Services on Demand

Journal

Article

Indicators

-

Cited by SciELO

Cited by SciELO -

Access statistics

Access statistics

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in

SciELO

Similars in

SciELO -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Colombian Journal of Anestesiology

Print version ISSN 0120-3347

Rev. colomb. anestesiol. vol.43 no.1 Bogotá Jan./Mar. 2015

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rcae.2014.11.004

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.rcae.2014.11.004

Guidelines and consensus

Evidence-based clinical practice manual: Patient preparation for surgery and transfer to the operating room*

Manual de práctica clínica basado en la evidencia: preparación del paciente para el acto quirúrgico y traslado al quirófano

David A. Rincón-Valenzuélaa,*, Bibiana Escobarb

a Anaesthetist, Master in Clinical Epidemiology, Professor of Anaesthesia, Universidad Nacional de Colombia; Anaesthetist, Clínica Universitaria Colombia, Bogotá, Colombia

b Anaesthetist, PhD in Medical Science, Professor of Anaesthesia, Universidad Nacional de Colombia, Instituto Nacional de Cancerología, Bogotá, Colombia

Corresponding author: CI 23B 66-46 Consultorio 403, Bogotá, Colombia. E-mail address: darinconv@unal.edu.co (D.A. Rincón-Valenzuela).

*Please cite this article as: Rincón-Valenzuela DA, Escobar B. Manual de práctica clínica basado en la evidencia: preparación del paciente para el acto quirúrgico y traslado al quirófano. Rev Colomb Anestesiol. 2015;43:32-50.

Article info

Article history: Received 8 October 2014- Accepted 25 October 2014

Abstract

Introduction: Patient preparation for surgery and transfer to the operating room are two priority processes defined within the procedures and conditions for authorization of health care services by the Ministry of Social Protection in Colombia.

Objectives: The aim of this initiative was to develop a manual of clinical management based on the evidence on patient preparation for surgery and transfer to the operating room. Materials and methods: A process divided into four phases (conformation of the development group, systematic review of secondary literature, participatory consensus method, and preparation and writing of the final document) was performed. Each of the standardized techniques and procedures is used to develop evidence-based manuals. Results: Evidence-based recommendations on pre-anaesthetic assessment, preoperative management of medical conditions, education and patient communication, informed consent, patient transfer to the surgical area, surgical site marking, strategies for infection prevention and checklist were performed.

Conclusion: It is expected that with the use of this manual the incidence of events that produce morbidity and mortality in patients undergoing surgical procedures will be minimized.

Keywords: Operating Rooms, Evidence-Based Medicine, Anesthesia Surgical Wound Infection, Checklist.

Resumen

Introducción: La preparación del paciente para el acto quirúrgico y el traslado del paciente al Quirófano son 2 procesos prioritarios definidos dentro de los procedimientos y condiciones de habilitación de servicios de salud por parte del Ministerio de Salud y la Protección Socialen Colombia.

Objetivos: El objetivo de esta iniciativa fue desarrollar un manual de manejo clínico basado en la evidencia sobre la preparación del paciente para el acto quirúrgico y traslado al quirófano.

Materiales y métodos: Se realizó un proceso dividido en 4 fases (conformación del grupo elaborador, revisión sistemática de literatura secundaria, método participativo de consenso, y preparación y escritura del documento final). Cada una de ellas usó técnicas y procedimientos estandarizados para el desarrollo de manuales basados en la evidencia.

Resultados: Se realizaron recomendaciones basadas en la evidencia sobre valoración pre-anestésica, manejo preoperatorio de condiciones médicas, educación y comunicación con los pacientes, consentimiento informado, traslado del paciente al área quirúrgica, marcación del sitio quirúrgico, estrategias para la prevención de infecciones, y lista de chequeo preoperatorio.

Conclusiones: Se espera que con el uso de este manual se minimice la incidencia de eventos que produzcan morbimortalidad en pacientes sometidos a procedimientos quirúrgicos.

Palabras clave: Quirófanos, Medicina Basada en la Evidencia, Anestesia, Infección de Herida Operatoria, Lista de Verificación.

Introduction

Protocols are crucial in clinical practice, in particular for ensuring safety in patient care, because their adoption minimizes variation in routine procedures, records, treatments and tasks. Protocols favour standardization and increase reliability of patient care, reducing human error while performing complex processes.1 The possibility of following protocols results in the ability to collect increasingly robust data, measure outcomes and indicators, and feed back into the processes. The recognition of critical processes in surgical patient care has led to the implementation of codes and effective communication techniques, and to a reduction of distractions and variations during their performance. This supports compliance, change and improvement actions to reduce life-threatening risks and to enhance patient wellbeing in the surgical setting. At present, patient safety is a field of study and research in all countries and has given rise to new knowledge and practices of undeniable benefit such as the well-known WHO Surgical Safety Checklist.2 Events regarding which there is more evidence available are the "never events":

- performing a surgical procedure in the wrong patient

- performing the wrong procedure in a patient

- performing a procedure in the wrong surgical site

- leaving behind a foreign body after surgery3

There are others such as surgical site infection and hypothermia.

In Colombia, the Ministry of Health and Social Protection has established the procedure and conditions for healthcare service licensures and has defined priority processes that are prerequisites for the licensure of surgical services. Two of these processes are patient preparation for surgery and patient transfer to the operating theatre. This protocol delineates the mandatory steps that need to be consistently and systematically applied by a multidisciplinary team that is informed and committed to the care and wellbeing of the surgical patient.

Although the protocol must be applied before the surgical procedure (pre-operative period), its implementation requires anticipating diagnostic or therapeutic measures that might be required during surgery (intra-operative period) or after surgery (post-operative period). It is for this reason that the protocol refers in some instances to the perioperative period (pre-, intra- and post-operative).

The ultimate reason for applying this manual is to minimize the incidence of events leading to morbidity and mortality in patients undergoing anaesthetic procedures.

