Clinical case

A 68-year-old man was seen by infectious disease in the outpatient department for a recent diagnosis of HIV infection. He had consulted 15 months prior for unintentional weight loss (30 kg) associated with weakness and fatigue. Coupled with this, he had had a productive cough for six months, without dyspnea or other related symptoms. He denied temperature abnormalities, night sweats, dyspnea or gastrointestinal symptoms. However, two days prior to the outpatient consult he had had an unquantified fever, sweating and diaphoresis.

He had a history of type 2 diabetes mellitus diagnosed three months prior, with a glycosylated hemoglobin of 10.1%; demyelinating sensory polyneuropathy in the lower extremities of unknown etiology, which was being studied; systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) since four months prior, apparently diagnosed due to suspected lupus nephritis, with no histopathological studies; and immune thrombocytopenia. He was taking deflazacort 30 mg (with no initiation date specified), enalapril 2.5 mg/day, atorvastatin 20 mg/night, and carvedilol 6.25 mg every 12 hours. He had also been prescribed hydroxychloroquine and mycophenolate mofetil to treat the lupus, as well as metformin + sitagliptin and insulin (he did not remember the dose), which the patient had not started to take.

On physical exam, he was febrile, tachycardic, tachypneic and had a borderline low oxygen saturation (88-90% at 2,500 m.a.s.l.). He had bilateral enlarged, nontender axillary lymph nodes smaller than 2 cm, with no other notable physical exam findings. His height was 1.73 m and his weight was 60 kg. He was admitted to the hospital for more tests.

After admission, the patient provided the ambulatory laboratory tests recorded in the medical chart, which can be seen in Table 1. The admission laboratory tests are found in Table 2. (Acta Med Colomb 2022; 48. DOI:https://doi.org/10.36104/amc.2023.3008).

Table 1 Laboratory tests prior to admission.

| Date | Lab test | Value |

|---|---|---|

| 03/08 | ANAs | Positive (value not reported in the clinical chart) |

| Anti-DNA | Positive: 453 IU/mL | |

| ENAs | Reported as negative | |

| C3 | 108 mg/dL (80-143 mg/dL) | |

| C4 | 9.10 mg/dL (15-48 mg/dL) | |

| 05/10 | HbA1c | 10.1% |

| 06/16 | HbA1c | 5.1% |

| 07/01 | HBsAg | Nonreactive |

| HCV Ab | Nonreactive | |

| HIV rapid test | Reactive | |

| Direct Coombs | Positive (number of "+" not speci fied) | |

| 07/07 | HIV (the type of test is not specified) | Reactive |

| Lambda serum free light chains | 126 mg/dL (3.3-19.4) | |

| Kappa serum free light chains | 298 mg/dL (5.7-26.3) | |

| Ratio | 2.36 | |

| ALT | 27 U/L | |

| AST | 35 U/L | |

| 07/21 | Leukocytes | 3,670 /mm3 |

| Neutrophils | 2,140/mm3 | |

| Lymphocytes | 1,240/mm3 | |

| Hemoglobin | 12.1 g/dL | |

| Hematocrit | 35.4% | |

| Platelets | 29,000/mm3 | |

| Creatinine | 1.11 mg/dL | |

| BUN | 17.24 mg/dL | |

| Potassium | 3.9 mEq/L | |

| Sodium | 129 mEq/L | |

| 07/21 | HbA1c | 4.45% |

| 24-hour proteinuria | 886 mg |

Table 2 Laboratory tests on admission.

| Lab test | Value |

|---|---|

| Leukocytes | 4,910/mm3 |

| Neutrophils | 3,110/mm3 |

| Lymphocytes | 1,450/mm3 |

| Hemoglobin | 10.2 g/dL |

| Hematocrit | 34.5% |

| MCV | 81.7 fL |

| MCH | 26.5 pg/c |

| Platelets | 97,000/mm3 |

| Creatinine | 0.76 mg/dL |

| BUN | 28.78 mg/dL |

| Potassium | 4.05 mEq/L |

| Sodium | 126.9 mEq/L |

| Chloride | 96.94 mEq/L |

| pH | 7.52 |

| PCO2 | 28 mmHg |

| HCO3 | 22.9 mEq/L |

| BE | 0.6 mEq/L |

| PO2 | 62 mmHg |

| PAFI | 258 mmHg |

| FIO2 | 24% |

| Lactate | 1 mmol/L |

| Albumin | 2.1 g/dL |

| Total protein | 7.41 g/dL |

| Direct bilirubin | 0.26 mg/dL |

| Indirect bilirubin | 0.36 mg/dL |

| Total bilirubin | 0.62 mg/dL |

| SGOT/AST: | 28.83 U/L |

| SGPT/ALT: | 33.31 U/L |

| Urinalysis | pH 6, blood: approximately 200, protein: 30 mg/dL Sediment: epithelial cells 0-2/hpf, leukocytes 0-2/hpf, erythrocytes 8-10/hpf, 100% crenated, bacteria +, granular casts 0-1/hpf, amorphous urate crystals ++, calcium oxalate crystals ++ |

