Introduction

In many cases, decision making is a complex task for clinicians. It requires dealing with various aspects which impact the support process and developing strategies which are consistent with the care objectives, in order to go beyond simply providing information on the condition and treatment options. Tools for making complex decisions must be acquired. In this review, we discuss this process based on four determining factors: the doctor-patient relationship, assertive communication, the importance of the prognosis, and the definition of terminality; topics which are greatly feared and misinterpreted by patients, caregivers and professionals. This is especially true when dealing with advanced noncancer illnesses, as it is difficult to correctly determine the points which mark a global and irreversible deterioration, making it difficult to adjust the objectives and quality of care to the patient's status, wishes and preferences 1.

The doctor-patient relationship: The difficult patient

A satisfactory doctor-patient relationship is vitally important for making decisions. It is based on good communication, empathy, honesty and clear rules, facilitating the communication process and the discussion of end-of-life topics and the need for advanced life support.

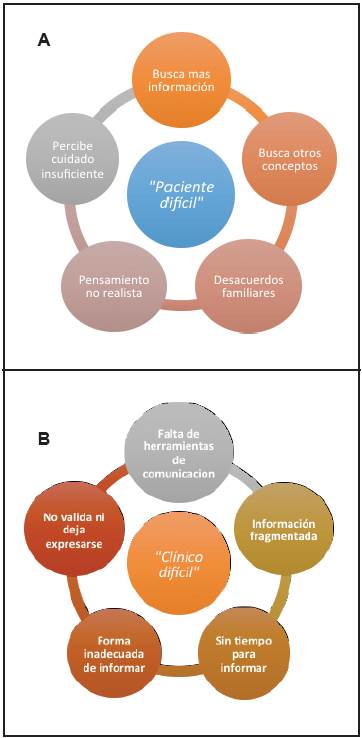

People usually refer to patients as "difficult" when they seek more information or request other medical (or even nonmedical) opinions when there are disagreements between the caregivers or even with the patients themselves, misinterpreting their questions and anxieties as a lack of understanding of the situation and as pressure or harassment of the physician who feels weary and stressed under these circumstances (Figure 1A). What generally happens is that the doctor-patient relationship and communication process are disrupted 1.

Likewise, we could speak of "difficult clinicians": those without training in communication skills; lacking empathy for their patients; who transmit fragmented information which is not consistent with the established plan of care; do not spend time clearly explaining the care process, progression and expectations of the disease and its treatment; are not aware of the patients' personal history, preferences and wishes; do not know how to provide information at the appropriate time and place; and, finally, do not validate the information received and do not allow emotions to be expressed (Figure 1B).

There is no evidence-based standard for managing the doctor-patient relationship. This is built gradually, and what is difficult for some clinicians is an opportunity for others 1.

Assertive and timely communication

Appropriate management of the communication process between the medical team and the patients and their families will help strengthen an optimal doctor-patient relationship and facilitate the decision-making process.

Communication requires the intention of both parts to share information; for this, it is important to introduce yourself, explain the goals of the meeting, determine the appropriate place and time, and begin by inquiring what the patient already knows and whether he/she wishes to receive more information. It is important to identify cognitive or emotional aspects or personality traits of the patients or their families which could interfere in the communication process, and recognize the need for psychological or psychiatric support. Based on this, caregivers can also be classified according to their ability to handle, understand and replicate the information. Information should be communicated completely, directly, clearly and honestly, and be consistent with the care plan, taking into account the patient's expectations and wishes, as well as his/her socio-cultural, religious and educational conditions, but it is important to recognize the limitations in predicting outcomes. A neutral tone should be used, repeating the key points, understanding that it takes time, even several meetings, to absorb the information and be able to make decisions. Finally, validate the patient's understanding of the information, answer any questions, and allow him/her to express his/her emotions, remembering the role of non-verbal language in the communication process 1-3. Only 7% of verbal information and approximately 40% of nonverbal information sticks with the patients after the first interview 1.