Justification

The justification for this manual is compliance with the requirements of Resolution 2003 of the Ministry of Health, which defines the procedures and conditions for registration of Healthcare Institutions and for licensure of healthcare services. The Resolution mandates that a priority standardized procedure for all institutions providing surgical services at all levels of complexity, among others, is a protocol, manual or procedure for patient preparation for surgery and for the transfer of patients to the operating room.

The objective of this initiative was to develop an evidence-based clinical management manual for preparing patients for surgery, including the management of post-operative complications and post-operative follow-up.

Methodology

The process consisted of four phases. Standardized procedures and techniques were used in all phases for developing evidence-based guidelines and protocols:

- Creation of the development team

- Systematic review of the secondary literature

- Participatory method

- Preparation and drafting of the final document

Creation of the development team

A group of experts in anaesthesiology and epidemiology was put together and entrusted with the job of establishing the methodological and technical guidelines within the framework of the development of the protocol. The group included two methodological coordinators with experience developing evidence-based clinical practice guidelines and management, whose job was to coordinate the methodology of the process. Three additional groups were also created, one consisting of an anaesthesia specialist and an epidemiologist with experience in critical analysis of scientific evidence. All of the members of the development team agreed to participate in the process and signed the disclosure document in accordance with the regulations governing the development of evidence-based guidelines and protocols.

Systematic review of the secondary literature

A systematic review of the literature was conducted in order to identify the clinical protocols and the clinical practice guidelines dealing with the topic of the protocol. The unit of analysis for the review consisted of the articles published in scientific journals or in technical documents found in the grey literature:

- Evidence-based management protocols (or, eventually, clinical practice guidelines) that included indications or recommendations related to the clinical management by the anaesthesiology group, pertaining to the topic of the protocol

- Published to date since 2011

- Published in English or Spanish

Search strategy

Literature searches were designed by the search coordinator of the Cochrane Sexually Transmitted Infections group. A sensitive digital search strategy (Annex 1) was designed in order to find the papers that met the criteria described above. The search continued until August 24th, 2014.

The sources of information were the databases of the biomedical scientific literature Medline, Embase and Lilacs, plus grey literature sources (Google Scholar).

Selection ofthe evidence

A database of the papers that would potentially meet the criteria mentioned above was created on the basis of the results of the search strategies. This database was given to reviewers who worked independently to read the titles and abstracts in order to identify the papers that met the requirements. In the event of disagreement, the two reviewers would settle it through the exchange of communications. The full texts of the selected documents were downloaded for final screening.

Quality evaluation

The AGREE II tool was used to evaluate the quality of the evidence found in the previous step (Annex 2). Quality was evaluated on the basis of a paired analysis.4

Finally, a protocol that met the eligibility requirements was identified and was used as the source document for the adaptation of the clinical management protocol to the context described above. The basis for identifying the source document included the clinical judgement of the experts, relevance, completeness of the indications (recommendations) and quality of the document.

Rating ofevidence quality and recommendation strength

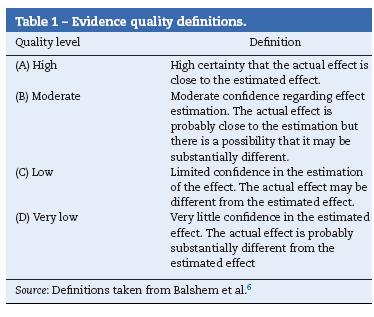

Grade was used to inform the quality of the source evidence and the strength of the recommendation5,6 (Tables 1 and 2).

Participatory method

A modified Delphi method was used. The development team chose the experts who would be asked to participate in the Delphi exercise. The meeting took place on September 18th at the S.C.A.R.E. premises, with the participation of 28 experts in anaesthesiology and epidemiology, and the following agenda:

- Presentation of the project

- Methodology of the meeting

- Results of the evidence

- Clinical content of the manual

- Vote

After presenting the clinical content of the manual, and following the discussion among the experts, agreement among them in relation to whether the protocol met the characteristics listed below was evaluated:

- Ease of implementation: Evaluates the possibility of the manual being readily used in the different institutions.

- Currency: Evaluates whether the indications are updated in relation to current evidence.

- Relevance: Evaluates whether the indications are relevant for the context of the majority of the surgical areas.

- Ethical considerations: Evaluates whether it is ethical to use this manual.

- Patient safety: Evaluates whether there is a high risk associated with the use of this protocol with patients.

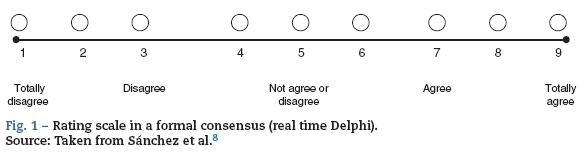

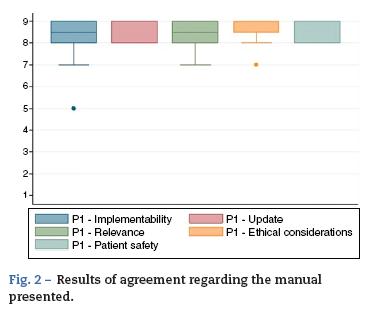

A nine-category ordinal scale was used for rating agreement in relation to each of the characteristics listed above (Fig. 1). Based on this, each of the proposed indications was rated as recommended (appropriate), contraindicated (inappropriate) or within a level of uncertainty. The rating was based on the Rand method (2004) cited by Sánchez Pedraza et al.8 Fig. 2 shows the results of the agreement among the participants in the consensus meeting.

Preparation and drafting of the final document

Finally, a model protocol was structured to include the justification for preparing the document, the methodology used and the adaptation of the proposed document, on the basis of the recommendations of the experts during the participatory exercise. The final document was prepared by the development team.

Fig. 2 shows the results of the agreement among the participants in the consensus meeting.

