Introduction

Peru is one of the few countries in the world in which a variety of tuberculosis forms abound. In 25% of tuberculosis cases there is extrapulmonary involvement 1,2. The Peruvian Ministry of Health (MINSA) has an operational report from 2015 containing a total of 20,203 new cases of tuberculosis, among which 16,342 (80.8%) were pulmonary tuberculosis (PTB) and 3,861 (19.2%) were extrapulmonary tuberculosis (EPTB). Within the EPTB cases, males were predominant, with a higher number of cases between 15 and 44 years 3.

The extrapulmonary forms include central nervous system, peritoneal, lymph node, and osteoarticular forms, among others. However, there are very uncommon forms which are rarely seen or are not reported due to an unsuspected diagnosis 1,4,5.

Pharyngeal tuberculosis is an extrapulmonary manifestation of this disease which accounts for less than 1% of cases 6,7. There are few case reports of this type worldwide, and the nasal airway has been suggested as the principal means of transmission for the infection 8. There are no known case reports of this type in Peru.

We present the case of a 42-year-old patient who was seen due to chronic refractory pharyngitis. A series of exams were ordered, with a positive result for pharyngeal tuberculosis.

Case report

A 42-year-old male patient with no significant epidemiological or medical history, a native of Ica, was seen for a sore throat and pharyngeal lump. He reported having begun to experience a sore throat approximately two months before, and had been seen at the health center and treated for chronic pharyngitis with painkillers and antibiotics.

He continued to have discomfort, and began to notice a pharyngeal lump which made swallowing food difficult, associated with a 10 kg weight loss, and therefore was seen by an otorhinolaryngologist. On physical exam, a small, whitish lump on an erythematous base was seen on the left oropharynx (Figure 1).

Figure 1 Shows a small, whitish lump on an erythematous base on the left oropharynx (arrow) with periodic secretion, as described by the patient.

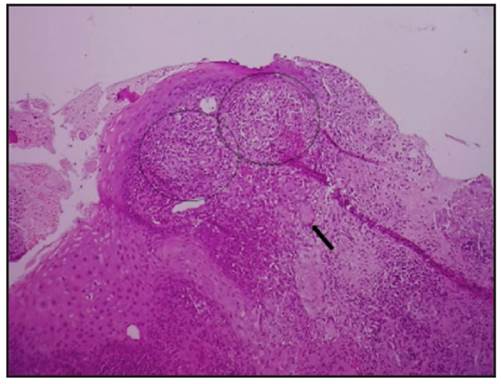

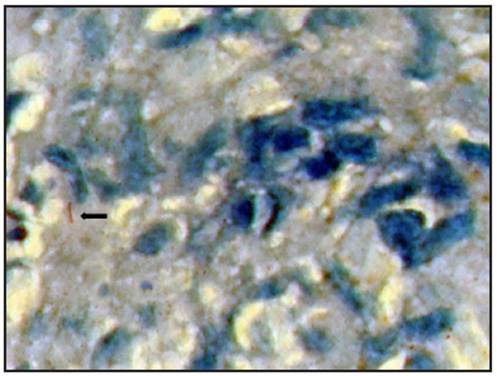

Laryngoscopy was ordered which did not show involvement of upper airways other than that previously described: a granulomatous lesion extending to the palate, from which a biopsy was taken. The sample was sent for analysis to rule out a specific chronic process. The biopsy results showed multiple granulomatous formations, some with central caseous necrosis and Langhans multinucleated giant cells (Figure 3). Furthermore, when the sample underwent Zielh Neelsen staining, it was positive for Koch bacilli (Figure 4), giving the correct histopathological picture for pharyngeal tuberculosis.

Figure 3 This sample shows multple granulomatous formations, some with central caseous necrosis (circles) and Langhans multinucleate giant cells (arrow). Staining method: hematoxylin-eosin. Magnification: 100x.

Figure 4 Exposure of the sample to Zielh Neelsen staining was positive, showing Koch bacilli, providing the correct histopathological picture for pharyngeal tuberculosis. Magnification: 1,000x. Staining method: Zielh-Neelson staining.

Tests were run seeking the primary focus, with disseminated bilateral miliary pulmonary lesions seen on the chest x-ray (Figure 2), confirming a form secondary to systemic tuberculosis. The patient was informed of the diagnosis and referred to pulmonology to begin treatment. Currently, the patient is receiving 2HREZ/4H3R3 medical treatment and is progressing well with no complications. We obtained the patient's informed consent to write this article.

Discussion

Globally, tuberculosis continues to be a public health problem. It is a preventable and curable infectious disease, which may attack any part of the body 9. In Peru, almost 27,000 new cases of active disease are reported per year, and we have one of the highest rates of tuberculosis among American countries, with it being the 15th cause of death, nationally 3. Ica is a very high-risk zone, with an incidence of 78/100,000 inhabitants per year.

Extrapulmonary tuberculosis is the new case in which tuberculosis is diagnosed in one or more organs other than the lung, using bacteriological, clinical, histological or other criteria 3. The preferred sites are the lymph nodes and pleura; on the other hand, in otorrhynolaryngology, the most common form of tuberculosis is that of the lymph nodes, followed by the larynx 10,11, with the pharyngeal form being very rare 6,12-14.

Pharyngeal tuberculosis has been described in few cases, with odynophagia being the main chief complaint 6. In most cases, it results from direct dissemination (through expectoration and inhalation of bacilli) or through the bloodstream. The first form was the case for our patient, as described in the literature 15. Bacilloscopy tends to be negative, with anatomical pathology being essential for diagnosis 6,12.

The recommended treatment regimen is the one used in our patient, as no resistance has been reported. An immediate diagnosis favors adequate resolution of the disease and prevents drug resistance 1,2,6.

text in

text in