On Argentina’s Currency Crisis of 2018

Argentina painfully became the world’s riskiest sovereign borrower behind Venezuela in 2018. Its national currency, the Argentine peso, lost more than 50 % in value against the dollar in just the first 8 months of the year, contributing to rising inflation and soaring interest rates. Argentina had to ask for financial assistance from the International Monetary Fund (IMF), and the country obtained a $50-billion bailout package in June, the biggest loan in the IMF’s history. In addition to the IMF’s financing deal, Argentina’s central bank jacked up its benchmark interest rate to 60 % — the highest in the world — in late August in a struggle to fight galloping inflation and stabilize the peso, which plunged to record lows.

Having rich natural resources and being one of the world’s major agricultural producers, Argentina’s economy – the third largest in Latin America – was supposed to be a high-income economy. How did Argentina get itself into a crisis situation with rampant inflation and a collapsing currency? Sadly, the crisis finds its root in the country’s prolonged severe economic mismanagement.

I. Gross Economic Mismanagement

The seeds of the current crisis can arguably be traced back to the government headed by Cristina Kirchner from December 2007 to November 2015. Kirchner was elected based on her popularity among the suburban working class and the rural poor. Pursuing a populist-socialist agenda, Kirchner’s government borrowed money and spent massively on both social programs and subsidies to appease and solidify her political base. As a result, Argentina’s debt skyrocketed, with deficit spending financed in part by extensive foreign borrowing. Such borrowing was hardly sustainable, causing long-term problems to the economy. Nevertheless, the free-spending Argentine government did not seem to care at all. When foreign borrowing was not enough, it turned to borrowing from the central bank to fund public spending, leading to rapid money growth and rising inflation. The government even nationalized private pension funds to pay its debt. The deficit-financed spending spree drove both inflation and interest rates up. The more the Argentine government borrowed, the more expensive credit became for private businesses. High borrowing costs – coupled with increasingly tough regulations of the private sector – strangled business investment, leaving Argentina’s economy in disarray and unemployment surging. As the economy deteriorated, tax receipts fell substantially, further worsening the government’s fiscal position. Meanwhile, Argentina’s inflation kept going up, reducing its export competitiveness. The country’s persistent fiscal deficit also drove up demand for imports and contributed to a widening current account deficit. This made Argentina even more reliant on foreign capital inflows to finance its deficit, thereby increasing the country’s vulnerability to capital outflows.

The center-right Mauricio Macri, a former mayor of Buenos Aires, got elected and took office as the new President of Argentina in December 2015 on campaign promises to revive an economy crippled by his predecessor’s populist social programs and regulations. The problems of rocketing inflation and excessive foreign debt, however, proved to be too daunting for the new Argentine government to solve anytime soon. In fact, the country’s foreign debt continued to soar under Macri’s government. Apparently, there was no easy solution. Any efforts to roll back public spending and subsidies put in place by the previous Kirchner administration could likely raise social discontent and meet strong political opposition. While Macri’s government struggled to cut deficits, tame inflation, and service debt in foreign currencies, the country’s already dire situation was exacerbated by two significant unfavorable events beyond Macri’s control – one domestic and the other one external.

II. Major Adverse Economic Shocks

Export earnings are vital for Argentina because they can help generateforeign exchange revenues needed to pay for imports and to service and repay foreign debt. Argentina’s agriculture industry is its key engine of growth, with processed and unprocessed products of agricultural origin (e.g., soybean, corn, and wheat) accounting for more than half of the country’s exports.

Unfortunately, Argentina was hit by a historical drought in the 2017-2018 growing season. The drought dealt a serious blow to Argentina’s exports and tax collection, causing its economy to contract. This heightened the country’s economic frailty. Additionally, the continuing strength of the U.S. dollar made Argentina’s situation even worse. The Federal Reserve’s rate hiking cycle was well under way as the U.S. economy got stronger. The rising U.S. interest rates induced investors to pull money out of emerging-market countries like Argentina, thereby piling considerable pressure on the Argentine peso. Moreover, the marked depreciation of the peso pushed up import costs and fueled higher inflation in the Argentine economy. A stronger dollar also made Argentina’s sizeable dollar debt more difficult to service and repay, thus further deepening the nation’s economic woes.

