Services on Demand

Journal

Article

Indicators

-

Cited by SciELO

Cited by SciELO -

Access statistics

Access statistics

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in

SciELO

Similars in

SciELO -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Apuntes del Cenes

Print version ISSN 0120-3053

Apuntes del Cenes vol.34 no.60 Tunja July/Dec. 2015

Artículo de Investigación

Business across borders between Colombia and Venezuela: from trade to social conflict

Los negocios en la frontera entre Colombia y Venezuela del intercambio comercial a un conflicto social

Os negocios na fronteira entre Colõmbia e Venezuela: da troca comercial ao conflito social

Jhon Antuny Pabón León*

Luz Stella Arenas Pérez**

Magda Zarela Sepúlveda Angarita***

* Administrador de Empresas, Magíster en Gerencia de Empresas. Docente Tiempo Completo de la Universidad Francisco de Paula Santander, Cúcuta, Colombia; Dirección: Avenida Gran Colombia 12E-96, Cúcuta. Correo electrónico: jhonantuny@ufps.edu.co.

** Administradora de Empresas, Magíster en Gerencia de Empresas. Docente Tiempo Completo, de la, Universidad Francisco de Paula Santander, Cúcuta, Colombia; Dirección: Avenida Gran Colombia 12E-96, Cúcuta. Correo electrónico: luzstellaap@ufps.edu.co.

*** Administradora de Empresas, Magíster en Gerencia de Empresas. Docente Tiempo Completo de la Universidad Francisco de Paula Santander, Cúcuta, Colombia; Dirección: Avenida Gran Colombia 12E-96, Cúcuta. Correo electrónico: magdazarelasa@ufps.edu.co.

Fecha de recepción: 14 de septiembre de 2014 Concepto de evaluación: 27 de enero de 2015 Fecha de aprobación: 25 de junio de 2015

Abstract

Border relations in the «living borders» have been an object of study due to the conditions under which the economy of the borders is developed. Investigations carried out between North Santander and Táchira State border are analyzed, comparing them with the principles of the German (the state-nation) and French (the border area) Schools. Studies of the Chamber of Commerce of Cúcuta are analyzed and discussed. It is concluded that the economy of North Santander is affected more by political and ideological positions than by international trade. Governments continue to ignore the reality of two peoples who share a border region, as it is exposed by the principles of the French School.

Keywords: Border relations, living borders, business, nation-state, regional space.

JEL: E65, F16, R10.

Resumen

Las relaciones fronterizas en las «fronteras vivas» tienen interés de estudio dadas las condiciones bajo las cuales se desenvuelve la economía de fronteras. Se analizan investigaciones efectuadas sobre la frontera Norte de Santander y el estado Táchira cotejando con los postulados de las escuelas alemana (el Estado-nación) y la francesa (el espacio fronterizo), se analizan estudios de la Cámara de Comercio de Cúcuta. Se concluye que la economía del Norte de Santander está afectada más por posiciones políticas e ideológicas que por comercio internacional. Los gobiernos siguen desconociendo una realidad de dos pueblos que comparten una región fronteriza tal como lo exponen los postulados de la escuela francesa.

Palabras clave: Relaciones fronterizas, fronteras vivas, negocios, estado-nación, espacio regional.

Resumo

As relações de divisa «fronteiras vivas» tem interesse de estudo devido as condições sob as quais se desenvolve a economia de fronteiras. Analisam-se pesquisas efetuadas sobre a divisa entre Norte de Santander (Colõmbia) e o estado Táchira (Venezuela) cotejando con os postulados das escolas alemãs (o estado-nação) e a francesa (o espaco de fronteira), se analisam estudos da Cãmara de Comercio de Cúcuta. Conclui-se que a economia do Norte de Santander está afetada mais por posições políticas e ideológicas que por comercio internacional. Os governos seguem desconhecendo uma realidade de dois povos que compartilham uma região de fronteira tal como o expõe o postulado da escola francesa.

Palavras-chave: Relacões de divisa, fronteiras vivas, negócios, estado-nação, espaço regional.

INTRODUCTION

Speaking of neighboring countries and regions, inevitably the issue of border arises, a concept that according Grimson (2005, p. 91) has become a key concept in the stories and explanations of contemporary cultural processes. The author indicates that economic or symbolic analysis of so-called globalization refer, again and again, to the limits, the edges, the contact areas; however, he adds that the concept of border remains unclear both in certain diplomatic rhetoric as in much of the social studies and cultural studies. Further, he upholds that just one of its features is the duplicity: border was and is simultaneously an object / concept and a concept / metaphor. On the one hand there seems to be physical, territorial boundaries; on the other, cultural, symbolic boundaries.

Aligned with this reality, it emerges the concept of «living» borders that are nothing more than the group of people who inhabit the border areas of the country, becoming important tool for the exchange and integration with neighboring countries and serving as lookouts of the territorial integrity. It is in these borders, for Wilson and Donnan (cited by Grimson, 2000a), where the tension between legality and illegality is an integral part of everyday life. It's there where commercial transactions between populations are often considered as «smuggling» by States, whereas it is the most natural activity for the locals.

According to the report «Characterization of the Colombian-Venezuelan border,» made by the Andean Community of Nations, which Colombia is part of, this area is «the border area of interest and importance to bilateral relations» and for Andean integration because here it takes place one of the «most intense integration processes at scale of the entire South American continent». Together, Cúcuta (Colombia) and San Cristobal (Venezuela) have 3 million people; 85 percent of young people dominate this universe in an urban population with high geographical mobility.

The research is based in that the border region between North Santander Department and Táchira State has historical ties, which are deeply rooted in its inhabitants. It has complementary economies; families are joined together, study and live on one side or the other of the border. It is made by complex socio-cultural, historical, economic and political relations, turning it in one of the most dynamic borders in Latin America and the one with the largest movement of people and goods between the two countries.

