplified DNA and loading buffer (bromophenol blue 2% w/v dissolved in MiliQ water). The markers were visualized by exposing the gel to white light after staining with silver nitrate (Qiu et al., 2012). An allelic ladder was used to determine the size of the alleles, and allele assignment involved fitting a linear regression curve developed from migration distances of known-size fragments. Software and statistical analysis: heterozygosities and FIS were measured with GENETIX software v. 4.05 (Belkhir et al., 2004). Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium (HW) was calculated using GENEPOP program v. 3.3. (Raymond and Rousset, 2001). Additionally, Polymorphic Information Content (PIC) of each microsatellite was measured by CERVUS program v. 3.0.3. (Kalinowski et al., 2007). Allelic richness and inbreeding coefficient were obtained with FSTAT program v. 2.9.3.2 (Goudet, 2002).

Results

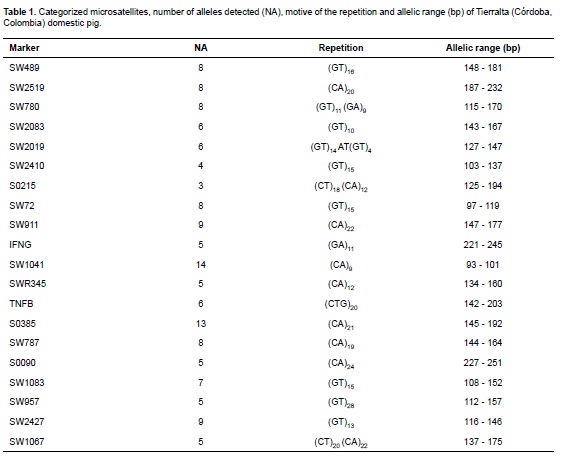

Results showed a high degree of polymorphism in all microsatellites, as evidenced by the average number of alleles per locus. A total of 138 alleles were detected, ranging between 3 (SW2410) and 14 (IFNG) alleles per locus (Table 1).

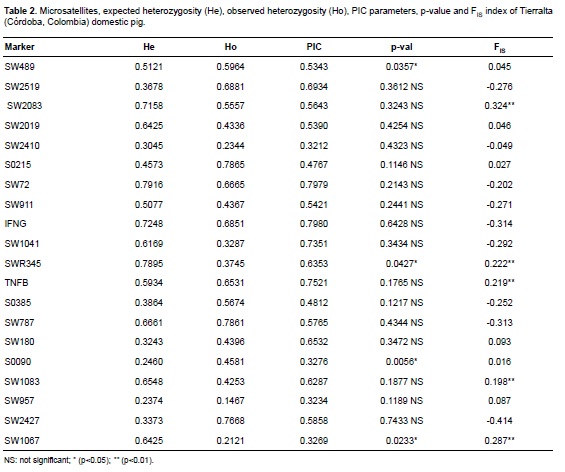

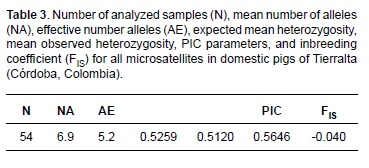

The polymorphic information content (PIC) obtained (Table 2) ranged from 0.3212 (SW2410) to 0.7980 (IFNG). The FIS statistic varied between -0.414 and 0.324 for markers SW2427 and SW2083, respectively. Eleven of the 20 markers were positive and 9 were negative. The FIS average was -0.040 (Table 3). According to statistical FIS, 11 markers were positive (indicating excess of homozygotes) and 9 were negative. The average FIS indicates low exogamy with a slight excess of heterozygotes. These values correspond to markers with the lowest and highest number of alleles. The high degree of polymorphism is also evidenced by the average number of alleles found in the population (Table 3).