There are different strategies (like the "SPIKES" protocol) for delivering bad news which offer useful keys for improving the clinicians' skills 4.

Prognosis: Beyond a figure

Discussing the prognosis is one of the most difficult topics in the communication process and greatly influences decision making. Clinicians tend to fall into one of two extremes: avoiding the topic for fear of making a mistake or plunging into a generally uncertain prediction. Physicians are reported to overestimate the prognosis in approximately 30% of cases and underestimate it in 12% 5,6.

Clinicians should understand that the prognosis is not a certainty but rather an important element in dealing with the issues of what to expect with regard to the illness and its treatments, and planning appropriately 7.

The diagnosis of a chronic cancer or noncancer illness involves inevitable uncertainty for patients and caregivers. The patients want to know their prognosis, which becomes vitally important to them in determining a care plan. The physician should respond to these questions with reasonable certainty, without making a desperate leap in providing a figure of their remaining life expectancy. This discussion should rely on the care process to emphasize the various tipping points which indicate a negative disease course, allowing patients and caregivers to understand the situation, generate introspection on the disease, and be able to choose the appropriate type and site of care, respecting the basic ethical principles. Likewise, being aware of the prognosis improves communication within the medical team and allows a more timely palliative care intervention without causing care plan conflicts 5-9.

The prognosis should be determined based on elements such as the clinical estimate of survival based on the disease trajectory, the patient's functional status and the presence of symptoms which would mark a tipping point, such as dysphagia, dyspnea, anorexia or delirium 5. Specific biological parameters (hematological, hepatic, ventricular function or lung capacity) for each disease should be considered; these help evaluate the degree of organ dysfunction, which is related to survival. Finally, there are specific and nonspecific prognostic models for patients with chronic cancer and noncancer illnesses. These are based on the disease trajectory, functionality scales such as the Karnofsky or ECOG scales, prognostic indices and, in patients with noncancer chronic illnesses, specific scales with organ dysfunction parameters (NYHA for heart failure, Child-Pugh for liver disease, BODE for chronic pulmonary disease and FAST for dementia). Nonspecific scales are also applied, such as nutritional status, functionality, pressure sores, cognitive decline and infections, which have an additional impact on the risk of death 7,9-11.

There are difficulties in applying prognostic models to decision making in patients with advanced illnesses since these models are generally based on large populations and designed to identify patients at risk of dying, and therefore tend to not represent patients in the final phase of life 10.

Determining the prognosis of patients with noncancer chronic illnesses is difficult due to the wide variability in disease trajectory, the difficulty in accurately determining the point of no return, the unrealistic expectations of the patients and even the doctors themselves, and the perception of medical failure when the clinical condition deteriorates 5,10,11.

Discussing the prognosis when the decision is made to redirect the therapeutic efforts is another challenge for clinicians. The discussion in these cases should be focused beyond survival, since it could open the door to grasping at any minimal possible option, and should be related to the setting, proportionality, wishes, preferences and quality of life. When the prognosis is poor, the decision-making discussion should be aimed at knowing that the decision is going to influence "how the patient dies" rather than "whether the patient dies," since one of the main difficulties is the "fear of unplugging him/her," with the emotional burden this creates. For this, it is important to reinforce the family's support of the patient, not delay end-of-life discussions, avoid having a single person carry the decision-making burden and promote family consensus, provide psychosocial support to the caregivers, and prepare them for death and grieving, accepting death as a natural process 12.

Ongoing medical support plays a fundamental role in this goal. The attending physician is the one who understands the disease and its progression; knows the patient and his/her personal and family history; understands the crisis situations, responses, patterns of change and possibility of reversal; understands the limits and outcomes of interventions; and can determine an appropriate care plan, considering the patient's preferences and wishes, and avoiding disproportionate measures and unnecessary suffering 5.