Conflicts of interest

All the members of the development team and the participants in the expert consensus meeting completed and signed the disclosure form in accordance with the format and recommendation from the Cochrane group.

Copyright

Permission was obtained for the use and translation of the guidelines contained in this series of manuals. Translation and partial reproduction were authorized by Lippincott Williams and Wilkins/Wolters Kluwer Health, Association of Anaesthetists of Great Britain & Ireland & the AAGBI Foundation, Institute of Clinical Systems Improvement.

Clinical content

Preparing a patient for a surgical procedure requires of a series of sub-processes usually performed sequentially. This is how they should proceed because one process is a prerequisite for the next. However, the whole sequence must be adjusted to the context of each patient, including the time interval between each of the stages, depending in particular on the type of intervention. The National Confidential Enquiry into Patient Outcome and Death classification (NCEPOD)9 was adopted for this protocol (Table 3).

Pre-anaesthesia assessment

The medical history and the physical examination are the best strategies to identify pre-operative problems. The time devoted to the pre-anaesthesia assessment may be optimized through the use of questionnaires (Table 4). These are not meant to replace the assessment by the anaesthetist but rather to facilitate identification of important points, and to document patient responses.10

Ideally, the pre-anaesthesia assessment must be done at least one week before an elective surgical procedure in order to allow time to provide adequate patient education. It is worth noting that this time interval may be adjusted to suit the specific characteristics of the individual patient and the type of surgical procedure.7

Patients, family members or caregivers must be advised that the pre-anaesthesia assessment is no substitute for health promotion, disease prevention, or early detection programmes.

- All patients undergoing diagnostic or therapeutic procedures must have a pre-anaesthesia assessment, except patients with no severe systemic diseases who require topical or local anaesthesia [GRADE C1].

Medical history and physical examination

The pre-anaesthesia assessment must include at least the following:

- Elective procedure

- Medical history

- Physical examination

- Reason for the surgical procedure

- Estimated surgical risk (Table 5)11

- Surgical history and complications

- Anaesthesia history and complications

- Allergies and intolerance to medications and other substances (specifying the type of reaction)

- Medication use (prescription, over-the-counter, herbal, nutritional, etc.)

- Disease history

- Nutritional status

- Cardiovascular status (Table 6)12,13

- Pulmonary status

- Functional class14-16

- Haemostatic status (personal and family history of abnormal bleeding)

- Possibility of symptomatic anaemia

- Possibility of pregnancy (women in childbearing age)

- Personal and family history of anaesthetic complications

- Cigarette smoking, use of alcohol and other substances

- Identification of risk factors for surgical site infection (cigarette smoking,

- Diabetes, obesity, malnutrition, chronic skin diseases)

- Weight, height and body mass index

- Vital signs: blood pressure, pulse (rate and regularity), respiratory rate

- Heart

- Lung

- Difficult airway probability

Risk models should not dictate management decisions, but they must be considered as one of the many pieces in the puzzle, and must be assessed together with the traditional information available to the practitioner.17

Pre-operative diagnostic tests. The paradigm regarding orders for diagnostic tests has changed in the whole world over the last few decades.18 Diagnostic tests not supported by the findings of the medical history or the physical examination are not cost-effective, do not grant medico-legal protection and might be deleterious for the patient.19-21Discussing the indications for ordering the long list of diagnostic tests available to clinical practice is beyond the scope of this protocol.

For patients undergoing non-cardiac surgery, the recommendation is to order diagnostic tests for cardiovascular assessment in accordance with any of the current international guidelines.17,22

Electrocardiogram

- Ordering a pre-operative electrocardiogram may be considered in patients 65 or over during the previous year before the surgical procedure [GRADE C2].

- A pre-operative electrocardiogram is not recommended in patients undergoing other low risk procedures, unless the medical history or the physical examination reveals that the patient is high risk [GRADE A1].

- An electrocardiogram is not indicated - regardless of age -in patients who will be taken to cataract surgery [GRADE A1].

Whole blood count

- A pre-operative whole blood count must be ordered on the basis of findings of the medical history and the physical examination, and the potential blood loss of the elective procedure [GRADE C1].

Electrolytes

- They are recommended in patients on chronic use of digoxin, diuretics, angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors or angiotensin receptor antagonists (ARAs) [GRADE D2].

Chest X-ray

- A chest X-ray must be obtained (AP and lateral views) in patients with signs or symptoms suggesting undiagnosed or chronic unstable cardiopulmonary disease [GRADE D2].

Pregnancy test

- It must be obtained in women in childbearing age who may be pregnant given a menstrual delay or given the explicit suspicion of pregnancy by the patient, or because of an uncertain pregnancy possibility (e.g. irregular menstruation) [GRADE C1].

Medical conditions

Cardiovascular diseases

- The presence of risk factors for perioperative cardiovascular complications must be assessed in all patients17 [GRADE A1].

- Therapy with beta-blockers must be continued during the perioperative period in patients with a historyofpermanent use of this type of medications [GRADE A1].

- The use of beta-blockers must be considered in patients with a high risk of cardiac complications (Table 5) undergoing vascular surgery [GRADE C2].

- The use of beta-blockers must be considered in patients with coronary heart disease or high cardiac risk (two or more risk factors) undergoing a surgical procedure of intermediate cardiovascular risk (Tables 5 and 6) [GRADE C2].

- Therapy with beta blockers must be started one to two weeks before surgery and the dose must be titrated in order to achieve a heart rate between 60 and 80 beats per minute [GRADE A1].

- Patients with permanent use of statins must continue to use them during the perioperative period [GRADE 1].

- The use of perioperative statin therapy must be considered in patients undergoing vascular or intermediate risk surgery [GRADE C2].

Haematological diseases or anticoagulation

- In cases where the medical history suggests potential coagulation problems, coagulation tests must be obtained [GRADE C1].

