Services on Demand

Journal

Article

Indicators

-

Cited by SciELO

Cited by SciELO -

Access statistics

Access statistics

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in

SciELO

Similars in

SciELO -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Anuario Colombiano de Historia Social y de la Cultura

Print version ISSN 0120-2456

Anu. colomb. hist. soc. cult. vol.38 no.1 Bogotá Jan./June 2011

Modernization Theory Revisited: Latin America, Europe, and the U.S. in the Nineteenth and Early Twentieth Century

Una revisión de la teoría de la modernización: América Latina, Europa, y los Estados Unidos en el siglo XIX y principios del XX

FERNANDO LÓPEZ-ALVES

Universidad de California

Santa Bárbara, Estados Unidos

lopez-al@soc.ucsb.edu

Artículo de reflexión.

Recepción: 17 de diciembre de 2010. Aprobación: 16 de febrero de 2011.

ABSTRACT

Theories of modernization, globalization, and dependency have assigned a clear role to Latin America: the region has been seen as dependent, exploited, and institutionally weak. In these theories, modernization and globalization are seen as forces generated elsewhere; the region, in these views, has merely tried to "adjust" and "respond" to these external influences. At best, it has imitated some of the political institutions of the core countries and, most of the times, unsuccessfully. While there is very good empirical evidence that supports these views, the essay argues that these theories need some correction. Latin America has been an innovator and a modernizer in its own right, especially in its cutting-edge design of the nation-state and in its modern conceptualization of the national community. Thus, the essay suggests that the region has not merely "adjusted" to modernization and globalization. Rather, the paper makes a case for a reinterpretation of the region's role as a modernizer and an important contributor to the consolidation of the modern West.

Key Words: Europe, globalization, Latin America, modernization, nation-state, United States.

RESUMEN

Las teorías de la modernización, globalización y dependencia han asignado un papel claro a América Latina: la región se ve como dependiente, explotada e institucionalmente débil. En dichas teorías, la modernización y la globalización se miran como fuerzas generadas desde fuera de la región. Así, América Latina solamente ha tratado de "ajustarse" y "responder" a esas influencias externas. Cuando más ha imitado algunas instituciones políticas de los países centrales y, en la mayoría de los casos, con poco éxito. Si bien existe evidencia empírica para sustentar aquellas perspectivas, este artículo argumenta que ellas necesitan ser revisadas. América Latina ha sido innovadora y modernizadora en sus propios términos, especialmente en el crucial tema de la construcción del Estado-nación y en su conceptualización moderna de la comunidad nacional. Por tanto, el artículo sugiere que la región no se ha limitado a "ajustarse" a la modernización y a la globalización. Por el contrario, en estas páginas se insiste en la reinterpretación del papel de la región como modernizadora y en su importante contribución al Occidente moderno.

Palabras clave: América Latina, Estado-nación, Estados Unidos, Europa, globalización, modernización.

MODERNIZATION, DAVID APTER surmised in the late 1960s, is "(...) a special kind of hope. Embodied within it are all the past revolutions of history and all supreme human desires. The modernization revolution is epic in its scale and moral in its significance. Its consequences may be frightening. Any goal that is so desperately desired creates political power, and this force may not always be used wisely or well."1 Apter was of course referring to 1960s expansion of capitalist development, from core to periphery. Like many other modernization theorists of his time, he thought of modernity as the spread of Western influence, from North America and Western Europe to the rest of the world.

What did modernity mean? Several indicators were listed: the development of an industrial advanced sector, the breakdown of peasant economies, the spread of wage labor, urbanization, the pace of economic development, the capacity of countries to generate savings, and the emergence of more open and democratic forms of rule. Core countries generated most of it; developing countries adjusted. Was this representation accurate? Latin America shows that it is not. Important institutional developments associated with modernity were also part of this picture but were not given as high a status: the relation between nation and state (needed to construct the nation-state category), and the modern characteristics of national identity. As we shall see, in this last sense Latin America made a solid contribution to modernity.

Work on culture, gender, and identity has challenged definitions of development and modernization, but our thinking about the spread of modernity and globalization has not substantially changed. Since the eighteenth and early nineteenth century, literature has depicted a causality that goes from an industrialized and more developed core to the "peripheries". The same has been claimed of "civilization", another fuzzy term associated with the expansion of the modern West. It can be argued that already in the 15th century Ferdinand and Isabella, the Catholic Spanish monarchs, wanted to civilize the Indies.2 Thus, development, modernity, and civilization have been conceived as spreading from Western Europe and North America to the rest, from first modernizers to late modernizers, from industrial to less industrial, from superior cultures that encouraged entrepreneurship, technological innovation and economic achievement, to others that did not and, thus, lagged behind.

The Europe-Latin America connection, during and after the colony, became the main independent variable in theories of Latin American development and modernity. As has been amply documented, colonialism made the region dependent, debt-ridden, and vulnerable. It was Marxist literature that made one of the most radical arguments from this perspective. Latin America was seen as a byproduct of Europe and, for better or for worse, of Spain, with its scarce capitalist development and accumulation. The region was said to have inherited the European feudal mode of production. Class struggle took place in the context of protracted feudalism. With no industrial revolution to speak of, Latin America's modernity was structurally hampered from the start. Influential Marxists such as Mariátegui in Peru or Puiggros in Argentina claimed so, generating a whole body of scholarship.3 While the "material basis" of the feudal lords in the new and the old world differed -mines, haciendas, and "encomiendas" characterized the new- the economic structure and relations of production could still be called feudal. Spain was feudal; its colonies should also be.4 These conclusions allow little room for regional originality and ignore the whole cultural and institutional innovation of the postcolonial context.

Arguments about globalization are, in many respects, similar to old arguments about modernization.5 Amartya Sen, for instance, has described the controversy about globalization in a way that is reminiscent of debates about modernity:

(...) those who take an upbeat view of globalization see it as marvelous contribution of Western civilization to the world (...) the great developments happened in Europe: first came the Renaissance, then the Enlightenment and the Industrial Revolution, and that lead to a massive increase in living standards in the West. And now the great achievements of the West are spreading to the World (...) From the opposite perspective Western dominance -sometimes seen as a continuation of Western imperialism- is the devil of the piece (...) The celebration of various non Western identities, defined as religion (...) region (...) or culture can add fuel to the fire of confrontation with the West.6

These views, as Sen also points out, are, of course, limited to specific historical periods and spaces. If one goes back ten centuries, one finds a different flow of globalization at work. Dissemination went from East to West, from China, India and the Middle East, to Europe. It was only after the eleventh century that the current paradigm emerged. Up until now it continues to be valid. Latin America, however, introduces important rectifications in terms of its timing, lines of causality, and contexts.

My point is that in both modernization and globalization theories, regardless of the inspiration, Latin America has been seen as "reacting" and "adjusting" to forces originating elsewhere. Leftists, liberals, and conservatives alike have coincided in viewing the region as the latest and most important trench against globalization. It has been said that in the "ongoing war of resistance" the region is one of the last important bastions, fighting globalization both from above and below. While these claims are not completely wrong, they are simplistic. They, among other things, have plainly ignored the contribution of Latin America to modernity and the expansion of what literature has usually called "the modern West"

What was that particular contribution?

1) An alternative to European and North American institutional models regarding the connection between the state and the nation. The "state" in Latin America tried to "make" the nation in its entirety, rather than the other way round. This particular connection has been, to my mind, mostly overlooked. A basic reason for this neglect is that, for the most part, literature on the formation of the nation-state in Latin America and elsewhere has focused on the state but ignored the nation part of this equation.