| Direct bilirubin | 0.26 mg/dL |

| Indirect bilirubin | 0.36 mg/dL |

| Total bilirubin | 0.62 mg/dL |

Specialist

This was a 65-year-old patient with unintentional weight loss and lingering respiratory symptoms over the last six months. He was admitted due to acute febrile syndrome with a full-blown systemic inflammatory response. The history of new-onset SLE in a man over the age of 50 is notable, as is his lack of other symptoms in the presence of thrombocytopenia and kidney disease (not yet biopsied), making this diagnosis unlikely. In fact, when a patient has recently been diagnosed with SLE and HIV, the first diag nosis should be questioned, as the association of HIV with autoimmune disease is inversely proportional; that is, as HIV immunosuppression worsens, autoimmune disease shuts down; when the immune status improves, the symptoms of rheumatic disease may increase. In fact, the combina tion of lupus and HIV is rare: in a review of case reports up to 2015 in English literature, only 79 cases were found, with a very low prevalence of simultaneous diagnosis 1. Furthermore, we must consider that some infections, like HIV 2, tuberculosis 3 and other acute bacterial or fungal infections may cause false positives on autoimmune tests like antinuclear antibodies (ANAs) or anticardiolipin antibodies and, occasionally, anti-DNA antibodies 4. Thus, consider ing the lack of significant signs and symptoms of SLE, this condition is not likely.

Given his age and weight loss, in addition to the HIV infection, lymphoproliferative neoplasms should be included in the possible diagnoses. While these neoplasms would explain this patient's chronic picture, they would not explain the respiratory symptoms and acute febrile syndrome, as these symptoms would point more to an infectious disease which, given the short-term prognosis, would require ac tively searching for these diseases.

A myriad of symptoms and paraclinical findings in the patient may be confusing and suggest several diagnoses; when they are all grouped, progressive immunosuppression can be seen. The weight loss leads us to think of a wasting syndrome related to HIV; hyponatremia is very common in patients hospitalized for AIDS [up to 80% 5]; neuropathy is also a relatively frequent finding, especially with a CD4 between 200-500; kidney disease manifested as proteinuria can also be explained by HIV, although in this case this is considered a diagnosis of exclusion. Finally, the patient is on high-dose corticosteroids and has HIV infection in a currently unknown stage and, therefore, this patient is probably severely immunocompromised; thus, given his febrile syndrome and chronic lung symptoms, tuberculosis and opportunistic germs should mainly be suspected, in this case, histoplasmosis, pneumocystis and cryptococcosis are increasingly likely. Other opportunistic infections are less frequent (blastomycosis, coccidioidomycosis) or are diagnoses to be ruled out in severe immunosuppression (cytomegalovirus), but especially because they require a history of specific geographical exposure. Weighing the incidence, the most probable diagnosis is either tubercu losis or histoplasmosis, with the latter being more likely given the thrombocytopenia, which is a frequent finding in this disease, both in immunosuppressed 6 as well as immunocompetent 7 individuals. In these patients, it is not unusual to find almost as many diagnoses as symptoms, with many positive paraclinical tests that cause great confu sion and, many times, have a different diagnosis depending on the specialty evaluating them, determined by who is on call 8,9.

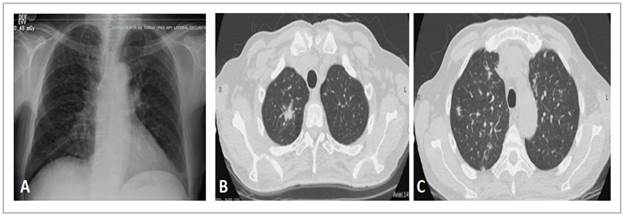

MODERATOR: a chest x-ray and tomography were taken, which are shown in Figure 1.