According to Botstein et al. (1980), of the 20 markers analyzed, 14 can be considered very informative (PIC>0.5) and six markers were moderately informative (PIC>0.25) when detecting genetic variability. The average value of PIC in our study was lower compared with previously published data in a study of European breeds (Vicente et al., 2008) and similar to those reported for Mamellado of Uruguay and native Chinese pigs (Li et al., 2004; Castro et al., 2007). Sixteen of the microsatellites were in Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium, so the population is genetically stable (Table 2). This may show that that any new animals introduced to this population likely come from populations with the same genetic heritage as the population sampled, or that mating within the population occurred at random (with respect to the markers considered). Four loci showed a significant deviation from HW equilibrium (SW489, SWR345, S0090, and SW1067), revealing an excess of homozygotes. Homozygous excess in a population could be a result of inbreeding events (Allendorf and Luikart, 2007). However, inbreeding affects the entire genome equally, so one would expect that all markers employed would show homozygous excess, which is not the case here. Similarly, the Wahlund effect could occur, (a possible genetic structure subdivision). If so, it would mean that there are marked differences between pig populations close to the markers (SW489, SWR345, S0090, and SW1067), but not for the other markers. If these differences between markers were not removed it is because the existing gene flow between neighboring populations is limited (a characteristic not shown by the other markers), or that such microsatellites (SW489, SWR345, S0090, and SW1067) are linked to genes subject to natural selection acting differentially on a micro or macrospatial level. Mean observed heterozygosity (51.20%) and mean expected heterozygosity (52.59%; Table 3) show a high degree of variability. These values are similar to those reported in Denmark and the Netherlands and are outweighed by those reported in China, Brazil and Thailand (Sancristobal et al., 2006; Fang et al., 2009; Gama et al., 2013). The mean number of alleles per locus and the allelic richness (Table 3) indicate that this population exhibits some degree of variability. FIS values (Tables 2 and 3) show that the studied population is homogeneous in its genetic characteristics. Because this is the first work attempting to determine genetic diversity of these pigs there is no prior information enabling us to explore the possibility of loss of genetic diversity through time. However, one cannot exclude the possibility of inbreeding of this species. The results of this study support the conclusion that the microsatellites used reveal a high degree of polymorphism. The high percentage of markers with high PIC facilitates the implementation and optimization of this technique for genealogical research and assignment of individuals to populations. The levels of observed and expected heterozygosity found indicate that the domestic pig (Sus scrofa domestica) in Tierralta, Córdoba has a high degree of genetic variability.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare they have no conflicts of interest with regard to the work presented in this report.

Notes

¤To cite this article: Pardo E, Cavadía TI, Melendez I. Genetic diversity of domestic pigs in Tierralta (Colombia) using microsatellites. Rev Colomb Cienc Pecu 2015; 28:272-278.

References

Allendorf FW, Luikart G. Conservation and the genetics of populations. Massachusetts: Blackwell; 2007. [ Links ]

Belkhir K, Borsa P, Goudet J, Chikhi L, Bonhomme F. GENETIX v.4.05 logiciel sous Windows pour la genetique des populations. Laboratoire Ge'nome, Populations, Interactions CNRS UMR 5000, University of Montpellier II, Montpellier. 2004. [ Links ]

Botstein D, White RL, Skolnick M, Davis RW. Construction of a genetic linkage map in man using restriction fragment length polymorphisms. Am J Hum Genet 1980; 32:314-331. [ Links ]

Castro G, Santandreu A, Ronca F, Lozano A. La cría de cerdos en asentamientos urbanos y periurbanos de Montevideo (Uruguay). En: Serie Cuadernos de Agricultura Urbana ''Porcicultura urbana y periurbana en ciudades de América Latina y el Caribe''. Lima, Perú. ISBN: 978-9972-668-11-1; 2007. p.34-39. [ Links ]

Chang WH, Chu HP, Jiang YN, Li SH, Wang Y, Chen CH. Genetic variation and phylogenetics of Lanyu and exotic pig breeds in Taiwan analyzed by nineteen microsatellite markers. J Anim Sci 2009; 87:1-8. [ Links ]

Fang M, Hu X, Jin W, Li N, Wu C. Genetic uniqueness of Chinese village pig populations inferred from microsatellite markers. J Anim Sci 2009; 87:3445-3450. [ Links ]

FAO. Molecular genetic characterization of animal genetic resources. Animal Production and Health. Guidelines 9. Rome; 2011. [ Links ]

Gama L, Martínez AM., Carolino I, Landi V, Delgado JV, Vicente AA, Vega-Pla JL, Cortés O, Sousa C, Consortium B. Genetic structure, relationships and admixture with wild relatives in native pig breeds from Iberia and its islands. Genet Sel Evol 2013; 45:18-32. [ Links ]