The study and analysis of relations between the two countries is important as it has become one of the most controversial in recent years given the volume of trade especially between North Santander Department in Colombia and the State of Táchira in Venezuela, this attached with the historical, social and commercial relationships that are developed at the border. It is justified to identify strategic positioning between political and economic swings since the economy of the región is influenced by the difficult binational diplomatic relations and economic movement in Venezuela, reflected in the variability of the price of the Venezuelan currency (Bolivar).

Various authors have spoken about the topic, it is quoted: Ardila (2012); Bustamante (2004); Jimenez (2008); Mejia (2009); Plata (2011); Ramirez (2003, 2005, 2008); Ramirez and Cárdenas (2006), Ramirez, Manzano, Zambrano & Nova (2013); Mayora (2012); Ramos (2012); Ramos & Otálvaro (2008); Rodríguez (2012); Sanchez (2011); Taylor (2010); Valero (2008), who have written about the relations between Colombia and Venezuela where cyclically have passed from long periods of estrangement and conflict to moments of cooperation. They analyze reality on the border and allow deepening the historical, social, economic and political study of the subregion to understand the fundamental relationships and economic exchanges, the characteristics of mobility and the establishment of border culture.

One of the most affected cities has been Cúcuta. Therefore, a group of representatives of associations of North Santander that includes various sectors of industry and commerce asked the government to declare an economic emergency in that region, they requested the implementation of measures to cover portfolios of local companies, using the resources of the nation, since they did not receive money from their customers in Venezuela, due to exchange control in that country and the policies implemented in the border area.

The research has a descriptive level, supported by literature review, addressing three aspects: firstthe conceptualization of borders and border relations. Second, information on Colombia-Venezuela relations in the historical, commercial and social context, this was aimed to know the positions of central governments and the most influential economic factors in the border dynamics with an optical nation-state. And finally, the perception of relations between North Santander department in Colombia and the state of Táchira in Venezuela was investigated.

As hypothesis, it is posed that relations in the border region are the postulates of the French school and should not affect socio-economically the border region. The objective of this study is to analyze the business at the border, where the condition of neighboring prevails with all the implications that that means and its social impact, seeking to establish how the ties that bind are influenced by the policies of the governments of Bogota and Caracas and by the ideological positions of the two countries and the mistrust between governments.

The social impact is discussed in the level of employment, the level of informality, victimization and perception, while the economic impact is made with the foreign trade volume, sales and economic perception.

The paper is organized into four parts including the introduction, then it is exposed the concept of borders and synthesis of research on the Colombia-Venezuela relations and the border region of North Santander department (Colombia) and Táchira state (Venezuela). Third, the information and results analysis is shown. Fourth, conclusions are presented and finally the supporting references considered in the study are outlined.

BORDERS

Van Gennep (1986) cited by Grimson (2000b, p. 13-14) considere first territorial boundaries to analyze the metaphorical borders, taking the concept of limit as the core of his theory. He analyzes the rites of passage involved in the border crossing between the two countries as well as the consecration rites that accompany the placement of any markers of political boundaries. When these limits are marked, a particular group appropriates a certain floor space, so that penétrate, being a foreign in the reserved space, is the same as commit a sacrilege.

About this concept, Prieto exposes (2011, p.1) that there are two sides. First, the Germán School which states that the first concept of border was the dividing line that marked the local protection of the manor or the commune; later, with the emergence of the city, and then the nation and the state, that concept became the current one. And second, the French school, which regards man as a geopolitical factor that adapts and meets with the natural elements that surround it. For this school, the border is only an interim framework within which human life unfolds. It is the limiting factor of a people, where the state's relationship with the land is developed; the territory is the basis of the state and the population is living depositary and the very substance of the state. This school studies the border according to the groups that it separates, and its own interests.

This position and the principles of the French School constitute the conceptual framework that will guide this analysis.

In this context it is interesting to analyze the relations between the border cities. Donnan & Grimson (cited by Grimson, 2000a) hold that there is no precise agreement between state and nation since relations between power and identity on the borders and between borders and their respective States are problematic precisely because the state cannot always control the political structures established at its extremities. For these authors as a result, the forces of politics and culture, possibly influenced by international forces of other States, give the borders specific political configurations that make extremely conflicting relations with their governments. Specially, when is posed the event that the regime of cultural borders competes with state borders. First, attention is paid to the government's visión on borders, highlighting the contradictory position between national policies and socio-spatial realities, and it is also noted that the periphery in neighboring territories can possess ignored centrality.

García (1998, p.7) reports that the internationalization brought the opening of geographical borders for incorporating real and symbolic products between nations. It is stated that with globalization, the process deepens and involves a permanent functional interaction of economic and cultural dispersed activities, as well as goods and services generated by a system with many centers, where the speed the goods or services can travel around the world is more important than the geographical positions.

Borders and international business

Borders and international business cannot be demarcated. About this, Daniels, Radebaugh and Sullivan (2004, p. 176-181) report that it is understood as international business all commercial, private or governmental transaction, between two or more countries. Among these transactions there are sales, investment and transport. These international operations of companies and government regulation of international business affect corporate earnings, job security and wages, consumer prices and national security. They also indicate that private companies carry out such transactions for profit and that governments may or may not do the same in their transactions. On trade in goods and services, the authors state that this kind of trade is an important means of linking the countries economically, and that having more links the overall efficiency improves and add that governments routinely influence the flow of imports and exports.

Despite the benefits of free trade, all countries interfere with international trade to varying degrees; this government intervention can be classified as economic or non-economic. It is known that governments intervene in trade to achieve economic, social or political goals. However, it is important to note that governments pursue political arguments when trying to regulate trade. According to Daniels et.al, government officials apply trade policies that, in their opinion, are more likely to benefit the country and its citizens and, in some cases, to their personal political continuity. With reference to the above, they add that in this scenario is observed that the proposals for reform of trade regulations often trigger fierce debates among people and groups who believe they are affected, who are affected more directly (called groups interest) tend to complain more.

In the Latin American case, there are several interesting cases for studying. About that, Grimson (2000b, p.13-14) compiles a series of articles where border relations between various Latin American countries and their cultural, social and economic implications are discussed.

