Introduction

While Egypt was the cradle of monasticism since Antony, the stylite type of monasticism is rarely represented in the Coptic corpus of monastic literature. Agathon is one of few Egyptian monks to be a stylite on a pillar near Sakha. While the city is well attested in Coptic history, amazingly enough we do not find any traces about this saint.

In this paper, we will overview the history of the church in Sakha from the available sources, such as the book of the History of the Patriarchs or the Book of the Churches and Monasteries. then we will study the veneration of Agathon the Stylite in the liturgical calendars. We will study the liturgical texts relating to Agathon the Stylite with a brief commentary. Finally, we will make a short a conclusion.

Sakha. In the fourth century

The name of Sakha is a stronghold of Christianity. According to the martyrdoms of the great persecution in the fourth century, we know that there was a priest called Anua, priest of Sakha that the two brothers Piroou and Athom (Hyvernat, 1886-1887, p. 135-173) collected his relics of and deposited them in the church at Sunbat (Viaud, 1979, p. 26; Viaud, 1991, p. 1968a-1975b).

Balana (feast day: 8 Abib), a priest from Bara in Sakha district who sold his goods and distributed the proceeds to the poor. He professed his faith before the governor Arianus in Antinoopolis and was tortured and beheaded.

The seat of Sakha is mentioned in a letter written by Athanasius (Timm, 1992, pp. 2686-2694).

Agathon was contemporary to the great bishop Zacharias of Sakha (Müller, 1991, pp. 2368a- 2369a; Evelyn-White, 1932, pp. 276-280) and Agathon like him was disciple of the Abraham and George (Coquin, 1991, pp. 12a-13a) the disciples of John the Hegumen of Scetis (Zanetti, 1996, pp. 273-405) "the last great saints" (Evelyn-White, 1932. pp. 278-280).

Sakha in the book of the History of the patriarchs

In the sixth century

Severus of Antioch reposed in Sakha in the year 538 in the house of local notable called Dorotheus.1

In the seventh century

From Sakha at this time also came one of the compilers of the History of the Patriarchs, a monk named George (Jurja or Mirka) from the monastery of St. Macarius.2

During the patriarchate of Agathon the patriarch (661-677) (who is also contemporary to Agathon the Stylite) an incident showing the state of confusion between Chalcedonians and anti-Chalcedonians occurred in the city of Sakha, which was predominantly under the influence of a Chalcedonian majority. It had a magistrate, an archon by the name of Isaac, who, in conjunction with its Muslim governor, was able to prevail over the Chalcedonian majority. The viceroy of Egypt at the time was Maslamah ibn Makhlad ibn Samit al-Ansari (667-689). He sent seven bishops to Sakha to make an inquiry into the accusation that some officials had been branded. Together with Isaac, who was obviously a follower of Agathon the patriarch, the situation was clarified, and the accused were absolved. The life of Agathon the Stylite does not make any allusion to this event, which took place in his city.3

The patriarch Isaac (686-689AD) was a disciple of Zacharias the bishop of Sais, (Porcher, 1915, pp. 14-15) and before his ordination, there was another candidate called George from Sakha (Evetts, 1909, p. 276 [22]) which shows that Sakha maintained its reputation.

In the ninth -Tenth centuries

The prosperity of Sakha continued as this is apparent from the biography of the patriarch Cosmas (851- 858) who died while he was preparing a church in the diocese of Sakha (Abd al-Masih & Burmester, 1943, pp. 12 - 17, Translation: Labib, 1991, pp. 636b- 637b).

His successor Kha'il III, (880-907AD) (Labib, 1991, pp. 1412b-1413a). When he went to consecrate the church of Ptolomy at Sakha, when the bishop of Sakha was absent, the patriarch offered the liturgy which made the bishop angry and the dared to throw the oblation. By the end, the patriarch excommunicated the bishop and ordained another one (Abd al-Masih & Burmester, 1948, p. 70, (text) pp.103-104.).

