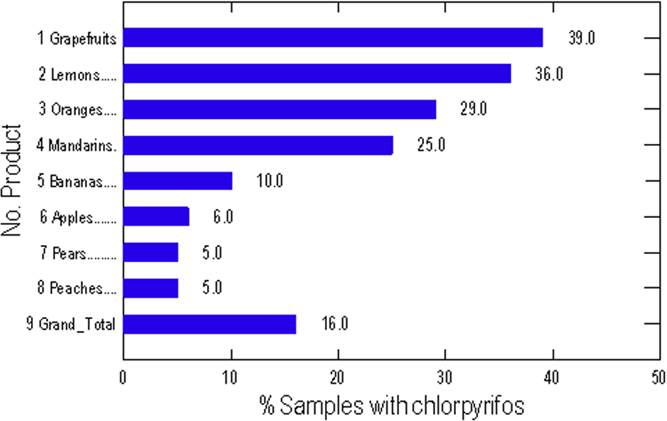

Chlorpyrifos (CPF) is the main pesticide used in Colombia for agriculture and livestock. According to ICA (2021), pesticides registered in Colombia include 28 CPF-based products for use in agriculture, excluding livestock (e.g., Attamix SB). During 2019, a total of 2,692 tons of CPF were commercialized by Colombian importers (ICA, 2019). Most CPF products are ICA class II (moderately) or III (slightly) toxic based on acute toxicity (LD50), but these classifications do not apply to high chronic exposures (manufacturing and use) and chronic ingestion of low concentrations in food. Residue concentrations in agricultural products and considered acceptable before are unsafe now, and CPFs have been recently banned by the European Union (EFSA, 2019) and the United States (USEPA, 2021; Federal Register, 2021). In 2019, before the ban of CPF, the European non-governmental organization “Health and Environmental Alliance” (HEAL) published a summary report showing the percentage of fruits and vegetable with CPF residues in European Union markets (Figure 1) (Heal, 2019). Out of 165 pesticides analyzed, CPF was among the five most detected and the one most frequently exceeding tolerance levels.

Modeling CPF toxicity to human health is a classic example of how the characterization of pesticide exposure can affect regulations. Until 2016, the USEPA used acetylcholinesterase inhibition (AChE), considered the most sensitive biological effect of CPF, to establish that health risks of agricultural products with “tolerable” levels of CPF were low (USEPA, 2016). The rationale was that if acetylcholinesterase was not inhibited, a person was protected from neurotoxicity. However, using new data from unreported findings of industry-funded studies and epidemiological studies, the USEPA (2016) showed that CPF concentrations in umbilical blood lower than AChE inhibition predicted childhood developmental and neurological disorders.

Figure 1 Chlorpyrifos residues in fruits sold in the EU market with the highest frequency of detection.

An early study found a correlation between CPF concentration in maternal and newborn blood with low weight and shorter body length (Whyatt et al., 2005). Children exposed to CPF in utero had lower IQs; psychomotor disorders; cognitive deficits related to learning ability, attention, and working memory; and brain structural alterations visible by Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) (Rauh et al., 2006). The probabilities of a lower Mental Development Index and Psychomotor Development Index were 2.4 and 5 times higher in children with elevated CPF exposures, respectively. At 7 years of age, children’s IQs and working memories decreased by 1.4 and 2.8% for each standard deviation (4.6 pg/g) increase in CPF level (Rauh et al., 2011). When the same children were 6-11 years old, prenatal exposure and brain structure alterations (by MRI) were associated with cognitive and behavioral problems (Rauh et al., 2012). Specifically, children with higher prenatal exposure to CPF had significantly reduced frontal and parietal cortexes. Another study in Costa Rica showed that women (n=387 mother-infant pairs) exposed and excreting CPF metabolites in urine during the third trimester of pregnancy gave birth to children with smaller head circumference in both sexes [-0.66 cm (95% CI: -1.29; -0.04) per log10 unit increase] (Van Wendel de Joode et al., 2014). In a cohort of 140 Costa Rican children aged 6-9, higher urinary CPF concentrations were associated with poorer visual motor coordination, increased prevalence of parent-reported cognitive problems, decreased ability to discriminate colors, and poorer working memory in boys (van Wendel de Joode et al., 2016b). Analogous neurological disorders to those found in children were later reproduced in rats at exact doses lower than inhibited AChE (Berg et al., 2020; Russell et al., 2017).

