Services on Demand

Journal

Article

Indicators

-

Cited by SciELO

Cited by SciELO -

Access statistics

Access statistics

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in

SciELO

Similars in

SciELO -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Lecturas de Economía

Print version ISSN 0120-2596

Lect. Econ. no.76 Medellín Jan./June 2012

ARTICLES

Wage Adjustment Practices and the Link between Price and Wages: Survey Evidence from Colombian Firms

Prácticas de ajuste salarial y la relación entre precios y salarios: Evidencia a partir de encuestas a empresas colombianas

Pratiques d'ajustement des salaires et le lien entre les prix et les salaires: résultats d'un sondage auprès des entreprises colombiennes

Ana Iregui*; Ligia Melo**; María Ramírez***

* Investigadora de la Unidad de Investigaciones de la Gerencia Técnica del Banco de la República. Dirección postal: Carrera 7 #14 -78, Piso 11, Bogotá-Colombia. Dirección electrónica: airegubo@banrep.gov.co.

** Investigadora de la Unidad de Investigaciones de la Gerencia Técnica del Banco de la República. Dirección postal: Carrera 7 #14 -78, Piso 11, Bogotá-Colombia. Dirección electrónica: lmelobec@banrep.gov.co.

*** Investigadora de la Unidad de Investigaciones de la Gerencia Técnica del Banco de la República. Dirección postal: Carrera 7 #14 -78, Piso 11, Bogotá-Colombia. Dirección electrónica: mramirgi@banrep.gov.co.

–Introduction. – I. Survey Design. –II. Wage Adjustment Practices. –III. The Link between Wage and Price Adjustments. –Conclusions. –References.

Primera versión recibida en septiembre de 2011; versión final aceptada en febrero de 2012

ABSTRACT

This paper explores firms' wage adjustment practices in the Colombian formal labor market; specifically, the timing and frequency of wage increases, as well as the link between wage and price changes. We use a survey of 1,305 firms belonging to all economic sectors. The results show that most firms adjust base wages annually, increases were concentrated around observed inflation and none of the firms cut wages. Moreover, factors associated with the performance of firms and workers alike are the main determinants of wage adjustments. The link between wages and price changes is stronger in sectors where labor costs represent a higher share of total costs and in firms operating in sectors with higher labor productivity.

Keywords: wage increases, labor market, survey evidence, logit models, Colombia.

JEL Classification: D22, J30, C25.

RESUMEN

Este artículo utiliza una encuesta a 1.305 firmas para evaluar las prácticas de ajustes salariales de las empresas en el mercado laboral colombiano. Específicamente, se analiza la frecuencia de los incrementos salariales y el vínculo entre los cambios de precios y salarios. Los resultados muestran que los salarios se ajustan anualmente, que los aumentos se concentran alrededor de la inflación observada y que ninguna empresa recortó los salarios. Además, los principales determinantes de dichos ajustes son factores asociados con el desempeño tanto de empresas como de trabajadores. La relación entre los cambios en salarios y precios es más fuerte en sectores donde los costos laborales representan una mayor proporción de los costos totales y en sectores con alta productividad laboral.

Palabras clave: incrementos salariales, mercado laboral, encuestas, modelos logit, Colombia.

Clasificación JEL: D22, J30, C25.

RÉSUMÉ

Cet article utilise un sondage auprès de 1305 entreprises pour évaluer les pratiques d'ajustement des salaires des entreprises sur le marché du travail en Colombie. Plus précisément, nous analysons la fréquence des augmentations de salaires et le lien entre les changements de prix et les salaires. Les résultats montrent, d'une part, que les salaires sont ajustés chaque année, d'autre part que les augmentations sont concentrées autour de l'inflation observée et, finalement, qu'aucune entreprise a réduit des salaires. Nous montrons également que les principaux déterminants de ces ajustements sont associés à la performance des entreprises ainsi qu'à celle des travailleurs. La relation entre l'évolution des salaires et des prix est plus forte dans les secteurs où les coûts salariaux représentent une proportion plus élevée des coûts totaux et dans les secteurs à forte productivité du travail.

Mots-clés: Hausse des salaires, études du marché du travail, modèles logit, Colombie.

Classification JEL: D22, J30, C25.

Introduction

Wage and price setting mechanisms play an important role in the transmission of monetary policy. According to Taylor (1999), when prices and wages are sticky, an increase in money supply affects output and employment in the short run. In the long run, however, the real economy is not affected by changes in money supply, because prices and wages gradually adjust and real money balances return to their initial level. The timing and frequency of wage-setting decisions are also relevant for the transmission of monetary policy to the real economy. In fact, monetary policy shocks should have larger effects on real variables after the decision on wage adjustments has been made and wages are relatively rigid. Conversely, when wage-setting decisions are uniformly distributed throughout the year and contracts last longer, the timing of monetary policy innovations within the year becomes less relevant (Olivei and Tenreyro, 2010).

In addition, the link between wage and price adjustments is important in terms of its implications for the effectiveness of monetary policy. Empirical evidence has shown price and wage-setting practices are quite heterogeneous and changes in these variables are not synchronized (e.g. Copaciu et al., 2010; Virbickas, 2010; Marques et al., 2010; Druant et al., 2009). These results could affect the size and the persistence of monetary policy shocks that affect output (Gali, 1994; Rotemberg and Woodford, 1999 and Taylor, 1999).

The aim of this paper is to shed light, at the microeconomic level, on firms' wage adjustment practices in the Colombian formal labor market through the use of a survey. In the existing literature, surveys at the firm level have focused mainly on wage rigidities.1 In this paper, we explore other aspects of wage-setting; specifically, the timing and frequency of wage increases as well as the link between wage and price changes. We use an ad hoc survey of 1,305 small, medium and large firms from all sectors of the economy, except the public sector. One of the main benefits of using surveys is the possibility of asking firms directly about wage-setting practices, which allows for information that could not be obtained from databases, either at individual or firm level. Also, the survey provides evidence for the microfoundation of the Central Bank's models.

The Eurosystem Wage Dynamics Network (WDN) conducted an ad hoc survey on price and wage-setting behavior among 17,000 firms in 17 countries of the European Union between the end of 2007 and the first half of 2008.2 Within this network, a study of the frequency, timing and the relationship between wage and pricing policies and adjustments was carried out by Druant et al. (2009) for 15 countries. The results show European firms adjust wages less frequently than prices and country characteristics (i.e., labor market institutions) are relevant for wage adjustments, whereas sectoral differences are crucial for price changes. They also found that wages and prices feed into each other at the firm level.