In the Eleventh century

The bishop of Sakha, John known as Ibn al-Zalim, the scribe before his episcopate led a group of bishops and a body of the priests of Alexandria to go to Cairo and they made agreement to depose the father Christodoulus from the patriarchate as John the bishop of Sakha had quarrel with the patriarch. This plot was unsuccessful (Abd al-Masih & Burmester, 1959, pp. 172-173 (text), pp. 260-262 (translation)). This bishop John of Sakha was also among the delegation that chose Cyril II (Labib, 1991, pp. 675b-677a) the successor of Christodoulus (Abd al-Masih & Burmester, 1959, p. 207 (text), p. 321 (translation)).

In the book of the churches and Monasteries Twelfth century

According to the book of the churches and Monasteries ascribed to Abü al Makarim4 mentions about the church of al Mahallah al-Kubra, that was renovated in the reign of Senutiu who is Shenüde the 65th from the number of the Patriarchs and the bishop Anba Maqarah the bishop of Sakha in the year 754 of the Martyrs (1038AD) (Al-Suriani, 1984, fol.b-33a). While talking about Sakha, he highlights that it has a church named after the Virgin Mary where Severus of Antioch used to dwell in it, and another church named after the Archangel Michael, a third one dedicate to saint Cyr and two churches named after George and finally a church in Difraya near Sakha named after the Virgin and known also for the many miracles that took place in it (Al-Suriani, 1984, fol. 34a-b).

The same author narrates the conflict between the bishop of Sakha and the Patriarch Kha'il III the 46th (744-767) (Labib, 1991, p. 1410b-1412a) and how he excommunicated that bishop.5 Finally Abü al-Makarim states that according to the history of the Patriarchs that the biography of Theodosius the patriarch the 33rd that Dorotheus from Sakha restored and built monasteries and keeps instead of what were destroyed by the impious king Justinian and his companions (Al-Suriani, 1984, fol. 73b).

Conclusion

Despite the abundant data that we possess about the city of Sakha, nothing is mentioned about Agathon the Stylite which means that from the seventh to the twelfth centuries, there was no veneration for Agathon.

The Calendars

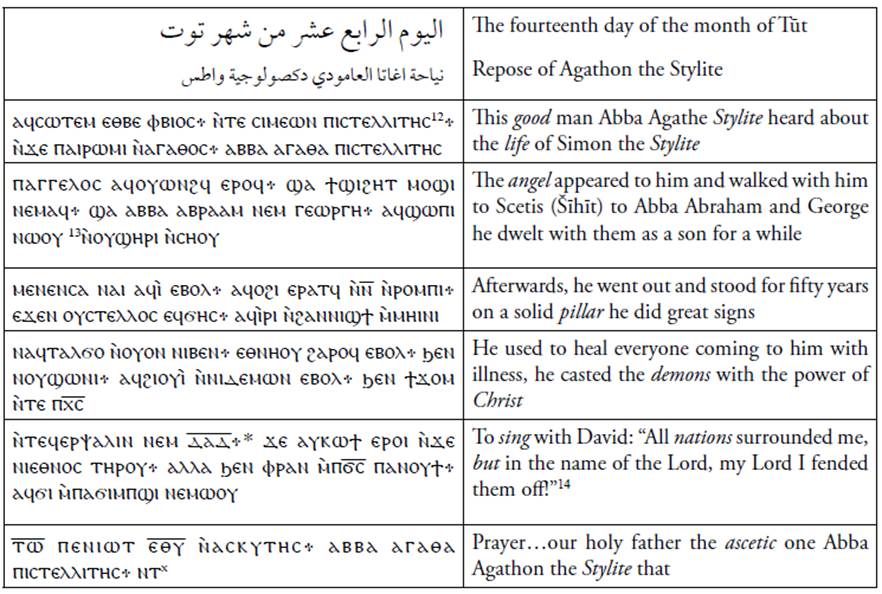

The Synaxarion on the 14 Tüt (Forget, 1905, p. 76 ; Basset, 1904, p. 364[150]) commemorates:

The Departure of St. Agathon the Stylite

On this day St. Agathon the Stylite, departed. He was from the city of Tannïs. The name of his father was Matra and his mother's name was Mariam. They were righteous and feared God. They loved to give alms and be merciful to the poor and needy. The thought of monasticism was always on his mind. When he was 35 years old, he was ordained priest, and he devoted himself to serve the holy church. He asked the Lord Christ by day and night to facilitate for him the parting from this world to go to the desert. The Lord Christ answered his request, and he went out from the city and came to Ternot (Mareot) and from there went to the desert. The angel of God appeared to him in the form of a monk who journeyed with him and brought him to the monastery of St. Macarius in Scetis. He came to the holy old men Abba Abraham and Abba George, became their disciple, and remained with them for three years. Then, they took him before the altar and in the presence of the Hegumen Abba John and for three days they prayed over the monastic garb. They then ordained him a monk and dressed him with the holy Scheme. From that hour he exerted himself with many worships, in continuous fasting and prayer and fought a great fight. He slept on the ground until his skin cleaved to his bones. He read continually the biography of Abba Simon the Stylite, and he thought of leading a solitary life. He took counsel with the holy fathers concerning that, and they approved his wish and they prayed for him. He left and came near the city of Sakha, province of Gharbia, where he dwelt in a small church. The believers built a place for him on a pillar, and he went up on it. During his days, a man appeared in whom dwelt an obstinate devil, who led many people astray. He sat in the middle of the church surrounded by people listing to him, carrying tree branches. Abba Agathon sent for the possessed and had him brought to him. He prayed over him and cast out the devil who led the people astray. Similarly, a woman claimed that St. Mina conversed with her and she commanded the people of her city to dig a well in the name of St. Mina to heal everyone who bathed in it. St. Agathon prayed down of martyrdom in the kingdom of the heavens. May his prayers be with us over that woman until he cast out from her that unclean spirit and he commanded the people to fill up that well with earth. At the hands of this holy man, St. Agathon, God worked many miracles, of healing sick people and casting out devils. The devils appeared to him in the form of angels, singing sweet songs and imparting blessings unto him, but by the might of the Lord Christ he knew their guile, he made the sign of the Cross over them, and they fled away defeated. When God wished to repose him from the labours of this world, he fell sick for a short while and delivered up his soul into the hand of God. The people who had benefitted from his sermons and teachings gathered around him and wept bitterly. This holy father lived for 100 years, of which he spent 40 years in the world and 10 years in the desert and 50 years in solitude upon that pillar. His prayers guard us against all our enemies, and Glory be to our God, forever. Amen.

Only one manuscript of the Menologus of the Gospels (14 Tūt) mentions Agathon the stylite6 and in the calendar of Abu Barakat Ibn Kabar (14 Tüt) we find the name of Agathon as saint, (not stylite) (Tisserant, 1913, p 254 [10])7 in the calendar of Qalqašandī: feast of Simeon the recluse (Coquin, 1975, pp. 375-411 especially p. 389), but he is not mentioned in the calendar of Ibn al-Rahib, as we find Isaac the recluse (Sidarus, 1975, Tafel 7). Amazingly enough, we find the Syriac calendar commemorates Agathon the stylite (7-8th century) on the 12th of September (Iylū.l) (Akhrass, 2015, p. 135). There are neither relics recorded,8 nor inscriptions mentioning his name (Papaconstatinou, 2001, p. 55).

