Introduction

Diabetes mellitus, along with cardiovascular diseases, cancer and respiratory diseases, is part of a public health interest group known as chronic noncommunicable diseases (CNCDs). In and of itself, it is responsible for 1.6 million deaths per year 1, being the seventh cause of death in the United States 2, with clear evidence of an accelerated growth in its prevalence in developing countries 3. In Colombia, in 2015, the prevalence of type 2 diabetes mellitus was 9.6% 4.

Diabetes mellitus treatment is based on three pillars: nonpharmacological measures, diabetes education and medications. Nonpharmacological management seeks to achieve lifestyle changes leading to permanent metabolic control through normalizing and maintaining weight (diet) and a persistent increase in physical activity. The educational program supports nonpharmacological management so the patients can modify their lifestyle and achieve the treatment goals. Finally, pharmacological treatment should be specific and personalized 5,6.

Inappropriate or no treatment increases the likelihood of micro and macrovascular complications like cardiovascular disease, diabetic retinopathy, kidney disease, diabetic neuropathy and diabetic foot 7, and therefore disease control should be early, effective and sustained 8.

Despite this, there are difficulties in patients adhering to treatment. There are many reasons for poor adherence: side effects of the medications, the complexity of the treatment plan, not remembering, the distance to the care site, as well as sociodemographic factors like educational level and monthly income 9,10.

Lack of adherence has become a big problem, as this is essential for patients' health recovery and maintenance. The adherence of patients with chronic illnesses in developed countries is, in the best of cases, 50%, and six months after beginning treatment, only 20 to 70% still take it 11. For diabetes mellitus, adherence to diabetes treatment plans has been recognized as a key factor in its control and the prevention of complications and fatal outcomes 12-18. An impact has also been shown on its direct and indirect care costs 19,20.

Therefore, the World Health Organization has created a guide for dealing with lack of adherence, presenting guidelines for its control. It proposes five groups of factors, or dimensions, of adherence: 1) socioeconomic, 2) healthcare system/healthcare provider -related, 3) disease-related, 4) treatment-related and 5) patient-related 21-23.

In light of this problem, new strategies and care models are essential to improve the adherence of patients with diabetes mellitus in its different dimensions 24. These new strategies include those supported by information and communication technologies (ICTs), for example, telemedicine. Several studies have shown a positive impact on adherence, knowledge of the disease, therapeutic lifestyle changes and self-care 25-34. The objective of this study is to answer the following question: In patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus, what ICT-based care alternatives support treatment adherence, compared with usual care?

Data collection

A systematic review of the literature was performed following the Cochrane guidelines and presented in line with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) recommendations. A search was performed of the following databases: Medline, Embase, Scopus and LILACs, using MeSH, Emtree and free-text terms with the following key words: telemedicine, tele-monitoring, treatment adherence and type 2 diabetes mellitus. The search was done by the first author in English and Spanish (Annex 1), supported by a librarian. Experimental (controlled clinical trials), quasi-experimental (pre-post) or cohort observational studies from January 2008 through December 2018 were included. Studies without a comparison group, those that did not evaluate adherence or did not include results (clinical trial protocols), type 1 diabetes patients, minors or studies which were not published in full text were excluded. Both authors searched for and selected the articles independently. Any differences were resolved by consensus. The selected articles were evaluated for bias by the second author, in five categories: random sequence generation, sequence masking, incomplete outcome data (patient attrition), selective reporting and others. Given the characteristics of the intervention and outcome, intervention blinding was omitted.

Data extraction was performed independently by both authors, and differences were resolved by consensus. The information obtained included the title, author, year, design, population, scale of the approach, type of measurement, method used, technology used and outcome. Review Manager 5.3 (Copenhagen: The Nordic Cochrane Centre, The Cochrane Collaboration, 2014) was used for data management. The results were organized in a table for presentation. Neither meta-analysis nor sub-group analyses were performed.

As this was a secondary source study, research ethics committee approval was not required. The authors participated in preparing the manuscript and reviewed the result prior to submitting it for publication.