2) The implementation, from the onset of nation-state building, of the modern one state-one nation formula. Latin American nation-states emerged from a model that tried to attach an in-the-making nation to an in-themaking state. In other words, nation builders subscribed to, at the time, a popular modern notion: one nation to each state, and one state to each nation. That is, unlike the European and Asian experiences, each state was supposed to rule over one nation rather than over many. And, following the rise of modern nationalism in Europe, Latin America believed that each sovereign nation should be represented by its own state.

3) An innovative conception of the national community that tried to unite members by stressing an open -and uncertain- future as one of the most important factors in the conceptualization of the nation. This runs counter to what most literature on nation building and nationalism has stressed as a binding factor among members of the nation: the importance of the past, common history, and traditions.

As we shall see, in Latin America, the nation-state was structured under the guidelines of republicanism, which was quickly adopted by most of the region. In Europe, this model became dominant only after World War I. And it was only by the mid-twentieth century that we find it as a dominant model in Central Asia and Africa, at a time in which postcolonial states struggled to integrate different ethnicities, tribal rivalries, and religious differences into a modern unifying version of the nation and the state. Whether this was a better institutional choice or not for Latin America, or whether modernity is better than other political and social arrangements, is not my concern here. I want only to make the case that Latin America created its own modernity, and that this can be seen in the particular model of the nation state and republican rule that the region developed.

In the rest of this essay, I will succinctly make the case for Latin America as a modernizer rather than as a mere receptor of modernity. I will do so by, first, offering a brief comparative overview of nation-building in Latin America, Europe, and the United States. Second, I will try to summarily discuss the particular contribution of Latin America to a wider and global process of nation-making that spanned the eighteenth, nineteenth and early twentieth century.

Modernity and the Nation

Modernity includes more than economic development. It is also the creation of institutional modular arrangements that can be transferred and imported from one region in the global system to another. Industrialization and modern economic financial structures can be bettered and encouraged but they cannot be totally exported. Institutions can. Thus, the structural paradox of Latin America, pointed out long ago by dependency theorists like Cardoso and Faletto: modern institutions (parties, unions, party systems, nation-states) long endured and functioned with different degrees of autonomy but in less developed contexts.7

Very importantly, modernity is also about the creation and evolution of imaginaries. In this regard, Latin America represents one of those special intersections of the post-colonial where different images of power connected to the global and the local met, and where border thinking filtered different imageries of modernity. These images of modernity were strongly connected with ideas about the desired "national community", with a debate as to what should unite individuals and peoples under the same "nation", and with formulae as to how to create needed bonds between governments and citizens. What I want to stress here is that from around 1810 to the early 1900s, among other things, conceptualizations of the nation and its future, both desired and real, became crucial blocks in the construction of the nation-state.

Discussing modernity in connection to nation-building does not mean that one needs to adopt a Eurocentric or North American perspective.8 Indeed, Latin American modernity included subaltern views and cultures as much as it did racism, violence, and dualism.9 Traditional historiography has correctly stressed the importance of the possible options that faced the new elites in power after independence. Some of them were conducive to trying to imitate either Europe or the United States. The result was a mixture of Creole, indigenous, and foreign influences: "Hispanoamérica miró a sí misma y recuperó el modelo político hispano-criollo, de raíz medieval e igualitaria. Miró a Inglaterra y a Francia, cuyos regímenes políticos derivaban de sendas revoluciones (...) Y miró a Estados Unidos, el único caso en el que el movimiento democrático y republicano se había dado junto con un movimiento emancipador".10 These choices and their mixtures notwithstanding, toward the end of the nineteenth century most of the region had created its own version of modernity. Almost the entire region opted for republican rule and slowly but surely accepted party competition and elections, closer to the modern North American model than to any other, but not exactly identical. Those who did not, like Venezuela, after the fall of Juan Vicente Gomez nonetheless evolved into electoral politics and a more modern design of the state. Mexico and the Mexican revolution provide a well-known exception that confirms the rule.

State makers adopted a modern notion of legitimacy that differed from that of Europe and the United States. Nations were conceived and built at the post-colonial crossroads of cultures, global influences, modern liberal thinking, and colonial backgrounds of dependence, resistance, and negotiation. Images and conceptualizations of "the nation" were bound to incorporate bits and pieces of all this process and the imaginary of indigenous, ethnic and immigrant communities. While most literature agrees that subaltern notions of the nation survived at the margins of "official" definitions promoted by the state, in official conceptualizations and imagining of the nation much of the subaltern was also incorporated. Total exclusion was attempted but failed; in the end, those excluded nonetheless impinged some of their imaginary of modernity and the nation upon the "official" definitions of the national community promoted by the state.

Europe and Latin America

A comparative overview of Latin America and Europe supports the notion that the region made its own contributions to the expansion of modernity and "the West", rather than being a mere imitator of influences coming from elsewhere. In Asia, the Middle East, and Europe, "nations", in the traditional sense of the word, possessed long and rich histories. Long before the modernizing sixteenth century, they constituted part of the European landscape. Most of them lived, for centuries, under the ruling of the same state, e.g., empires, protectorates, or kingdoms. As Charles Tilly and others argued many times, the advent of the modern world marked a shift toward the emergence of smaller states. Such states tended to rule over fewer nations. The one state-one nation formula, however, remained more the exception than the rule for a long time. Latin America adopted this model shortly after independence and established its preeminence in a whole region before Europe did likewise. Europeans for sure did not see modernity in Latin America. And as far as North Americans were concerned, the region remained a mix of barbarism and republicanism. Yet, looked at from the point of view of comparative political analysis and bearing in mind other less developed regions of the world, Latin America represented much more than that. It represented another model of modernity.

True, the new states were, by European standards, weak.11 Such weakness, however, did not make their agendas less modern. The encouragement of patriotism and the construction of national identity, for instance, appeared as top priorities in the agenda of the new republican states. No question that pre-modern states (like the Elizabethan state, for instance) behaved similarly to modern states in a number of counts. For instance, they made strong efforts to "consolidate patriotic feeling".12 Since the late seventeenth century European states resorted to all means at their disposal to inculcate strong patriotism and nationalism, waging "patriotic" wars on one another.13 At first sight, one seems to find something similar in nineteenth century Latin America. A closer look, however, detects something qualitatively different.

Pre-modern states did not prioritize the creation of consensus about the "national character" or the characteristics of the nation upon which they were to rule. Contrastingly, Latin American state makers took these matters very seriously. States in Latin America also showed interest in encouraging patriotism, but at the same time they worried about achieving consensus regarding the cultural and physical characteristics of the national community. The development of the nation-state paralleled an emphasis on patriotism and nationalism. It also worked at post-colonial definitions and imaginings of the "national community". And the new states definitely strived much more thoroughly to implement the modern one nation-one state formula.

In Europe, older, pre-modern and stronger states could traditionally rule over many nations. These nations were many indeed.

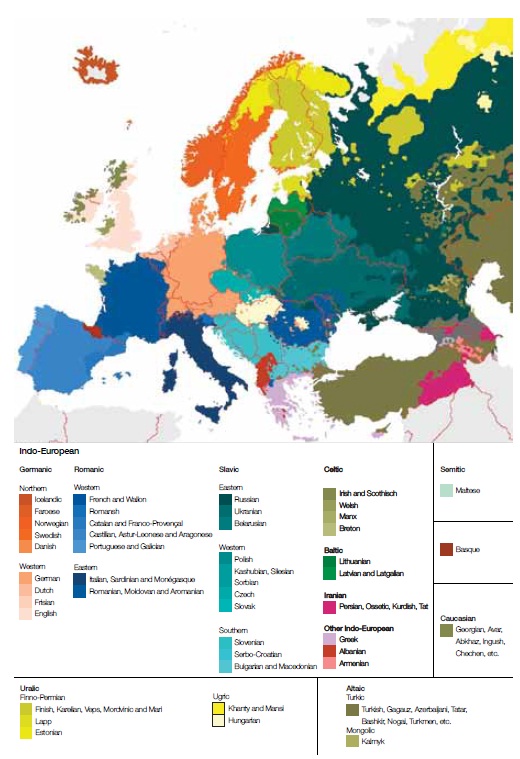

FIGURE 1. Location and character of different ethnicities and nationalities in Europe in 1900.