Coronary heart disease and coronary stents

- Surgery must be avoided for at least six weeks after the placement of a metal stent [GRADE C1].

- Surgery must be delayed for at least one year after the placement of a drug-eluting stent [GRADE C1].

- In the event it is not possible to postpone the surgery during the recommended time periods, dual anti-platelet aggregation therapy must be continued during the peri-operative period unless it is contraindicated (surgery with a high risk of bleeding, intracranial surgery, etc.) [GRADE C1].

- In the event the interruption of clopidogrel/ prasugrel/ticlopidine is considered necessary before the procedure, aspirin must be continued during the peri-operative period - if possible - in order to reduce cardiac risk [GRADE C1].

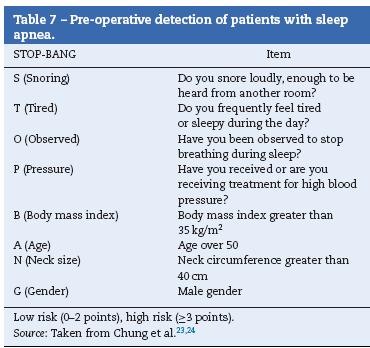

Sleep apnea

- The potential for sleep apnea in patients (Table 7) must be assessed and the results must be communicated to the surgical team [GRADE C1].

- Patients diagnosed with sleep apnea who receive positive airway pressure treatment (CPAP) must bring their device for use during the immediate post-operative period [GRADE B2].

Diabetes mellitus

- Blood sugar control must be targeted to achieve glycaemic concentration levels of 140-180 mg/dL and not to achieve more stringent targets (e.g. 80-110 mg/dL) [GRADE A1].

- Individualized assessment is required in order to issue instructions designed to avoid extreme glycaemic changes [GRADE C1].

- Long-acting insulin dose (glargine, NPH, etc.) must be reduced by 50% during the pre-operative period [GRADE C1].

- Oral anti-diabetic medications and short-acting insulins should not be used before the surgical procedure [GRADE C1].

- Sliding scale insulin regimens during the perioperative period must be used for treating hyperglycaemia in patients with difficult-to-manage diabetes mellitus [GRADE C1].

- GLP-1 agonists (exenatide, liraglutide, pramlintide) must be interrupted during the perioperative period [GRADE C1].

- DPP-4 inhibitors (sitagliptin) may continue to be used during the perioperative period [GRADE C2].

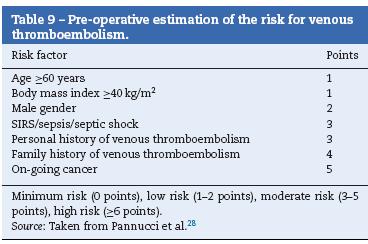

Chronic use medications (Table 9)

- A thorough determination of medication use by the patient is required (prescription drugs, over-the-counter medications, herbal products and nutritional supplements) at least one week before an elective surgical procedure [GRADE C1].

- In general, medications that contribute to homeostasis must be continued during the perioperative period, except for those that may increase the probability of adverse events (NSAIDs, ACE inhibitors/ARAs, insulin and blood sugar lowering drugs, anticoagulants, biological, medications for osteoporosis, hormonal therapy, etc.) [GRADE C1].

In general, all medications that do not contribute to maintaining homeostasis must be interrupted (non-prescription drugs, herbal or natural products, nutritional supplements, etc.) [GRADE C1].

Smoking cessation

- Patients must be encouraged to stop smoking [GRADE C1].

Prophylaxis for thromboembolism (Table 8)

- All patients must be assessed for the perioperative risk of venous thromboembolism, and the quantification must be documented in the clinical record. It is recommended to discuss the appropriate measures for preventing thromboembolic complications with other members of the surgical team.28

Patient education and communication

Recommendations on pre-operative fasting

Recommendations on pre-operative fasting (NPO) have been revised and simplified considerably over the past decade. Management guidelines have been published establishing the "2, 4, 6, 8 hour rule", which is applied to patients of all ages.29,30 Patients must be educated and informed of the fasting requirements with sufficient time in advance.

- The recommended fasting period for clear liquids such as water, fruit juices with no pulp, carbonated drinks, clear tea and coffee is 2 h or more before the surgical procedure [GRADE B1].

- The recommended fasting period for breast milk is 4 h or more before the surgical procedure [GRADE B1].

- The recommended fasting period for milk formula, non-human milk and light meals (such as toast) is 6 h or more before the surgical procedure [GRADE B1].

- The fasting period for fried or fat food, or meat, must be 8 h or more, because these foods may prolong gastric emptying [GRADE B1].

Pre-operative bathing and shaving

In order to prevent infections, patients must be encouraged to bathe on the day of the surgical procedure. They must be told not to shave or remove any hair at, or close to, the surgical site. Every institution must establish specific guidelines for its patient population and the specific surgical procedures they perform (see Skin Preparation).

Communication with patients and caregivers

A reliable mechanism must be established for communicating the result of the pre-anaesthesia assessment, including the results of diagnostic tests and instructions for surgical site marking, aside from patient identification before the procedure (Table 10).7

- In cases of elective procedures, it is recommended to provide patients or caregivers with printed material with the most relevant instructions for preparing for the surgical procedure [GRADE D2].

Informed consent

Despite the unique challenges of obtaining the informed consent for anaesthetic procedures, patients, parents or caregivers must be informed of the general and specific anaesthetic risks, and about anaesthetic care. Strategies to improve understanding of the information must be implemented in order to ensure that decision-makers are adequately informed.31,32

- The anaesthesia informed consent must be given to all patients (signed by the patient, parents or caregivers) who are taken to diagnostic or therapeutic procedures [GRADE< A1].