Moreover, as part of the WDN, Marques et al. (2010) provide evidence on price and wage dynamics for the Portuguese economy. Their findings show most of the firms change wages annually, mainly in January, which could be explained by collective bargaining agreements at the sectoral or firm levels. They also investigated the relationship between the timing of price and wage revisions and found the presence of some synchronization between price and wage changes for half the firms. Virbickas (2010) researched the wage and price-setting behavior of Lithuanian firms. The author found that Lithuanian firms adjust wages more than once a year, whereas adjustments in other countries within the WDN generally take place once a year. The results also indicate a firm's production technology, labor compensation practices and market competition might affect the frequency of wage and price changes.

Finally, Copaciu et al. (2010) studied the price-setting patterns of Romanian firms, also by means of an ad hoc survey, which includes a section on wage-setting behavior. They found wages are stickier than prices; firms change wages, especially in January; and wage adjustments are affected by changes in productivity.

In the case of Colombia, the literature on the link between price and wage changes is quite scant and focuses on the impact of the minimum wage on prices. For example, Misas and Oliveros (1994) evaluated the causality among several monthly indicators of prices (i.e. the Consumer Price Index) and wages (i.e. the Index of Industrial Wages and the minimum wage) during the period from January 1982 to March 1994. They found the minimum wage and the Consumer Price Index feed into each other in Granger's sense. Arango et al. (2010) study the effect of changes in the minimum wage on the price of food away from home during the period 1999-2008, using monthly prices by item at the establishment level. The authors found there is a contemporary response in prices to changes in the minimum wage. Specifically, a 10% increase in the minimum wage leads to a contemporary increase of 1.33% in the price of food away from home.

This paper contributes to that literature and provides insights for understanding wage-setting behavior and the connection between wage and price adjustments. The results show most of the firms surveyed adjust the base wages of their workers annually, mainly during the first quarter. This suggests wage changes in Colombia are time-dependent. Also, wage increases were concentrated around observed inflation and none of the firms cut wages. Moreover, factors associated to the performance of firms and workers alike are the main determinants of wage adjustments. Regarding the link between wage and price changes, our findings indicate this relationship is stronger in sectors where labor costs represent a higher share of total costs and in firms operating in sectors with higher labor productivity.

The paper is divided into four sections, apart from this introduction. In the second section, we briefly discuss the survey on which our analysis is based. We then go on to analyze the timing and frequency of wage adjustments and empirically study the factors that could determine wage increases. In the fourth section, we investigate the link between wage and price changes. The conclusions are described in the last section.

I. Survey Design

The analysis in this paper is based on a survey of 1,305 Colombian firms. The survey was designed to explore wage-setting mechanisms, the nature and sources of wage rigidities, and the link between wages and prices (Iregui et al. 2010a). In addition, the survey provided data on several firm characteristics (e.g. the economic sector, labor contracts, collective bargaining agreements and types of remuneration), which facilitated the characterization of firms in the empirical analysis. The survey also was designed to obtain responses for four occupational groups: managers, professionals, technicians and assistants, and unskilled workers.

A representative sample of firms was used for the survey. This allowed us to generalize the results to the population under study: namely 39,004 small, medium and large-scale legally constituted companies3 from all sectors of the economy, except the public sector.4 These firms are located in 13 cities and account for 70% of the formal employment in Colombia.5

Stratified random sampling was used to select the sample. Nine strata were considered. They correspond to the following economic sectors: agriculture, forestry and fishing; trade; construction; electricity, gas, water and mining; manufacturing; financial services; transport, storage and communications; education and health; and other services. It is worth noting that 1,305 firms replied to our survey. The firms that did not answer the questionnaire were replaced by companies with similar characteristics.6 The survey was applied during the first half of 2009, when the economy was showing signs of a slowdown in activity, low inflation and rising unemployment.

All the results presented henceforth are generalized for the population. Also, coefficients of variation (cve) were calculated for each answer. The estimates did not exceed 5%, indicating the reliability of the population estimates.

II. Wage Adjustment Practices

A. Timing and Frequency of Wage Changes

The survey inquired about practices regarding wage increases.7 This information is useful not only to determine whether wage adjustments follow a time-dependent rule or a state-dependent rule, but also to provide the Central Bank with several elements to guide monetary policy.8 In fact, according to Olivei and Tenreyro (2010), the synchronization of wage-setting decisions is important to the transmission of monetary policy to the real economy, since monetary policy innovations should have larger effect on real variables after the decision has been taken and wages are relatively rigid.

On the contrary, if wage-setting decisions are distributed uniformly throughout the year and contracts last longer, the timing of monetary policy innovations within the year becomes less relevant.9 For example, Olivei and Tenreyro (2010) indicate that wage-setting decisions in Japan and the United States are negotiated annually and are concentrated in the first two quarters of the year in Japan and in the final quarter in the United States. In France, wages are changed once a year, on average, with two separate spikes in the distribution of wage-setting decisions: one in January and the other in July (Druant et al., 2009). On the contrary, wage bargaining negotiations in Germany take place throughout the year, and contracts tend to last from one to three years.

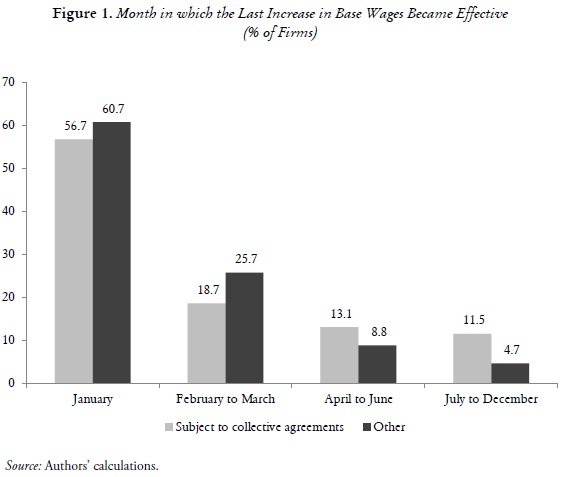

Regarding the frequency of wage changes, the results of our survey show over 95% of firms increase the base pay of their workers on a yearly basis.10 Annual wage adjustments do not take into account temporary price shocks that might arise during the year, preventing transitory inflationary shocks from becoming permanent. In addition, wage increases are concentrated in the first quarter, especially in January (Figure 1). These results suggest wage changes in Colombia are timedependent and support a wage adjustment, although such adjustments are not distributed equally throughout the year, as Taylor proposed originally (1999). Accordingly, monetary policy innovations should affect the real economy during the first quarter of the year.

Evidence supporting a time-dependent adjustment in base wages is reported for other countries as well. For example, the Wage Dynamics Network found with respect to the 17 European countries that belong to this project, about 60% of the firms, on average, adjust their wages once a year and 30% do so in January.11 Amirault et al. (2009) reported 89% of Canadian firms increase their wages at fixed intervals, whereas Babecký et al. (2008) found 56% of Czech firms adjust wages in January.

