Introduction

International organizations have recognized that violence against women by their intimate partners is associated with structural inequality and have encouraged the international community to develop studies, programs, and policies to work toward its eradication (MEASURE-DHS, 2012; un, 1995; UNICEF, 2000; who, 2005). Some steps have been taken in that direction, for example, the National Center for Injury Prevention and Control, Division of Violence Prevention introduced a broader definition that shows that intimate partner violence is not limited to physical violence. It may include physical violence, sexual violence, stalking, and psychological aggression, at different levels of severity (Breiding, Basile, Smith, Black, and Mahendra, 2015). It has also been recognized as a worldwide public health problem (Caceres, Vanoss and Hudes, 2000; Ellsberg, Pena, Herradura, Lil jestrand, and Winkvist, 2000; Fischbach and Herbert, 1997; García and de Oliveira, 2011; Koenig et al., 2004; Parish, 2004; who, 2004), prevalent throughout the life course (Shackelford et al., 2003; Smith, Thornton, DeVellis, Earp, and Coker, 2002) and causing lifetime consequences (Fang and Corso, 2008; Foran and O'Leary, 2007; L. Heise, Ellsberg, and Gottmoeller, 2002; L. Heise and Garcia-Moreno, 2002; Jewkes, 2002; Krug, Mercy, Dahlberg, and Zwi, 2002; Ruiz-Pérez et al., 2013; White, McMullin, Swartout, Sechrist, and Gollehon, 2008).

A cultural explanation emphasizes the importance of cultural beliefs in violence production, particularly in the patriarchal family (Hagan, 1988), in the legitimacy of male control of women, for example over their sexual behavior (Graham-Kevan and Archer, 2008; Mayorga, 2012; Simmons, Lehmann, and Collier-Tenison, 2008), and in the influence of structural socioeconomic factors such as education and poverty (Krantz and Nguyen, 2009). Violence against women is explained not only by the action of individuals but also by the action or inaction of institutions (Barak, 2003; Franklin and Menaker, 2014). It is through the family institution first, and in society at large, that individuals learn the "expected" gender distribution of power. Power distribution in the family depends on family structure, and that structure reproduces gender roles and gender expectations. As power-control theory states, family structure varies within two extremes: the ideal-patriarchal and the ideal-egalitarian. The female-headed household is somewhere in between (Hagan, 1988; Hagan, Simpson, and Gillis, 1987).

In egalitarian families, control is equally distributed, and wives and daughters hold power and autonomy equal to that of male partners and sons; intimate partner violence is unlikely in this type of family (Jewkes, 2002). In patriarchal homes, on the other hand, there is an unequal distribution of power by gender; male partners have more power than female partners, and sons more power and freedom to make their own decisions than daughters. Parents are instrumental in enforcing this inequality through the way boys and girls are socialized (Hagan, 1988). The occurrence of intimate partner violence is more likely in the patriarchal family (Flake and Forste, 2006). In this type of family, gender roles are shaped and social status expectations are learned. Male children are encouraged to be autonomous, dominant, and controlling and are expected to hold positions of power at all levels of society. Female children are expected to be understanding, obedient, and submissive. Parents control their female children by controlling their behavior in order to "protect" them from danger (Hagan, 1988). This unequal distribution of power is mirrored later in adulthood between heterosexual intimate partners. Men usually control the family resources (Anderson, 1997; Dobash, Dobash, Wilson, and Daly, 1992) and make broader financial decisions, such as those involving investments, while women make decisions about the household budget (Jewkes, 2002), childcare, and childrearing (Alcantara, 1994; David, 1994). Men may also make decisions about family planning in an attempt to gain control over their female partners' sexual behavior.

However, violence against women may be explained not only by cultural beliefs in men's superiority, but also by male's feelings that their social status is lower than or inconsistent with the socially expected status for their gender (Atkinson, Greenstein, and Lang, 2005). The status inconsistency theory argues that men aligned with the principles of patriarchy understand power as a signal of masculinity and will turn violent when that power is challenged by their female partners (Atkinson, Greenstein, and Lang, 2005; Chung, Tucker, and Takeuchi, 2008). For example, research in developing-mostly patriarchal-countries has found that women who work and make higher incomes than their male partners (Chung, Tucker, and Takeuchi, 2008) or are socially active may be abused by them (Antai, 2011; David, Chin, and Herradura, 1998; Flake and Forste, 2006; Gage and Hutchinson, 2006; Heaton and Forste, 2007; Hindin, Kishor, and Ansar, 2008; Mann and Takyi, 2009; Meekers, Pallin, and Hutchinson, 2013).