Patient transfer to the operating theatre (operating rooms)

Patients must be transferred to the operating room in a manner consistent with their clinical condition. Transfer implies that patients require care in different areas of the health facilities and, consequently, there is a need for patient handover and reception processes. There is a generalized consensus at present in the sense that robust and structured handover processes are critical for safe patient care. The use of checklists and software tools to facilitate the transfer process may improve reliability and help eliminate stress for the healthcare staff. Transfer and handover processes must be adapted to every specific clinical setting.33

In view of the above, there are two groups of patients that require specific considerations:

- Outpatients and non-critically ill inpatients.

- Critically ill patients. Aside from the above,

- Patient transfers to the operating theatre must be adapted to the individual clinical conditions of the patient (critically ill or non-critically ill). The handover and reception process must be documented in the clinical record [GRADE C1].

- In order to prevent injuries from falls, patients cannot ambulate during transfer. They must be transferred in a wheel chair or trolley.

- Devices to ensure safe transfer must be available in accordance with the specific needs of the individual patient (e.g. oxygen, infusion pumps, etc.).

- At least one paramedic must participate in transfers.

- Transfer with monitoring, at least non-invasive blood pressure, continuous electrocardiogram and pulse oxymetry

- Invasive ventilation support devices must be available in accordance with the clinical indications, with the possibility of giving positive end-expiratory pressure (PEEP)

- The leader of the transfer group must be a physician, supported by paramedical staff.

Surgical site marking

A wrong surgery may be the result of misinformation of the surgical team or misperception of patient orientation. The key to prevent such an event is to have multiple independent information checkpoints. Inconsistencies between the pre-anaesthesia assessment, the informed consent and the surgeon's notes in relation to the medical history and the physical examination must be addressed, ideally, before the start of any pre-operative procedure.34Before marking the surgical site, patient identification and the correct site for the surgical procedure must be checked as follows:

- Information contained in the informed consent

- Information contained in the clinical record

- Diagnostic tests

- Interview with the patient, parent or caregiver [GRADE A1]

Infection prevention

Post-operative infection is a serious complication. It is the most frequent source of in-hospital morbidity for patients undergoing surgical procedures, and it is associated with increased length of hospital stay, a higher risk of mortality and lower quality of life.35,36

It may happen as a result of the surgical procedure and also as a result of anaesthetic procedures. Several strategies have been described to diminish the risk of post-operative infection from the point of view of the anaesthetist: They include, among others

- Prophylactic antibiotics

- Perioperative normothermia

- Adequate skin preparation37-39

Antibiotic management

The pre-operative use of prophylactic antibiotics has been shown to reduce the risk of post-operative surgical site infection. Recommendations have been published on the type of antibiotics (Table 11) and their dosing (Table 12) for use as pre-operative prophylaxis in accordance with the type of surgical procedure.40 Pre-operative antibiotics must be given with the goal of achieving bactericidal tissue concentrations at the time of the incision. For most antibiotics, this concentration is achieved 30 min after administration. Vancomycin and flu-oroquinolones must be given within the 120 min leading to the procedure because they require longer infusion times.40 In those cases in which antibiotics cannot be given within the recommended time intervals (e.g. in a child without vascular access), they must be given as soon as the impediment is resolved. Late administration of antibiotic prophylaxis does not reduce its effectiveness.41

- All patients must be assessed for known medication allergies [GRADE C1].

- An adequate prophylactic antibiotic must be given, depending on the type of surgery, between 30 min and 2 h before the start of the procedure. This time interval will depend on the antibiotic used [GRADE C1].

- Prophylactic antibiotics, in non-cardiac surgery, must be interrupted within 24 h after the end of the procedure [GRADE C1].

- Prophylactic antibiotics, in cardiac surgery, must be interrupted within 48 h after the end of the procedure [GRADE C1].

Prevention ofendocarditis

- Patients with a diagnosis of cardiac valve disease undergoing surgical procedures must receive adequate antibiotic prophylaxis [GRADE C1].

Procedures in patients with a history of joint replacement

- Patients with joint prostheses must not receive prophylactic antibiotics for the prevention of prosthesis-associated infection [GRADE C1].

Bowel preparation in colorectal surgery

- The use of mechanical bowel preparation is not recommended for reducing the post-operative risk of surgical site infection [GRADE A1].

- At the time of surgery, all patients must receive a prophylactic dose of effective antibiotics against colon and skin flora [GRADE A1].

Normothermia plan and temperature management

Temperature must be monitored in all patients receiving anaesthesia and who are expected to undergo changes in central temperature49,50SMD. There are many means and sites for measuring central temperature with different levels of accuracy and ease of use (oral, tympanic, oesophageal, axillary, skin, bladder, rectal, tracheal, nasopharyngeal, pulmonary artery catheter). The selection of the site depends on the access and the type of surgery.51

- trategies must be put in place in order to reduce the risk of intra-operative hypothermia and associated complications (surgical site infection, cardiac complications, increased bleeding, etc.) [GRADE A1].

Skin preparation

Most surgical site infections are caused by normal skin flora. The surgical site must be assessed before skin preparation. The skin must be assessed for the presence of:

- nevi

- warts

- rash

- other skin conditions

Inadvertent lesion elimination may create the opportunity for wound colonization.52Recommendations for skin preparation must be applied for anaesthetic procedures as well as for insertion of central vascular accesses.53

Application ofantiseptic solutions

There are several antiseptic agents available for pre-operative skin preparation of the incision site (Table 13), but there is limited evidence to recommend the use of one antiseptic agent over another.54Selecting the ideal agent according to each group of patients requires careful consideration. Some antiseptic agents may injure mucosal tissue and others are highly flammable.

The prepared area must be sufficiently large in order to allow for the extension of the incision or the placement of drains. The staff must have knowledge of the different techniques for skin preparation, including the preservation of skin integrity and the prevention of injuries to the skin.52 The preparation process must follow certain special considerations:

- Areas with large microbial counts must be the last to be prepared

- Colostomies must be isolated with antiseptic-impregnated gauze and left for the end of the preparation process

- The use of normal saline solution is recommended for preparing burnt or traumatized skin areas

- The use of chlorhexidine and alcohol-based products must be avoided in mucosal tissue

- Allow enough contact time for the antiseptic agents before draping

- Allow enough time for complete evaporation of flammable agents

- Prevent antiseptics to pool under the patient or the equipment

Skin preparation must be documented in the patient's chart. Skin preparation policies and procedures must be reviewed periodically in order to evaluate new evidence.