Soaring price inflation weighed heavily on Argentinians as well. Faced with high inflation and rapid losses in purchasing power of the peso currency, Argentinians chose to convert their pesos into dollars for their savings and overseas investments, thus putting a drain on the country’s foreign exchange reserves. In addition, growing debt payments and energy imports further caused central bank reserves to deplete quickly. In an effort to stem capital outflows, Kirchner’s government introduced strict capital controls in 2011, placing tough restrictions on dollar buying. This spurred the growth of a robust black market for dollars, as a lot of Argentinians rushed to purchase dollars on the black market to protect their wealth. The foreign currency controls were eventually lifted by Macri’s government in 2016 to eliminate illegal currency exchanges and to improve Argentina’s ability to attractive foreign capital. In any case, as the supply of pesos grew much faster than the demand under both Kirchner’s and Macri’s governments, the Argentine currency kept drifting lower and lower against the dollar over time. Amid runaway inflation and persistent peso weakness, Argentinians were losing confidence in the local currency. To protect their money, they preferred buying goods or hoarding dollars over holding pesos. This pushed inflation up and drove the peso down even more.

III. Confusing Policy Moves and Loss of Credibility

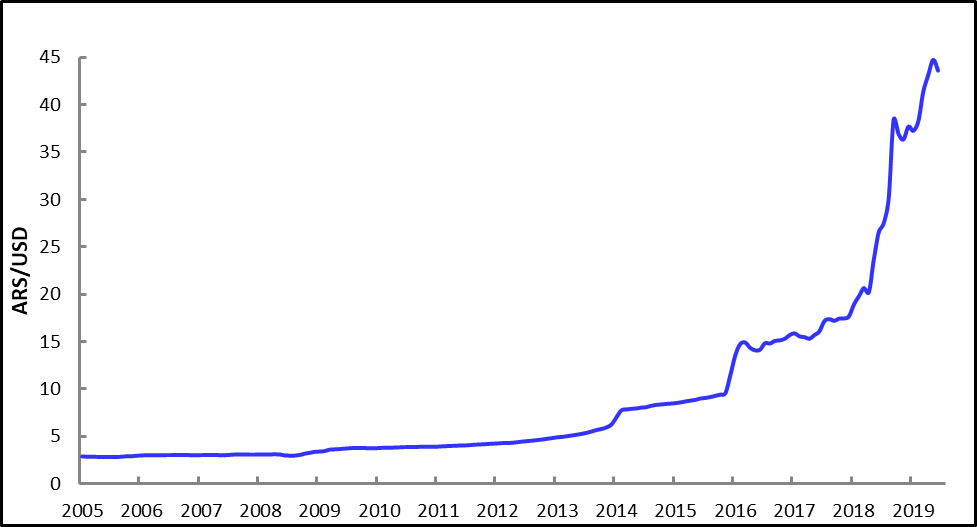

In January 2018, the Argentine central bank shockingly cut its policy rate by 1.5 percentage points to 27.25 % even when inflation expectations were deteriorating fast and actual annual inflation was running at over 20 %. Just a month earlier, the central bank already startled investors by loosening its inflation target for 2018 from 12 % to 15 %. Such confusing policy moves raised serious doubts over the credibility of Argentina’s central bank to tame inflation. This intensified investors’ growing skepticism about the pace and efficacy of the Macri administration’s strategies to combat inflation, cut the fiscal deficit and shore up government finances. With both inflation and government spending kept spiraling out of control, the government was viewed to be too slow to tackle Argentina’s serious structural problems. About 3 months later, many investors appeared to have lost their patience and faith in the Argentine government. It was a huge disappointment that Argentina’s economy remained struggling with spiraling inflation, falling currencies, and mounting debt burden with no end in sight anytime soon. With recession looming, investors were increasingly concerned that Argentina could soon default on its debt obligations. Besides, the surging rates in the U.S. would only add pressure on the peso, making it even harder for Argentina to service dollar debt. The elevated default risks, along with growing fears of further weakness in the peso, prompted foreign investors to pull money out of Argentina’s stocks and bonds. As more and more wary investors fled, currency markets witnessed a large-scale selloff of the peso (see Figure 1).