Perry Castaneda, Library Map Collection, University of Texas, Austin.

Available in http://www.lib.utexas.edu/maps/map_sites/hist_sites.html

The ratio between these nations and existing states was heavy on the side of nations. That is, few states were able to rule over many nations. Nations were bounded by shared ethnicities, culture, common histories, and geographical location. Armies, taxation systems, and bureaucracies bound states. Nations epitomized strong political and social actors that were able to survive amalgamation into empires and large states. In nineteenth century Europe, size was part of the definition of a nation. It was argued that small nations had much to gain by merging into bigger ones. Strong states embodied the conduit by which these mergers could take place. Multiethnic and multiracial nations became, therefore, unavoidable. The nation/state had to become, by force, nationally heterogeneous. Europe, diverse and rich in nationalities (figure 1), had no choice but to form multinational nations. Otherwise, it would evolve into what was perceived as a hopeless "small nation model", that is, a continent defined by nations of Lithuanians, Moldavians, Basques, etc. Large territories and abundant populations provided the clue for the success of a large and strong "Nation" actually composed of many smaller "nations" under the administration of one well-built state.

In Latin America, the "strong nation" model was also popular. Yet nation makers relied on weaker institutions, and thus, a unified nation where multiethnic and racial differences could be avoided or eliminated altogether seemed to be a more viable model. From their standpoint, in addition to racism and prejudice, the survival of indigenous nations triggered fear. The idea of many nations living under one state was perceived as a recipe for conflict. They saw strength in homogeneity rather than in heterogeneity. In the imaginary of modernity, conflict among nations was the source of much evil and ought to be avoided. Indeed, for some, it was up to modernity to eliminate nations altogether. The reasons were obvious: many contemporaries looked at strong national feeling as one of the most important causes of war.14 So, weak Latin American states feared the eruption of internal wars caused by conflict among nations and sought to avoid it.

Thus, for the most part, Latin American states were able to block Native American nations from having political representation in the new states. Indeed, with different degrees of success, they tried to avoid the one state-many nations situation at all costs. On the one hand, Liberalism fostered the combination of Republican rule with the one state-one nation formulae; this was taken seriously. On the other, modernity's prescription -to each state its own nation, to each nation its own state- seemed more convenient for weaker states, such as the republics of Latin America. It represented a more manageable system: one in which new rulers could centralize power and construct legitimacy by relying upon one dominant national identity. Similarly to what occurred in Europe, however, and despite all the killings, slavery, and elimination of Native Americans, in Latin America multiethnic and multiracial "Nations" could not be completely avoided. With the (very relative) exception of a few lands of recent settlement (Argentina, Uruguay, Costa Rica) whose cities were populated by a majority of Europeans, the rest of the region had to accommodate large numbers of people representing different cultures, races, and ethnicities.

Lord Acton once argued that nations became stronger when possessing different centers of power represented by different nationalities and cultures: "A state which is incompetent to satisfy different races condemns itself; a state which labors to neutralize, to absorb or expel them, destroys it own vitality; a state who does not include them is destitute of the chief basis of self-government."15 His argument did not take roots in Latin America. Only slowly did the Latin American nation state acknowledge diversity. When in the twentieth century it did so, it perceived it as something that needed to be integrated into a larger and stronger "national culture". This explains the policies that states designed from the onset to reduce the influence and physical presence of undesired groups (African Americans, Indigenous populations) by marginalization and extermination. We know that immigration policy was used to "purify" the population as well. As has been amply documented, the Argentinean, Uruguayan, Peruvian, and Brazilian states aggressively encouraged immigration of the desired "races". At many points in its development- Colombia tried to do the same. One can argue that all these tensions were associated with the imposition of a modern model of nation making. A modern landscape of nation-states did emerge in the region. Most of them instituted policies aimed at creating their desired nation.

Figure 2 pictures the very early rise (1830) of a number of nation-states in Latin America, some of them already republics. A few of the new states are still missing in this picture, which represents post-colonial Latin America right after independence. As has often been said, this political map has experienced only a few alterations to the present day. Colonial possessions notwithstanding, the picture is quite similar to that of the twentieth century.

FIGURE 2.

South America in 1830.Perry Castaneda, Library Map Collection, University of Texas, Austin.

Available in http://www.lib.utexas.edu/maps/map_sites/hist_sites.html

Therefore, Europe and Latin America can be said to represent very different and yet complementary processes of nation-state formation and modernity, both belonging to the West. Europe was definitely more "modern" in terms of economic development, patterns of centralization of authority, organization of bureaucracies, educational systems, and the development of science and technology. Latin America represented a modern, yet different experience in terms of the emergence of nation-states at an earlier time in conjunction with globalization, and the development of polities that, from scratch, accepted the notion that the state could craft the characteristics of a unifying nation.

None of the Latin American republics seriously thought of reproducing European models of rule. Europe was mentioned, dreamed, imagined, fantasized, criticized, and many times praised. At the same time, there existed a solid awareness that it could not really be "copied". The U.S. did offer useful examples in terms of concrete policies of immigration, agricultural development, constitutional amendments, etc. But nobody really seriously considered that the United States could be reproduced down south either. We should not forget either that, in the eyes of Latin American republics, most of Europe did not just represent modernity: it also embodied monarchical rule, colonialism, and archaic institutions. Regarding the United States, most Latin American nation makers viewed the First Republic as a model worth imitating; President Faustino Sarmiento in Argentina has been often cited as a well-known example of admiration for the u.s. model of nation building. Yet, as we shall see, the United States was also perceived as too different a republican experience from that of Latin America, with its emphasis on religious communitarian values, land grant policies, a code of communal laws inherited from the Tudors, and a Federal system that at mid-nineteenth century seemed too difficult to reproduce in different Latin American regions.

The Incorporation of "the Masses" on Both Sides of the Atlantic

Both the Old and New Worlds confronted the task of "accommodating the masses" into politics and creating identity. Since the eighteenth century "the nation" that elites and government tried to construct was designed, in part, to keep the masses at bay. But in the end the "masses" had to be integrated. In the late 1920s Ortega y Gasset argued that modernity made "the people" believe that it was sovereign: "To this day, the ideal has been changed into a reality, not only in legislation (...) but in the heart of every individual (...) To my mind, anyone who does not realize this curious situation of the masses, can understand nothing of what today is beginning to happen in the world."16 In heterogeneous new societies like those of Latin America -as was also the case in the United States, Australia, and Canada- the construction of national identity was forced to deal, from the onset, with the aspirations of "the masses". State formation was shaped by pressures to accommodate the masses into a republican model of power centralization. This had advantages and disadvantages.

European states, bearers of long established traditions, seemed less free to innovate than the new republics. Rulers in Latin America, in a vacuum of established glorious traditions that would fit the new republics, appeared freer to innovate. The result was that they mixed a number of colonial practices with liberal republican institutions of government and a number of foreign influences, both from outside (from the international system) and from inside the nation (immigrants). Yet this freedom to innovate and choose from possible types of regimes remained more limiting in Latin America than in Europe. European states, stronger and possessing well-established traditions that glorified rulers, political institutions, and national histories could resort to past glories and heroes and thus opt from a wider arrange of possible models of government. Even as late as the nineteenth century the return of monarchy, empire, colonialism, and other forms of traditional aristocratic rule remained a possibility and a reality (France, Austria, Germany, Italy, etc). After the 1850s, liberal and socialist doctrines were popular in intellectual and political thinking as well, and many in Europe feared that the advent of the masses into politics would bring about a sort of wild socialism or communism able to undermine the status quo.