Purpose of the Current Study

For decades, intimate partner violence and gender inequality have been systematically studied in developed countries. However, literature about Latin American countries, such as Bolivia, is almost nonexistent. Intimate partner violence against women is of particular concern in Bolivia, a country ranked second among ten Latin American countries in the prevalence of physical and sexual violence toward women (Hindin, Kishor, and Ansara, 2008). This study addresses this shortcoming. Using data gathered in Bolivia by MEASURE DHS (Demographic and Health Survey) in 2008, this study uses factor analysis and structural equation modeling, on a sample of2,759 Bolivian heterosexual couples, to analyze the correlation between the type of decision making at home and two categories of intimate partner violence: physical violence and psychological aggression. I analyze intimate partner violence -offending and victimization- as a consequence of three types of decision making at home-(1) patriarchal (equivalent to Hagan's ideal-patriarchal, when men made decisions alone), (2) egalitarian (equivalent to Hagan's egalitarian, when both the female and male partners made decisions together), and (3) matriarchal (the female partner made decisions alone, which is equivalent to female-headed households, described as being at a transitional stage in Hagan's classification). Since the World Bank (2016) shows that 32 % of Bolivians live in rural areas and 15,8 % live below the $3.10 PPP (purchasing power parity) a day, I also analyzed the impact of socio-economic variables, such as educational attainment, wealth, and place of residency.

My study was guided by three initial hypotheses: (1) intimate partner violence is correlated with the patriarchal-type family structure and less likely to occur in the egalitarian-type family; (2) that correlation follows the assumptions of the power-control and status inconsistency theories; women are abused by their male partners based on both male partners' beliefs in male superiority as well as the male partners' feeling that their social status is challenged by their female partners' power to make decisions at home; and (3) that these correlations will be moderated by education, wealth, and location (rural/urban) of residency.

Method

Participants

Indigenous peoples make up a high proportion of Bolivia's population. There are 104 indigenous groups (Lidchi, 2002), most of whom live in rural areas and are poor (Gigler, 2009). According to the GINI Index, Bolivia has the second highest level of income inequality in South America. In 2002, nearly 74 % of Bolivian indigenous peoples lived below the poverty line. In addition, a comparison between indigenous and nonindigenous peoples revealed that while, on average, indigenous peoples complete 6.5 years of school (females complete only 5.5 years), nonindigenous peoples complete nearly 10 years of school. Indigenous peoples are also shown to have higher levels of illiteracy: over 40 %. For females, however, illiteracy is nearly 60 % (Gigler, 2009; Heenan and Lamontagne, 2002).

This study uses the MEASURE DHS subsample of 2,759 heterosexual couples who had reported being married or living together at the time of the survey. The sample is representative of the Bolivian population, for example, regarding urban/rural distribution and ethnicity-57 % of the couples were living in urban areas and 43 % in rural areas, and 43 % identified themselves as nonindigenous while 57 % identified as indigenous - 30 % Quechua, 20 % Aymara, 3 % Guarani, and 4 % other-. The distribution by region was Chuquisaca (10 %), La Paz (19 %), Cochabamba (12 %), Oruro (9 %), Potosí (11 %), Tarija (10 %), Santa Cruz (18 %), Beni (7 %), and Pando (5 %). With regard to the education of female partners, 6 % had no education, 52 % completed elementary education, 28 % completed high school, and 14 % reached higher education. For male partners, 1 % had no education, 44 % completed elementary education, 35 % completed high school, and 20 % reached higher education. Forty-two percent of these couples were poor, 20 % were middle class, and 38 % were rich. In addition, the male partner was identified as the head of the household in 97 % of the households. In 72 % of households, the couples made decisions together, while household decisions were made alone by 11 % of female partners and 17 % of male partners.

Regarding intimate partner violence, both men and women had reportedly been victims. Female respondents reported that their partners: accused them of being unfaithful (20 %), acted jealous when the female partner talked with another man (25 %), humiliated or insulted them (26 %), threatened to abandon them (15 %), and threatened to take their children away (11 %). The figures reported for males in the converse situation were 25 %, 27 %, 13 %, 11 %, and 7 %, respectively. Female respondents reported that their partners pushed them (22 %), beat them (18 %), beat them with an object (5 %). The respective figures for male respondents were 12 %, 9 %, and 3 %.