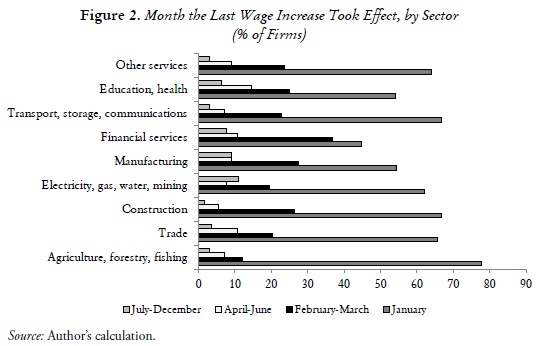

Moreover, the results of our survey, disaggregated by economic sector, show the same pattern emerges with a spike in the distribution of wage increases in January (Figure 2). However, it is worth noting that, although 44.6% of the firms in the financial services sector increased base wages in January, 36.9% did so during February and March; in the manufacturing and education and health sectors, about 54% of the wage increases were conducted in January, and close to 26% during February and March. In any case, the majority of firms in all sectors increase base wages during the first quarter.

Taking into account the importance of price and wage adjustment practices for the effectiveness of monetary policy, we compared our results to those of recent studies on price-setting behavior in Colombia. In general, the empirical evidence suggests time-dependent rules are more widespread in wage adjustments than in price changes. In fact, studies done for Colombia using both monthly price reports (Julio et al., 2009) and survey evidence (Misas et al., 2009) found substantial heterogeneity regarding time and statedependent price adjustment practices, contrary to the common practice of adjusting wages according to a time-dependent rule. For instance, Julio et al. (2009) found time dependency is more common in services subject to price regulation, such as education and health services and transport and communication, as well as in services highly dependent on minimum wages (e.g. food away from home, personal services and apparel). Conversely, the pricing rule for perishable food items was found to be state-dependent. In turn, Misas et al. (2009), who surveyed firms in the agricultural and manufacturing sectors, found 71.5% of firms review their prices according to the time-dependent rule, while 28.5% review prices when the economy is subject to some type of shock (state -dependent rule).

In addition, firms adjust wages less frequently than prices.12 According to our survey, wage adjustments generally are carried out annually (96% of the firms), mainly in January, whereas the results of price-setting behavior studies indicate the median duration of price spells for Colombian consumer prices is 6.4 months, when excluding the rental price of housing. Julio et al. (2009) also found prices are more flexible for goods than for services. The more flexible items are household utilities and perishable foods. Their price duration is close to four (4) months, while the least flexible are education and medical care services, with respective price durations of 16 months and 13 months. In turn, Misas et al. (2009) found firms in the manufacturing sector change prices less frequently than those in the agricultural sector.13

B. Wage Increases

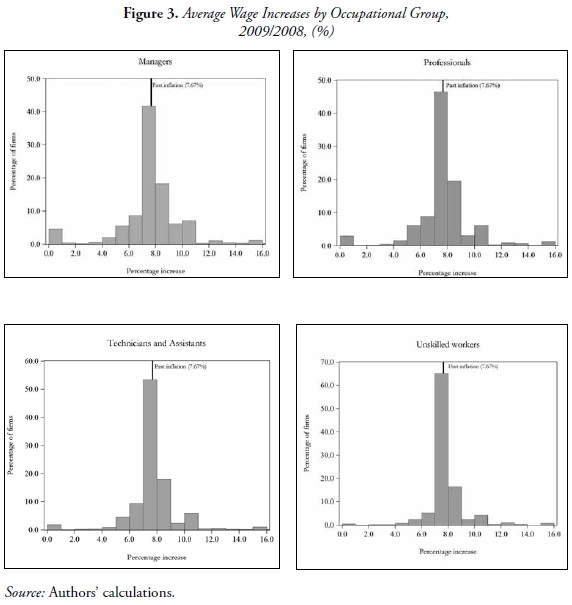

Regarding the last base wage increase, the majority of firms in the population under study made an average increase roughly equivalent to the rate of inflation observed in 2008 (7.67%). Figure 3 shows the histograms of the distribution of the average nominal wage change between 2008 and 2009, for each occupational position. As illustrated, none of the companies cut wages and there is a spike around the observed rate of inflation. In the case of unskilled workers, wage changes were concentrated near this value for about 60% of the firms, whereas this percentage is close to 40% for managers. The high concentration of observations around the reported inflation rate, especially in the case of unskilled workers, could be associated with the existence of a minimum wage in Colombia, which is adjusted annually according to past inflation.

In general, the histograms of the distribution of wage changes present evidence of wage rigidities for all occupational groups, since the data cluster around the observed inflation rate and there are no wage cuts. The high concentration of observations around past inflation might be evidence of downward real wage rigidity, which could be explained by the Colombian practice of adjusting wages, either in line with the inflation rate for the previous year or with the increase in the minimum wage. This result, together with the low frequency of wage changes, provides evidence of wage stickiness in the Colombian formal labor market.14

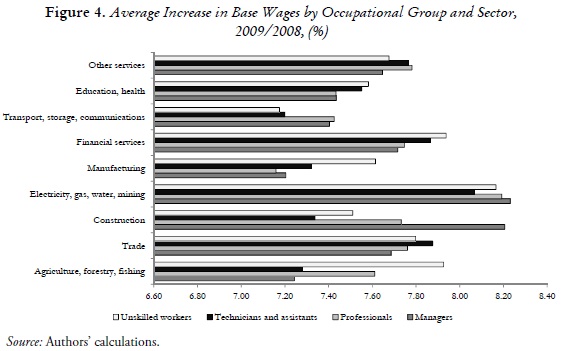

Finally, at the sectoral level, it is worth noting that the largest increases for all occupational groups were recorded in the electricity, gas, water and mining sector, whereas the smallest increases were in manufacturing, in the case of managers and professionals, and in transport, storage and communications, in the case of technicians and assistants and unskilled workers (Figure 4). As to wage increases by firm location and occupational group, the results show average base wage increases were higher in Bogotá for all occupational groups than in the rest of the country.

C. Determinants of Wage Increases

Next, to better understand the factors that firms consider when deciding on wage adjustments, we estimated cross-section models using both firm and sector characteristics. In particular, the dependent variable is the percentage of the 2008/2009 base wage increases. The explanatory variables allow for differences in economic sectors and geographical variability (location). We considered the electricity, gas, water and mining sector and cities other than Bogotá (the nation's capital) as the reference categories in the regression. Firm size also is included and is measured by the number of employees (Ln_employees). In addition, to take into account the characteristics and composition of the labor force, we included the share of managers and professionals (% skilled workers), the percentage of workers earning the minimum wage (% minimum wage earners),15 the percentage of workers earning comprehensive wages (% comprehensive wage earners), the share of employees on a permanent employment contract (% permanent workers), the share of employees on a temporary employment contract (% temporary workers), and the logarithm of the average wage for each occupational group (Ln_wages).