Goudet J. FSTAT version 2.9.3.2. Available from jerome.goudet@ie.zea.unil.ch, via email. Institute of Ecology, UNIL, CH-1015, Lausanne, Switzerland. 2002. [ Links ]

Groenen M, Archibald A, Uenishi H, Tuggle C, Takeuchi Y, Rothschild M. Analyses of pig genomes provide insight into porcine demography and evolution. Nature 2012; 491:393-398. [ Links ]

Huan G, Cai S, Yan B, Chen B, Yu F. Discrepancy variation of dinucleotide microsatellite repeats in eukaryotic genomes. Biol Res 2009; 42: 365-375. [ Links ]

Kalinowski ST, Taper ML, Marshall TC. Revising how the computer program CERVUS accommodates genotyping error increases success in paternity assignment. Mol Ecol 2007; 16:1099-1106. [ Links ]

Koreth J, O'leary JJ, Mcgee ODJ. Microsatellites and PCR genomic analysis. J Pathol 1996; 178:239-248. [ Links ]

Laguna E. El cerdo Ibérico en la colonización y poblamiento porcino de América. Sólo Cerdo Ibérico. AECERIBER. Zafra. Badajoz; 1998a. p.7-13. [ Links ]

Li SJ, Yang SL, Yang SH., Zhao SH, Fan B, Yu M, Wang HS., Li MH, Liu B, Xiong TA, Li K. Genetic diversity analyses of 10 indigenous Chinese pig populations based on 20 microsatellites. J Anim Sci 2004; 82:368-74. [ Links ]

Martínez A, Pérez-Pineda E, Vega-Pla J, Barba C, Velásquez F, Delgado J. Caracterización Genética del cerdo Criollo Cubano con Microsatélites. Arch Zootec 2005; 54:369-375. [ Links ]

Megens HJ, Crooijmans R, Cristobal MS, Hui X, Li N, Groenen MM. Biodiversity of pig breeds from China and Europe estimated from pooled DNA samples: differences in microsatellite variation between two areas of domestication. Genet Sel Evol 2008; 40:103-128. [ Links ]

Peña M, Mora C. Historia de Colombia. Bogotá: Editorial Norma; 1977. [ Links ]

Qiu S, Chen J, Lin S, Lin X. A comparison of silver staining protocols for detecting DNA in polyester-backed polyacrylamide gel. Braz J Microbiol 2012; 43(2):649-652. [ Links ]

Quiroz J, Martínez A, Marques J, Calderón J, Vega-Pla J. Relación genética de la vaca Marismeña con algunas razas andaluzas. Arch Zootec 2007; 56 Suppl 1:449-454. [ Links ]

Raymond M, Rousset F. GENEPOP (ver. 3.3): a population genetics software for exact test and ecumenicism. J Hered 2001; 86:248-249. [ Links ] Rothschild MF, Ruvinsky A. The genetics of the pig. Cabi Publishing. Cab International; 1998. [ Links ]

Sancristobal MC, Chevalet CS, Haley R, Joosten AP, Rattink B, Harlizius MAM, Groenen Y, Amigues MY, Boscher G, Russell A, Law R, Davoli V, Russo C, Désautés L, Alderson E, Fimland M, Bagga JV, Delgado JL, Vega-Pla AM, Martinez M, Ramos P, Glode NJ, Meyer GC, Gandini D, Matassino GS, Plastow KW, Siggens G, Laval AL, Archibald D, Milan K, Hammond R, Cardellino R. Genetic diversity within and between European pig breeds using microsatellite markers. Anim Genet 2006; 37(3):189-198. [ Links ]

Sambrook J, Russell DW. Molecular Cloning: a laboratory manual. 3rd ed. New York: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 2001. [ Links ]

Vicente AA, Carolino MI, Sousa MC, Ginja C, Silva FS, Martínez AM, Vega-Pla JL, Carolino N, Gama LT. Genetic diversity in native and commercial breeds of pigs in Portugal assessed by microsatellites. J Anim Sci 2008; 86:2496-2507. [ Links ]

Xu Z, Gutierrez L, Hitchens M, Scherer S, Sater AK, Wells DE. Distribution of polymorphic and non-polymorphic microsatellite repeats in Xenopus tropicalis. Bioinform Biol Insights 2008; 2:157-169. [ Links ]