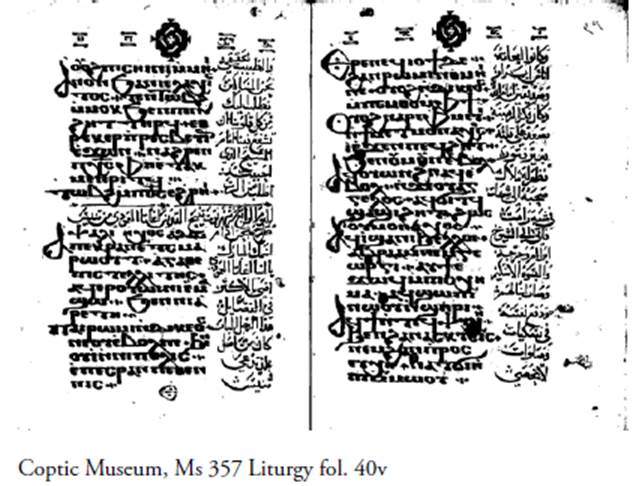

In the liturgical books

This saint is not mentioned in the manuscripts used by Bishop Samuel for his edition of the book the Order of the Church "Tartīb al-Bay'ah". This commemoration does not occur in the book of Turūhãt (Burmester, 1938, pp. 141-194 especially p.148). Yassa 'Abd al-Masih did not find any doxology in the seven manuscripts that he used for his article (Abd al-Masih, 1941, pp. 31-61 especially p. 38), the same could be said for the Ms Paris Copte 123, which is the book of doxologies for the first six months of the year. There is a group of monks who are called the stylites in the Coptic lectionary, this group includes Simeon the Stylite, Agathon, the Stylite, Luke, Barsuma, and Theodore disciple of Pachome, Pachome, Marcian, Simeon the young, Moses the black and Ephrem the Syrian (De Fenoyl, 1960, pp.51-53).

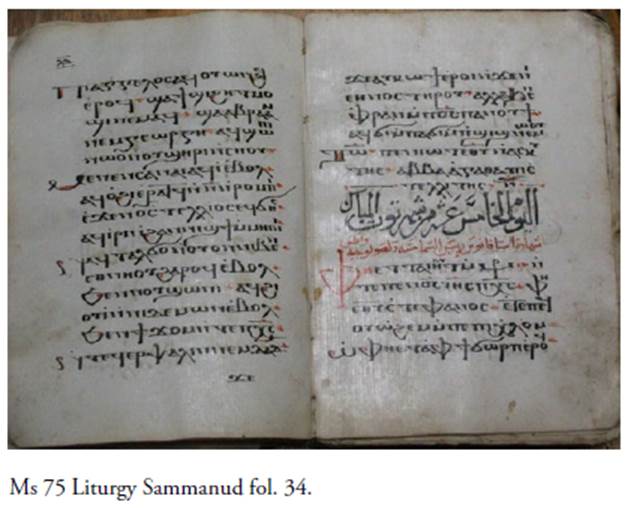

The Manuscript 75 Liturgy Sammanūd

The manuscript contains the doxologies and responses for the first three months i.e. Tūt, Babãh and Hatūr. The numbering is in Coptic Uncial on the verso. The text starts on ff.4 and the last part of the text 168 and the colophon is written by error as f. 199.

The colophon includes several important data; we will give the text in full.

The sponsor is the beloved son, the clever, intelligent, the established in his faith on the unshakable rock who gives alms to the poor and needy, the master (Mu'allim) Mišriqī Abū Kammūn, may the Lord God dwelling in the Highest Heaven reward his gifts forgiveness of his sins thirty, sixty and one hundred in the heavenly kingdom and will make his houses inhabited and protect his from the evil of the oppressors through the intercessions of the ever Virgin, the Angel, the martyrs and the saints. Amen

The scribe of this book the most humble of the priest, Yūhannã the scribe in Harit al-Rūm demands the fathers and brethren who read in this book to pray for the forgiveness and pardon and who says anything will get the same thirty, sixty and one hundred, thanks be to God.

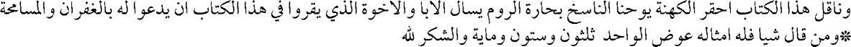

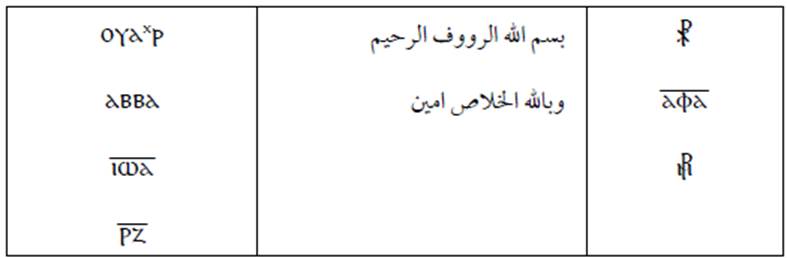

The archbishop Abba John the 107 in the time of the martyrs 1501 (= 1785AD)9

In the name of God the compassionate and merciful

The salvation is from God Amen

(This is) an inalienable endowment and eternal bequest for the church of the great saint Abanūb in the district of Sammanūd not to be sold or taken in pledge or taken out of his bequest for any reason of destruction. Whoever will take it out of his bequest will be condemned by Lord Christ condemnation without mercy and the patron saint of this church will be his adversary and whoever will keep it in its bequest will be absolved and blessed. May the sons of the obedience will get the blessing. Thanks be to God forever and who worked for that our honoured father Dawūd the monk the minister of this church, may Christ grant him his wage in the heavenly kingdom Amen!