A dummy variable that takes the value of one (1) if the firm has any form of collective agreement (Collective agreements) was considered to evaluate the importance of collective wage agreements. Furthermore, we included dummy variables to account for the presence of flexible benefits and variable pay. Labor costs as a share of total costs also were included to approximate labor intensity. Finally, a dummy variable that takes the value of one (1) if the firm exports part of its production (d_exports) and a dummy that takes the value of one (1) if the firm is a subsidiary of a multinational company were included as well.

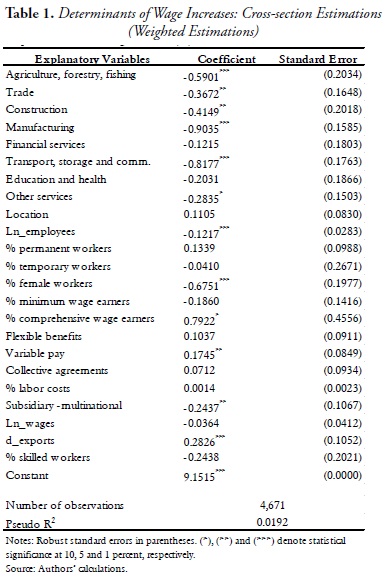

Table 1 shows the cross-section estimations, pooling together information for all occupational groups.16 According to the results, higher wage increases are observed, on average, in firms operating in the electricity, gas, water and mining sector than in any other sector. Regarding firm size, the coefficient is negative and significant, indicating that, for the year 2009, firms with fewer employees made, on average, higher wage increases. Moreover, firms with a higher percentage of female workers, on average, made smaller wage increases. The presence of variable pay and the percentage of employees earning comprehensive wages are statistically significant and positive in explaining wage increases. Finally, wage increases are higher in exporting firms than in non-exporting ones, possibly indicating that higher revenues from exports (total Colombian exports increased 25% during 2007/2008) resulted in larger wage increases.

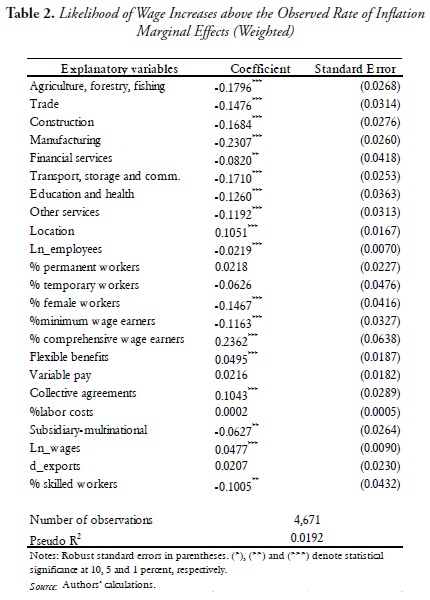

An additional exercise was conducted to identify several factors that could affect the likelihood of the average wage increase being higher than the observed rate of inflation. To this end, a logit model was estimated using the pooled data mentioned earlier. The dependent variable takes the value of one (1), if the firm decided on average wage increases above past inflation, and zero, if not. In the case of managers it should be noted that 39% of firms increased wages above past inflation; in the case of professionals, technicians and assistants and unskilled workers, these percentages were 36%, 33% and 30%, respectively.

Marginal effects were calculated at the means of the independent variables (Table 2). As can be seen, when comparing sectoral probabilities to the reference category (electricity, gas, water and mining), the coefficients for all sectors are negative and significant, suggesting that firms in the electricity, gas, water and mining sector are more likely to increase wages above inflation.

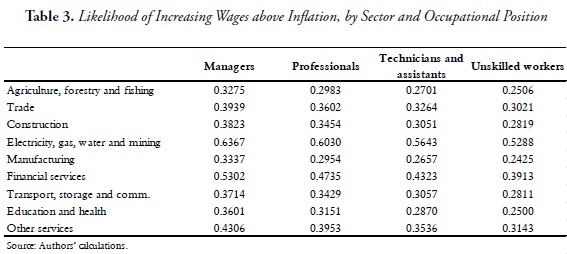

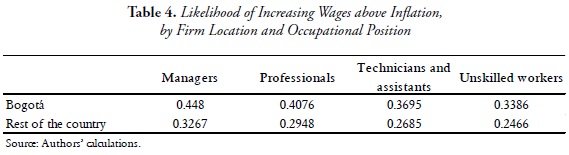

In fact, when calculating average probabilities by sector, the results show these probabilities are higher in the electricity, gas, water and mining sector, followed by the financial services sector, whereas the lowest probabilities were found in the agriculture, forestry and fishing and manufacturing sectors.17 Also, the probability of increasing wages above inflation increases for all economic sectors with the qualification of the labor force (Table 3). Regarding firm location, those located in Bogotá are more likely to increase wages above inflation than firms located in the rest of the country. When looking at each occupational position, the same results emerged (Table 4).

As to the number of employees, logit estimates indicate the higher the percentage of female workers and the share of skilled workers, the less the likelihood of wages being increased above inflation (Table 2). The likelihood also decreases if the firm is a subsidiary of a multinational company. Furthermore, when the share of minimum wage earners increases, the probability of increasing wages above inflation declines. This could be explained by the fact that the minimum wage increase for 2008/2009 was equal to the observed rate of inflation. On the contrary, the likelihood of raising wages above inflation increases, if the firm has flexible benefits, a higher percentage of comprehensive wage earners and a higher average wage level. Finally, the probability increases if the firm has any kind of collective agreement, which could indicate its employees have more bargaining power when deciding wage adjustments.

D. Relevant Factors in Determining Base Wage Increases

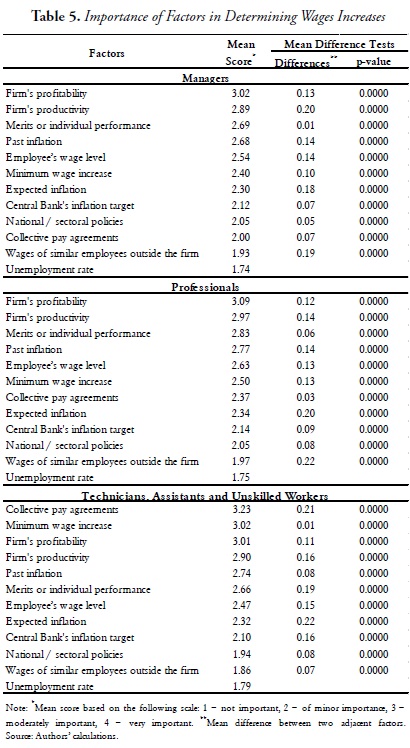

We also asked the firms surveyed about the aspects affecting wage increases. Specifically, the respondents were asked to rate, on a scale of one (1) (not important) to four (4) (very important), the importance of certain factors in determining base wage changes. These factors included the firm's profitability, its productivity, merits or individual performance, past inflation, employee's wage level, minimum wage increase, expected inflation, the central bank's inflation target, national / union policies, collective pay agreements, wages of similar employees outside the firm, and the unemployment rate. We calculated the mean score of the answers to allow for comparisons. Following Blinder (1991), a mean score greater than or equal to 3.0 is considered as excellent and a score of less than 1.5 as very poor; a mean score greater than or equal to 2.5 is considered as reasonably strong.