Results

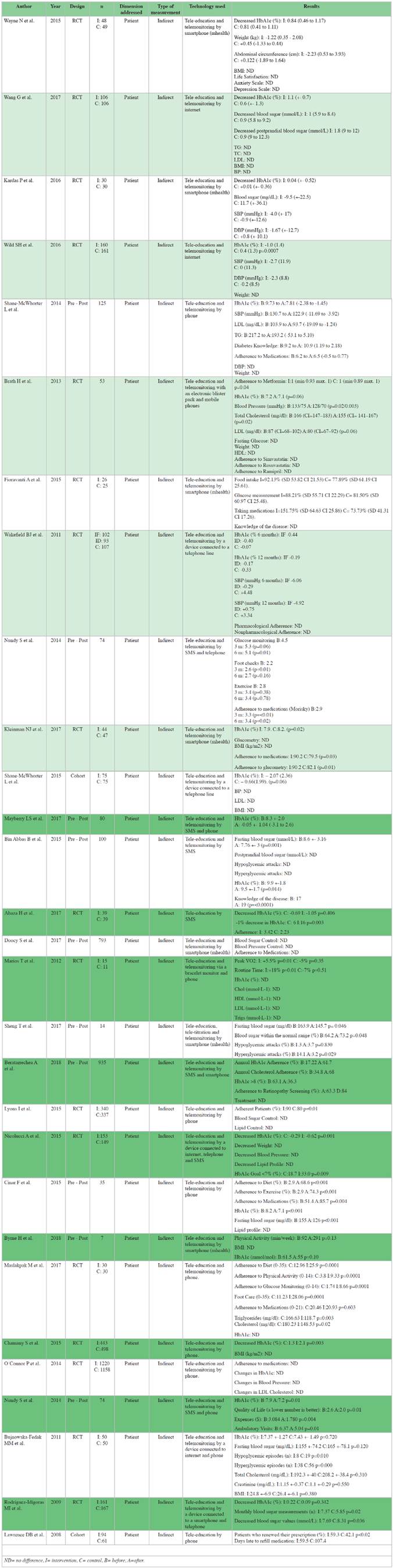

The search yielded a total of 466 studies, and 29 articles were included in the study (Figure 1). Of these, 17 (59%) were RCTs, 10 (34%) were pre-post studies and 2 (7%) were cohort studies (Table 1). The studies' bias assessment is reported in Figure 2. Blinding was not assessed in most cases, since it is very difficult for the intervention to be hidden from patients and investigators. Almost half of the studies had difficulties with patient attrition (n=21) or did not have an adequate description of the methods for random group assignment (n=11).

All of the studies (n=29) deal with the problem of adherence in the "patient-related" dimension; that is, they address the patients' knowledge of the disease, lifestyle and habit modification, self-administration of treatment and improved motivation for self-care.

None of the studies measured adherence directly. The study by Brath et al. 40 came the closest, using an electronic blister pack that sent a signal when the medication was removed. In 28 studies (96.5%), the main method used to measure adherence was a questionnaire. The questions were aimed at information on glycemic control (blood glucose measurements), vital signs (blood pressure, weight, height, BMI), knowledge of the disease, adherence to pharmacological measures (taking the medications) and nonpharmacological measures (exercising or following the diet) and monitoring medical variables.

To measure the effectiveness of the intervention, nine studies (31%) only used physiological markers like HbA1c, lipid profile or blood sugar. Two studies (7%) used pharmacological and nonpharmacological adherence scales, and 18 studies used both (62%).

Of the studies that used HbA1c as an outcome, 68% (15/22) showed a statistically significant reduction in HbA1c levels after the intervention. Ten studies measured fasting blood sugar, with six (60%) reporting a statistically significant reduction in fasting blood sugar after the intervention.

Fourteen studies measured pharmacological adherence. Thirteen (92.9%) used a questionnaire and one (7.1%) used an electronic blister pack. Sixty-four percent of these studies showed a statistically significant improvement in pharmacological adherence levels after the intervention. In the 16 studies which measured nonpharmacological adherence, this was done through a questionnaire. In 13 (81%) of these studies there was a statistically significant improvement in nonpharmacological adherence levels after the intervention.

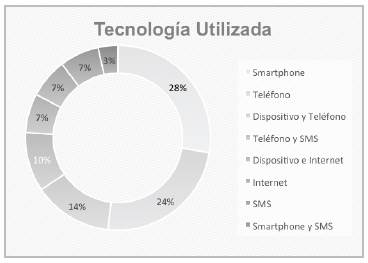

All of these studies used technology differently. Some studies used only one technology, while others used a combination of several. The most frequently used technology was the smartphone (n=8; 27.6%) and conventional phone (n=7; 24.1%) (Figure 3).