Procedure

This study uses the data gathered by MEASURE DHS (hereafter identified as DHS), a United Nations program designed to provide technical and financial assistance to monitor public health in developing countries like Bolivia (Coa and Ochoa, 2009). In coordination with the Bolivian Ministry of Health and the Encuesta Nacional de Demografía y Salud (ENDSA), the Bolivian population has been surveyed every five years since 1984. For the 2008 survey, ENDSA used three questionnaires: one for the household, one for the women, and one for the men. Any available adult 18 years or older could answer the household questionnaire, and any qualified man and/or woman available at the time of the visit could answer the corresponding (man/woman) questionnaire. The questionnaires were administered in Spanish, the official language of Bolivia.

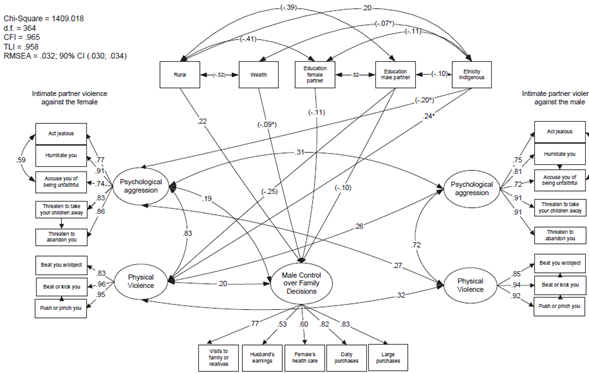

To conduct the analysis, I selected the variables pertaining to my interest based on two scales: the Conflict Tactics Scale (CTS) developed by Murray Straus in the 1970s (Straus, 2007) to measure physical and psychological abuses between intimates and the Decision Making scale designed by measure DHS to measure female autonomy (Coa and Ochoa, 2009). Then I ran a series of the nonlinear version of the Mplus exploratory factor analysis (EFA), exploratory structural equation modeling (ESEM), and structural equation modeling (SEM) procedures using the weighted least square mean variance (WLSMV) estimator for categorical indicators (B. Muthen, 1983; B. Muthen, 1984; L. Muthen and Muthen, 2009). Next, based on the answers to the decision-making questions, three dichotomous variables were created and three models of decision making at home were analyzed: first, when the male partner made decisions alone, second, when the female partner made decisions alone, and third, when both male and female partners made decisions together (table 1, shows the factors loading for the three models, and figure 1 shows the results for the first model: patriarchal decision-making).

Table 1 Factor loadings for the three models

Source: own elaboration.

N=2,749

Notes

1. The Conflict Tactics Scale (CTS) was used to measure psychological aggression and physical violence toward one's partner.

2. This Decision-Making Scale was developed by MEASURE DHS (see Demographic and Health Survey).

3. The estimates of goodness-of-fit for the three models are excellent according to three indicators: Comparative Fit Index (CFI), the Tucker-Lewis Index (TLI), and Root Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA).

a. Wife [made decision alone], Chi-square= 1339.762, df= 364, p-value=0.0000; CFI= .968; TLI= .961; RMSEA=.031 [C.I. .029 and .033].

b. Husband [made decisions alone], Chi-square= 1409.018, df= 364; p-value=0.0000; CFI= .965; TLI= .958; RMSEA=.032 [C.I. .030 and .034].

c. Together [wife and husband made decisions] = Chi-square= 1438.667, df= 364; p-value=0.0000; CFI= .965; TLI= .958; RMSEA=.033 [C.I. .031 and .034].

1. The Conflict Tactics Scale was used to measure psychological aggression and physical violence between intimate partners. 2. The Decision Making Scale developed by measure dhs was used to measure male control over family decisions. 3. All coefficients are standardized and significant at p<.0000 or at *p<0.005 levels. The inverse correlation between indigenous identity (ethnicity) and psychological aggression toward the female partner mus be studied further, since it could be explained by cultural differences between indigenous and nonindigenous populations regarding, for example, gender roles, gender expectations, masculinity/feminity. Source: own elaboration.