In Latin America, practically the opposite was true. To the question of modern democracy, republican rule, monarchy, socialism, or imperialism, the region had but one answer: modern liberal republics. Mexico of course debated it, and similar controversies can be found across the region. And yet, again, shortly after independence most countries adopted republican rule and constitutional regimes. In a way, Francis Fukuyama's argument of "the end of history" could apply here. Most ruling elites considered that republican rule and some sort of participatory political system was their only available alternative. Of course pro-colonial and monarchical factions did emerge in Latin America. But, unlike those in Europe, they did not possess the power to establish monarchical regimes. Rather, in most of the continent the new ruling elites claimed to exercise power in the name of change and newness, rather than in the name of "pre-modern forms of rule". In terms of monarchical and imperial rule, there surely existed honorable indigenous precedents. But when General San Martin argued that perhaps the best thing for the new emerging polities was to rescue a Latin American royal tradition (as opposed to borrowing it from Europe) and thus to elect an Inca Emperor as a supreme ruler, his proposal provoked utter rejection.17 Not surprisingly, in a postcolonial context, Europeans were considered a superior race and the adoption of an Inca Dynasty, as a source of royal legitimacy seemed utterly unacceptable. As the assembly put it, to revert to an "inferior Indian royal house" was deemed backwards and against modernity.

Another aspect of the process of incorporation of the "masses" into the nation-state that differentiated Europe from Latin America -and which points to Latin American modernity- was the type of incorporation. On both shores of the Atlantic, elites and the emerging middle classes shared a number of concerns about the ascent of the populace as an actor in the process of decision-making. In Europe, many believed that the mob was taking over the politics of their time.18 During the early 1900s the same feeling spread through Latin America. Similarly to the current situation, in Europe, at the time, it was believed that the "ghosts" of "the crowd" and "the "masses" represented a serious threat to European culture.19 Somewhat similarly, in the new republics of Latin America, elites felt besieged by indigenous peoples, Africans, and the urban and rural poor. Progressives and liberals on both sides of the Atlantic saw it differently: the masses represented the glorious armies of proletarians and peasants defending self-determination and progress. Thus, urban crowds seemed to symbolize, at the same time, the most dangerous manifestations of modern life and a source of promise and inspiration.

These crowds were present in Argentina, Uruguay, Chile, Peru, Mexico, and Colombia. In the region as a whole, weak states faced demands from below. The rank and file of political parties, guerrilla-type groups, and dissident regional leaders could often threaten the state. In Europe, these threats were not as powerful. Thus, in Latin America demands coming from local caudillos and the lower classes, as well as the evolving pacts between the central power and rebellious forces were incorporated into the institutions of the state and the conceptualization of the nation.20 Unlike Europe, this characterized the formation of the modern republican state from the beginning. Therefore, the institutional vehicle of incorporation (stronger monarchies and larger states in Europe, weak republics in Latin America) separated the two worlds.

In some regions of Latin America like the River Plate, where indigenous populations were less numerous, prior identities were weakened either by war, displacement, or genocide. In Colombia, we find a similar situation in many ways. Unlike Europe, elites had to create a new sense of belonging. In heterogeneous societies whose inhabitants remained deeply divided along racial, ethnic, and class lines, and where large contingents of immigrants kept their allegiance to foreign nationalities, elites needed to create some sort of national identity to build legitimacy. Here, Europe also experienced something different, not because states did not house immigrants from distant regions of the continent, but because of much smaller sheer numbers.

Europe and Latin America shared a similar conceptualization of the nation in that "the nation" was conceived as representing a defined hierarchy. In Latin America, horizontal camaraderie, as defined especially by Benedict Anderson, was hardly a part of the imagining of the national community. The nation was going to be status and class- oriented. In both Latin America and North America, race remained an unresolved issue from the beginning. In Europe, ethnicity, religion, and race also represented obstacles to integration into a "nation". In both Europe and Latin America, the "emotional attachment" that united people to their nations depended upon race, ethnicity, status, and class. Europe differed from Latin America on this score, since in Latin America those who were disenfranchised by race and ethnicity constituted the majority of the population in most of the region.

As has often been remarked, another very important difference with the European scene was that by the 1890s and beyond, Latin American nations were, for the most part, not strong enough to wage war on neighbors. Therefore, these nations were described, perceived, and imagined in different ways from those in which Europeans defined theirs. As in Europe, many members of the ruling elites of Brazil, Argentina, Peru, Venezuela or Mexico envisioned some kind of colonial expansion. In their own eyes and also in the perception of Europeans, this would have elevated the status of their nations. In practice, however, Latin American states remained unable to expand by war and conquest.21

Both in Europe and Latin America nationalism was perceived as a growing problem. Because in Argentina and Uruguay, for instance, most urban dwellers were foreigners or first-generation creoles, the new republican states perceived the upsurge of European nationalism as directly affecting their urban masses. They worried about Italian immigrants who wanted to remain Italian rather than adopting the Argentine or Uruguayan nationalities, Spaniards who wanted to remain Spaniards, Polish who wanted to remain Polish, and Middle Eastern immigrants who kept allegiance to Syria, Armenia, or Turkey. In other Latin American countries with less urbanization or fewer immigrant populations, the masses of "backward" Native Americans, the rural poor, and dispossessed peasants who, by the end of the century had started to migrate to the capital cities, also inspired awe and fear in the eyes of the ruling coalitions. They were perceived, as in Peru, Bolivia, Mexico, or Ecuador, as challengers of the desired equation of one nation-one government. In Europe we can find similar scenarios: in Italy, for instance, backward peasants from the south who joined the more advanced North provoked fears of secession and revolution.22 Yet, Europe, with modern states in place and national armies fully developed, could more comfortably absorb or repress diversity and dissidence than Latin America.

Latin American Modernity

Since the mid-nineteenth century, a negative image of the region was installed both in the European and Latin American imaginaries. These images, based on some hard facts, placed Latin America far away from modernity. Insecurity and war were major concerns. In Mexico, "Esta pestilencia de los ladrones que infesta a la República nunca ha podido ser extirpada (...) con el pretexto de expulsar a los españoles esas partidas armadas invaden los caminos entre Veracruz y la capital (...) arruinando el comercio y haciendo caso omiso de la opinión pública y la ley de 1824 (...)"23 While banditry in Mexico has been considered to be the most widespread and resilient, in the rest of the region the rural poor and landless peasants also made their way, as they could, into banditry to escape authority and prior exploitation; this process lingered until the beginning of the 20th Century. Bandits in Colombia, as has been documented, became an integral part of the political landscape.24

In 1865, ont the other end of the continent, the Spanish Consul in Montevideo also reported that chaos and insecurity reigned in the River Plate and beyond. "Since their foundation (the Consul argued) (...) these counties have been at war and have enjoyed only brief peace (all of which) provokes in all the social classes mistrust and apathy, and in all sectors of the economy, commercial stagnation."25 The Consul was not alone. Others, however, blamed the backwardness of Latin America precisely on the heritage of the country he represented. Looking at Paraguay in the late 1890s, for instance, a North American reporter concluded that only foreign influence from other European countries -rather than Spain- could make a difference: "Whatever material advance this country may make in the future, will be mainly due to foreigners who are rapidly crowding in. The ubiquitous gentlemen from the north of Italy is already present in relatively large numbers, and the enterprising German is becoming alive to the good pastures of the Rio Alpa (...) The Paraguayan is an indolent being whose needs are simple and easily supplied." Yet Spanish culture, in fact, seemed to be even more damaging than indigenous traditions and values: "Crime is comparatively rare in Paraguay, and the majority of the bad Guaraníes are to be found in the Argentine, with the evil characteristics of the sixteenth century Spaniard and his composition."26

