Introduction

In some species, during the nursing period lactating females occasionally nurse offspring that are not their own, a behavior referred to as allonursing (Riedman, 1982; Hoogland et al., 1989). Allonursing can contribute to maternal welfare, udder health and milk quality by reducing painful milk pressure and udder infections, which maximizes milk production (Roulin, 2002).

One of the great benefits for allosucklers is the compensation of some important deficiencies at birth, such as low birth weight or maternal milk insufficiency (Víchová and Bartos, 2005). Allosucklers may also gain immunological benefits by suckling from more than one nursing mother thus obtaining various specific immunological compounds, which improve resistance against pathogens (Roulin and Heeb, 1999). Besides this, allosucklers can also ingurgitate extra milk and thereby obtain additional energy (Packer et al., 1992). However, allonursing may imply costs, because lactation is the most energetically expensive stage in mammals (Clutton-Brock et al., 1989). In addition, milk transfer could reduce the amount of nutrients available to the current calf (Mendl, 1988) and allonursing can spread pathogens to a number of calves simultaneously (Roulin and Heeb, 1999).

Some non-mutually exclusive hypotheses have been proposed to explain why lactating females nurse alien offspring: misdirected parental care (Packer et al., 1992); reciprocity (Ekvall, 1998; Engelhardt et al 2015; Glonekov et al., 2016); kin selection (Pusey and Packer, 1994; Ekvall, 1998; Eberle and Kappeler, 2006; Engelhardt et al., 2016); evacuation of leftover milk (Riedman and Le Boeuf, 1982; Wilkinson, 1992); inexperience of females (Murphey et al., 1991, 1995), and milk theft (Murphey et al., 1995; Maniscalco et al., 2007; Zapata et al.,2009; Engelhardt et al., 2014; Glonekov et al., 2016).

In buffaloes, the allonursing behavior was first observed in a feral herd of Carabao buffalos (Tulloch, 1979) and was also subsequently reported by Murphey et al. (1991; 1995), Paranhos da Costa et al. (2000), Andriolo et al. (2001) and Madella-Oliveira et al. (2010). The effects of calf sex and birth order in buffaloes can decisively influence social interactions during sucking, promoting differential development among calves (Paranhos da Costa et al., 2000). In the Iberian red deer (Cervus elaphus hispanicus), the comparison between hind milk production (MP) and allosucking frequency shows that the percentage of allosucking bouts increases as the MP of the nursing mothers decreases (Landete-Castillejos et al., 2000).

The objective of this study was to evaluate the potential effects of the calf sex and parity order (PO) on nursing behavior, DMP, and TMP of buffalo cows.

Materials and methods

Ethical considerations

The experimental protocol was reviewed and approved by the Ethics Committee on Animal Use of Universidade Estadual do Norte Fluminense Darcy Ribeiro, Brazil (approval number: 262/2014)

Location and animals

The study was conducted at Cataia farm in São Francisco do Itabapoana, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil (21º18’07” S and 40º57’41” W, at an altitude of 8 meters above sea level). In this study, outbred Murrah, Jaffarabadi and Mediterranean females (n= 35; aged 3 to 12 years old) and their calves were investigated. The group included primiparous (n= 2) and multiparous females (n= 33). Calves (15 males and 20 females) included in the study were all born in March (n= 14), April (n= 9) and May (n= 12).

Dams and calves were individually identified with yellow oil paint, with ordinary numbers painted on the hindquarters. Matching numbers were assigned to the cow and calf; so they could be identified from a distance. Plastic earrings were put on the animals, so that they were permanently identified. The animals were habituated to the horseback observer inside pasture for at least 15 days before beginning data collection. During this period, the observer conducted the training using a protocol. Following the farm routine, each cow and her calf were allocated for 15 days in a maternity pasture system (separated from other females). Milking began at 4:00 h, when females were manually milked in the presence of their calves. After milking, around 6:00 h, the herd was conducted to the pasture (measuring 60 hectares), where all females remained with their calves until 12:00 h. The stocking rate used was 0.73AU/ha. The herd was removed at 12:00 h and the mothers were then placed in a pasture away from their calves.

Data were collected during three days at the beginning of each month (May to November). Observations were direct and continuous between 6:00 and 12:00 h (Martin and Bateson, 1986). The observer was in a distance of around 10 m from the animals. A binocular was used for identification of numbers at a distance, to avoid interference with the behavior of the animals. All animals were in sight at all times. A timer was used to register nursing time, followed by identification of the cow and calf. The timing of the start and end of nursing was registered in an audio recorder. Nursing was considered to begin from the moment the calf attached to the teat with a suckling movement.