Table 5 shows the ranking of factors according to the importance assigned by the firms (average score).18 In general, one sees the factors associated with the firm's performance are the main determinants of wage adjustments, followed by factors associated with the worker's performance. Subsequently, the firms rank inflation and the minimum wage increase. Finally, firms consider aggregate factors, such as unemployment, and national/sectoral policies, as less important in defining wage increases.

Specifically, in the case of managers and professionals, the firm's profitability is the factor reported by firms as being the most important when determining wage increases, followed by the firm's productivity, merits or individual performance, past inflation and the employee's wage level.

The existence of collective agreements and the minimum wage increase are the most important factors in determining wage increases for technicians, assistants and unskilled workers. In general, these results are similar to those observed at the sectoral level. However, in the case of managers and professionals, past inflation is the factor that firms reported as being the most important for wage increases in the financial services sector and in education and health.

One of the main interests of this survey was to inquire about the relevance of inflation in wage increases. For this reason, past inflation, expected inflation and the central bank's inflation target were included in the list of important factors determining wage increases. The ranking of the various alternatives indicates firms are backward looking, since past inflation is more important to them when determining wage increases. In particular and for all occupational positions, about 60% of the firms consider past inflation as important or very important. Conversely, 42% of the firms expected inflation to be important or very important when considering wage adjustments. Moreover, although the Central Bank announces the inflation target before the start of wage negotiations, 35% of the firms surveyed consider the central bank's target as important or very important.

Next, we estimate ordered logit models19 to control for firm characteristics that might explain the main factors firms take into account when defining base wage increases. The dependent variable increases with the importance of considering such factors. It takes values from one (1) to four (4), where 1 = not important, 2 = of minor importance, 3 = moderately important and 4 = very important. We used the same set of benchmark explanatory variables as before. In addition, we introduced dummy variables to account for the different occupational positions, with less skilled workers being the reference category. In all models, we maintained the four categories for the dependent variables, since the threshold parameters estimated are statistically different from one another.20

To simplify presentation of the results, Table 6 shows the marginal effects on the highest probability category (very important) for the ordered logit model. For the alternatives associated with the performance of the firms, such as their profitability and productivity, the results show these factors are more important for managers and professionals than for less skilled workers. In addition, as the number of employees of the firm increases and for firms that use variable pay as part of their remuneration package, the likelihood of considering these firms features as determinants of wage adjustment increases. Furthermore, as the average wage increases, the likelihood declines. In the case of the firm's profitability, the estimates suggest the likelihood of considering this factor reduces as the percentage of employees earning the minimum wage and the percentage of employees on permanent contracts increases. In turn, the probability that a firm considers its productivity as an important factor increases for firms that are subsidiaries of multinational companies.

Regarding workers' characteristics, such as merits or individual performance and the employee's wage level, the results indicate the likelihood of considering these factors increases when the firm is a subsidiary of a multinational company and when the firm uses variable pay. It declines as the number of employees earning minimum wages increases. Specifically, the probability of firms taking individual performance into account in wage adjustments increases with firm size and for exporting firms. On the contrary, the probability of considering this factor as important declines among firms with collective pay agreements, where wage adjustments are negotiated between employees and employers. The estimates indicate the average wage level is an important factor in determining wage adjustments only in the case of managers and professionals. As expected, the share of labor cost negatively affects the probability of considering the average wage level as an important factor in wage adjustments.

Turning to the role played by inflation (i.e. past inflation, expected inflation and the inflation target), the results show firm size positively affects the likelihood of firms considering this factor as important when defining wage increases. Similarly, the presence of collective agreements and variable pay has a positive effect on that probability. Also, for managers and professionals, the probability of taking inflation into account as an important factor when determining wage adjustments is higher with respect to less skilled workers.

When considering the annual minimum wage increase, the estimates show the likelihood of using this factor as important in wage adjustments for managers and professionals is lower than for less skilled workers. In turn, firms with collective agreements are more likely to consider this factor than the other firms. In addition, the share of employees earning the minimum wage also has a positive influence, as expected. The presence of flexible benefits acts in the opposite direction, as does the share of employees on a permanent employment contract and the average wage level.

Finally, for firms with collective agreements, the likelihood of considering such agreements is lower for managers and professionals than less skilled workers. The share of labor costs and the percentage of workers on permanent contracts have a negative impact on the likelihood of considering collective agreements when defining wage increases.

III. The Link between Wage and Price Adjustments

The interaction between wage and price adjustments is important for central banks, given the implications for the effectiveness of monetary policy.21

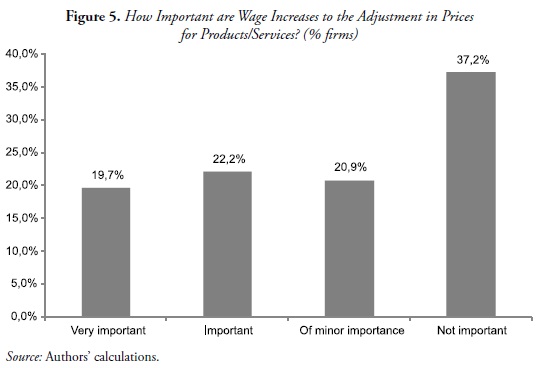

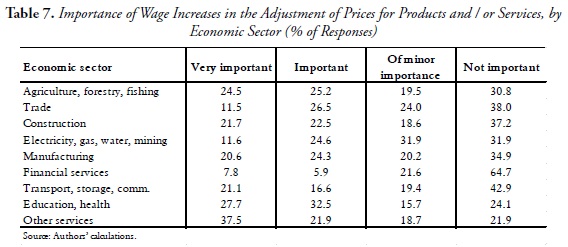

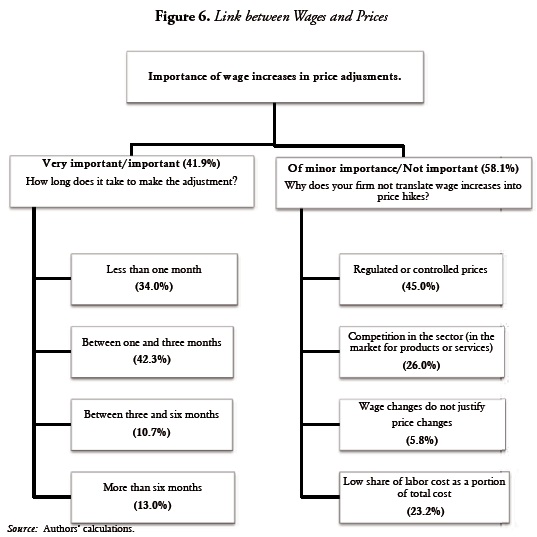

The survey asked firms about the relevance of this link for Colombian firms. Specifically, we questioned firms about the importance of wage increases when it comes to adjusting the price of their products/services. The results show wage adjustments are not important for 37.3% of the firms and of minor importance to 20.9% when changing prices, whereas for 19.7% and 22.2% of the firms see wage adjustments as very important and important, respectively (Figure 5).22 These results are similar to those found in Europe, where 15% of the firms report a relative strong link between prices and wages (Wage Dynamics Network, 2009).