Relations between Colombia and Venezuela

In the Latin American context when studying the relations between Colombia and Venezuela, Ramírez (2003, p.203) said that security problems have periodically disturbed relations between Colombia and Venezuela, which have passed cyclically from long periods of estrangement and conflict to times of cooperation. In his study, he indicates that while the first corresponded to tensions over border demarcation, accumulation of unresolved issues and paralysis of mechanisms for dialogue and negotiation, the latter have taken shape once the most algid joints are exceeded in border, allowing a recovery of the other elements of the relationship. Ramirez also said that these moments are so short that they are not able to consolidate a core set of proactive management agreements between their countries that is irremovable, either if there are problems or disagreements on the border and/or between the capitals, or the government or governing party changes in either country.

About that, Mejía (2009, p.7) notes that historically, the political relations between Colombia and Venezuela have ranged on the one hand between the voltage generated by the identification and border control, the overflow of the Colombian conflict, the government and ideological configuration models the perception towards the integration processes; and cooperation embodied in binational infrastructure projects, growing and constant flows of trade, and dynamics of the border in the social and economic level.

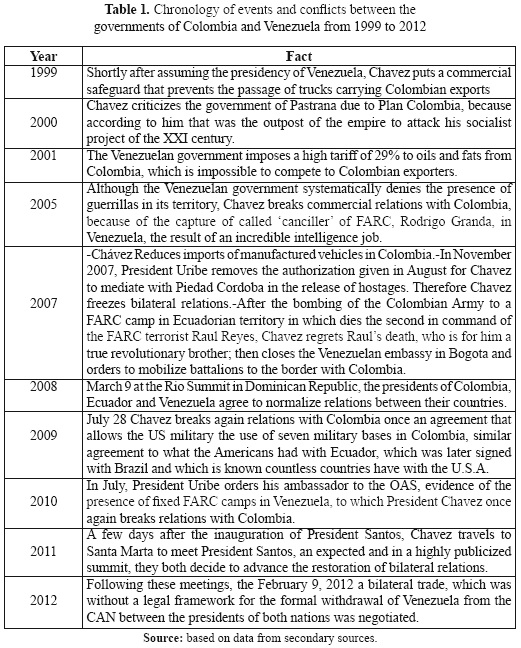

In response to the conflicts that have arisen between the two countries, Plata (2011) stated that it certainly pleases everyone that two country neighbors restore diplomatic relations, but it is an issue that must be seen carefully; and he made a brief chronology of the high lights of the enmity between the Colombian and Venezuelan governments and why today we speak of improving relations, the facts:

When he was asked about economy and trade between the two countries, Mayora (2012) analyzed the «Effects of exchange controls in trade with Colombia. The consequences of the withdrawal of Venezuela from the Andean Community». He examined the causes that led to boost bilateral trade, maximum and sharp drops but in one way or otherwise is needed for its complement. He states that these events are related to the rigors of exchange control in Venezuela called CADIVI that affect the price of the products which are recorded daily in various transactions carried out by traders and marketers recorded on the Colombian side and by the end of 2011 there was an exchange of 2.193 million dollars.

It is noteworthy that the two countries had a trade of more than US $ 6,000 million in 2008. Such dynamics fell to US $ 4050 million in 2009 and then to US $ 1,423 million in 2010 due to political disputes between the two nations. Díaz (2012, p.1). Despite the problems of default that occurred, Colombia made exports to Venezuela for US $ 1,553 million in 2011, showing a slight recovery compared to 2010. Venezuela became the second largest trading partner of Colombia, after the United States, but the withdrawal of the Andean Community and subsequent rupture of relations, between 2009 and 2010, during the second term of former Colombian President Alvaro Uribe (2002-2010), led to a collapse of trade between the two countries.

Border integration zones

On bilateral relations, Ramírez (2005), in «The Crossroads of integration: the case of the Colombian-Venezuelan border,» assumes a differentiation of the áreas of the five Colombian land borders not from the political-administrative divisions as it is done but of routine, cultural, educational, economic, political and security environment interactions that throughout history have shaped various areas and have determined both its problems and great opportunities for neighborly way. The most important area is North Santander-Táchira, which have been consolidated as an example of border regional economy. Economic integration in this border is such that, it is reflected in all aspects of their daily lives. One example is that «when services are better in Venezuela, or the bolivar falls, the trade tide goes from Táchira to Cúcuta; and when services improve in Colombia or the weight vanishes, it is Táchira who moves to Cúcuta due to the same commercial benefits and services.»

For Ramírez (2008), «Border Integration Zones of the Andean Community. Comparing their scope», border areas involving territories of two or more countries have always been subject to continuous more or less spontaneous reconfigurations, unlike the boundary lines marked by milestones and landmarks. They have not been directly induced or recognized by states, because they arise according to local interactions. Since the beginning of the century, a process of definition of border áreas from the Andean community policy on border development and integration has been started, but the results have been contradictory. While such definitions contain conceptual advances, they seem disjointed of the debate about the meaning of the border areas in the integration between neighbors to face globalization, and its application has not leaded to border processes yet.

Meanwhile Ramos (2012) introduces common and existing differentiators between Colombia and Venezuela in order to contextualize the current dynamics that feed the binational relationship. He discusses the existence of some economic phenomena that distort the relationship and that are being exploited by new illegal groups in the border area and shows how drug trafficking and lawlessness have dented security and institutions of the two countries. The phenomenon of the flow of Venezuelans who are immigrating to Colombia and its potential impact is analyzed.

METHOD

The research was conducted at a descriptive level, supported by literature review addressing three aspects: the conceptualization of borders and border relations, Colombia-Venezuela relations in the historical, commercial and social context, this was intended to know the positions of central governments and the most influential in the border dynamics with an optical nation-state and finally it was investigated the perception of relations between North Santander department in Colombia and the state of Táchira in Venezuela in economic factors. That point was based on perception and economic situation surveys published by the Chamber of Commerce of Cúcuta and statements of union representatives and the opinion of industry, politicians and academics. After reviewing the work and analyzing the border reality, it is compared with theoretical postulates on «borders» to make findings of research.