Nursing behavior was characterized into three types: 1) Isolated filial nursing (IFN): when the female was nursing its own calf; 2) Collective filial nursing (CFN): when a female began nursing its own calf as well as one or more alien calves; and 3) Non-filial nursing (NFN), when a female was nursing one or more calves that were not hers.

To study the effect of nursing behavior on daily milk production (DMP) and total milk production (TMP), females were grouped into four categories: 1) Non-permissive (NP): females that did not allow any kind of nursing; 2) Filial permissive (FP): females that allowed IFN; 3) Filial and collective filial permissive (FCFP): females that allowed two types of nursing behavior: IFN and CFN; and 4) Filial, collective filial and non-filial permissive (FCFNFP): females that allowed three types of nursing behavior: IFN, CFN and NFN.

Milk was collected from each cow and quantified during the same three days per month when nursing behavior was observed. DMP was registered in kilograms. TMP was defined as the amount of milk (kg) produced throughout the lactation period (270 days).

Statistical analysis

The data were analyzed using SAS (SAS Institute Inc, Cary, NC, USA). Frequency of behavior was analyzed with the chi-square test (PROC FREQ). For other data, we used PROC MIXED to fit a linear model for repeated measures. Animal was used as the random effect, while nursing behavior, sex of calf, month of observation and parity order were fixed effects. Results are reported as least square means (LSMEANS) with standard error (SE) given by the PROC MIXED. We used p≤0.05 as the level of statistical significance for all tests.

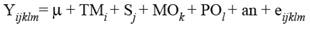

The analysis model was as follows:

Where:

Yijklm = daily milk production and total milk production.

( = general average.

TMi = effect of i th nursing behavior.

Sj = effect of sex of the j th calf.

MOk = effect of kth month of observation.

POl = effect of lth parity order.

an = random effect of animal.

eijklm = random error associated with each observation (N ~ 0.1).

Results

Nursing behavior

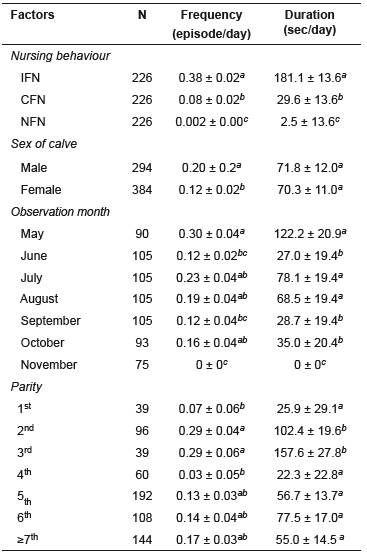

Results in Table 1 show no difference in duration of nursing between buffalo cows with male or female calves. Frequency and duration of nursing behavior for the IFN were significantly greater in relation to CFN and NFN (p<0.05). There was also significant difference in relation to frequency and duration for CFN and NFN (p<0.05). Frequency of nursing was greater in buffalo cows with male calves (p<0.05) than cows with female calves (Table 1).

Differences in frequency and duration of nursing behavior were observed (p<0.05). In May, frequency of nursing behavior was significantly greater compared with June, September and November, and duration of nursing behavior was higher compared with June, September, October and November (p<0.05). A significant difference for frequency of nursing behavior was observed between November and July, August, October (p<0.05). Regarding duration of nursing behavior, a difference was observed between November and the other months (p<0.05).

For the PO among buffalo cows there were statistically significant differences in frequency and duration of nursing behavior (p<0.05). Buffalo cows in 2nd and 3rd PO had greater frequency values of nursing behavior compared with cows in 1st and 4th PO. Regarding duration of nursing behavior, cows in 2nd and 3rd PO had greater values compared with the other POs (p<0.05).

Table 1 Least square means and standard errors (SE) for frequency (episode/day) and duration (seconds/day) of nursing type allowed by buffalo cows, calf sex , month, and parity order (PO).

IFN: isolated filial nursing; CFN: collective filial nursing and NFN: non-filial nursing. N: number of observations. Means followed by different superscript letters (a, b, c) within the same column are significantly different (p<0.05)

Nursing behavior in relation to calf sex and PO

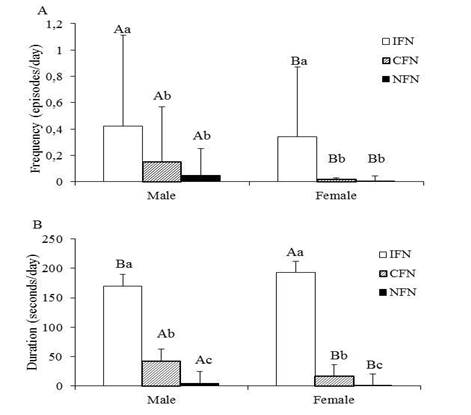

Figure 1 shows that frequency (A) and duration (B) of IFN were significantly greater in

relation to CFN and NFN for both cows with male or female calves (p<0.05). A significant difference was found in relation to duration (B) for CFN and NFN for both cows with male and female calves (p<0.05), but not for frequency.

