Introduction

Bilateral peripheral facial paralysis, or facial diplegia (FD) is a rare neurological manifestation in which each facial nerve is affected simultaneously or within 30 days of each other, accounting for less than 2% of facial pa ralysis cases, with an estimated global incidence of one case per five million population. The most common cause is Guillain-Barré syndrome (GBS), or acute-onset poly-neuroradiculopathy 1, in which facial paralysis occurs in 24 to 60%, in most cases bilaterally. Isolated FD with no or slight involvement of the extremities, is an atypical and rare variant of GBS 2,3. Several types of infection have been associated with GBS, mainly respiratory and gastrointestinal in 70% of cases. The association with lep tospirosis, one of the most widely disseminated zoonoses worldwide (caused by a spirochete from the order Spirochaetales, family Leptospiraceae, and genus Leptospira), has been recorded less frequently 4-7. In most cases, this infection has a biphasic clinical presentation which begins with a septicemic phase, followed by immune signs with a broad clinical spectrum ranging from febrile syndrome with mild constitutional symptoms to severe disease with multiple organ failure 8. It is drawn to certain organs such as the liver, kidneys, heart and skeletal muscle, but also shows neurological signs in 12-40%, such as aseptic meningoencephalitis, cerebrovascular accidents, mono or polyneuritis, cranial nerve paralysis, inflammatory myelopathy, radiculopathy, and the previously mentioned GBS 9,10. The goal of this article is to describe the be havior of two unusual cases of patients with leptospirosis who developed bilateral facial paralysis in the course of their illnesses, as an atypical variant of GBS, given the diagnostic challenge for clinicians posed by this disease.

Clinical cases

Case 1

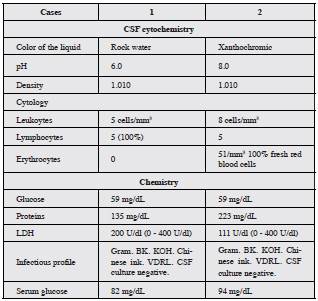

A 27-year-old male, with no relevant medical history, was seen in the emergency room due to a nine-day history of unquantified fevers, chills, headache, abdominal pain and myalgia, and subsequently developed right peripheral facial palsy, followed by contralateral involvement on the next day, associated with upper extremity paresthesias. On physical exam, he had normal vital signs, with no higher mental function problems, peripheral facial biparesis with out involvement of other cranial nerves, 5/5 strength in all extremities, normal myotendinous reflexes and bilateral flexor plantar reflexes. A simple tomography of the head on admission was reported to be within normal limits, the complete blood count showed leukocytosis (12,800 cells/mm3) without neutrophilia, kidney and liver function were normal, and serology for Leptospira was IgM positive and IgG negative. He was therefore diagnosed with leptospirosis, beginning treatment with 1 gram of intravenous ceftriaxone every 12 hours for seven days. Due to persistent neurological findings, simple magnetic resonance imaging of the brain, with contrast, was performed, which was normal, while the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) showed albuminocytological dissociation (Table 1, Case 1), suggesting the atypical facial diplegia variant of GBS. Electromyography and conduction velocity tests of each facial nerve supported the diagnosis, showing bilateral demyelinating neuropathy with signs of reinnervation. The patient underwent physical rehabilitation and speech therapy, with gradual recovery and no swallow ing or respiratory difficulties, or weakness in his extremities.

Case 2

A 36-year-old male international bus driver, with no relevant medical history, was seen in the emergency room due to five days of 38.8°C fever, chills, myalgias, arthralgias, generalized colicky abdominal pain of variable intensity and self-limited epistaxis. On physical exam, he had generalized mucocutaneous jaundice, mild dehydration, epigastric and right upper quadrant pain on palpation, with hepatosplenomegaly confirmed by a total abdominal ultrasound. Blood chemistries showed hemoconcentration (hemoglobin/hematocrit ratio = 42.7% / 12.6 g/dL = 3.38), thrombocytopenia (73,000/mm3), direct hyperbilirubinemia (total 5.2 mg/dL, direct 3.37 mg/dL), elevated transaminases (ALT 165 U/L, AST 150 U/L mg/dL), alkaline phosphatase (237 IU/I) and lactate dehydrogenase (1,098 IU/I), as well as microscopic eumorphic hematuria (10-15/field) with proteinuria (2+). A 24-hour follow up showed leukocytosis with neutrophilia (WBC 12,200 cells/mm3, 80% neutrophils), decreased plate lets (35,000 mm3), elevated CRP (44 mg/dL) and AKIN I acute kidney injury AKIN I (Cr 1.7 mg/dL). An infectious disease panel was ordered, which was negative (serology for Leptospira IgM and IgG, dengue, hepatitis A, B and C, HIV, syphilis, malaria and bacteremia). However, due to his signs and symptoms and paraclinical exams, a tentative diagnosis of Weil syndrome was made, beginning empirical treatment with 1 gram of intravenous ceftriaxone every 12 hours along with fluid resuscitation, and ordering a microscopic agglu tination test for Leptospira (MAT), which confirmed the diagnosis, yielding a positive result for serogroup Australis 1:200 and serogroup Cynopteri 1:400. On the tenth day after the onset of symptoms he developed left peripheral facial palsy with contralateral involvement 24 hours later (facial diplegia), with no other relevant findings on physical exam. A simple head tomography was normal, while the CSF showed albuminocytological dissociation (Table 1, Case 2), suggesting an FD variant of grade 1 Barré Hughes GBS, without progression of the neurological deficit, and thus immunoglobulin or plasmapheresis treatment was not begun. The patient was discharged with rehabilitation and glucocorticoids, as well as follow up with clinical neurology. The FD gradually resolved after three weeks of treatment.