ANALYSIS OF INFORMATION AND RESULTS

- Border relations

The investigation shows that the Colombia-Venezuela relations have been more marked by political and ideological positions of the central position than by economic and commercial positions. For the researcher, it is current today Núñez's position (2009), who said that «the Venezuelan nationalism, anti-Colombian roots, and anti-imperialism are the two sources where Hugo Chavez drinks ideologically. Both inheritances inevitably lead him to face the Colombia of Alvaro Uribe. Thanks to his Venezuelan nationalism, he always keeps a suspicious eye on his neighbor». Despite they were made in 2009, and the actors changed Juan Manuel Santos and Nicolas Maduro, new frictions between the two leaders have been made, frictions where the background remains ideological.

It has been determined that the actual effects of the rupture of relations between the two countries depend on additional measures applied by the countries involved. Among them: the suspension of trade relations, the restriction and/or suspension of movement of people, prohibition and/or restriction of imports.

This has meant that the distance between Venezuela and Colombia have been suffered mostly by border people which are experiencing a strong impact due to strong ties that exist in these areas due to no decisions concerning to the closure of consular activities between Caracas and Bogota were taken.

The analysis of conflicts from 2005 to the present, confirms a clear ideological political content in the history of encounters between the governments of the two countries and it is not observed to be aligned with this theory of international business. According to Daniels, Radebaugh and Sullivan (2004, p. 176-181), among the arguments for government intervention in business are: to create domestic employment, infant industries, promote industrialization, encourage inward investment. While export restrictions can increase prices worldwide, it would lead to require more controls to prevent smuggling, to the substitution, hold down domestic prices by increasing domestic production, shift production and sales abroad; by the other hand, the import restrictions may prevent the dumping to take the domestic producers out of the business, get other countries to remove restrictions and make foreign producers to lower their prices.

In the case of Colombia and Venezuela, it has not been sought any of these formulas as the two economies are complementary and feed each other, and have common strategic areas such as the energy area and trade corridors to the Pacific. At the level of the border area in the past and up to now, the relationship between Venezuelans and Colombians have been left out of the diplomatic disagreements, it has been cordial and forged a binational culture.

socio-economic indicators in the border region

In reviewing the document Ramírez, Manzano, Zambrano and Nova (2013), where economic and social structure of Norte de Santander is analyzed for the period between 2000 and 2010, the weakness of North Santander economy stands out due to underdeveloped industrial sector. Added to this, social record shows that the Department made progress in education coverage and poverty reduction, according to the DANE in 2011 30.43% of North Santander is unable to meet basic needs and 11% is in terms of poverty. Although poverty levels are above the national average and in terms of severity of extreme poverty, its capital is second among the seven major metropolitan areas of Colombia. In human development there is a progress which is a product of improvements in educational attainment, the greatest achievement is in the basic secondary and high school, which between 2002 and 2010 extended the registration enrollments to 45.4% for elementary school and 53.3% for secondary school, but when inequality and violence is discounted, the human development índex deteriorates significantly.

According to information consulted in the database of the Chamber of Commerce of Cúcuta, the Metropolitan Area of Cúcuta (MAC) in January 2014 recorded an unemployment rate of around 16.7%, a figure that stood at the border as the second city of the country with the highest unemployment, while the national rate registered an 11.01%.

The workforce of the MAC is mainly generated by 39% in trade, hotel and restaurant sector, 21% is formed in community, social and service; and manufacturing services contributes 14%. Labor informality in the MAC represents to the border a rate that has not improved and seems stuck in time. In the quarter July-September/2014, it was 71.4% and in the same period 2013 the rate was 70.4%.

Foreign trade in September 2014, the accumulated value to most foreign markets sold USD 201.2 million. While in the same period of 2013, sales were $ 319.9 million, representing a decrease of 37% that means $ 119 million. Sales to Venezuela have declined by 63% over the period of 2013 - from USD 100.5 million sold in September 2013 to USD 37.3 million dollars in 2014. Today Venezuela is not the first export destination; it is the former market leader. Now the positions are the US, China and then Venezuela.

In reviewing the results of inflation in 2013, the consumer price index for the border marked 0.56% (year to date).

Cúcuta was one of the cheapest cities in the country, which favored local consumption. In 2014 the rate was at 3.01%, it means 2.56 percentage points above the last record, because the local consumption is demanding more local products, as a result of tight control of subsidized from neighboring country Venezuela.

There is also an exchange differential that makes border marketing products very attractive to the market of Cúcuta and its metropolitan area. It is estimated that 40% of Venezuelan products vanish in the porous borderline and it is calculated USD 3,600 million annually by smuggling to Colombia.

The economic models of the two countries tend to create this type of market asymmetries and lead to imbalance in products and prices that they are used by a natural market variable called smuggling. The measure itself has protectionist nature of the Venezuelan economy.

Results of Venezuela, where they face a different economic model called by some socialist and by some others communism, in 2013 were:

High inflation, rampant shortages, low international reserves, greater controls, the presence of four types of exchanges (including three ofncials), millionaire debts with the productive sectors.

Inflation: Between April 2013 and February 2014, according to the latest data from the BCV, the accumulated inflation reached 43.5%. Inflation last year closed at 56.2%, the highest in Latin America and the highest recorded in Venezuela since 1996. The food category is the one that has risen, with rise of 74.5%, the highest in Latin America, according to FAO data.

Shortage: This index stood at 28% in January 2014, a record registered by the BCV. Since July 2013, the indicator has risen steadily. Delays in the allocation of foreign currency and smuggling determine a permanent shortage of products, which affects one in four commodities.

The economy suffered a sharp slowdown, going from growth of 5.6% in 2012 to a modest 1.6% in 2013, well below the 6% expected by the government.

Foreign exchange reserves fell 29% during 2013, from 29.750 million to 21.251 million.

Oil and its derivatives, whose marketing is State monopoly, in 2013 contributed 94% of the Venezuelan currency and generated 64.693 million dollars that are managed and administered by the State thanks to exchange controls operative since 2003.