Overpopulated public bureaucracies were, for many observers, another endemic problem of the new republics. In 1891, looking at Argentina in the midst of its economic bonanza, a British journalist reflected on the negative consequences of having too large a public sector: "(...) it is interesting to glance at the number of employees attached to the National Government (...) salaries and wages are 30% of the national revenue (...) staring to us in the face is evident that the provinces, with the exception of Entre Rios, cannot hope to meet their liabilities under the system of administration now in force (...) in Buenos Ayres (...) the revenue in 1882 was $12.805.336 (...) of which 49% went to pay salaries and wages."27

What such images hide is that modernity is not only about order but most times also about chaos, war, conflict, unsettled politics, and lawlessness. They also dismissed the institutional and cultural novelty of the new societies. Lack of information, the strong influence of Anglo-American literature and the frustration of Latin American intellectuals with the backwardness of their countries, has fogged this picture. Not to mention the strongly rooted assumption that the colonial era negatively conditioned the capacity of the region to achieve high levels of development and social justice. In Local Histories, Global Designs, Walter Mignolo has argued that the most important reason for this neglect lies with historical Anglo/French literature.28 I would add that modernization, world-system, dependency, and international relations theories have made a huge contribution in this direction as well. The record of the region in terms of traditional indicators of modernity and development continues to be discouraging, even today. Yet this does not mean that the region could not create a modernity of its own that added to Western modernity in general. During the "first wave of globalization", circa 1870-1920, a crucial time in the global proliferation of modernization and liberalism, regions of Latin America represented avant-garde modernity.

Nations and Futures

Nation building in Latin America offers a correction to the existing (and huge) available literature on national identity, the nation-state, and the nation.29 This literature has emphasized history and past collective experiences as the binding element that creates a sense of belonging and thus constructs what Max Weber defined as a "community of sentiment". In Latin America, however, history was weak, the past controversial, and sentiments of unity frail. Instead, ideas about the future of the nation seemed to provide a promising way to create identity. Unlike what happened in Europe, the nation could not be solely constructed upon a glorious past. The intelligentsia and public figures, including politicians, struggled to create such a past. The result was a heated debate about the convenience of enhancing the indigenous, Spanish, Portuguese and colonial past of Latin America. A fresh, new start seemed more promising. And yet, the new Creole elite did not wholly agree as to the characteristics of this "new start". One thing was clear: across the region Spanish and indigenous cultures were thought not to provide the desire foundations for the modern nation. Founding fathers became almost as important as in the u.s. and yet the strong rivalry that separated them and the almost permanent state of war of the nineteenth century made it difficult to built national identity exclusively upon their shoulders.

Benedict Anderson writes that by the mid-nineteenth century "a model of the independent nation-state was available for pirating" and that this model was crafted in Latin America.30 This is correct. Yet this model included more than a reinterpretation of history and tradition. The conceptualization and construction of one of the factors of that equation, the nation, contained an equally important ingredient: an imagery of the future of the nation. States, intellectuals, the educational system, and politicians promoted images of its future in order to encourage identity and belonging.

Across the region, rulers talked about a "proyecto nacional" or a "proyecto de nacion"; implicit in this idea was speculation about its future. As James Scott has claimed, states are, among other things, planners, and this involves specific notions of temporality, time, and space.31 His point is well taken: social engineering and systems of power distribution usually include images of what the future society would look like. The state "sees" the world in a particular way (as a state) creating a vision that obviously includes the future. Latin American republican states exercised this vision quite strongly.32 They envisioned the future of the national community in different ways according to contexts. They coincided, however, in the adoption of one model crafted upon liberal ideology: the combination of republicanism with the one state /one nation formulae.33

Independence was, of course, a political event and cannot be equated with nation-building or with the actual existence of a nation. That took a longer time. Mexico has provoked one of the richest debates about the timing of nation building. Some have argued that at independence only the elites talked about the nation while the popular sectors knew little about its meaning or existence.34 Others, such as Florescano, suggested that independence provided the opportunity for the unfolding of the idea of nation; it had existed but only in an embryonic stage in the colonial period. Lorenzo Meyer, on his part, has claimed that until the 1870s there was neither state nor nation in Mexico; this parallels similar arguments made about Argentina, Uruguay, Colombia, Peru, and Bolivia. Alan Knight has distinguished between cultural nationalism, on the one hand, and nation building, on the other, an argument that, in different words, has also been made about Argentina and Uruguay. Timothy Anna has beautifully captured this debate in Mexico.35

I find it significant that one can also find similar debates regarding the connection between nation and state elsewhere in the region. Anna is right in suggesting that the nation possesses an institutional component. Many others are also right to say that nationalism is political, ideological, and cultural. Yet the conceptualization and definition of the nation is different from nationalism and goes beyond institutions. The nation, to exist, needs to be somehow conceptualized, defined, and, imagined. Anderson stresses imagination, I stress conceptualization. Conceptualizing the nation includes not only symbolisms about the past but also of the future.

In sum, the Latin American nation-state was, to a large extent, constructed upon the modern notion that the future of the national community is part of the definition of the nation. What does this mean as an analytical category? It can take many forms. It can refer to fate, predetermination, or religious mission as it did, for the most part, in the U. S. It can also include opaque prospects, damning the nation from its beginnings, as we know from Ancient Greece. It can also be based upon the "special" qualities of its people, as it has been said of England or France.36 Or it can reflect extreme confidence in the "potential" of a given nation (human community) to achieve prosperity. Latin America contributed something different. Like the u.s., the region adopted Federalism as a basic political organization. Unlike the u.s., however, elites and government favored the "open-ended outcome" meaning of the word future rather than notions of destiny or fate.37

"Destiny" sounded 1) too religious for most of the new republics that had been born ravaged by secular and religious struggles; 2) too Spanish; 3) too connected to a past that elites wanted to redefine, and, especially, 4) too demanding. Destinies require definitions and compromise and usually build upon known traditions. In the region, elites found compromises threatening and traditions very controversial to define.

Deprived of a sense of mission or destiny, the future of the nation included a heavy dose of uncertainty. This is counterintuitive because we could assume that ideas about the future should be used to guarantee stability and encourage membership in the nation. Uncertainty seems to encourage the opposite. If one defines the nation as a community of horizontal solidarity, as Benedict Anderson does, uncertainty would diminish simply because members would be more prone to help each other as equal parts of the community and to collaborate for the common good. But the nation in Latin America was conceived hierarchically, rather than as a community of equals.38 Thus, while most elites manifested that the future looked bright, uncertainty was also ingrained into the very definition of the nation. From the standpoint of government, the good news was that they did not necessarily have to take the entire blame when things went wrong. A tradition was forged by which authorities often charged the international market, the influence of powerful countries, and international pressures for the misfortunes of the nation.

Ethnicity, culture, and language are known factors that have contributed to identity. In the strong heterogeneity of Latin America none of these factors could have become the needed glue to construct identity. The future of the nation, however, provided a possible solution for the elites: all "races", cultures, and ethnicities -including immigrants- could feel similarly about the promise of a future that could be prosperous. The problem that elites and the state faced was to make the instrumentation of this conception of the nation possible, and to convince those who belonged to the "undesired" ethnicities and the poor in general that their "nation" would embrace them. This was not an easy task.