The definition of "terminality" and its consequences

The definition of "terminality" is linked to the prognosis, and also deals with a great clinical challenge. The Spanish Society for Palliative Care defines "terminality" based on five criteria: 1. The presence of an advanced, progressive and incurable disease, 2. No possibility of response to specific treatment, 3. The presence of multiple intense, multifactorial and evolving symptoms, 4. A great emotional impact on the patient, family and healthcare team, and 5. A limited life expectancy, generally less than six months. Given the difficulty in identifying these criteria, overall assessment variables have been added for cancer and noncancer patients in order to detect and adjust the interventions provided in a more timely fashion (Table 1). These problems have also led to the introduction of "the surprise question" ("Would it surprise me if the patient were to die in the next 12 months?") in order to adapt care in a terminal situation 11.

Table 1 Variables associated with terminality in patients with chronic cancer and noncancer illnesses

| Chronic cancer | Karnofsky Index <40% |

|---|---|

| illnesses | Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) < 2 |

| Symptoms like anorexia, dyspnea, delirium and dysphagia | |

| Perceived poor quality of life | |

| Cognitive decline | |

| Lab results such as hypoalbuminemia, hyponatremia, leukocytosis, lymphopenia and hypercalcemia | |

| Chronic noncancer | Age |

| illnesses | Fragility |

| Comorbidities | |

| Duration of the disease | |

| Nutritional status | |

| Cognitive disorder | |

| Depression | |

| Lack of family and social support |

It is important to correctly identify a terminal state, as this affects the care plan in many aspects: focusing the treatment goals on adequate symptom control, maintaining dignity and privacy, conducting an appropriate communication process for each condition, strengthening the patient and family's participation in decision making, providing optimal care at the end of life and avoiding its unnecessary prolongation, implementing a timely transition of care to the preferred site, documenting the existence of advance directives, providing appropriate accompaniment, and preparing for death and grieving. Otherwise, the patient will be exposed to inappropriate interventions, valuable family time will be lost, and cultural and spiritual needs which are important in this stage will be excluded, preventing preparation for death and causing conflicts with the medical team in light of the outcomes (Table 2) 13.

Table 2 Consequences of correctly or incorrectly labeling a patient as terminal.

| Correctly labeled as terminal | Incorrectly labeled as terminal |

|---|---|

| Goals focused on controlling symptoms | Inappropriate resuscitation attempts |

| Respect for dignity and privacy | Interventions with no benefit |

| Appropriate end-of-life care | Limited family time |

| Care provided in the preferred site | Loss of trust in the medical team |

| Family preparation for death and grieving | Lack of preparation for death and grieving |

| Avoiding unnecessary interventions | Inconsistent information within the medical team |

| Avoiding prolonging the dying process | Poor control of end-of-life symptoms |

| Suffering and stress in the dying process | |

| Disagreements on the care plan | |

| Unmet cultural and spiritual needs |

Campos-Calderón C et al. evaluated the effect of determining a terminal state in 202 patients. They found that a terminal state was recorded a median of five days prior to death and 31.7% of the cases occurred within the final 48 hours. The recording of terminality had an impact on the number of interventions and on end-of-life decisions such as cardiopulmonary resuscitation, sedation and the use of opioids. Of the patients for whom a terminal status was not recorded, 70% had a noncancer chronic illness 14.

Dealing with a terminally ill patient involves an additional challenge in deciding to "limit treatment" or, better, "redirect treatment," as the first has the connotation of making no further efforts and "giving up the fight" 15, while "redirecting" leads to a thorough application of measures proportionate to the patient's condition, sparing no effort to control symptoms, provide comfort, and avoid suffering.

Several studies show that up to 73% of patients are admitted to intensive care with no clear survival benefit. They receive poor symptom management at the end of life and numerous decision-making conflicts occur, along with caregivers' doubts, fear and hopelessness 12,15.