Subsidies for petrol and basic food, along with the exchange difference of 10 to one among the official market rate for food imports and the parallel market, feed a huge smuggling to neighboring countries, mostly Colombia.

In the state of Táchira, according to the National Statistics Institute of Venezuela (NSIV), the unemployment rate was 3.6% in 2009, in 2010 3.2%, in 2011 was 2.7% and in 2012 was 3.6%. But in the research it was found that there is no consensus about the veracity of these figures in Venezuela since the NSIV (INE, in Spanish) measures the occupancy rate but not the employment rate. This differs from the methodology used in Colombia and makes unemployment figures are not comparable.

Figures for informality, it was found in INE reports that in 2009 reached 55.0%; in 2010 it was 52.9%; for 2011 51.2%; in 2012 49.5% and in 2013 49.4%. Regarding production figures and added value no detailed information for Táchira state was found.

The comparison of these results demonstrates the economic and social distortions that occur in the border region. About border policies, the Venezuelan government took temporary closures strategy of international bridges Simón Bolívar and Francisco de Paula Santander, the action was stemmed from the shortage generated by the extraction of consumer goods and fuel to the border and the difficulty of domestic production, including the import of raw material for the production of basic consumer goods.

Given this reality, Colombian side response has been to give an economic and commercial connotation, impacting socially the region in its indicators, making an appeal to the government to declare an economic emergency.

While on the Venezuelan side, the response has been purely political. They have affirmed the existence of an «economic war» against the system and posed repression and criminalization of commercial activity in the border region as solutions, militarizing the border and «building walls», ignoring calls to rectify that several Venezuelan sectors have made, especially economic and commercial sector of state of Táchira, which have been quite affected; and the general population has been more affected for the limited supply of the components of the food basic basket as well as economic and financial organizations abroad who have been disqualified in their intention.

In research, statements were found in the Venezuelan press spokesmen of regional Chamber of Commerce of San Antonio and Fedecamaras, who demand to be taken into account in addressing the problems of the border region.

It is outlined in the article «Unemployment has contributed smuggling also» published in Diario de Los Andes on September 1 (2014), that given the short supply of jobs in Táchira, in recent years people have taken on in practice of illegal activities such as smuggling in its various forms (food, medicine, technological equipment, fuel, etc.), as a means to survive. According to public inquiry, in recent years due to the economic recession and the closure of businesses in the state, the unemployment figures have soared. leading citizens to engage immediately in any activity, whether it is legal or not, for this find it lucrative and solves their basic needs.

Likewise, the situation has been classified by the president of the Chamber of Commerce of Ureña, Isidoro Teres, very serious, a total mess. He explained that the border axis faces three different fronts. On the Venezuelan side, protests against the national government; while on the Colombian side, people engaged in smuggling extraction express their dissatisfaction with the controls; and there is the National Guard.

This has resulted in an increase in the usual shortages in the area, which already reaches alarm levels of shortage and the population in general is alarmed. There is said the biggest concern is the lack of pharmaceuticals. «In these times of protest and confrontation is worrying that we do not have even sutures to help those who might be injured. See «Municipalities of Táchira lack of food, fuel and medicine» article of Journal de Los Andes, February 26, 2014.

In this respect a difference of opinion on those involved in the smuggling of extraction is observed. By delving into the issue it was found evidence that supports that smuggling extraction actors from both countries are involved, even points to the existence of binational mafias.

Victimization and perception in the border area

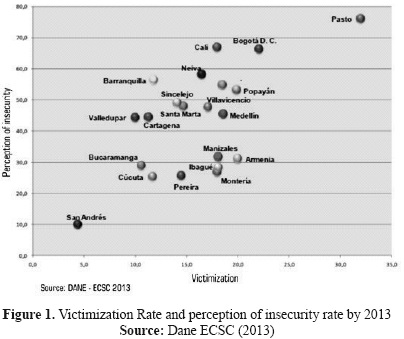

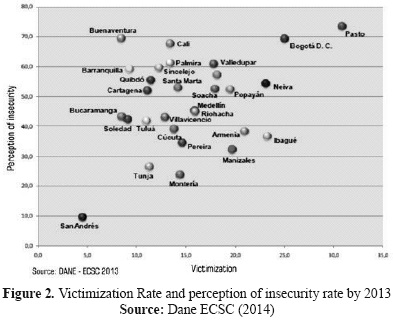

It was inquired about the levels of victimization and perception in North Santander to try to observe any relationship between the socio-economic impact and levels of victimization, it is clarified that no statistical correlation analysis between variables was performed, only an observation of the figures was made in the datábase of the DANE in the Survey of Citizen Security (ECSC in Spanish) by 2013 and 2014, (the data is consolidated in the capital city of the department). See Figure 1.

In 2013 the city of Cúcuta, showed a victimization rate of 11.7% below the national average that was 18.5%; while the perception of insecurity in that year was 25.3% compared with 54 8% nationally. Figure 2 shows the result of 2014.

It was verified that in 2014 in Cúcuta the level of victimization was 13.8%, against 18.2% nationally and it was found that perception of insecurity was 22% versus 25.3% nationally.

Compared to the previous year it was verified that there was an increase in the level of victimization in Cúcuta, going from 11.7% to 13.8%, while nationally decreased 18.5% to 18.2%. Regarding the level of perceived insecurity in Cúcuta, it decreased 25.3% to 22% while national decreased significantly from 54.8% to 25.3%.

The results could show that there is some indication of a relationship between increasing levels of victimization and deterioration social indicators of unemployment and informality, in North Santander Department, but this is not ensured as it was not subject to statistical analysis.

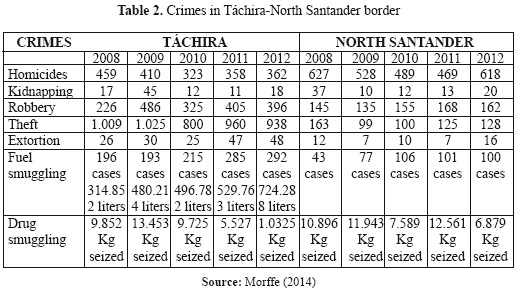

Morffe was found (2014), who presented statistics on crimes that occurred in state of Táchira (Venezuela) and North Santander department. See Table 2.