The History of the Patriarchs is nearly silent (Khater & Burmester, 1970, p 294 (Translation), p. 169 (text)). The patriarch John XVIII started to establish the patriarchal library in Harit al-Rūm (Atiya, 1991, p. 1206b-1207b; Butler, 1887; pp. 278-284), unfortunately, we do not know the exact location of this library as the present edifices date from the time of Muhammad Ali. (Meinardus, 1977, p. 304-305; 1999, p.196).

The colophon highlights also that the minister of church of Sammanūd is a monk, however we do not know the name of his monastery. It is worth mentioning that the sponsor of this manuscript is a layman. The role of the notables increased especially in the eighteenth century.10

Commentary

The first quatrain, the text seems to be written in Arabic ⲁⲅⲁⲑⲁ as it should be the Greek vocative ⲁⲅⲁⲑⲉ

The text highlights the main reason that motivated him to become a Stylite is the reading of the life of Simon that was translated in Coptic and was published according to the manuscript 61 Vatican Library which dates to the tenth century (Cf. Chaîne, 1948). The quatrain states that an angel appeared to him and walked with him to Abba Abraham and George however the expression for a while  seems to be an Arabic idiom.

seems to be an Arabic idiom.

The fifth quatrain is taken from the doxology of Saint George, while in the doxology of Saint George is in the context, the use of this doxology is out of context. The text also mentions the duration of the saint on the pillar and the miracles The conclusion is the usual demand for the prayers of the saint. The doxology is another source of information of the life of Agathon the Stylite.