- Areas of the skin that will undergo therapeutic (surgery), anaesthetic (regional anaesthesia) and diagnostic (catheter insertion) procedures must be prepared with antiseptic solution in order to reduce the risk of infection [GRADE A1].

Hair removal

The use of shavers may result in cuts and skin abrasions and should not be allowed. The use of clipping devices is recommended for removing hair close to the skin, leaving behind hair that is 1 mm long. Clippers usually have disposable heads, or reusable heads that may be disinfected between patients. They do not touch the skin, thus reducing cuts and abrasions. Hair removal creams dissolve hair through the chemical action of the product. However, the process is lengthier, lasting between 5 and 20 min. Chemical hair removal may irritate the skin or give rise to allergic reactions. There are some special considerations for hair removal:

- Hair removal must be avoided, unless hair may interfere with the procedure55

- Hair removal must be the exception, not the rule

- When required, hair removal must be done as close to the time of the surgical procedure as possible. There is no evidence of a specific time period for avoiding hair removal on or close to the surgical site. Shaving more than 24 h before the procedure increases the risk of infection56

- Hair removal in the sterile field may contaminate the surgical site and the drapes because of loose hair

- For some surgical procedures, hair removal may not be necessary. Patients requiring immediate surgical intervention may not have time for hair removal

- The staff in charge of removing hair must have the training in the use of the appropriate technique

- Policies and procedures must state when and how to remove hair at the incision site. Hair removal must be performed under the doctor's orders or in accordance with the protocol for certain surgical procedures

- If hair is removed, it must be documented in the clinical record. The documentation must include skin condition at the surgical site, the name of the person who did the hair removal, the method used, the area of the body and the time when it was done.

Pre-operative checklist

Checklists have become commonplace in healthcare practice as a strategy to improve patient safety. The World Health Organization (WHO) has implemented a proposed checklist in more than 120 countries (Fig. 3). Emphasis is made on the use of these lists for the most critical processes impacting patient safety:

- Safe anaesthesia and risk of a difficult airway

- Right surgical site

- Infection prevention

- Teamwork

The intent of the checklist as a safety tool is to standardize and increase performance predictability of the surgical team in a whole range of situations and clinical settings, and with different people.57Hence, checklists have been equated with best practices in high-risk areas such as anaesthesia, and have been adopted in Colombia as a minimum safety standard in anaesthesiology.32,58

- In all patients undergoing surgical procedures, compliance with the pre-operative procedures, staff and equipment availability must be ascertained using the WHO checklist [GRADE A1].

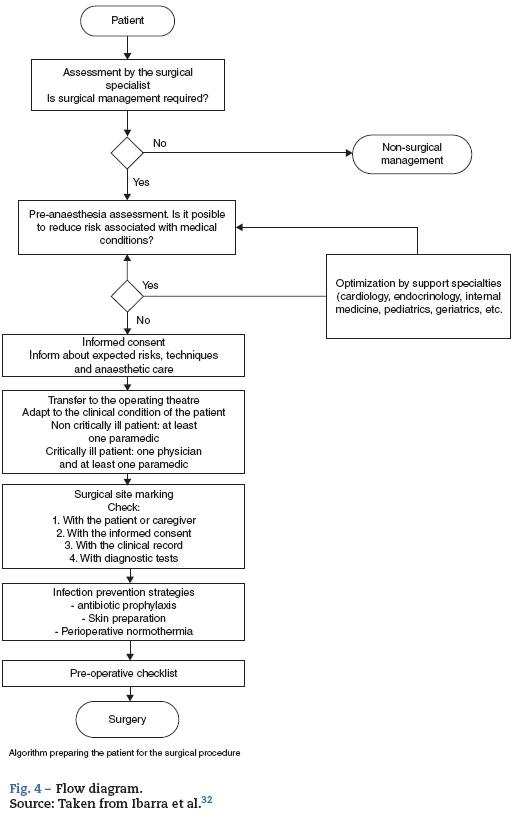

Flow diagram

The flow diagram of patient preparation for surgery shows several sequential sub-processes, each being a prerequisite for the next (Fig. 4).

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Annex 1. Systematic search of clinical protocols for the management of pre-, intra-and post-operative anaesthesia.

Annex 2. AGREE II Calculator

Se puede consultar material adicional a este artículo en su versión electrónica disponible en http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.rcae.2014.11.004.

References

1. Smith A, Alderson P. Guidelines in anaesthesia: support or constraint? Br J Anaesth. 2012;109:1-4. [ Links ]

2. Mahajan RP. The WHO surgical checklist. Best Pract Res Clin Anaesthesiol. 2011;25:161-8. [ Links ]

3. Michaels RK, Makary MA, Dahab Y, Frassica FJ, Heitmiller E, Rowen LC, et al. Achieving the National Quality Forum's "Never Events": prevention of wrong site, wrong procedure, and wrong patient operations. Ann Surg. 2007;245:526-32. [ Links ]

4. Brouwers MC, Kho ME, Browman GP, Burgers JS, Cluzeau F, Feder G, et al. AGREE II: advancing guideline development, reporting and evaluation in health care. CMAJ. 2010;182:E839-42. [ Links ]

5. Andrews JC, Schünemann HJ, Oxman AD, Pottie K, Meerpohl JJ, Coello PA, et al. GRADE guidelines: 15 going from evidence to recommendation-determinants of a recommendation's direction and strength. J Clin Epidemiol. 2013;66:726-35. [ Links ]