The murders in Táchira and North Santander in 2009 revealed that 528 murders occurred in North Santander, a figure that rose to 618 deaths for this offense in 2012. In the case of Táchira, 410 murders occurred in 2009 and the figure for this offense declined to 362 deaths for this offense in 2012.

It is determined that the Venezuelan side of the fuel smuggling crimes and drug smuggling are the most rebounded between 2008 and 2012. The result confirms previous statements about the activity shifted to smuggling as a way out of crisis unemployment.

Economic perception regiónin the border

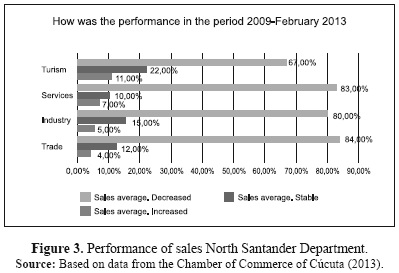

Based on the foregoing, the surveys for the years 2009, 2011, 2012 and February 2013 published by the Chamber of Commerce of Cúcuta were analyzed; the study covered the sectors trade, industry, tourism and services. The economic perception research was conducted by running 500 surveys distributed in different parts of the city. The sample of selected companies was established through the records obtained at the Chamber of Commerce of Cúcuta. The design of the survey contained a questionnaire prepared by the Economic Observatory of the Chamber of Commerce of Cúcuta. Three of the questions presented which relate to border problems were studied, these were: sales performance, identifying variables that affected businesses and the impact of the border crisis in companies. The analysis of the surveys showed that in the period sales fell in all sectors, as shown in Figure 3.

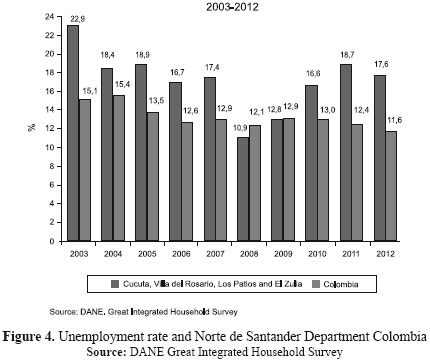

On average, 78.5% stated that sales declined, 1 4. 75% that they were maintained; and 6.75% that they rose. It was found that 67% of tourism sector respondents indicated that the sales declined; in the service sector, 83% of respondents replied that there was a decrease in sales; for the industrial sector the decrease was by 80% and for the trade sector by 84%. The drop in sales was reflected in rising unemployment and falling participation of North Santander Department (NSD) in the Gross Domestic Product (GDP) as evidenced in Figure 4 corresponding to the unemployment rate in NDS and country.

Unemployment

North Santander recorded an unemployment late of 12.4%, higher than in 2010 and 2011 by 0.6 percentage points and 0.2 percentage points respectively in 2012. See Figure 4.

It is observed that the rate of unemployment in North Santander is above the national average and that percentage has been increasing since 2008. It is considered as a consequence of the economic crisis due to conflicts between central governments of both countries, which have affected the border region.

GDP

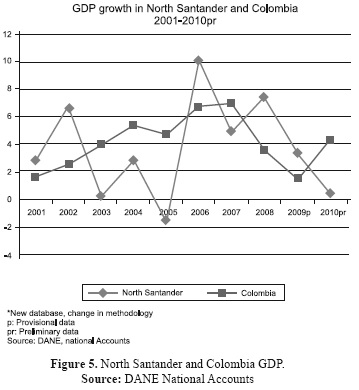

GDP behavior is shown in Figure 5.

Gross domestic product (GDP) measures the level of productive activity and behavior, evolution and economic structure. During the period 2007-2011 GDP performance in North Santander presented positive rates. In 2011 it presented a growth rate of 2.6%; the lowest growth rate was in 2010 (0.8%), while the highest in the period was recorded in 2008 (7.2%). In North Santander, fluctuations were more pronounced with peaks in 2006 (11.0%) and 2008 (7.2%), and had low growth in 2005 (0.4%) and 2010 (0.8%). The trend of production growth in North Santander tends to be opposed against the national.

Variables that influenced the management of companies according to assigned importance

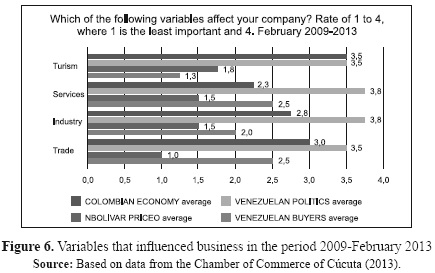

The opinion of respondents on the variables that influenced businesses was also analyzed, see Figure 6:

It was determined that the Bolívar price was the most important variable, averaging 1.4 on the scale where 1 is assigned to the most important and 4 is considered the least important; Second, Venezuelan buyers with an average of 2.1; third, the Colombian economy with 2.9 and finally, 3.6 Venezuelan politics.

These results show how the dependent variables of the border relationship affect the performance and management of companies in North Santander, which shows the complex interplay that, occurs in the area of border integration.

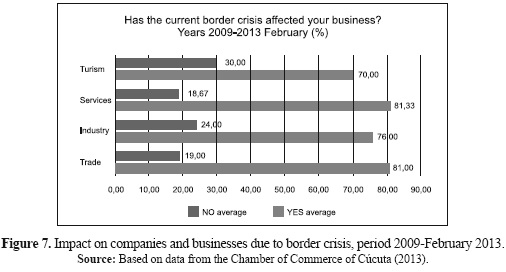

Border crisis impact on companies and businesses

Figure 7 shows the results of the consultation on the border crisis impact on companies and businesses.

It was evident that all sectors stated that the border crisis did impact on business, 77.08% of respondents said that they were affected and 22.92% said they were not. The trade sector and the service sector showed the highest percentage of affirmative responses, about 81% said yes. While the tourism sector and the commercial sector responded with 70% and 76% respectively.