Results show that frequency (A) of IFN was higher for b cows with male than those with female calves (p<0.05) for each nursing type,. Cows with female calves showed higher values for duration (B) of IFN than those with male calves (p<0.05). Besides, frequency (A) and duration (B) of nursing behavior for CFN were significantly greater in relation to NFN when comparing cows with male versus female calves (p<0.05).

Figure 1 Least square means and standard errors (SE) of the (A) frequency (episode/day) and (B) duration (seconds/day) of each nursing type in relation to sex of the calf. IFN: isolated filial nursing; CFN: collective filial nursing and NFN: non filial nursing. Means with different superscript lowercase letters (a, b, c) show significant difference between nursing types (p<0.05) and means with different superscript uppercase letters (A, B) show significant difference between calf sex with regards to nursing type (p<0.05).

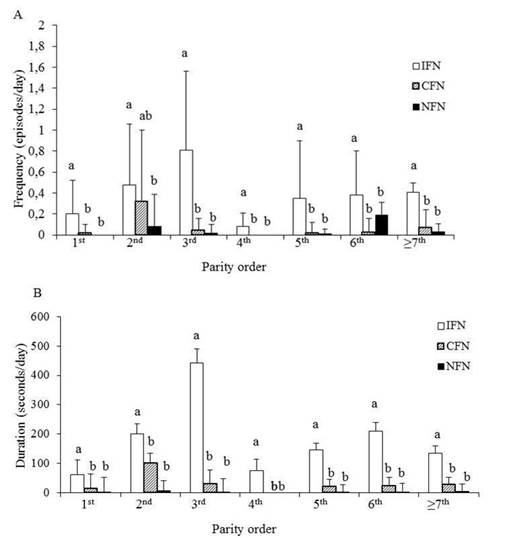

Figure 2 shows the frequency (A) and duration (B) of types of nursing behavior in relation to PO. Except for the second PO, which showed no difference in frequency between IFN and CFN, the frequency and duration of IFN were statistically significant when compared with CFN and NFN for all POs (p<0.05).

Figure 2 Least square means and standard errors (SE) of (A) frequency (episode/day) and (B) duration (seconds/day) of each nursing type in relation to PO. IFN: isolated filial nursing; CFN: collective filial nursing and NFN: non filial nursing. PO: parity order. Means followed by different superscript letters (a, b) are significantly different within each PO (p<0.05).

Factors affecting DMP and TMP: nursing behavior, calf sex, month of observation, and PO.

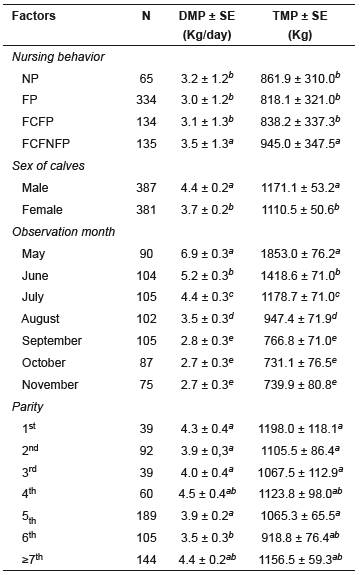

Table2 Least square means and standard errors (SE) of daily milk production (DMP) and total milk production (TMP) in relation to nursing behavior, sex of calves, month of observation and parity order (PO) in buffalo cows.

Nursing behavior: NP: non-permissive; FP: filial permissive; FCFP: filial and collective filial permissive and FCFNFP: filial, collective filial and non-filial permissive. N: number of observations. Means followed by the different superscript letters (a, b, c, d, e) within the same column are significantly different (p<0.05).

The average lactation length for these animals was 213.42 days, with a standard deviation of 66.11 days. The DMP and TMP in relation to nursing behavior, calf sex, month, and PO in cows are shown in Table 2.

The nursing behavior among the 35 buffalo cows was distributed as follows: 3 were NP, 18 FP, 7 FCFP and 7 FCFNFP. As shown, DMP and TMP for cows with FCFNFP were significantly higher compared to those with NP, FP and FCFP (p<0.05).

The DMP and TMP in cows with male calf were significantly greater than that of cows with female calf (P<0.05). During the observed months, the peak of DMP and TMP occurred in May. A decrease in DMP and TMP was observed from June to November (Table 2). The PO among cows did not have an effect on DMP nor on TMP (Table 2).