Although there generally is not a relative strong relationship between wage and price changes, the pass-through of wages to prices is particularly high in some sectors. For instance, wage increases are important or very important in setting prices for roughly 60% of the firms in the education and health sector and in other services; the same is true for nearly 50% of the firms in the agriculture, forestry and fishing sector (Table 7), which account for nearly 14% of the consumer price index basket, according to an approximate estimate. These results also suggest the interaction between wages and prices is stronger in sectors where labor costs account for a larger share of total costs. In fact, our survey results indicate the average labor cost share is about 40% for education and health and other services.

For 86.3% of the firms in the financial services sector and 63.8% of the firms in the electricity, gas, water and mining sector the link between wage and price adjustment is of minor importance or not important. Taking firm size into consideration, there is no significant variation across firms; this link is important or very important for 41.9% of the small firms surveyed, 44.9% of the medium-sized firms and 38.7% of the large firms.

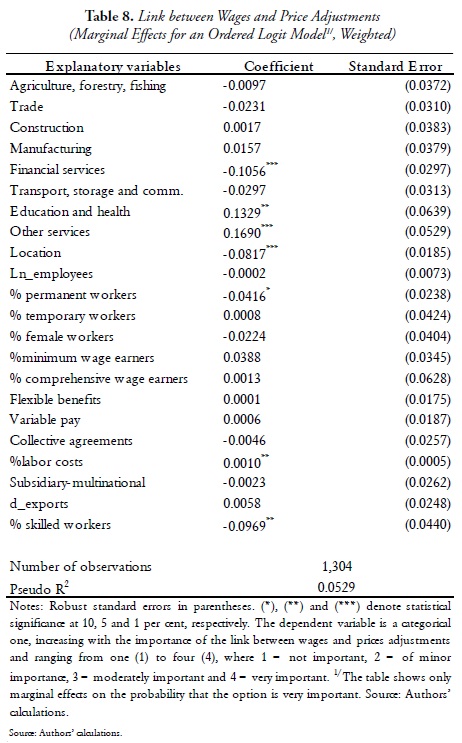

The characteristics of firms could help us to understand whether or not they influenced the link between wage and price adjustments. Hence, an ordered logit model was estimated. The dependent variable increases with the importance of the interaction between both variables. It takes values from one (1) to four (4), where 1 = not important, 2 = of minor importance, 3 = moderately important and 4 = very important. Table 8 shows the marginal effects of the highest probability category (very important). The results confirm that an increase in labor costs as a share of total costs, as a proxy of labor intensity, raises the likelihood that wages will pass-through to prices. This result is consistent with the findings of Bertola et al. (2010) and Druant et al. (2009), based on the Wage Dynamic Network survey, which found a strong relationship between a high labor share and the pass-through of wages to prices. Furthermore, firms operating in the education and health and other services sectors, where the labor share is the highest, are more likely to pass wage increases on to prices than in the reference sector (electricity, gas, water and mining).

Conversely, the pass-through of wages to prices is less likely in the financial sector. In turn, as the proportion of technicians and unskilled workers increases with respect to managers and professionals and for firms located in cities other than the capital, so does the probability of wage increases being incorporated into price increases.

An additional ordered logit estimation was done with sectoral variables such as capital intensity, measured as the ratio of gross operating surplus to employee compensation and labor productivity.23 According to the findings, firms operating in sectors with higher labor productivity are more likely to pass wage increases on to prices. Conversely, the pass-through of wages to prices is less for firms in sectors with higher capital intensity.

In the case of firms that indicated wage increases are important or very important in price adjustments, we asked how long it took them to adjust prices once the wage change took place. The results show 34% of these firms transfer wage increases to prices in less than a month, 42.3% do so between one and three months and 10.7% between three and six months. The remaining 13% take more than six months to pass wage increases on to prices (Figure 6). A breakdown by sector shows some differences. In particular, firms involved in education and health, agriculture, forestry and fishing, and other services, which are the sectors with the highest share of labor costs, are quicker about translating wage increases into prices than firms in the remaining sectors. In fact, around 45% of these firms pass wage increases on prices in less than one month. With regard to firm size, the results show little variation.

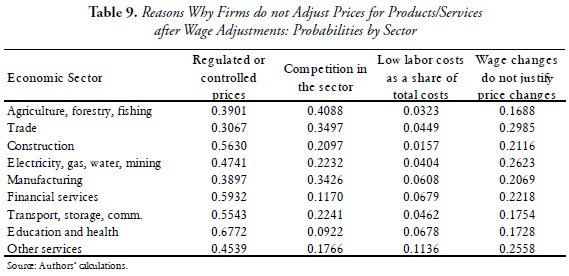

Finally, the firms that indicated wage increases are of minor importance or not important for price adjustments argued the most important reasons for not changing their prices were the presence of controlled or regulated prices (45%), competition in their sector (26%), the wage increase that does not justify a price change (23.2%), and low labor costs as a share of total costs (5.8%) (Figure 1). Some differences emerged at the sectoral level. For example, firms involved in the financial services, construction, transport, storage and communications, and electricity, gas, water and mining sectors do not pass wage increases on to prices, mainly due to the presence of regulated or controlled prices. The probabilities obtained from a multinomial logit model in which the dependent variable corresponds to each of the reasons for not adjusting prices after wage increases, confirm that regulated or controlled prices is the most important reason in most sectors for not changing prices (Table 9). In turn, competition in the sector is an important reason for not transferring wage increases into price hikes for firms in the trade, manufacturing and agricultural sectors, which are sectors generally subject to more competition.

Conclusions

This paper provides elements to understand the wage adjustment practices firms use, as well as the link between wage and price changes in the Colombian formal labor market, since we directly ask firms about their wage-setting policies. Specifically, we surveyed 1,305 small, medium and large firms belonging to all sectors of the economy, except the public sector. The results show over 95% of the firms surveyed increase their workers' base pay annually, mainly during the first quarter, suggesting that wage changes in Colombia are time-dependent. Accordingly, monetary policy innovations should have smaller effects on the real economy during the first quarter of the year.