6. Balshem H, Helfand M, Schünemann HJ, Oxman AD, Kunz R, Brozek J, et al. GRADE guidelines: 3 rating the quality of evidence. J Clin Epidemiol. 2011;64:401-6. [ Links ]

7. Card R, Sawyer M, Degnan B, Harder K, Kemper J, Marshall M, et al. Perioperative protocol. Inst Clin Syst Improv. 2014. [ Links ]

8. Sánchez Pedraza R, Jaramillo González LE. Metodología de calificación y resumen de las opiniones dentro de consensos formales. Rev Colomb Psiquiatr. 2009;38:777-85. [ Links ]

9. National confidential enquiry into patient outcome and death [Internet]. [cited 27.09.14]. Available from: http://www.ncepod.org.uk/. [ Links ]

10. Muckler VC, Vacchiano CA, Sanders EG, Wilson JP, Champagne MT. Focused anesthesia interview resource to improve efficiency and quality. J Perianesth Nurs. 2012;27:376-84. [ Links ]

11. Glance LG, Lustik SJ, Hannan EL Osler TM, Mukamel DB, Qian F, et al. The Surgical Mortality Probability Model: derivation and validation of a simple risk prediction rule for noncardiac surgery. Ann Surg. 2012;255:696-702. [ Links ]

12. Lee TH, Marcantonio ER, Mangione CM, Thomas EJ, Polanczyk CA, Cook EF, et al. Derivation and prospective validation of a simple index for prediction of cardiac risk of major noncardiac surgery. Circulation. 1999;100:1043-9. [ Links ]

13. Gupta PK, Gupta H, Sundaram A, Kaushik M, Fang X, Miller WJ, et al. Development and validation of a risk calculator for prediction of cardiac risk after surgery. Circulation. 2011;124:381-7. [ Links ]

14. Myers J, Do D, Herbert W, Ribisl P, Froelicher VF. A nomogram to predict exercise capacity from a specific activity questionnaire and clinical data. Am J Cardiol. 1994;73:591-6. [ Links ]

15. Myers J, Bader D, Madhavan R, Froelicher V. Validation of a specific activity questionnaire to estimate exercise tolerance in patients referred for exercise testing. Am Heart J. 2001;142:1041-6. [ Links ]

16. Hlatky MA, Boineau RE, Higginbotham MB, Lee KL, Mark DB, Califf RM, et al. A brief self-administered questionnaire to determine functional capacity (the Duke Activity Status Index). Am J Cardiol. 1989;64:651-4. [ Links ]

17. Kristensen SD, Knuuti J, Saraste A, Anker S, B0tker HE, De Hert S, et al. ESC/ESA Guidelines on non-cardiac surgery: cardiovascular assessment and management: The Joint Task Force on non-cardiac surgery: cardiovascular assessment and management of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) and the European Society of Anaesth. Eur J Anaesthesiol. 2014;35:2383-431. [ Links ]

18. Smetana GW, Macpherson DS. The case against routine preoperative laboratory testing. Med Clin North Am. 2003;87:7-40. [ Links ]

19. Michota FA, Frost SD. The preoperativ evaluation: use the history and physical rather than routine testing. Cleve Clin J Med. 2004;71:63-70. [ Links ]

20. Hepner DL. The role of testing in the preoperative evaluation. Cleve Clin J Med. 2009;76 Suppl. 4:S22-7. [ Links ]

21. Johansson T, Fritsch G, Flamm M, Hansbauer B, Bachofner N, Mann E, et al. Effectiveness of non-cardiac preoperative testing in non-cardiac elective surgery: a systematic review. Br J Anaesth. 2013;110:926-39. [ Links ]

22. Fleisher LA, Fleischmann KE, Auerbach AD, Barnason SA, Beckman JA, Bozkurt B, et al. ACC/AHA guideline on perioperative cardiovascular evaluation and management of patients undergoing noncardiac surgery: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. Circulation. 2014, http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jacc.2014.07.944. Aug 1, pii: CIR.0000000000000105, [Epub ahead of print] [ Links ].

23. Chung F, Yegneswaran B, Liao P, Chung SA, Vairavanathan S, Islam S, et al. STOP questionnaire: a tool to screen patients for obstructive sleep apnea. Anesthesiology. 2008;108:812-21. [ Links ]

24. Proczko MA, Stepaniak PS, de Quelerij M, van der Lely FH, Smulders JF, Kaska L, et al. STOP-Bang and the effect on patient outcome and length of hospital stay when patients are not using continuous positive airway pressure. J Anesth. 2014, http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s00540-014-1848. May 29, [Epub ahead of print] [ Links ].

25. Fenger-Eriksen C, Münster A-M, Grove EL. New oral anticoagulants: clinical indications, monitoring and treatment of acute bleeding complications. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 2014;58:651-9. [ Links ]

26. González Naranjo LA, Ramírez Gómez LA. Manejo perioperatorio de la terapia antirreumática. Iatreia. 2011;24:308-19. [ Links ]

27. Polachek A, Caspi D, Elkayam O. The perioperative use of biologic agents in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Autoimmun Rev. 2012;12:164-8. [ Links ]

28. Pannucci CJ, Laird S, Dimick JB, Campbell DA, Henke PK. A validated risk model to predict 90-da VTE events in postsurgical patients. Chest. 2014;145:567-73. [ Links ]

29. Apfelbaum JL, Caplan RA, Connis RT, Epstein BS, Nickinovich DG, Warner MA. Practice guidelines for preoperative fasting and the use of pharmacologic agents to reduce the risk of pulmonary aspiration: application to healthy patients undergoing elective procedures: an updated report by the American Society of Anesthesiologists Committee on Standards and Practice Parameters. Anesthesiology. 2011;114:495-511. [ Links ]

30. Rincón-Valenzuela DA. Guía de práctica clínica basada en la evidencia para la prevención de aspiración pulmonar en pacientes que requieren manejo de la vía aérea. Rev Colomb Anestesiol. 2011;39:277-8. [ Links ]