Figure 1 Structural model for intimate partner violence and patriarchal decision-making at home in a Bolivia sample

Measures

Throughout this study, physical violence is defined as "the intentional use of physical force with the potential for causing death, disability, injury, or harm"; and psychological aggression is defined as "the use of verbal and non-verbal communication with the intent to a) harm another person mentally or emotionally, and/or b) exert control over another person" (Breiding, Basile, Smith, Black, and Mahendra, 2015, p. 15). Decision making refers not only to decisions about money but also to the ability to negotiate one's preferences in regard to everyday decisions, such as whether to visit family or relatives. The wealth index designed by MEASURE DHS measures the socioeconomic status of the household. It is calculated based on country-specific household assets and utilities such as water, electricity, telephone availability, and sewer systems. It also includes appliances, computers, internet access, type of dwelling, dwelling ownership, and waste disposal (Rutstein and Kiersten, 2004).

The most parsimonious versions of the scales developed by MEASURE DHS were used to measure the following dimensions.

Physical violence

To measure this dimension, three dichotomous (Y/N) items were included: During the last 12 months, did your partner (1) push or pinch you, (2) beat or kick you, and (3) beat you with an object?

Psychological aggression

Five dichotomous (Y/N) items were included: During the last 12 months did your partner (1) accuse you of being unfaithful, (2) act jealous when you talked with another man/woman, (3) humiliate or insult you, (4) threaten to abandon you, and (5) threaten to take your children away?

Decision making at home

Respondents were asked who had the final word regarding (1) the female's healthcare, (2) large purchases, (3) daily household purchases, (4) visits to family or relatives, and (5) how to spend the male partner's earnings. Three possible answers were analyzed, i.e., (1) the female partner alone, (2) the male partner alone, and (3) the female and the male partner together.

Observed variables

The females' and the males' education

These factors were measured with a single item: highest educational level. The variable was codified as follows: 0 = No education, 1 = Elementary, 2 = Complete or incomplete high school, and 3 = Higher education.

Location of residency (urban/rural)

This variable was measured with a single item (1 = urban, 2 = rural) that was taken directly from the address of the household.

Ethnicity

This variable was measured with a single item (1=nonindigenous; 2= indigenous-Aymara, Quechua, Guarani, and other).

Factor analysis

Three structural models were used to measure the correlation between two categories of intimate partner violence (i.e., physical violence and psychological aggression) and the type of decision making at home: (1) egalitarian -the female and her male partner made decisions together-; (2) patriarchal/male head of household -the male partner made decisions alone-; and (3) matriarchal, female head of household -the female partner made decisions alone- (see table 1). Each model included five latent constructs -physical violence and psychological aggression against both the male and the female partners and the type of decision making- and five observed variables: location of the residence, education of the female partner, education of the male partner, ethnicity, and wealth. The sample size and the magnitude of the factor loadings show that all the scales are reliable (Guadagnoli and Wayne, 1988; Sharma, 2000). The most parsimonious resulting models fit the data well, as shown by three indicators: The Tucker-Lewis Index (TLI), the Comparative Fit Index (CFI), and the Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA). For the first two, values greater than .95 indicate that the models fit the data well. The last one provides information on how well the model fits the data into a confidence interval; values of.05 and lower indicate an excellent fit (Byrne, 2010). The signs of the parameters were also found in the expected direction, and the correlations were highly significant (p < 0.000).

Results

The Bolivian population was predominantly patriarchal (Heaton and Forste, 2007; Lidchi, 2002), a large percentage lived in rural areas, and many were poor. Physical violence was commonly used by these Bolivian respondents and their families. For instance, 65 % of females and 78 % of males reported being beaten by their parents during childhood, and 38 % females and 45 % of males witnessed their mothers being beaten by their fathers or stepfathers. Even though intimate partner violence decreased in the respondents' generation, it was prevalent: 18 % of female and 9 % of male respondents reported being beaten or kicked by their intimate partners, and 5 % of female and 3 % of male respondents were beaten with an object. In addition, of those who were physically attacked by their partners, 76 % of females and 57 % of males used violence to defend themselves from the attack.

Similarities between the three types of decision making

Regardless of who makes the decisions at home, this study found the following correlations: Psychological and physical victimization were correlated for both females (.83) and male partners (.72), which suggests a co-occurrence of different types of victimization. Psychological victimization of the male partner was correlated with physical violence (.26) and psychological aggression (.31) against his female partner. There was a correlation between the male's physical victimization and the female's psychological (.27) and physical (.32) victimization. Acting jealous and accusing one's partner of being unfaithful were correlated for the female partner (.59) and the male partner (.63) (see figure 1).