Indeed, in many cases, the future of the nation predicted the eventual disappearance of unwanted ethnicities. The state took a leading role in the carving of the elites' desired future for the nation, and, therefore, in the weakening of these undesired groups. It either looked the other way when local landholders or notables systematically marginalized or tried to eliminate them or, as in Peru and Argentina, the state instrumented military campaigns to weaken indigenous communities and eliminate possible alternative conceptions of "the nation". Or as in twentieth century Mexico, it created encompassing categories such as "mestizo",39 in order to try to blend a variety of cultures and ethnicities into one that would represent the "Mexican Nation". In most cases, the Latin American states emerging in the nineteenth century favored the ideal of a more European/White nation encouraging miscegenation and/or the importing of immigrants from the desired "races" (Colombia, Peru, Argentina, Uruguay, Chile, Bolivia). Thus, the state took upon itself the construction of a nation, one nation, where ethnicities were supposed to fuse into a unifying entity. An emphasis on the future of the nation as a unifying factor, rather than a tradition created on a glorious past, seemed more appealing and useful to achieve these goals. Another republican experiment, the United States, also placed a strong emphasis on the future of the nation to both achieve unity and define the new nation. Yet it did so in a different way that differentiated North American modernity from that of Latin America.

Two Paths to a Modern Nation: Latin America and the United States

In 1776, Thomas Paine exulted: "We have it in our power to begin the world over again". After the French Revolution, he believed that France, too, had started a new era for the whole of humanity. He believed he had seen "government begin, as if we have lived at the beginning of time".40 Hegel paid tribute to the United States of America by saying that it was a world historical phenomenon and that it represented "(...) the land of the future where, in the ages that lie before us, the burden of the World's History shall reveal itself".41 The country itself was predicated upon the notion that the American nation represented a future of open possibilities and hope. In a different way, this modern conceptualization of the nation, as defined more by its future than by its past, was also present in the Latin American republics.

In the United States, the awareness of having "founded" the first viable republic of modern times contributed to constructing a sense of national identity tied more to the future than to the past. One finds a similar situation in Latin America, although these republics no doubt knew that they were not the first and that the United States had walked a route that was not totally open for them. In Argentina, Uruguay and, to a great extent, Colombia, Venezuela, Chile, and Costa Rica, the state created definitions of "the nation" in which the openness of the future paralleled those that inspired the definition of the American nation. In both Americas, modern notions of the nation emerged that emphasized more the future than the past. In other words, in both Americas, members imagined and conceptualized their nations through its future rather than its past. One can argue that this is the main modern novelty associated to the construction of the nation in the Americas.

Some of the major differences between the United States and Latin America point to dissimilar expressions of modernity rather than to a "real" modern u.s. process of nation-building that would contrast with a pre-modern process of nation-building in underdeveloped Latin America.

Modernity has been traditionally tied to the notion of "progress". When defining "progress", Sidney Pollard wrote that it was "the assumption than a pattern of change exists in the history of mankind (...) that consists in irreversible changes in one direction only, and that this direction is toward improvement".42 As Pollard points out, material progress is a relatively recent notion of the last three hundred years or so, while moral progress, a concern of earlier times, has been mostly assumed to go along with the material. This depicts Latin American modernity and contributes to finding useful contrasts with the earlier modernization of the first republic.

Material progress -framed by science, industry, and a profitable export economy- was in the minds of Latin American nation-makers. They thought that moral progress would follow. Unlike the u.s., no particular religious belief or eschatology was attached to this nineteenth century notion of progress as it made its way into the conceptualization of the nation. For Latin Americans, virtue, the will and capacity to put the public interest over the private, represented indeed a sign of civilization and modernity. Had not the Greeks spoken of political virtue and related it to the right polity? Did not Plato think of republics as the embodiment of virtue? Yet most nation-builders, first and foremost, regarded the material basis of progress as the key prerequisite for modernity and, hopefully, a more virtuous polity.

When these desired goals did not materialize, as was often the case, ruling elites and the emerging middle sectors blamed scarce manufacturing, international markets, fraud, dependence, and the inefficiency of the agrarian sector for these failures. Scholars and public figures often argued that lack of economic progress hindered virtue, weakened institutions, and encouraged corruption, rather than the other way round. Here and there morals and values were mentioned as weak foundations and the cause of all evils. But most contemporaries focused on economics.

We find something quite different in the United States, where "the politics of liberty" were associated much more with virtue than with economic development. Jefferson was adamant that manufacturing would be restricted because it generates much "subservience and venality, suffocates the germ of virtue, and prepares fit tools for the designs of ambition". Agriculture, contrastingly, was a generator of virtue.43 Modernity could represent both good and evil. He took an extreme position, but he was not alone. The American Revolution was a revolution about liberty -rather than about freedom- and it was framed by the politics of virtue. In fact, it was because the founders -especially in the Federalist Papers- thought that virtue was insufficient to maintain liberty that politics became necessary. The role of institutions was to provide a corrective to possible deviations from virtue. Left to their own impulses and affairs, men would very likely move away from virtue.

Following Montesquieu, the anti-Federalists stressed the size of the community and believed that virtuous people could live only in a republic that was small, predominantly agrarian, and homogeneous. Madison disagreed. He thought that a republic could be sustained in a larger territory. In this debate, the Federalists prevailed. Their thinking was that a larger republic could also achieve moral sustainability. The Federalists argued that the state was to encourage commerce and enlarge the republic fostering a "multiplicity" and "diversity" of interests together with the parties representing such interests. Echoing Hume and Adam Smith, -but unlike Jefferson- the Federalists looked upon an expansive economy as the condition for moral self-betterment. Yet, in the matter of virtue and ethics, they also took Montesquieu to heart, and crafted their conception of the American nation upon ethical principles.

This was not naïve. They felt that the role of republican institutions was to ensure that liberty and virtue prevailed. Men were not to be trusted to spontaneously sustain the kind of needed virtue to run a healthy nation; thus, institutions were needed to prevent corruption and preserve the future of the Union.

This conveys a different version of the role of institutions from the one that more than a century later will dominate Latin America. Institutions seemed to play a similar role in both, but in Latin America, religion, institutions, and liberty, did not participate equally in the conceptualization of the nation. In the United States, they did. One could claim that this eighteenth century North American notion of modernity and the nation was less "modern" than the Latin American ones that prevailed later on in the nineteenth. Was North American modernity anti-capitalist? Neither of these assumptions would be true. In the United States, virtue, religion, and material development were seen as complementary sides of modernity. This was an implicit assumption that did not get written in the Constitution. As in Latin America, neither virtue nor religion was mentioned in the founding Constitutional document. As opposed to Latin America, however, religion, the real philosophical foundation of virtue, in tandem with liberty, constituted the basic ingredients of the American nation and its future development.

In the United States, the role of the state was different. Government was there only to promote and guarantee liberty, since the "American nation" was believed to have pre-existed the state.44 In Latin America, contrastingly, the nation was conceived as a secular product. In the United States, religion and virtue did not constitute the objects of government because they would spontaneously emerge from the "natural impulses" of society. Society was, after all, the infrastructure of government. In Latin America, these impulses were not considered "natural" and the state needed to have a role in shaping them.

Indeed, the strong liberal/clerical cleavage that characterized the conceptualization of the nation and state-building in Latin America did not make much sense in the u.s. Religion in the United States did not need to be in the Constitution because it was believed to be firmly embedded in society. Religion in Latin America did not need to be in the Constitutions because the government's role was to keep Church and state separate. When religion was mentioned, it was precisely to make that point. Latin America comes closer to the French tradition that saw the role of religion very differently and thus conceived "the nation" and its future in very different way.

When writing about America half a century after the establishment of the first Republic, Tocqueville, from a French perspective, offered an analysis that facilitates comparison with the Latin American republics. The French philosophers, he wrote, thought "religious zeal ...will be extinguished as freedom and enlightenment increase". The United States disproved that theory. What surprised Tocqueville was that "among us (he meant the French) I had seen the spirit of religion and the spirit of freedom almost always moved in contrary directions. Here I found them united with one another; they reigned together in the same soil."45 Definitely, Latin America came closer to France than to the u.s. And yet it was different from France in that its construction of the nation, as in the United States, stressed more a projection into the future than into the past.