Pulmonology

The chest x-ray shows interstitial opacities and mediastinal widening (Figure 1A); in immunocompromised patients, x-rays do not have good specificity or sensitivity for detecting respiratory diseases and differentiating among them. The chest HRCT shows random or diffuse micronodules (Figure 1C), although the centrilobular ones are most evident, associated with solid nodules, especially a spiculated one in the right upper lobe (Figure 1B). Micronodules with this distribution suggest hematogenous dissemination and generate a differential diagnosis of miliary tuberculosis, histoplasmosis and other fungal infections like candidiasis and disseminated blastomycosis; hematogenous metastasis of extrapulmonary tumors is also included, especially thy roid, melanoma, breast and kidney tumors 10.

On the other hand, nodules like the ones seen in the im ages are suggestive of tuberculosis and fungal infections, especially cryptococcosis; when they are surrounded by ground glass opacities, one of the differential diagnoses is Kaposi sarcoma.

MODERATOR: during hospitalization, the patient had a stable course with a trend toward improvement and he un derwent fiberoptic bronchoscopy with a biopsy, as well as an axillary lymph node biopsy. The results of the remaining di agnostic studies and pathology reports are shown in Table 3.

Table 3 Advanced blood tests, autoimmune disease test profile, with pathology study results at the end.

| Test | Value |

|---|---|

| C3 | 65 (80-143 mg/dL) |

| C4 | 10.2 (15-48 mg/dL) |

| ANAs | Positive, fine speckled pattern, 1/320 dilution |

| AntiDNA antibodies | Negative |

| Direct Coombs | 3+ |

| Haptoglobin | < 8 mg/dL |

| Viral load | 7,450,543 copies/mL (HIV-1 RNA/mL) Logarithm: 6.87 |

| Beta 2 Microglobulin | 10.38 mg/L (less than 2.6) |

| Kappa serum free light chains | 330 mg/L (3.30 - 19.4 mg/L) |

| Lambda serum free light chains | 150.89 mg/L (5.71 - 26.3 mg/L) |

| Free light chain ratio | 2.187 (0.26 - 1.65) |

| Histoplasma urine antigen | 2.6 (positive) |

| Cryptococcal serum antigen | Negative |

| Cytomegalovirus viral load | Negative |

| Fiberoptic bronchoscopy: | 09/01/2021: PCR for Mycobacterium tuberculosis: Detected in BAL. |

| Bronchoalveolar lavage: Growth of Myocobacterium tuberculosis (17 days) | |

| Bone marrow biopsy | Flow cytometry: Decreased helper T cells, slight plasmacytosis with no abnormalities and scant B lymphocytes with no light chain expression. The mature B lymphocytes are positive with CD19/CD20, no clear expression of kappa/lambda light chains and no CD5 expression. Biopsy: Negative for tumor infiltration. Hypercellular marrow, with erythroid hyperplasia and plasmacytosis (normal plasmacyte phenotype, <10%). |

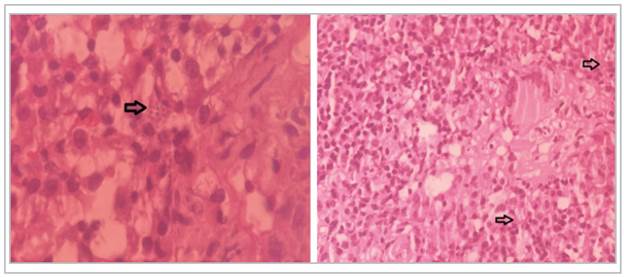

| Axillary lymph node biopsy | Diffuse lymphohistioplasmacytic inflammatory infiltrate. Scant round, stippled, phagocytized structures suggestive of Histoplasma yeast. |

Expert

The new autoimmune laboratory tests do not contribute much, as they can be affected by the infectious process and current immunosuppression. Light chains are elevated and there is a polyclonal pattern on protein electrophoresis, compatible with an active inflammatory process. Beta-2 microglobulin was used at the beginning of the HIV pan demic as a serum predictor of AIDS progression 11; this explains why it was five times higher than the cut-off value in this patient.

The patient's final diagnosis is miliary tuberculosis and disseminated histoplasmosis coinfection within the clini cal context of HIV infection in the AIDS stage. The urine Histoplasma antigen has good sensitivity and specificity (approximately 90%) for diagnosing disseminated histoplasmosis in patients with HIV immunosuppression 12. Given the diagnostic characteristics of the serum cryptococcal antigen test, the negative result allows us to rule out this infection 13.