Intimate partner violence and the egalitarian family

The results of the model indicated an excellent fit: Chi-square = 1438.667, p < 0.000, df = 364; CFI = .965; TLI = .958; RMSEA = .033, CI [.031, .034]. Egalitarian decision making was inversely correlated with the female partner's psychological (-.25) and physical (-.21) victimization as well as with the male partner's psychological (-.15) victimization. Living in rural areas was correlated with egalitarian decision making (.18) but was inversely correlated with wealth (-.52); female's education (-.42), and male's education (-.40). Indigenous identity was correlated with rural areas (.19) and inversely correlated with women's education (-.11) and men's education (-.10). At the less significant level of p<0.005, indigenous identity was correlated with the female partner's physical victimization (.24).

Intimate partner violence and the patriarchal family

The results of the model indicated an excellent fit: Chi-square = 1409.018, p < 0.000, df = 364; CFI = .965; TLI = .958; RMSEA= .032, CI [.030 and .034]. Contrasting with the egalitarian family, the patriarchal-decision-making-type family was directly correlated with the female partner's psychological (.19) and physical (.20) victimization. It was not correlated with violence against the male partner by the female partner. In rural areas, it was likely that the male partner alone made decisions (.22). This type of decision making was inversely correlated with the female partner's education (-.11). The male partner's education was also inversely correlated with the female partner's physical (-.25) victimization and with his patriarchal decision making (-.10). Indigenous identity was correlated with rural areas (.20) but inversely correlated with the female partner's education (-.11) and the male partner's education (-.10). At the less significant level of p<0.005, indigenous identity was correlated with physical violence against the female partner (.24) and contrary to the nonindigenous, it was inversely correlated with the female partner's psychological aggression (-.20) (see figure 1).

Intimate partner violence and the matriarchal family

The results of the model indicated an excellent fit: Chi-square = 1339.762, p < 0.000, df = 364; CFI = .968; TLI= .961; RMSEA = .031, CI [.029 and .033]. Contrasting with the egalitarian family, the matriarchal decision-making-type-family in which the female partner alone made decisions was directly correlated with her psychological (.17) and physical (.11) victimization as well as with her male partner's psychological (.14) victimization. The male's psychological victimization was directly correlated with his patriarchal decision making (.14), and the female partner's psychological (.31) and physical (.27) victimization. In rural areas, it was unlikely that the female partner alone made decisions (-.39); however, this type of decision making was directly correlated with wealth (.13), the female's education (.12), and the male partner's education (.10). At the less significant level of p<0.005, the male partner's education was inversely correlated with his female partner's physical victimization (-.26).

Discussion and Policy Implications

The findings of this study support my hypotheses and the arguments that gender inequality and violence against women may be explained by socio-economic inequalities (Barak, 2003, 2006) and institutionalized norms imbedded in sociocultural beliefs (Hagan, 1988). The Bolivian population is majority patriarchal (Heaton and Forste, 2007; Lidchi, 2002) and highly unequal by gender: 31 % of girls between 10 and 18 years old do not attend school and one in three female Bolivians is illiterate (UN-Women, 2018). Inequality is also highly dependent upon place of residency: 90 % of the rural population is poor; the literacy gap between men and women is as high as 10,8 % in rural areas (3,1 % in urban) (ONU-Mujeres, 2016; un-Women, 2018); 41 % of the rural population speaks Castellano/Spanish , 20 % speak Aymara, and 35 % speak Quechua, compared to 82 %, 7 %, and 18 %, respectively, of the urban population. Being less than fluent in the Spanish language may put the rural and indigenous Bolivian population at a disadvantage since it may limit people's access to services and the understanding of their human and socio-economic rights.

Moreover, these findings demonstrate that gender distribution of power may cause conflict between intimate heterosexual partners (Anderson, 1997; Dobash, Dobash, Wilson, and Daly, 1992; Jewkes, 2002), and that such distribution could lead to egalitarian, matriarchal, or patriarchal decision making at home and, that there are differential consequences for both intimate partner offending and victimization. Wealth and higher socioeconomic status are associated with equality between men and women (Krantz and Nguyen, 2009), and equality in decision making is correlated with less violence. However, women who have more resources and power than their male partners may still be abused by them (e.g., David, Chin, and Herradura, 1998). This apparent contradiction may be explained by the status inconsistency theory: Men become abusive if their assumed dominant status is threatened by their female partners (Dobash, Dobash, Wilson, and Daly, 1992; Gelles, 1974; Mann and Takyi, 2009). In addition, these results suggest cultural differences, by ethnicity, regarding psychological aggression toward the female partner. The inverse relationship between patriarchal decision making and indigenous identity, may be explained, for example, by the fact that individuals use different ways to spite the partner, which are culturally constructed. Finally, as this study demonstrates, there are gender differences in intimate partner violence.