When comparing our results to those of recent price-setting studies for Colombia, we found firms adjust wages less frequently than prices. In fact, the results from the price-setting behavior studies indicate the median duration of price spells is about six months for Colombian consumer prices, excluding the rental price of housing, whereas wage adjustments generally are carry out annually. The empirical evidence also suggests time-dependent wage adjustments are more common than time-dependent price changes.

Regarding base wage increases, the majority of firms in the population under study made an average increase close to observed inflation and none of the companies cut wages. These findings could suggest the presence of downward wage rigidity, which can be explained by the Colombian practice of adjusting wages in line with the inflation rate of the previous year or with the increase in the minimum wage. This result, coupled with the low frequency of wage changes, provides evidence of wage stickiness in the Colombian formal labor market. Moreover, the high concentration of observations near observed inflation rate, especially in the case of unskilled workers, could be associated with the existence of a minimum wage in Colombia, which is annually adjusted according to past inflation.

When we asked the firms under study about the aspects affecting wage increases, their responses point to factors associated with the firm's performance as the main determinants of wage adjustments, followed by worker performance. Next, the firms take into account the behavior of inflation and the minimum wage increase. Firms rank aggregate factors such as unemployment and national / sectoral policies as less important in defining wage increases. Concerning the role of inflation in wage adjustments, the survey findings indicate firms are backward looking; for them, past inflation is more important than expected inflation when determining wage increases. In addition and even though the Central Bank announces the inflation target prior to the start of wage negotiations, 35% of firms consider the central bank's target as important or very important.

Given the implications of the interaction between wage and price adjustments for the effectiveness of monetary policy, the survey asked firms about the importance of wage increases in the adjustment of the prices for their products/services. The results show wage adjustments are not important to 37% of the firms when changing prices, whereas 20% consider them to be very important. Although the relationship between wage and price changes is not especially strong, the pass-through of wages to prices is particularly high in some sectors. For example, wage increases are important or very important in setting prices for around 60% of the firms surveyed in the education and health sector and in other services. These results suggest the interaction between wages and prices is stronger in sectors where labor costs as a share of the total cost is higher. Additionally, firms operating in sectors with higher labor productivity are more likely to pass wage increases on to prices. Conversely, the pass-through of wages to prices declines in sectors with higher capital intensity.

References

Agell, Jonas and Lundborg, Per (1995). ''Theories of Pay and Unemployment: Survey Evidence from Swedish Manufacturing Firms'', Scandinavian Journal of Economics, Vol. 97, No. 2, pp. 295-307. [ Links ]

Agell, Jonas and Lundborg, Per (2003). ''Survey Evidence on Wage Rigidity and Unemployment: Sweden in the 1990s'', Scandinavian Journal of Economics, Vol. 105, No. 1, pp. 15-29. [ Links ]

Amirault, David; Fenton, Paul and Laflèche, Thérèse (2009). ''Asking about Wages: Results from the Bank of Canada's Wage Setting Survey'', Paper presented at the XIV Meeting of the Central Bank Researchers Network of the Americas, Salvador, Bahía, Brazil, 11 – 13 November. [ Links ]

Arango, Luis Eduardo; Ardila, Luz Karine and Gómez, Miguel Ignacio (2010). ''Efecto del cambio del salario mínimo en el precio de las comidas fuera del hogar en Colombia'', Borradores de Economía, #584, Banco de la República. [ Links ]

Babecký, Jan; Dybczak, Kamil and Galuš ák, Kamil (2008). ''Survey on Wage and Price Formation of Czech Firms'', Czech National Bank, Working Paper Series, # 12, December. [ Links ]

ák, Kamil (2008). ''Survey on Wage and Price Formation of Czech Firms'', Czech National Bank, Working Paper Series, # 12, December. [ Links ]

Babecký, Jan; Du Caju, Philip; Kosma, Theodora; Lawless, Martina; Messina, Julián and Rõõm, Tairi (2010). ''Downward Nominal and Real Wage Rigidity: Survey Evidence from European Firms'', Scandinavian Journal of Economics, Vol. 112, No. 4, pp. 884-910. [ Links ]

Bertola, Giuseppe; Dabusinskas, Aurelijus; Hoebericht, Marco; Izquierdo, Mario; Kwapil, Claudia; Montornès, Jeremi and Radowski, Daniel (2010). ''Price, Wage and Employment Response to Shocks: Evidence from the WDN Survey'', Deutsche Bundesbank, Discussion Paper Series 1, Economic Studies, No 02/2010. [ Links ]

Bewley, Truman (1995). ''A Depressed Labor Market as Explained by Participants'', The American Economic Review, Vol. 85, No. 2, Papers and Proceedings, pp. 250-254. [ Links ]

Bewley, Truman (1998). ''Why not Cut Pay?'', European Economic Review, Vol. 42, No. 3-5, pp. 459-490. [ Links ]

Bewley, Truman (1999). Why Wages don't Fall during a Recession. Cambridge, Harvard University Press. [ Links ]

Blinder, Alan and Choi, Don (1990). ''A Shred of Evidence on Theories of Wage Stickiness'', Quarterly Journal of Economics, Vol. 105, No. 4, pp. 1003-1015. [ Links ]

Blinder, Alan (1991). ''Why are Prices Sticky? Preliminary Results from an Interview Study'', The American Economic Review, Vol. 81, No. 2, pp. 89-96. [ Links ]

Campbell, Carl and Kamlani, Kunal (1997). ''The Reasons for Wage Rigidity: Evidence from a Survey of Firms'', Quarterly Journal of Economics, Vol. 112, No. 3, pp. 759-789. [ Links ]

Copaciu, Mihai; Neagu, Florian and Braun-Erdei, Horia (2010). ''Survey Evidence on Price Setting Patterns of Romanian Firms'', Managerial and Decision Economics, Vol. 31, No. 2-3, pp. 235-247. [ Links ]

Druant, Martine; Fabiani, Silvia; Kezdi, Gabor; Lamo, Ana; Martins, Fernando and Sabbatini, Roberto (2009). ''How are Firms' Wages and Prices Linked: Survey Evidence in Europe'', Working Paper, # 174, National Bank of Belgium. [ Links ]

Gali, Jordi (1994). ''Monopolistic Competition, Business Cycles, and the Composition of Aggregate Demand'', Journal of Economic Theory, Vol. 63, No. 1, pp. 73-96. [ Links ]

Iregui, Ana María; Melo, Ligia Alba and Ramírez, María Teresa (2009). ''Are Wages Rigid in Colombia? Empirical Evidence Based on a Sample of Wages at the Firm Level. Borradores de Economía, #571i, Banco de la República. [ Links ]