Discussion

Our results show that collective nursing occurr in buffalo cows, in agreement with other studies (Murphey et al., 1991; 1995; Paranhos da Costa et al., 2000; Andriolo et al., 2001). The IFN values for frequency and duration were higher than CFN and NFN, different than reported by Andriolo et al. (2001), who observed lower values for occurrence and duration of IFN compared to CFN. The low values for collective nursing suggest that farm management interferes with this behavior.

The sex of the calf had an effect on nursing behavior; cows with male calves displayed greater nursing frequency than the ones with female calves, and the frequency and duration of IFN for both were more evident compared with other nursing types (CFN and NFN). Paranhos da Costa et al. (2000) demonstrated that male calves spend greater time in individual filial and in communal non-filial suckling than female calves, which shows greater communal filial suckling, suggesting that the sex of the offspring determines differences in allonursing strategies. In bovine cattle, calf sex had no effect on allosucking frequency and growth gain of the calves (Víchová and Bartŏs, 2005). Zapata et al. (2010) demonstrated that the relationship between allosuckling and the offspring sex was not evident in guanacos ( Lama guanicoe) .

Nursing behavior was more prevalent in May, July and August. Andriolo et al. (2001) showed that suckling behavior varied according to the period of observation. There were increased suckling and decreased filial suckling during the first four months, while a decrease following the gradual process of weaning was observed after the fourth month of nursing. .

Our results showed differences in duration of nursing behavior for cows in 2nd and 3rd PO. The frequency and the duration of IFN were higher when compared with CFN and NFN in all POs, except for the second PO. This indicates the importance of filial nursing to ensure calf nutrition. According to Gloneková et al. (2016), not only female parity affects the probability of successful suckling involving non-filial calves, but also the order of calf suckling (which calf came to suckle first, second, etc.). Thus, other variables should be evaluated, such as age of the calf, age of the nursing female, and hierarchy rank differences between the nursing female and the own mother of the calf.

Our results show that cows that were permissible to all types of nursing behavior (filial, collective filial and non-filial) presented higher DMP and TMP. We thus infer that cows permitting more than one nursing behavior are more stimulated to produce more milk. The cow-calf interaction is important to release oxytocin, a hormone that stimulates milk ejection (Pollack and Hurnik, 1978). In bovine cows, Silveira et al. (1993) demonstrated that the frequency of oxytocin release following suckling was greater in the own group when compared to the alien group, thus the release of oxytocin was affected by mother-young bonds.

In the Iberian red deer, the percentage of allonursing bouts increased with increasing milk production by the nursing hind, but the percentage of allosuckling bouts increased as milk production of the mother decreased (Landete-Castillejos et al., 2000), which shows a difference between nursing behavior of the female and suckling behavior of the calf in relation to milk production.

Furthermore, cows with male compared with female calves showed higher DMP and TMP. This is in agreement with Landete-Castillejos et al. (2005), who showed that for Iberian red deer calves milk yield was greater in dams with males than in dams with females. However, different results were described by Paranhos da Costa et al. (2000) who did not observe a significant relationship between milk production and sex of the calf.

The peak of DMP and TMP occurred in May. From June to November, DMP and TMP decreased. DMP was 6.9 ± 0.3 kg/day in May, but at the beginning of June, production began to decline until November, reaching 2.7 ± 0.3 kg/day. Cerón-Muñoz et al. (2002) showed that production in the first month of lactation was 6.87 kg, declining until the ninth month of lactation, with 3.83 kg. Hurtado-Lugo et al. (2005) obtained high values at the beginning of lactation (4.64 kg to 3.04 ± 1.17 kg). We observed that TMP ranged from 1853.0 ± 76.2 (May) to 739.9 ± 80.8 (November) kg. Sampaio Neto et al. (2001) reported total milk production of 2130.80 ± 535.60 kg, and Junior et al. (2014) found a value of 2218.03 kg.

Our results did not show a definite propensity for a change in the pattern of DMP and TMP related to PO. These results are not in agreement with Sampaio Neto et al. (2001), Afzal et al. (2007) and Pawar et al. (2012), because these studies showed DMP was affected by female parity. The fact that we did not find a difference between PO and DMP and TMP may be related to the quality of the pasture, since pastures are native, with low nutritional quality, and no other supplementary feed was provided to the animals.

In addition, genetic and non-genetic traits should be taken into consideration for milk production parameters. Genetic improvement is related to selection, while non-genetic factors involve management, quantity and quality of feed, and season (Afzal et al., 2007).

In conclusion, our results suggest that nursing behavior is associated with milk production in buffalo cows. Females that are permissible to all types of nursing behavior had the highest DMP and TMP. The sex of calves influenced nursing behavior, DMP and TMP, so cows with male calves displayed more frequent allonursing behavior and produced higher amounts of milk. Females can present different types of nursing behavior, independent from PO, but IFN was more evident in all POs. The DMP and TMP were not affected by PO.