In sum, what were the major differences between the u.s. and Latin America in terms of how they conceived the future of the nation? First, the fact that nation in Latin America was conceived as a secular modern construct had implications for the way in which Latin Americans conceived of its future. In the u.s., notions of the end of history were associated, in part, with the conceptualization of the nation, and this sharply differentiated the two Americas.46 From the standpoint of civil religion, many of those who began the so-called "American experiment" conceived of it as an eschatological society, almost as a realized utopia.47 It is worth quoting Bellah at this point: "An axial critique of the fundamental premises of American society and culture would require not only a critique of ... individualism and its strange complementarity with the confusion of God and nation, but a critique of the Protestant Reformation itself, at least its most influential American forms. Such critique would show that the United States is not the City of God that it claims to be...The great Protestant mistake -into which Catholics have at times fallen- was to confuse religion and nation, to imagine that America had become a realized eschatology. Our participation in the great wars of the twentieth century only confirmed our sense of ourselves as beyond history, uniquely chosen in the world to defend the children of light against the children of darkness."48

Second, and as a consequence of this strong religious influence, u.s. citizens, for centuries, believed they were special and different, chosen by God to play a redemptive and unique role in the world.49 In its more exaggerated versions, nation-building combined with eschatology to produce a distinct mixture that included a strong faith in a possible rupture, not to mention the countdown to Christ's return to the chosen land.50 These notions are alien to the imagining of the Latin American nation.

Third, the relation between the state and the nation was different in these two waves of republicanism.51

Fourth, in Latin America, the notion of "a national future" in connection with the definition of the nation was conceived in terms of open possibilities. From the beginning, a sense of uncertainty formed part of the Latin American imagery of the future. This therefore opened the door for possible negative outcomes that became ingrained in the definition of the nation. In the United States we find a very different situation.

Fifth, these differences about how the future of the nation was conceived connect with different degrees of perceived exceptionality and the acceptance of foreign influences. It has often been pointed out that an "essential" part of American national identity is to believe that the u.s. stands as an exception and a unique social and political experiment. The United States, it has been argued, "is based on difference, on a tendency to define America as distinct from, even separate from, all that is foreign (...)."52 Republicanism and Protestantism were regarded as major features of this distinctiveness and uniqueness. This went hand in hand with a rejection of "all that was foreign". Thus, Washington's warning about "entangling alliances" with foreign powers that could jeopardize, among other things, the new Republic's destiny and mission.

Nothing can be more different from the foundations upon which Latin American republics created their conceptions of what was "national". In a situation of neocolonialism, state-makers and the intelligentsia also tried to guard the country from dangerous foreign influence. Nevertheless, under very strong global pressures the new republics were encouraged to search for mirrors and foreign inspiration. As a result, they ended up looking more outwards than inwards, embracing foreign ways and cultures.

Immigrant communities added to these influences. The rejection of Spanish traditions after the wars of independence was traumatizing. It pressed intellectuals and governments to look elsewhere, to indigenous traditions but even more so to North America and Europe. Even in Brazil, which did not experience a struggle for independence and acquired it under the watch of a Prince, the search for identity also meant a turn toward Europe in general rather than exclusively to Portugal. Brazilian intellectuals of the nineteenth century looked to France for philosophical guidance and to England for models of parliamentary government. Germany was expected to contribute metaphysics and technology. In Argentina, the same was true.53

Finally, what about the sense of manifest destiny that formed such an important part of the definition of the nation in the United States? Was it also present in Latin America? Argentina and Uruguay and to an extent other countries such as Peru, Bolivia, Mexico, and Colombia shared a very mild sense of manifest destiny in their unshakable faith in their natural resources and a future of prosperity. Brazilians definitely thought that their nation had a bright and promising future. However, Latin American nation-building fell quite short of a sense of manifest destiny. On an international scale of the use of manifest destinies in terms of the definition of the nation, Argentina and much of Latin America would lie at one extreme of the spectrum. The United States would follow in a sort of middle position. On the other extreme of the spectrum one could find, for instance, Germany, which at certain times in its history, spoke often of the grandeur of the German people and its destiny to dominate Europe and the world.

One can argue that in their quest for modernity, nineteenth century Latin American republics knew that their nations were in turmoil but in a lot of ways they also saw them as privileged and deserving of a bright future. Elites, intellectuals, and the state assigned a sort of independent entity status to the nation. They felt that the nation needed to be in permanent alert; otherwise, men could lead it into the wrong direction, especially public officials and institutions. Strong disagreement as to the historical foundations of the desired nation opened the door for serious considerations of its present and its future. Spain could not provide an adequate foundation. Here is another difference with the United States. In the North American Republic, the institutions and morals of the ex-colonizer were accepted as part of the new nation. In the America of the future that John Adams described as an "empire of liberty" comprising "twenty of thirty million of freemen without one noble or one king among them", Tudor Law remained strong and accepted, as well as British philosophy and commercial culture. Indeed, the British idea that the public good rested on social virtues became ingrained into the imagining of the American nation. One can argue that the United States experienced a process closer to introspection than to an outward-looking conception of the nation.

Conclusions

I have tried to show the nuances and characteristics of modernity in a post-colonial context in the hope of contributing to our understanding of modernity. For too long, modernity has been exclusively conceived as the creation and product of the advanced capitalist nations. We have shown that the conception and practice of nation-building, the nation state, and national identity do not actually fit that definition. Modernity, in the complex context of postcolonial Latin America was, in a sense, more open to foreign influence, ambitious in its social engineering, and in many ways more radical in its adoption of liberal and republican institutional models than Europe. It cannot be fully understood as a mere reaction, imitation, or consequence of developments in Europe or the United States. The way that the state, elites, and the lower strata of the population implemented their modernity remains a contribution of their own.

As Latin American marks of modernity, this paper has stressed the adoption of the one state-one nation model, the simultaneous formation of republican rule, the state and national identity, and definitions of the nation that included imaginings of open futures and uncertainty. Literature has identified some of these developments as defining moments of European modernity from the sixteenth century onwards. In Latin America, modernity took its own form and roots, especially in regard to those developments. Obviously, the conceptualization of the nation in the terms just described incorporated and imported European and North American modern notions of the state, civil society, institutions, and identity. Yet Latin American modernity and innovation in institutional design and nation-building cannot be fully understood by looking at these indicators alone.

Latin American modernizers believed, as will many socialist and Marxist governments and movements of the twentieth century that social engineering was not only possible but also desirable, and that government could and should craft the desired type of nation. Nineteenth century Latin American modernizers took to heart the modern nineteenth century idea that material development determined pretty much everything else, including morals. It was also based on the conviction that race, values, and "civilization" also needed to be part of the ingredients needed to construct the "right nation". This conviction was also present in the United States, but in the context of a different relation between liberty, virtue, and the institutions of the state.

1 David Apter, The Politics of Modernization (Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 1965) 1.

2 For great insights into this characterization of the Indies by the Kings and first conquerors, see Hugh Thomas, Rivers of gold: the Rise of the Spanish Empire; from Columbus to Magellan (New York: Random House, 2004).

3 José Carlos Mariátegui, Siete ensayos de interpretación de la realidad peruana (Lima: Editorial Amauta, 1952); Rodolfo Puiggros, De la Colonia a la Revolución (Buenos Aires: Partenon, 1949).

4 For a very good critique of these arguments, see Milciades Peña, Antes de Mayo (Buenos Aires: Ediciones Fichas, 1970).

5 For a discussion on Latin America as a "globalizer" rather than as a passive actor in the contemporary world, see Fernando Lopez-Alves and Diane Johnson, Globalization and Uncertainty in Latin America (London: McMillan, 2007). Introduction and chapter 1.

6 Amartya Sen, "How to Judge Globalism", The American Prospect 13.1 (2002).

7 Fernando Henrique Cardoso and Enzo Faletto, Dependency and Development in Latin America (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1979).