FRED Database, Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis

Figure 1 Figure 1. The US Dollar (USD) to Argentine Peso (ARS) Exchange Rate in Monthly Averages

In a bid to stabilize the peso and bring inflation under control, the central bank of Argentina raised its policy rate 3 times between April 27 and May 4 by a total of 12.75 percentage points to 40 %. This came after days of heavy market intervention by the central bank to defend the peso. The market intervention operations caused a steep decline in foreign currency reserves at the central bank. The Argentine government quickly sought financing help from the IMF. In June 2018, Argentina secured a 3-year, $50 billion credit line from the IMF to help restore investor confidence. The size of this loan package was the largest ever in the IMF’s history.

Unfortunately, the peso suffered another round of selloff in August 2018. This latest selloff came amid a broad run on emerging-market currencies. With a similar currency crisis unfolding in Turkey, investors’ risk tolerance for emerging-market assets fell sharply. The renewed U.S.-China trade tensions also unnerved financial markets and soured investor risk sentiment. Given Argentina’s excessively high debt, its economy was one of the most vulnerable to financial contagion of emerging-market crises. The peso’s plunge underscored the retreat of foreign capital and put intense pressure on Argentina’s central bank to lift rates much higher.

To prop up the peso, the Argentine central bank promptly raised its policy rate by 5 percentage points to 45 % in mid-August. The rate hike failed to stop the peso from sliding further, nonetheless. Investors grew increasingly doubtful about the commitment and capability of Macri’s government to contain inflation, deficits, and debt at some manageable levels. Indeed, Argentina’s problems were expected to get even worse. The country’s inflation would accelerate due to the falling peso. Argentina’s annual inflation rate went up to 34.4 % in August from 26.4 % following the peso’s big drop in May. As the peso plummeted further in August, Argentina’s foreign debt became much more expensive to service, heightening fears that the country would not be able to meet its debt obligations for 2019. This, in turn, intensified capital flight, thereby exacerbating the peso depreciation pressure.

Investors were thus caught in a negative feedback loop whereby selling led to more selling. On August 29, Macri’s government further rattled investors when announcing that it requested the IMF to speed up disbursement of bailout money. The peso tumbled about 8 % against the dollar to a record low on the announcement. The news was interpreted by the market as a sign that government finances were in desperate shape, deepening concerns about the country’s ability to meet its debt obligations next year. Despite central bank interventions, the peso’s fall continued to escalate during the following day’s trading session. The currency nosedived another 13 % on the day, marking a more than 50 % loss in value since the year’s start. As the peso was in free fall, the Argentine central bank hiked its policy rate sharply by 15 percentage points to 60 % – the world’s highest – on August 30. The central bank also indicated that the rate would not be decreased at least until December.

To ease investor concerns over the government’s ability to cover its finances through 2019, Argentina sought additional financial support from the IMF and got a boost in the country’s credit line to $57 billion – along with faster disbursements of loan funds – in late September. Moreover, as part of a revised agreement with the IMF, the country embarked on a major policy shift by focusing on curbing money supply growth to rein in inflation. Its central bank would target zero monetary base growth until June 2019. Starting in October 2018, Argentina’s central bank would aggressively sell high-interest short-term bills, known as Leliq notes, to local financial institutions through daily auctions to mop up excess peso liquidity from the banking system. The liquidity drain greatly reduced the supply of pesos in circulation and that helped shore up and stabilize the currency. Nonetheless, the central bank’s new policy could provide only temporary relief to the peso.

A more permanent solution would be for the government to bring its fiscal deficit under control. Indeed, many market analysts doubted the sustainability of the new monetary strategy because the tight liquidity squeeze would have very negative effects on the economy. The surge in new issuance of high-yield Leliq notes could not only be costly but also risky because it would saddle the Argentine central bank with excessive debt.