Discussion

We present two cases of patients with leptospirosis in different clinical scenarios, the first with classical leptospi rosis and the second with Weil syndrome, who during the convalescent phase developed peripheral facial biparesis without extremity involvement, as a rare neurological complication of an atypical variant of GBS. This immune-mediated polyneuroradiculopathy is considered to be the most common cause of acute flaccid paralysis worldwide, after the eradication of poliomyelitis 11. Its most common forms are acute inflammatory demyelinating polyneuropathy (AIDP), acute motor axonal neuropathy (AMAN), and acute motor and sensory axonal neuropathy (AMSAN). However, there are atypical variants such as Miller Fisher syndrome (MFS), Bickerstaff encephalitis, the pharyngeal-cervical-brachial (PCB) variant, sixth cranial nerve palsy and FD, which make it difficult to recognize the disease and entail a diagnostic challenge 12. A prospective study of 250 pa tients with GBS found that MFS (5%) and the PCB variant (3%) are the most frequent subtypes, while isolated FD has been reported in 1% of patients 13.

Various viral (cytomegalovirus, Epstein-Barr, influenza A, enterovirus, Zika) and bacterial (Mycoplasma pneu moniae, Haemophilus influenzae, Campylobacter jejuni) infectious agents have been associated with the induction of both humoral and cellular immune responses to create IgG1 and IgG2 antibodies against the axons and myelin, due to molecular mimicry between the oligosaccharides of the infectious organisms and the gangliosides of the neuronal membrane (GM1-GD1a) 14. However, in leptospirosis, the pathophysiology of neurological involvement is still unknown. Some hypotheses propose the presence of immune mechanisms as an explanation for this disease's polymorphic clinical manifestations, including systemic vasculitides with activation of circulating immune complexes which develop 6-15 days after symptom onset 15,16. Another hypothesis is a cross reaction against the myelin sheath of the peripheral nerves 17 caused by globally distributed bacterial zoonoses. Human leptospirosis results from contact with water, soil or foods that have been contaminated with the urine of rats, dogs, pigs or other infected animals. Motile leptospires penetrate broken skin or mucous membranes and cause an acute and systemic illness characterized by a sudden onset of fever, myalgias, intense headaches and conjunctival hemorrhages. The clinical manifestations of the disease are not pathognomonic; therefore, leptospirosis has often been mistakenly diagnosed. Most human cases are mild and unjaundiced; however, 5 to 30% of jaundiced cases may be fatal, due to hemorrhagic complications, aseptic meningitis and kidney failure (Weil syndrome). Wallerian degeneration and perivascular and perineural inflammatory infiltrates de scribed on neuromuscular biopsies of leptospirosis patients validate the association of GBS as a complication of this spirochete infection 17,18.

An association with GBS was found in a literature re view of the last 20 years, in which only eight case reports were found of associated facial paralysis, including three bilateral forms of the disease with comparable neurologi cal involvement and duration to the cases described in this report 19-22. There is no available literature to date on leptospirosis cases associated with the atypical FD variant of GBS, possibly due to a lack of studies on this condition.

The diagnosis of GBS can be based on Wakerley et al.'s modified criteria, in which certain clinical characteristics, including the history of infectious symptoms, presence of bilateral facial weakness, distal paresthesias, decreased or absent deep tendon reflexes and a monophonic disease course with a 12-hour to four-week interval between the onset of the neurological deficit and its nadir, strongly sug gest the FD variant of GBS 23.

There are currently no serum, urine or CSF markers to confirm the disease. However, albuminocytological disso ciation (a normal cell count with elevated proteins) in the CSF is a finding which points to a GBS diagnosis 24. In a study of CSF samples from 474 patients with GBS, the sensitivity of albuminocytological dissociation was found to depend on the time at which the sample was taken, being positive in 49% on the first day of the disease and increas ing to up to 88% after the second week 25. Pleiocytosis (more than five leukocytes in the CSF) is unusual in GBS, but approximately 15% of patients may have a leukocyte count ranging from 5 to 50 cells per high power field, as seen in the second case presented 26.

Conclusion

Leptospirosis is a reemergent zoonosis in the world, and the second cause of febrile syndrome in Colombia. Although kidney, liver and lung involvement are more frequent, neurological complications may develop. Therefore, if facial diplegia develops, the clinician should test the CSF for albuminocytological dissociation which would allow the diagnosis of GBS with this atypical and rare variant of the disease.

text in

text in