31. Tait AR, Teig MK, Voepel-Lewis T. Informed consent for anesthesia: a review of practice and strategies for optimizing the consent process. Can J Anaesth. 2014;61:832-42. [ Links ]

32. Ibarra P, Robledo B, Galindo M, Nino C, Rincón DA. Normas mínimas 2009 For ejercicio de la anestesiología en Colombia. Rev Colomb Anestesiol. 2009;37:235-53. [ Links ]

33. Kalkman CJ. Handover in the perioperative care process. Curr Opin Anaesthesiol. 2010;23:749-53. [ Links ]

34. Clarke JR, Johnston J, Blanco M, Martindell DP. Wrong-site surgery: can we prevent it? Adv Surg. 2008;42:13-31. [ Links ]

35. Anthony T, Murray BW, Sum-Ping JT, Lenkovsky F, Vornik VD, Parker BJ, et al. Evaluating an evidence-based bundle for preventing surgical site infection: a randomized trial. Arch Surg. 2011;146:263-9. [ Links ]

36. Murray BW, Huerta S, Dineen S, Anthony T. Surgical site infection in colorectal surgery: a review of the nonpharmacologic tools of prevention. J Am Coll Surg. 2010;211:812-22. [ Links ]

37. Gifford C, Christelis N, Cheng A. Preventing postoperative infection: the anaesthetist's role. Contin Educ Anaesthesia, Crit Care Pain. 2011;11:151-6. [ Links ]

38. Mauermann WJ, Nemergut EC. The anesthesiologist's role in the prevention of surgical site infections. Anesthesiology. 2006;105:413-21. [ Links ]

39. Forbes SS, McLean RF. Review article: the anesthesiologist's role in the prevention of surgical site infections. Can J Anaesth. 2013;60:176-83. [ Links ]

40. Bratzler DW, Dellinger EP, Olsen KM, Perl TM, Auwaerter PG, Bolon MK, et al. Clinical practice guidelines for antimicrobial prophylaxis in surgery. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2013;70:195-283. [ Links ]

41. Hawn MT, Richman JS, Vick CC, Deierhoi RJ, Graham LA, Henderson WG, et al. Timing of surgical antibiotic prophylaxis and the risk of surgical site infection. JAMA Surg. 2013;148:649-57. [ Links ]

42. Zanetti G, Giardina R, Platt R. Intraoperative redosing of cefazolin and risk for surgical site infection in cardiac surgery. Emerg Infect Dis. 2001;7:828-31. [ Links ]

43. Bratzler DW, Houck PM, Richards C, Steele L, Dellinger EP, Fry DE, et al. Use of antimicrobial prophylaxis for major surgery: baseline results from the National Surgical Infection Prevention Project. Arch Surg. 2005;140:174-82. [ Links ]

44. Fonseca SNS, Kunzle SRM, Junqueira MJ, Nascimento RT, de Andrade JI, Levin AS. Implementing 1-dose antibiotic prophylaxis for prevention of surgical site infection. Arch Surg. 2006;141:1109-13. [ Links ]

45. Zmora O, Pikarsky AJ, Wexner SD. Bowel preparation for colorectal surgery. Dis Colon Rectum. 2001;44:1537-49. [ Links ]

46. Jimenez JC, Wilson SE. Prophylaxis of infection for elective colorectal surgery. Surg Infect (Larchmt). 2003;4: 273-80. [ Links ]

47. Nichols RL, Choe EU, Weldon CB. Mechanical and antibacterial bowel preparation in colon and rectal surgery. Chemotherapy. 2005;51 Suppl. 1:115-21. [ Links ]

48. Mekako AI, Chetter IC, Coughlin PA, Hatfield J, McCollum PT. Randomized clinical trial of co-amoxiclav versus no antibiotic prophylaxis in varicose vein surgery. Br J Surg. 2010;97: 29-36. [ Links ]

49. Horosz B, Malec-Milewska M. Methods to prevent intraoperative hypothermia. Anaesthesiol Intensive Ther. 2014;46:96-100. [ Links ]

50. Sajid MS, Shakir AJ, Khatri K, Baig MK. The role of perioperative warming in surgery: a systematic review. Sao Paulo Med J. 2009;127:231-7. [ Links ]

51. Sessler DI. Temperature monitoring and perioperative thermoregulation. Anesthesiology. 2008;109:318-38. [ Links ]

52. AORN. Recommended practices for skin preparation of patients. AORN J. 2002;75:184-7. [ Links ]

53. Moureau N, Lamperti M, Kelly LJ, Dawson R, Elbarbary M, van Boxtel a JH, et al. Evidence-based consensus on the insertion of central venous access devices: definition of minimal requirements for training. Br J Anaesth. 2013;110:347-56. [ Links ]

54. Dumville JC, McFarlane E, Edwards P, Lipp A, Holmes A. Preoperative skin antiseptics for preventing surgical wound infections after clean surgery. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013;3:CD003949. [ Links ]

55. Sebastian S. Does preoperative scalp shaving result in fewer postoperative wound infections when compared with no scalp shaving? A systematic review. J Neurosci Nurs. 2012;44:149-56. [ Links ]

56. Mangram AJ, Horan TC, Pearson ML, Silver LC Jarvis WR. Guideline for prevention of surgical site infection, 1999 Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Hospital Infection Control Practices Advisory Committee. Am J Infect Control. 1999;27:97-132. [ Links ]

57. Weiser TG, Berry WR. Review article: perioperative checklist methodologies. Can J Anaesth. 2013;60:136-42. [ Links ]

58. Schleppers A, Prien T, Van Aken H. Helsinki Declaration on patient safety in anaesthesiology: putting words into practice - experience in Germany. Best Pract Res Clin Anaesthesiol. 2011;25:291-304. [ Links ]

text in

text in