What would come next? Argentina’s economic crisis might not be totally over yet, and the peso could likely remain volatile for the foreseeable future. Argentina’s inflation was expected to go even higher, thanks to a tumbling peso. Its fiscal deficit remained dangerously high, and the government had been too slow to reduce it. With any further rate hikes by the Fed in the U.S., the peso could face renewed selling pressure. If the peso continued to get weaker, Argentina would find it even more difficult to pay its enormous debt. Luckily, the Fed decided to pause the rate hike cycle in January 2019 in light of adverse developments in global economic and financial conditions as well as muted inflation pressures in the U.S. The Fed’s inaction on rates brought Argentina some respite from its currency crisis. Nonetheless, Argentina’s credibility with international investors was badly damaged. The Argentine peso would remain one of the most vulnerable currencies in emerging markets unless the country could get its government finances in order quickly and cut its debt significantly.

IV. An Update for the First Half of 2019

Bring down high inflation appeared too challenging for Argentina. Despite its central bank’s ultra-tight monetary policy stance, Argentina’s inflation rate continued to spike, running at an annual rate of nearly 55 % in March and then over 57 % in May before edging down to just under 56 % in June. The rampant inflation, together with a biting economic recession, was fueling poverty and making life increasingly difficult for Argentinians. In fact, Argentina’s poverty rate already reached 32 % at the end of 2018, up more than 6 percentage points from the year before according to the country’s statistics agency, INDEC. Amid growing discontent over raging inflation, austerity measures, and rising poverty, Macri’s popularity took a big dive.

The strong inflation inertia shown in the data from the first 3 months of 2019 alarmed the Macri’s administration. With his left-wing populist rivals, Alberto Fernández and former President Cristina Kirchner, rising in the polls, there were growing concerns that Macri could lose his reelection bid in October later this year. This prompted Macri to roll out a number of short-term measures in mid-April, aiming at easing price pressures and providing some relief to hard-hit Argentinians. The prices of 60 basic food items would be frozen for at least 6 months. In addition, a freeze was put on the prices of public services such as electricity, gas, and public transportation for the rest of the year. Furthermore, retirees and recipients of government benefits would be offered subsidized credit lines and price discounts – ranging from 10 % to 25 % – at various businesses. Pension agency loans would also be provided to aid pensioners when needed. The government would help out small and mid-size enterprises (SMEs) as well by offering a better payment plan for their taxes. Export taxes for some SMEs could be waived under certain conditions.

The introduction of these voter-wooing measures might be too little too late, however. They were not sufficient to calm investor nerves as political risk soared. Investors increasingly feared that a possible return of a populist, leftist administration would open the door to sovereign default, debt restructuring, and capital control policy again. When a new poll suggested that Kirchner could beat Macri in an election run-off, it triggered a market selloff in late April, with Argentine bonds plummeting and sinking into distressed territory.

Trading in credit-default swaps indicated that the market was pricing a more than 60 % chance of a potential default over the next 5 years. Although Argentina’s economy did poorly under Macri, many investors were worried that a new populist government would do worse. The market selloff showed just how little confidence investors had in Macri’s rivals. As risk aversion intensified, nervous investors pulled money out of Argentina, sending the peso down sharply. The peso fell to a record low of 44.98 ARS per USD in May before recovering somewhat to 42.28 ARS per USD by the end of June.

For the first 6 months of 2019, the peso lost over 11 % of its value against the dollar. The tumbling peso could add to inflation worries, further eroding support for Macri.

V. A Bumpy Ride Ahead

For the remaining half of 2019, political uncertainty is expected to weigh heavily on Argentina’s financial markets, and election developments will likely drive market sentiment and volatility. If investors see an increasing likelihood of a return of a left-wing populist administration, which raises the risk of sovereign default, Argentine bonds and the peso will come under extreme selling pressure. Will Argentina slip into a financial crisis again? Like it or not, that can depend on the outcomes of a hard-to-call presidential election race. Market participants may want to buckle up for a turbulent ride ahead.