With regards to policy implications, since intimate partner violence is correlated with the type of domestic decision-making, the Bolivian government should first develop and/or strengthen policies and programs to eradicate gender inequality. Those programs should focus on improving women's access to education, the job market, and entrepreneurial opportunities; for example, programs that support rural communities, such as Rural Partnerships Project (PAR), Community Investment in Rural Areas Project (PICAR), and Project for Agricultural Innovation and Services (PISA), founded by the World Bank (The-World-Bank, 2018), should be expanded by the Bolivian government to cover women from all socio-economic spectra and become a source of more sustainable and generalizable opportunity for women's empowerment. However, without support of other measures taken in conjunction, these programs have the potential to enhance the male perception of status inconsistency, so the Bolivian government also needs to lead a cultural shift designed at normalizing egalitarian family structures and highlighting the healthy consequences of shared decision making.

Finally, even though it is not the scope of this work, the study shows that regarding intimate partner violence, both males and females can be victims and offenders and, therefore, future research should analyze the forms in which men and women are socialized, as well as concepts such as masculinity and femininity, to establish patterns of behavior and potential cultural changes in topics such as gender roles and expectations among the Bolivian population.

Strengths, limitations and future research

This study has several strengths. First, the dataset facilitated the analysis of the answers for couples -males and females who were living together at the time of the interview-. Second, because a large percentage of Bolivia's population lives in rural areas, this dataset allowed me to make urban and rural comparisons. Third, this dataset also allowed me to analyze indigenous/nonindigenous differences. Fourth, this study is a step toward the measurement of women's empowerment that has been recognized as key to the eradication of violence against women.

However, five limitations must be considered. First, the questions regarding decision making were included only in the female's questionnaire; they were designed to measure female autonomy (Coa and Ochoa, 2009). Hence, future studies should be conducted with both male and female respondents to decision making questions. Second, this study contributes only to the understanding of heterosexual intimate relationships; future research should also consider including other forms of intimate relationships. Third, the analysis of indigenous and nonindigenous suggests that may be cultural differences between these two populations, for example, regarding physical violence and psychological aggression in the patriarchal family. Future research should explore differences and similarities regarding gender roles and gender expectations between the two groups. Fourth, since Bolivia is primarily a patriarchal country, this study contributes to the understanding of patriarchal societies but gives us less information on egalitarian societies. Future comparative studies of Latin American societies with diverse patterns of power distribution would prove fruitful. Finally, this study used a 2008 dataset and therefore further research should use more recent data to analyze possible changes over time as well as patterns regarding intimate partner violence and decision-making.

Conclusions

The findings of this study support the hypotheses that intimate partner violence is correlated with the type of domestic decision making, that the correlation follows the power-control and status inconsistency theories, and that these correlations are mediated by socioeconomic variables. The study shows that in households in which the distribution of power is egalitarian or evenly distributed between female and male partners, intimate partner violence is unlikely to occur. In rural areas, Bolivian women are more vulnerable, men more often make decisions alone, and women are less educated and poorer than in urban areas. In the patriarchal-type family, men make decisions and may abuse their female partners physically and psychologically. This type of family is poorer and less educated. Indeed, education seems to be key, since the male's education is inversely correlated with the female's physical victimization. In some wealthier, more educated households, the female partner makes decisions alone but can still be physically and psychologically abused by her intimate partner. This type of household is unlikely to be found in rural areas.

Finally, these findings also support Barak and his colleagues' argument that intimate partner violence is influenced by structural factors, such as patriarchal beliefs, social power structure, poverty, and social inequalities (Barak, 2003, 2006). Therefore, it is necessary to promote programs to eradicate violence against women, such as the one promoted by The United Nations Population Fund that targeted boys and men and challenges traditional concepts of masculinity (UNFPA, 2014) while providing training opportunities to combat poverty and marginalization.

Because of the uniqueness of the Bolivian population (e.g., high proportion of people living in rural areas, large percentage of indigenous population, highly patriarchal, and highly unequal), these findings must be tested in other populations, preferably through comparative analysis.