8 Some have done so. Despite the limitations of Eurocentric views they have nonetheless make a solid contribution. See for instance, Francois-Xavier Guerra, Modernidad e independencias: ensayos sobre las revoluciones hispánicas (Madrid: Mapfre, 1992).

9 For an argument about the importance of subaltern views and the need to include them in studies of the Latin American state, see Florencia Mallon, "Decoding the Parchments of the Latin American Nation State: Peru, Mexico, and Chile in Comparative Perspective", Studies in the Formation of the Nation State in Latin America, ed. James Dunkerley (London: Institute of Latin American Studies / University of London, 2002) 13-54.

10 José Luis Romero, Situaciones e ideologías en América Latina (Medellín: Editorial Universidad de Antioquia, 2001) 107.

11 See Fernando Lopez-Alves, State Formation and Democracy in Latin America (Durham: Duke University Press, 2000); see as well a similar argument in Miguel Angel Centeno, Blood and Debt: War and the Nation State in Latin America (Pennsylvania: The Pennsylvania University Press, 2002).

12 Peter Mandler, The English National Character: The History of an Idea from Edmund Burke to Tony Blair (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2006) 14-15.

13 Patriotism and nationalism are basically understood as the defense of what is "ours" against what is "foreign".

14 See, for instance, The New York Times [New York] 11 Jul. 1895: and The New York Times [New York] 17 Aug. 1902: 1.

15 Quoted in Omar Dahbour and Micheline Ishay, The Nationalism Reader (New Jersey: Humanities Press, 1995) 117.

16 José Ortega y Gasset, The Revolt of the Masses (New York: W.W. Norton & Company, 1932) 23.

17 Very likely, that was San Martin's intention because his goal was to promote republican rule over any other kind of government. His proposal tilted the Congress in his favor.

18 For a detailed discussion in reference to fascism and National Socialism, see George Mosse, The Nationalization of the Masses: Political Symbolism and Mass Movements in Germany from the Napoleonic Wars through the Third Reich (New York: Howard Ferting, 1975) 4-6.

19 Modris Eksteins, Rites of Spring: The Great War and the Birth of the Modern Age (Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company, 1989) 66-69; Paul Johnson, Modern Times: The World from the Twentieths to the Nineties (New York: Harper Perennial, 1983).

20 For a more expanded discussion of this topic, see Lopez-Alves, State Formation, introduction and conclusion.

21 For a comparative argument on the weakness of the state in Latin America, see Centeno, Blood and Debt; and Lopez-Alves, State Formation.

22 See Jared Becker, Nationalism and Culture: Gabriele D'Annunzio and Italy after the Risorgimento (New York: Peter Lange Editor, 1994).

23 Letter by Marquesa de Calderon de la Barca, 1841, cited in José Luis Romero, Latinoamérica: las ciudades y las ideas (Medellín: Editorial Universidad de Antioquia, 1999) 215.

24 Gonzalo Sánchez and Donny Meertens, Bandoleros, gamonales y campesinos (el caso de la violencia en Colombia) (Bogotá: El Áncora, 1983).

25 Ministerio de Relaciones Exteriores, Madrid, Legajo 2706, años 1854-1865. Carta de la delegación Española en Argentina al Consulado Español en Lisboa. No existe número de clasificación. Parte de un legajo titulado "Dirección de Asuntos Políticos", agosto de 1864.

26 The New York Times [New York] 21 Jul. 1890: 2.

27 The Times [London] 26 Jul. 26 1891: 1.

28 Walter D. Mignolo, Local Histories/Global Designs: Coloniality, Subaltern Knowledges, and Border Thinking (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2000).

29 To mention only some: see the famous 1189 lecture by Ernest Renan, "What is a Nation?", Becoming National, ed. Geoff Eley and Ronald Grigor Suny (New York: Oxford University Press, 1996) 41-55; Liah Greenfeld, Nationalism: Five Roads to Modernity (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1992); Eric Hobsbawam, "Inventing Tradition", The Invention of Tradition, Eric Hobsbawm and Terence Ranger (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1983) 1-14; John Luckacs, Democracy and Populism: Fear and Hatred (New Heaven: Yale University Press, 2005); Kohn, Hans, "The Nature of Nationalism", The American Political Science Review 33.6 (1939): 1001-1021; Benedict R. Anderson, Imagined Communities: Reflections on the Origin and Spread of Nationalism (London: Verso, 1983): and Under Three Flags: Anarchism and Anti-Colonial Imagination (London: Verso, 2005); Mandler; Yael Tamir, "The Enigma of Nationalism", World Politics 47.3 (1992): 421-423, and see his Liberal Nationalism (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1993).

30 Anderson, Imagined Communities 81.

31 James C. Scott, Seeing Like a State: How Certain Schemes to Improve the Human Condition Have Failed (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1998).

32 As opposed to what the literature has argued, authoritarian states have not been the only ones that resort to this nation making tool. Lewis Siegel Baum and Andrei Sokolov, Stalinism as a Way of Life: A Narrative in Documents (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2001): and Jeffrey Brooks, Thank You Comrade Stalin! Soviet Public Culture from Revolution to Cold War (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2001).

33 This model will be defined shortly below when discussing the notion of a nation-state as a symbol of modernity.

34 Eric Van Young, "The Raw and the Cooked: Elite and Popular Ideology in Mexico, 1800-1821", The Middle Period in Latin America: Values and Attitudes in the Seventeenth-Nineteenth Centuries, ed. Mark Szuchman (Boulder: Lynne Rienner, 1989).

35 See Timothy E. Anna, Forging Mexico: 1821-1835 (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1989) 5-25.

36 See Mandler.

37 There were exceptions; for instance, Paraguay under J. Gaspar Francia and Venezuela under C. Castro and J. Vicente Gomez, although in the case of Venezuela, Federalism was a topic of debate from the beginning.

38 Claudio Lomnitz, "Nationalism as a Practical System: Benedict Anderson's Theory of Nationalism from the Vantage Point of Spanish America", The Other Mirror: Grand Theory through the Lens of Latin America, eds. Miguel Ángel Centeno and Fernando Lopez-Alves (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2001) 329-359.

39 Literature on Mexico has attributed the creation of the nation to such an alliance. See, among others, Luis Villoro, El proceso ideológico de la revolución de independencia (México: UNAM, 1983); and Ernesto de la Torre Villar, La Independencia mexicana, 3 vols. (México: FCE, 1992).

40 Thomas Paine, Common Sense, the Rights of Man, reprint of 1791 edition (New York: Gryphon Editions, 1992) 58; and The Rights of Man (New York: Dolphin Books, 1961) 420.

41 G. W. F. Hegel, The Philosophy of History (New York: Willey Book Co., 1944) 86.

42 Sydney Pollard, The Idea of Progress: History and Society (London: ca Watts, 1968) 9.

43 Thomas Jefferson, Writings, ed. Merrill D Peterson (New York: Library of America, 1984) Notes on Virginia.

44 See an interpretation of the American nation as pre-existing the Union in Greenfeld.

45 Alexis Tocqueville, Democracy in America, electronic edition deposited and marked-up by asgrp, the American Studies Programs at the University of Virginia, June 1, 1997, 408-410. From the Henry Reeve Translation revised and corrected, 1899.

46 It can be argued that by the time of Alexander Hamilton and in 1801, when Thomas Jefferson assumed the presidency of the United States, the u.s. was not a nation yet. After that time, the state did expand and the federal government crafted a notion of the nation that featured openness and opportunity. Yet early religious utopian notions never ceased to exist in the popular imaginary and in the minds of most state-makers during the process of nation-building.

47 See, among others, Robert Bellah, "Civil Religion in America", Daedalus 117.3 (1988): 97-118.