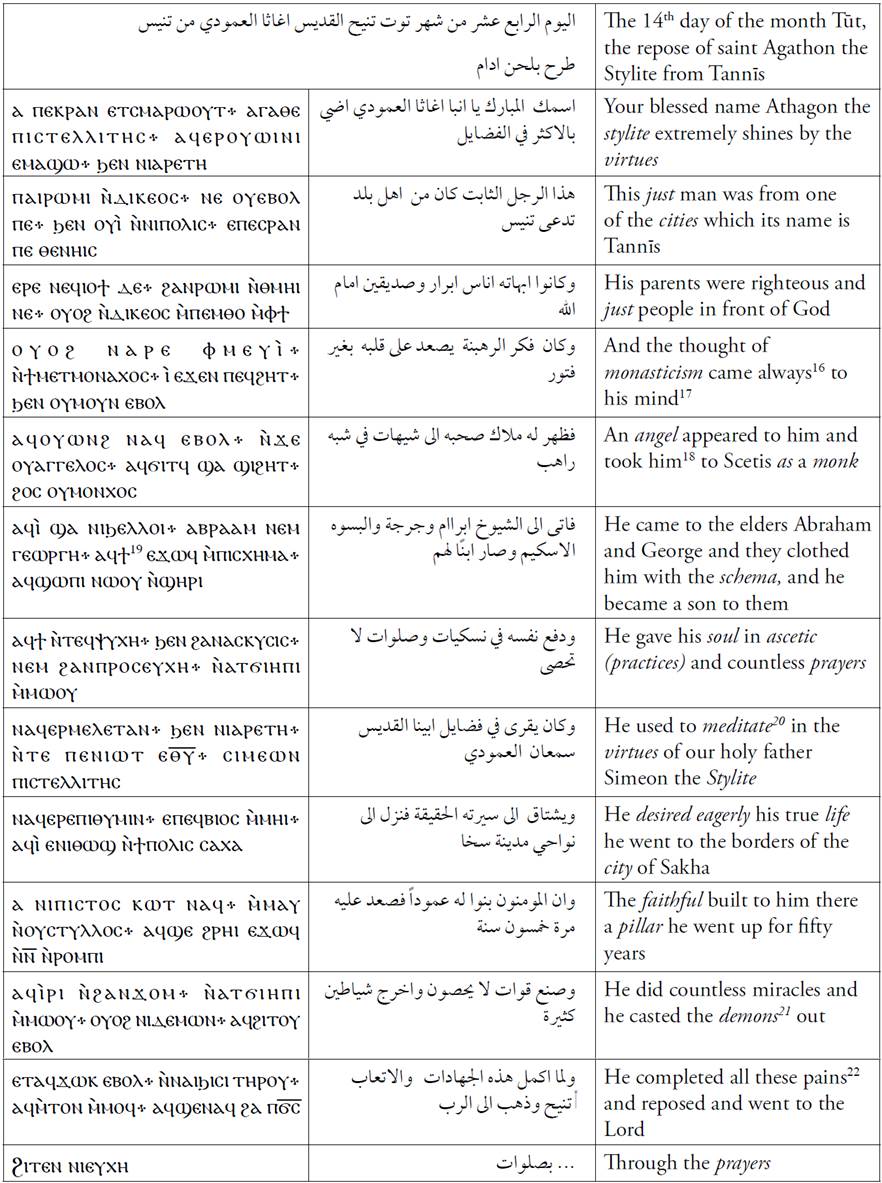

The Difnar14

This book was first compiled in the Upper-Egypt (Sahidic) (Krause, 2003, p 167-185; Cramer & Krause, 2008, p. 17-21) before the ninth century. The first manuscript that came to our knowledge in Lower-Egypt (Bohairic) dialect is from the monastery of Saint Antony as this is apparent from the colophon of the Manuscript of Saint Antony.

The month of the blessed month of Bābah is finished -with the help of our Lord Jesus Christ- to him is the glorification and praise for ever Amen- May his mercy be upon us Amen!

It was accomplished on the last day of Kīhak of the year 1101 of the pure martyrs (= 26 December 1384AD) in the monastery of Antony in the desert of Arabah. May our Lord Jesus Christ have mercy upon the sponsor, the owner, the reader and the poor scribe, through his prayers, Amen!

All the other existing copies -containing the full Coptic text- are mainly taken from this manuscript (Mekhaiel, 2010, p. 34-58).

Commentary

The quatrain is an introductory text praising the virtues of the saint. The second quatrain highlights the origin of the Saint from Tinnis (1992, p. 2686-2694). The following quatrain are parallel to the text of the Synaxarium. The names of Abraham and George are "the last great saints", of Scetis in the seventh century (Coquin, 1991, pp. 12a-13a; Evelyn-White, 1932, pp. 278-80). It is important to mention that this saint lived in Lower-Egypt around the sixth-seventh century which means that it was around the time of important events such as the usurper of Phocas, the Persian invasion, the Byzantine reconquest, and the Arabic conquest (Fraser, 1991, p. 183b-189b). However no mention of any of these events in biography of this saint. The city of Sakha it is worth mentioning that the spelling of the name of the city is not attested elsewhere (Timm, 1992, p. 2231-2237), it seems that it was taken from the Arabic text.

The text briefly mentions the miracles without giving details. Hence, we can say that the text of the Difnar here is relaying on the Synaxarion for the following reasons:

The spelling of the city Sakha is taken from Arabic.

The same could be said for the spelling of city Tannîs.

The biographical data are taken from the synaxarion without adding anything.