Tuberculosis - histoplasmosis coinfection is not uncommon in patients with HIV in the AIDS stage. In French Guinea and Panama, reports of the prevalence of tuberculosis coinfection in patients with disseminated histoplasmosis and HIV range from 8 to 15%. In Latin America, the prevalence varies significantly, and there are two studies in Colombia reporting a prevalence of 16% 14 and 34% 15 for tuberculosis coinfection in patients with histoplasmosis and HIV. A study in Medellín studied 14 patients with this coinfection, finding that most were men (85%), with a median age of 36 years, a median CD4 count of 70, a median viral load of 231,393 copies/mL, a third had another opportunistic infection and the most common symptoms (over 60%) were weight loss, anemia, fever, pulmonary infiltrates on chest x-ray, enlarged lymph nodes, hepatomegaly and elevated LDH. A third of the patients had thrombocytopenia 16.

The initial therapeutic decision in these patients, before having definitive diagnoses, is not simple. The picture is clouded by the fact that, even with histopathological stud ies, the diagnosis of tuberculosis may be elusive. Generally, in an HIV patient with these characteristics and symptoms and a chest tomography showing centrilobular or diffuse nodules, anti-tuberculosis treatment may be started em pirically. Given the characteristics of the symptoms and the imaging findings, these patients do not usually require empirical antibiotic treatment for common germs; the most difficult decision ends up being the empirical beginning of antifungal treatment, which should be done according to the probability of this coinfection, according to the clinical history and laboratory findings like thrombocytopenia and other cytopenias.

Finally, tuberculosis/histoplasmosis coinfection is not only important from the perspective of prognosis and initial treatment, but also forces the treating physician to carefully prescribe antitubercular and antifungal agents to avoid drug interactions; the problem is even greater when the patient is a candidate for beginning antiretroviral treatment. The following potential interactions are considered:

Antitubercular and antifungal drugs: rifampicin (one of the four medications indicated for initial treatment of tuberculosis in Colombia) interacts with itraconazole, which acts as a maintenance therapy for histoplasmosis; it does so by inducing P450 cytochrome activity, which increases metabolism of the antifungal agent, reducing it to even undetectable levels 17. The World Health Organization recommends considering the following options: prolonging amphotericin induction, increas ing the dose of itraconazole and monitoring its blood concentration, changing to another azole, or substituting rifampicin with rifabutin (which is not very available); several authors have proposed changing rifampicin to a quinolone 16,18.

Antifungal and antiretroviral drugs: non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors (NNRTIs) like efavirenz and nevirapine are cytochrome P450 inducers, decreas ing the concentration of itraconazole. Protease inhibitors like lopinavir and ritonavir increase the concentration of itraconazole; these considerations should be taken into account when beginning antiretroviral treatment 19. The patient was given amphotericin B for histoplasmosis treatment induction and began the RHZE four-drug combination to treat tuberculosis. When maintenance treatment with itraconazole was prescribed, the antitu bercular treatment was modified, withdrawing rifampicin and beginning moxifloxacin. He was discharged home when he finished the antitubercular and antifungal treat ment, began antiretroviral treatment, had rheumatological disease ruled out and, since then, has not needed to further hospitalization.

The clinical course and reasoning applied to this patient's case is interesting not only due to the cognitive component required to solve it, but also due to the integration and interpretation of a large quantity of existing data which inevitably leads to confusion. As mentioned previously, this was a patient with a myriad of symptoms, signs and positive paraclinical tests, who also appeared to have a myriad of diagnoses. This case recalls the endless tension in medicine between two opposite and equally valid maxims; in this case, between the maxim extrapolated from Occam's philosophy, or Occam's razor: "Entities should not be multiplied (or plu rality proposed) beyond what is necessary;" and the response given in the 20th century, attributed to Hickam: "a patient may have as many diseases as he pleases," or the law of plenitude 20,21. As clinicians dedicated to the diagnostic exercise, internists should be flexible and fluctuate between these two extremes, remembering that there are middle points like this case, which satisfy all maxims: seen from a strictly microbiological perspective, the patient has three diseases, or all those he pleases; seen from a pathophysiological point of view, the patient has one disease - advanced HIV infection - and the rest are explained by its biological course and resulting immunosuppression.

Figure 2 Lymph node biopsy report with (left) and without (right) magnification; diffuse lymphohistioplasmacytic inflammatory infiltrate can be seen. A few round, stippled, phagocytized structures suggestive of Histoplasma yeast (arrows). (Picture taken by Dr. Oscar Andrés Franco - Hospital Universitario Nacional).

texto em

texto em