Iregui, Ana María; Melo, Ligia Alba and Ramírez, María Teresa (2010a). ''Incrementos y rigideces de los salarios en Colombia: Un estudio a partir de una encuesta a nivel de firma'', Revista de Economía del Rosario, Vol. 13, No. 2, pp. 279-311. [ Links ]

Iregui, Ana María; Melo, Ligia Alba and Ramírez, María Teresa (2010b). ''Downward Wage Rigidities and Other Firms' Responses to an Economic Slowdown: Evidence from a Survey of Colombian Firms'', Borradores de Economía, # 612, Banco de la República. [ Links ]

Julio, Juan Manuel; Zárate, Héctor Manuel and Hernández, Manuel Darío (2009). ''The stickiness of Colombian Consumer Prices'', Ensayos sobre Política Económica, Vol. 28, No. 63, pp. 100-152. [ Links ]

Kawaguchi, Daiji and Ohtake, Fumio (2008). ''Testing the Morale Theory of Nominal Wage Rigidity'', Industrial & Labor Relations Review, Vol. 61, No. 1, Article 3. [ Links ]

Marques, Carlos Robalo; Martins, Fernando and Portugal, Pedro (2010). ''Price and Wage Formation in Portugal'', European Central Bank, Working Paper Series # 1225. [ Links ]

Misas, Martha; López, Enrique and Parra, Juan Carlos (2009). ''La formación de precios en las empresas colombianas: evidencia a partir de una encuesta directa'', Borradores de Economía, # 569, Banco de la República. [ Links ]

Misas, Martha and Oliveros, Hugo (1994). ''La relación entre salarios y precios en Colombia: Un análisis econométrico'', Borradores de Economía, # 7, Banco de la República. [ Links ]

Parra, Juan Carlos; Misas, Martha and López, Enrique (2010). ''Heterogeneidad en la fijación de precios en Colombia: Análisis de sus determinantes a partir de modelos de conteo'', Borradores de Economía, # 628, Banco de la República. [ Links ]

Olivei, Giovanni and Tenreyro, Silvana (2010). ''Wage Setting Patterns and Monetary Policy: International Evidence'', Journal of Monetary Economics, Vol. 57, No. 7, pp. 785-802. [ Links ]

Rotemberg, Julio and Woodford, Michael (1999). ''The Cyclical Behavior of Prices and Costs''. In: Taylor, John and Woodford, Michael (Eds.), Handbook of Macroeconomics (Vol. 1, Part 2, 1051-1135). Elsevier. [ Links ]

Taylor, John (1999) ''Staggered Price and Wage Setting in Macroeconomics''. In: Taylor, John and Woodford, Michael (Eds.), Handbook of Macroeconomics (Vol. 1, Part 2, 1009- 1050).Elsevier. [ Links ]

Virbickas, Ernestas (2010). ''Wage and Price Setting Behavior of Lithuanian Firms'', European Central Bank, Working Paper Series, # 1198. [ Links ]

Wage Dynamics Network (2009). ''Wage Dynamics in Europe: Final Report of the Wage Dynamics Network (WDN)'', December. Available at: http://www.ecb.europa.eu/home/pdf/wdn_finalreport_dec2009.pdf (February 9, 2010). [ Links ]

Notas

* The authors are senior researchers with the Research Unit of the Deputy Governor's Office at Banco de la República. We would like to thank Adolfo Cobo and Rafael Puyana for their comments, as well as Karina Acosta for her research assistance. The participation of the firms that agreed to complete the survey also is appreciated. The opinions expressed herein are those of the authors and doa not necessarily reflect the views of Banco de la República or its Board of Directors.

1 See for example, Agell and Lundborg (1995, 2003), Amirault et al. (2009), Babecký et al. (2010), Bewley (1995, 1998, 1999), Blinder and Choi (1990), Campbell and Kamlani (1997), Copaciu et al. (2010) and Kawaguchi and Ohtake (2008).

2 For details on the WDN firm survey, see European Central Bank, Wage Dynamics in Europe: Final Report of the Wage Dynamics Network (WDN), December 2009.

3 Firms with less than 10 employees were excluded.

4 The public sector was excluded, because the wages of public employees are set mostly by government decree.

5 The cities are Bogotá, Bucaramanga, Barranquilla, Cali, Cartagena, Medellín, Manizales, Pereira and their metropolitan areas. Barrancabermeja, Buga, Tuluá, Girardot and Rionegro also were included.

6 For details regarding the survey design and its implementation, see Iregui et al., 2010a.

7 A Spanish version of the complete questionnaire is available in Iregui et al. (2010a).

8 In a time-dependent rule firms revise their wages at fixed time intervals, while in a statedependent rule, wage decisions depend on the state of the economy (Taylor, 1999).

9 From the perspective of the model, what is relevant is the time when the negotiation is carried out, rather than the date when the outcome takes effect (Olivei and Tenreyro, 2010).

10 For employees subject to collective bargaining agreements and for all other employees, 97% and 96% of the firms increase the base pay of their workers on a yearly basis, respectively.

11 See Wage Dynamics Network (2009).

12 This result is consistent with the evidence found by Druant et al. (2009) for European countries, where wages tend to remain unchanged for nearly 15 months, on average, while prices stay constant for around 10 months.

13 Based on a price-setting survey, Parra et al. (2010) found the frequency of price changes is determined mainly by product features, the degree of competence facing the firm, contractual agreements and the economic sector where the firm operates.

14 See Iregui et al. (2009 and 2010b) for an analysis of downward wage rigidities in Colombia.

15 Comprehensive wages (salario integral) not only include the base wage. They also compensate, in advance, the value of benefits such as severance pay, non-statutory benefits and overtime.

16 Additional estimations were done by occupational position. However, no significant differences among these groups were found. Hence, it was decided to present a single estimation by pooling the information for all categories.

17 A model including sectoral labor productivity as an additional regressor was estimated as well. The results, not reported here, indicate the likelihood of increasing wages above inflation increases in more productive sectors, such as the electricity, gas, water and mining sector.

18 The average scores obtained were ordered and t statistics were calculated for each option to test whether the mean differences between contiguous alternatives were statistically significant. In all cases, the results show the null hypothesis of equal average scores is rejected, with a confidence level of 99%.

19 As in the previous case, we estimated a single model by pooling together the information for all occupational groups.

20 A Wald test was used to test the difference among the threshold parameters. The results of the tests, as well as the marginal effects for all the models, may be obtained from the authors upon request.

21 See for example Druant et al. (2009) and Wage Dynamics Network (2009).

22 In their survey of price-setting behavior for the manufacturing and agricultural sectors, Misas et al. (2009) found changes in the cost of raw materials and changes in the prices charged by competitors are the main factors firms consider when adjusting prices, while labor costs are one of the least important reasons when deciding on price changes. In the particular case of food away from home, Arango et al. (2010) found there is a contemporary response in prices to changes in the minimum wage.

23 Results are not reported here, but are available upon request.