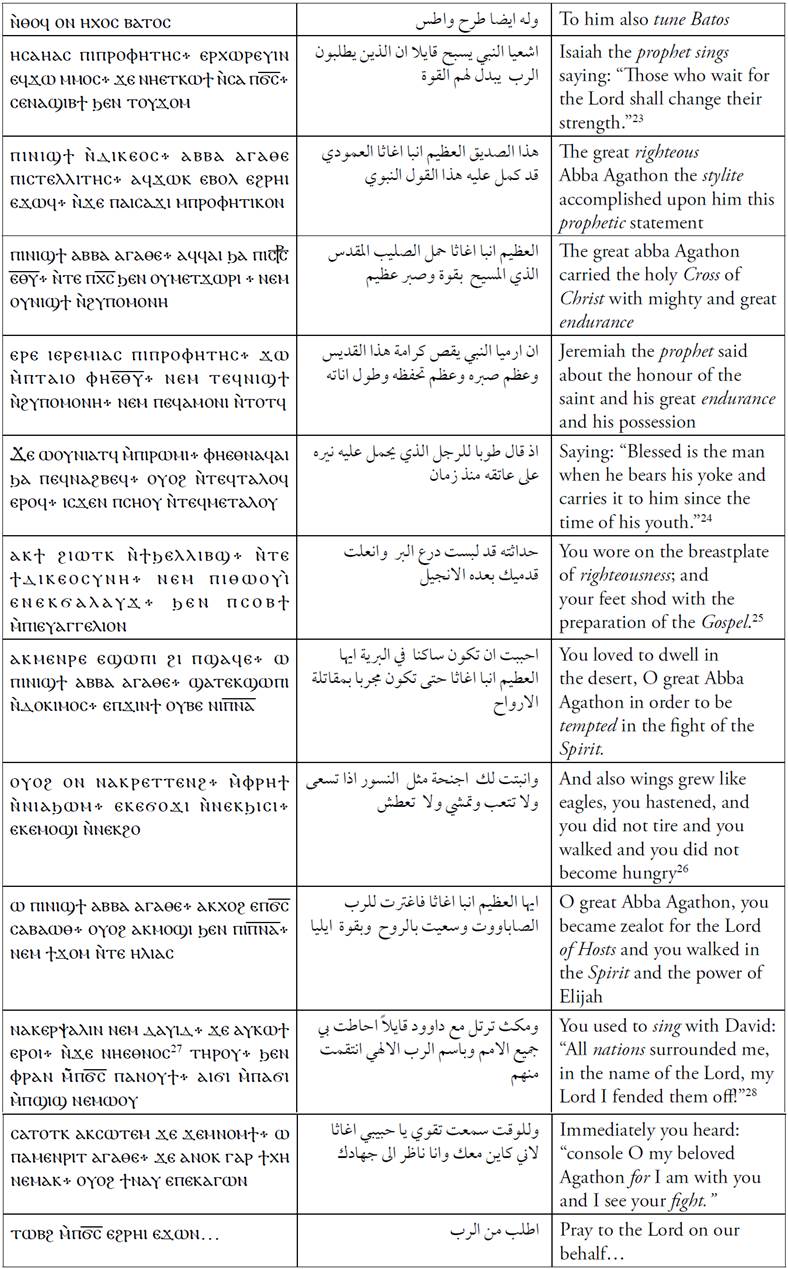

Commentary

The psali Batos does not provide biographical data about Agathon of Scetis. The author of this text has excellent knowledge of Scriptures mentioning verses from the Old and the New Testaments. The text could apply to any hermit or monk, we do not find any anthroponym or toponym. While the Psali Adam provides us with much information about his origin, his two masters Abraham and George in Scetis, his withdrawal to Sakha, etc.

Conclusion

In this article, we highlighted the importance of the city of Sakha (Stewart, 1991, p. 2087b-2088a), in the book of history of the Patriarchs, the book of the Churches and Monasteries (twelfth century). This saint lived in Lower-Egypt around the sixth-seventh century which means that he was contemporary to important events such as the usurper of Phocas, the Persian invasion, the Byzantine reconquest, and the Arabic conquest, but neither his biography nor the liturgical texts reflect any hints of these events. We found two sets of the liturgical texts are additional sources of information to our knowledge about Agathon the Stylite. A doxology Batos rarely attested in many manuscripts. Texts of the Antiphonarion (Difnar). These texts do not add much about the biographical data; however they show the interest and the veneration of this saint. Interestingly, while the pillar of Simeon the Stylite was remembered and venerated for long (Maraval, 1985, pp. 342-345) time, the pillar of Agathon is not mentioned anywhere, even his relics are not found. The church is considered as one of the places visited by the holy family.28