Regardless of the technology used, in addition to telemonitoring, all of the interventions were accompanied by health tele-education (n=29). Only 16 (55%) explained the type of tele-education they provided. These topics were framed within information about the disease such as its causes, medication side effects, associated comorbidities, foot care and how to detect episodes of hypo and hyperglycemia; motivation for physical activity and health eating; helping change the negative perception of the disease, anxiety or stress; persuasion to generate self-control over constant blood sugar measurement, both fasting and postprandial, and its normal values; and HbA1c, blood pressure and lipid profile goals. Furthermore, patients received information and reminders on taking their medications, monitoring glucose, exercise, nutrition and foot care.

Discussion

This literature review found that several types of technology are used to support treatment adherence in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus, with smartphones or conventional phones being the tools most often studied. These data coincide with the study by Lerman et al. 41 which showed that monthly telephone calls to promote self-care behaviors and detect and try to solve problems related to diabetes control improved adherence to diet and pharmacological treatment. Another study by Vervloet M et al. 42 used SMS to impact on adherence over one year of follow up and showed significant improvement compared with the control (79.5 vs. 64.5%; p<0.001). After two years, the improved adherence in the SMS group persisted and remained significantly higher than in the control group (80.4 vs. 68.4%; p<0.01).

We found that the use of smart mobile devices, conventional phones, connected biomedical devices, web pages or text messages have proven to be useful in positively impacting adherence to diabetes treatment, as shown by Huang Z et al.'s meta-analysis (43), but it is notable that all of the analyzed studies are aimed at patient-related factors. However, other factors impacting adherence cannot be overlooked, such as socioeconomic, healthcare system, disease and treatment factors, as considered by WHO 22. It would be interesting to evaluate the impact of ICTs on these other dimensions of adherence.

A study by Cheong C et al. 44 analyzed pharmacological adherence to two comparable types of diabetes medications with different prices, showing that the cheaper medication generated more adherence, but they did not use ICT. It is likely that the other dimensions are not as easily addressed with the use of ICT. In a case-control study in which patients' co-pays were reduced, 36.1% had a higher likelihood of being adherent (OR: 1.56 [95% CI: 1.04-2.34]; p=0.03) 45 and they did not use ICT, either.

The studies were found to have poor methodological quality, as occurs with most telemedicine studies, as shown by Huang Z et al. 43 and Zhai YK et al. 46 in different meta-analyses. Therefore, it is important for research teams to develop strategies to strengthen the methodological quality of telemedicine studies.

The analysis showed that the main technologies used are smartphones and conventional phones. With the growing number of smartphones, it is estimated that, in the next 10 years, 80 to 90% of people in developed countries will have these devices, thus facilitating remote and more efficient interaction with the healthcare team. This is a great opportunity to design models to leverage treatment adherence for type 2 diabetes using this type of technology, as shown by Boulos et al. 47 and Klasnja et al. 48.

One of the limitations of this study is that grey literature (congresses, seminars, bibliographic references) was not searched. However, the most important databases were included, like Medline, Embase, Scopus and LILACS. Another limitation is that only one author performed bias assessment. However, this author is experienced in critical appraisal of the literature, which reduces the risk of bias.

The use of ICTs is unequal, depending largely on each country's level of development. A bibliographic search of the use of these technologies in diabetes management and the improvement of adherence in Latin American countries or Spain yields very few studies, with more studies found in other parts of the world. This limits decision making aimed at our developing countries. We must continue with the research line of controlled studies to provide evidence of the usefulness of these new tools in our setting 49.

Conclusion

In the analysis of the problem of lack of adherence as a significant cause of inadequate type 2 diabetes mellitus treatment, the studies we found showed that various ICTs, but especially smartphones and conventional phones, can help solve this problem. In all cases, the approach was aimed at patient-related factors, perhaps due to the fact that this type of technology is applied to people and not to the other dimensions affecting adherence. Management with this type of technology should be aimed at improving knowledge of the disease, empowerment, motivation and self-care. In any case, very little evidence was found, and more studies are needed to improve decision making regarding the solution to this problem.

texto en

texto en