CONCLUSIONS

Relations between Colombia and Venezuela have been marked by periods of «love and hate», as expressed by several writers and researchers when studying the border, which is considered «the most alive border» in Latin America. Throughout history it has elapsed between agreements and crises which have prevailed over the political and ideological theories and postulates of international trade, where different strategic visions of the governments of each country have dominated the scene; and trade relations have been affected regardless of a reality that exists at the crossroads border of the two states.

The analysis of socio-economic indicators shows the impact that occurred in North Santander with rising unemployment, increasing informality, the fall in foreign trade, and falling sales as a result of political conflicts between the two countries, and increased with the policies of the Venezuelan government, the increase in smuggling by the existing exchange rate differential.

While the Venezuelan, the crisis is shown by increased commodity shortages, high inflation that reduces the purchasing power, joint with the repression and criminalization of business. Add to that, the shortage of foreign exchange for control of change that is affecting firms in San Antonio and Ureña has led to the closure of a large number of them.

In analyzing the survey of economic perception conducted by the Chamber of Commerce of Cúcuta, it was noted that due to conflicts and crises between central government, sales fell in all sectors of the economy. In identifying variables that affected companies, it was determined that the price of Bolivar and the presence of Venezuelan buyers were the most influential variables, while the Colombian economy and the Venezuelan politics were not deemed as the most critical factors, it is not perceived that the decisions of the nation state are those that most affect the border region as well as the transit of people and the value of the currency at the border.

Respondents perceived reluctance of national governments to address the border realities and added that there is a disconnection with border issues. It is considered that there is a centralized development model that ignores local issues and only gives a macroeconomic approach to a reality that affects supply of the population of both countries sector.

This was corroborated by the statements of representatives of the productive sectors, who have asked the central government to the declaration of economic emergency in North Santander to mitigate the impact of the border crisis since the supposed benefits of the Free Trade Agreement (FTAs) and even signing bridge trade agreements as the last signed with Venezuela did not reflect ñor have reflected an improvement in economic conditions in the North Santander.

It is important to rescue here the conclusions of Jiménez (2008, p. 271-272) which remain current by the time of this research, among others he states: that the binational problems acquire a connotation of international border crisis effect due to the oversizing of information given by the national and local media. In this context, border actors amid diplomatic tensions are affected by a climate of uncertainty and fear of the uncertain contingencies of border trade. Given the climate of impositions and restrictions, delays and end points of arrival in the binational border trade, entrepreneurs and traders accumulate knowledge and experience and adapt to an uncertain and changing business environment. Thus, trade actors and institutions develop contingency plans and business strategies to suit the changing environment. Despite the perception people have about a restricted commercial stage, local initiatives at policy and institutional level to reset the current conditions are not visible and concrete, except for some Venezuelan initiatives that have failed within a scenario with higher restriction and control. Respondents actors do not relate turning points of the diplomatic crisis with commercial crisis; instead, they identify other critical points in the economic cycle, or have a vague perception of the impact of the diplomatic tensions, despite acknowledging predominantly in the Venezuelan case, a climate of restrictions and gaps in the existing business regulations, legal uncertainty, indifference, lack of knowledge and lack of local autonomy from the central state.

The application areas of integration, as support for living borders between the two countries, find many barriers since the support of the central government to local and regional active forces is not guaranteed by traditional conceptions of border handled; on the one hand the management and control by the state of border areas, aimed at defending the territory and national sovereignty and on the other hand promote the development and improvement of the quality of life for residents in border communities.

In the border area there is a growing conflict which is manifested by repeated demonstrations in the border bridges to protest the measures taken, which affect the population that is engaged in commercial activity in the border either legally or illegally. The boom of San Antonio and Ureña industrial potential disappeared. Trade shows very low activity while industries based in Ureña are only memories.

It is concluded that the posed hypothesis «relations in the border region follow the postulates of the French school and should not affect socio-economically the border region between North Santander (Colombia) and the state of Táchira, Venezuela», it is not meet and instead prevails the notion of state-region. The clash of the two schools and approaches on border studies are evidenced in this region. By one hand the state-region where central governments, especially the one in Venezuela, have emphasized the theory of boundary lines, ignoring the cultural, historical and social reality existing in this area of development and integration, just as it is exposed by the theory of border area.

REFERENCES

1. Ardila, M. (2012, enero-julio). Relaciones colombo-venezolanas. Una cooperación vacilante entre potencias regionales secundarias. Cuadernos sobre Relaciones Internacionales, Regionalismo y Desarrollo, 7(13). Recuperado de http://www.saber.ula.ve/bitstream/123456789/36433/1/articulo4.pdf. [ Links ]

2. Bustamante, A. (2004, enero). Subnacionalismo en la frontera. Caso de Táchira (Venezuela)-Norte de Santander (Colombia). Territorios, (11), 127-144. Recuperado de http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=35701107. [ Links ]

3. Cámara de Comercio de Cúcuta. (2013). Encuesta de percepción económica. Recuperado de http://www.dataCúcuta.com/#!estudios/cur7. [ Links ]

4. Departamento Administrativo Nacional de Estadística -DANE- (2013). Encuesta de Convivencia y Seguridad Ciudadana. Recuperado de https://www.dane.gov.co/files/investigaciones/poblacion/convivencia/2013/ECSC_Cúcuta.pdf. [ Links ]

5. Departamento Administrativo Nacional de Estadística -DANE- (2014). Encuesta de Convivencia y Seguridad Ciudadana. Recuperado de https://www.dane.gov.co/files/investigaciones/poblacion/convivencia/2014/ECSC_Cúcuta.pdf. [ Links ]

6. Daniels, J., Radebaugh, L. & Sullivan, D. (2004). Negocios internacionales. México: Pearson Educación. [ Links ]

7. Díaz, G. (2012, 9 de febrero). Colombia y Venezuela concluyen negociaciones comerciales. El País. Recuperado de http://www.elpais.com.co/elpais/economia/noticias/colombia-y-venezuela-concluyen-negociaciones-comerciales. [ Links ]