One of the biggest difficulties in these situations is related to the capacity for making decisions, which is often compromised, with decisions needing to be made by relatives or proxies. First, the existence of advance directives should be determined; second, whether the patient has provided any recommendations for decision making; or last, the representative must choose based on the patient's greatest good 12-18.

A non-systematic review of treatment redirection in intensive care performed by Bueno Muñoz M found that, in 90% of cases, the initiative to redirect treatment was taken by the physician and, in 28.3% of cases, the relatives were not involved in the decision. A poor disease prognosis, suffering and subsequent quality of life, in that order, were the main reasons. Sixty percent of patients over the age of 65 did not know about advance directives. Finally, 17.3% of the nursing staff compared it with passive euthanasia and 84.6% considered that prescribing is not the same as withdrawing 15.

Making decisions about treatment redirection requires a suitable time and place to explain in a continuous, clear and coherent fashion how the whole care process has been implemented; the goals of the interventions in accordance with the patient's condition, wishes and preferences; and their impact on quality of life. Families should not be approached to decide what must be done, and measures considered to be of little benefit, or which do not coincide with the planned goals, should not be proposed. On the contrary, the clinician should provide families with guidance and recommendations to reach realistic expectations and choose better care. Insufficient information or inappropriate language decreases the possibility of making informed decisions and affects trust in the medical team 12.

Strategies used for decision making

Mixed-focus clinical guidelines are generally used, taking elements from probability models, available technology and clinical balance. They also consider overall progressive deterioration more than an assessment at a single point in time 5, as well as the patient's wishes and preferences, family dynamics and cultural and religious aspects.

Clinical guidelines, however, have limitations in patients with advanced illness and in elderly patients with multimorbidity. They focus on dealing with each individual illness and starting medication, but not on when to not start it or to stop it. This leads to polypharmacy with its consequent economic and social-familial burden of treatment. They emphasize the use of clinical judgement and respect for the patient's preferences and wishes, but do not specify tools for this, nor do they consider the participation of caregivers nor the cognitive impairment which is so common in the elderly population 16.

Formiga F et al. analyzed decision making in 293 patients with terminal noncancer illness at the end of life, finding that only 37% had been talked to about resuscitation orders, 18% had graduated orders proportionate to their condition, 57% of the families had received information on the patient's process and prospects, the withdrawal of medications not related to care goals had been considered in 56% of patients and was carried out a mean of 1.2 days prior to death, and participation in palliative care was requested in 65% of cases, but was implemented a mean of 1.5 days prior to death 17.

Decision making should be based on the following equation: Illness + Degree of progression + Degree of overall deterioration + Severity of crises + Patient and family expectations and wishes. Added to this should be timely meetings to discuss end-of-life topics, and an assessment of the patient's ability to make decisions and the dynamics guiding this ability, whether individual or familial, based on the different roles and values which make up his/her network of caregivers, avoiding an emotional overload, guilt or remorse 1,11.

Jansen J et al. suggest a structure for making complex decisions in patients with multimorbidity based on four questions: 1. What do we know about the patient's wishes and preferences? Focusing on an assessment of their decision-making capacity. 2. Will the intervention be effective? Whether it resolves the specific situation. 3. Is the intervention in line with the patient's wishes and preferences? Whether it maintains a quality of life in line with the patient's wishes. And lastly, 4. Does the intervention weigh the risk/benefit ratio? Are the benefits greater than the risks? 18.

Conclusions

Decision making in patients with advanced chronic illnesses is a complex process requiring a satisfactory doctor-patient relationship and a dynamic educational process including timely meetings to carry out a continuous assessment over time, detecting the degree of gradual and functional progression related to non-reversibility. It is incorrect to think that an open and honest discussion destroys patients' and families' hope and causes psychological harm. It is important to be able to deal with determining factors for end-of-life decision making and recognize the limitations of models and clinical guidelines for this process.

texto em

texto em