The CPF is one of many organophosphate and carbamate pesticides to which agricultural workers and inhabitants in Colombia are exposed. After starting work in floriculture, a cohort of 2,951 men and 5,916 women in the Bogotá region were occupationally exposed to 127 different types of pesticides. Symptoms included mental confusion (3.3%) and tremors (2.2%). The prevalence rates of abortion, prematurity, and congenital malformations increased after starting work (Restrepo et al., 1990). In a study of exposure to 1-11 classes of pesticides (but not CPF), all 50 floriculture workers in Cundinamarca, Colombia, had low AChE activity, between 0.056 pH/h and 0.445 pH/h in 27 men, and 0.052 pH/h to 0.264 pH/h in 23 women (Amaya et al. 2008). The AChE tests of 23 workers (20-40 years old) at a banana plantation in Urabá (2008-2009) identified subnormal activity in five people, and other three were at the limit level (Aguirre-Buitrago et al., 2014). Of 204 occupationally exposed workers in four municipalities in Putumayo, 36 (17.6%) had inhibited AChE activity (Varona et al., 2007).

Direct (due to treatment) and indirect (due to loss of productivity) economic costs are associated with CPF exposure. A European Union study determined that 13.0 million IQ points are lost annually, and 59,300 new people are affected by intellectual disability (autism and attention deficit disorders), accounting for 146 billion euros in social costs (Bellanger et al., 2015). The CPF and other organophosphate exposures in the USA created estimated annual losses of billions of dollars in terms of IQ losses and brain development deficits (Attina et al., 2016). Consequently, all use of CPF was banned by the European Union (2020) and USEPA (2021).

In addition to the effects in children, CPF is an endocrine disruptor and breast carcinogen. Wives of pesticide applicators (farmers), who used CPF in their homes had a significantly increased risk of developing breast cancer (hazard ratios=1.4; 95% CI:1.0-2.0); the risk was most pronounced for women diagnosed with premenopausal breast cancer (Engel et al., 2017). Rats fed low doses of CPF for several weeks up to three months had morphological abnormalities in reproductive organs, including changes in mammary glands that were predictive of developing malignant mammary tumors (Nishi and Singh-Hundal, 2013; Ventura et al., 2016). The effect occurs by inducing breast cancer cells through the estrogen receptor Alpha (ERα) on the mammary gland (Ventura et al., 2016). The studies concluded that agricultural workers and their families have the highest exposures, but consumers eating fruits, nuts or other crops sprayed with CPF are also at risk.

CPF shows how pesticide regulation policy can vary greatly depending on which (and how) scientific studies are used to assess health risks. Several aspects of pesticide evaluation should be rectified: (1) All industry-financed studies should be commissioned by regulatory authorities to avoid conflicts of interest. The CPF studies funded by a manufacturer and submitted to the USEPA to renew registrations omitted critical data on toxic effects at doses below those in the application (Sheppard et al., 2020). (2) Laboratories carrying out safety studies should demonstrate the ability to satisfactorily identify all possible adverse effects (i.e., neurodevelopmental disorders for CPF) and the absence of conflicts of interest related with manufacturing, supplying, or applying the pesticide. (3) Regulatory scientists should have access to all documentation known to the company, including confidential data. (4) Epidemiological studies by researchers unaffiliated with the industry must be included in the risk assessment and pesticide authorization processes. (5) Political alignment with industry interests must not be allowed by law to override scientific evaluation processes and decisions, as occurred when the Trump administration (USA) prevented EPA from implementing a ban on CPF in 2017 (USEPA, 2017).

It is discouraging -to say the least- that until stricter environmental protection and public health laws are passed and implemented by Colombia, CPF and related chemicals will continue to be imported from countries that have already banned them (Dowler, 2020). Colombian scientists should raise their voice to challenge blind acceptance of profits over unintended consequences, and efforts to prevent pesticide´s abuse should be encouraged.