8. García, E. (1998). Prólogo. En E. García (Comp.). Fronteras: espacios de encuentros y transgresiones (p.7). San José, Costa Rica: Universidad de Costa Rica. [ Links ]

9. Grimson, A. (2000a). Fronteras naciones e identidades. La periferia como centro. Buenos Aires: Ciccus-La Crujía. [ Links ]

10. Grimson, A. (2000b, nov-dic). Pensar fronteras desde las fronteras. Nueva Sociedad, (170). Recuperado de http://www.nuso.org/revista.php?n=170. [ Links ]

11. Grimson, A (2005).Fronteras e identificaciones nacionales: diálogos desde el Cono Sur. Nueva época, 5(17), 91. Recuperado de http://www.jstor.org/stable/41675677. [ Links ]

12. Jiménez, C. (2008, dic.). La frontera colombo-venezolana: una sola región en una encrucijada entre dos estados. Reflexión Política, 258-272. [ Links ]

13. Mayora, H. (2012, jul-dic). Efectos del control de cambio en el intercambio comercial con Colombia. Consecuencias del retiro de Venezuela de la Comunidad Andina. Revista Venezolana de Análisis de Coyuntura, 18(2), 93-101. [ Links ]

14. Mejía, A. (2009). Análisis de la incidencia de las tensiones políticas entre los gobiernos de Colombia y Venezuela en el comercio binacional durante el período 2005-2008. Monografía, Universidad Colegio Mayor de Nuestra Señora del Rosario, Facultad de Relaciones Internacionales, Bogotá [ Links ].

15. Morffe, M. (2014). El riesgo percibido sobre la seguridad ciudadana en la frontera Táchira-Norte de Santander. Recuperado de http://es.slideshare.net/miguelmorffe/lminas-defensa-teg-riesgo-percibido-sobre-la-seguridad-ciudadana-en-la-frontera-tchiranorte-de-santander. [ Links ]

16. Núñez, R. (2009, 21 de agosto). Colombia, Venezuela: entre el amor y el odio. Recuperado de http://www.180latitudes.org/analisis/entre-el-amor-y-el-odio.html. [ Links ]

17. Plata, M. (2011, 5 de nov.). Restablecimiento de relaciones Colombia-Venezuela. Recuperado de http://sinfronterasnews.com/columnistas/625.html. [ Links ]

18. Prieto, E. (2011, 15 de enero). Las fronteras. Recuperado de http://www.prietosilva.com/Las%20fronteras.htm. [ Links ]

19. Ramírez, J., Manzano, D., Zambrano, M. & Nova, E. (2013, abril). ¿Por qué no le va "tan bien" a la economía de Norte de Santander? Observatorio Socioeconómico Regional de Frontera OSREF, (1), 1-50. [ Links ]

20. Ramírez, S. (2003). Colombia-Venezuela: entre episodios de cooperación y predominio del conflicto. En J. Domínguez (comp.), Conflictos territoriales y democracia en América Latina, (pp. 203-272). Buenos Aires: Siglo XXI , Flacso Chile Universidad de Belgrano. [ Links ]

21. Ramírez, S. (2005). Las encrucijadas de la integración: el caso de la frontera colombo-venezolana. En Convenio Andrés Bello (coord.), Siete cátedras para la integración, (pp. 67-128). Bogotá: Universidad Nacional de Colombia, Cátedra Andrés Bello. [ Links ]

22. Ramírez, S. (2008, enero-junio). Las Zonas de Integración Fronteriza de la Comunidad Andina. Comparación de sus alcances. Estudios Políticos, (32), 135-169. [ Links ]

23. Ramírez, S. (2011). Obras publicadas. Recuperado de http://socorroramirez.50webs.com/hoja.htm. [ Links ]

24. Ramírez, S. & Cadenas, J. (Coord.). (2006). Colombia-Venezuela: retos de la convivencia. Bogotá: Universidad Nacional de Colombia, Instituto de Estudios Políticos y Relaciones Internacionales, Universidad Central de Venezuela, Centro de Estudios de América. 416p. [ Links ]

25. Ramos, F. (2012, enero-junio). Colombia y Venezuela: la necesidad de reestructurar una compleja relación. Cuadernos sobre Relaciones Internacionales, Regionalismo y Desarrollo, 7(13), 1-27. [ Links ]

26. Ramos, F. & Otálvaro, A. (2008). Vecindad sin límites. Encuentro fronterizo colombo-venezolano, Zona de Integración Fronteriza entre el departamento de Norte de Santander y el estado Táchira. Bogotá: Facultades de Ciencia Política y Gobierno y de Relaciones Internacionales, Centro de Estudios Políticos e Internacionales CEPI, Editorial Universidad del Rosario. 130 p. [ Links ]

27. Rodríguez, M. (2012). Análisis de las tensiones diplomáticas entre Venezuela y Colombia y su incidencia para el comercio binacional entre Táchira y Norte de Santander durante el periodo 2007 a 2010. Monografía. Universidad Colegio Mayor de Nuestra Señora del Rosario, Facultad de Relaciones Internacionales, Bogotá. 66p. [ Links ]

28. Sánchez, F. (2011). La Frontera Táchira (Venezuela) - Norte de Santander (Colombia) en las relaciones binacionales y en la integración regional. Si Somos Americanos, Revista de Estudios Transfronterizos, 11(1), 63-84. [ Links ]

29. Taylor, C. (2010). El rol de las instituciones internacionales en el mantenimiento del comercio bilateral entre Venezuela de Hugo Chávez y Colombia de Álvaro Uribe. Revista de Ciencia Política, (10). Recuperado de http://www.revcienciapolitica.com.ar/num10art4. [ Links ]

30. Valero, M. (2008). Ciudades Transfronterizas e interdependencia comercial, en la frontera Venezuela-Colombia, (pp. 67-96). En H. Dilla (Coord.). Ciudades en la frontera: Santo Domingo: Manatí [ Links ].