Services on Demand

Journal

Article

Indicators

-

Cited by SciELO

Cited by SciELO -

Access statistics

Access statistics

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in

SciELO

Similars in

SciELO -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Colombian Journal of Anestesiology

Print version ISSN 0120-3347

Rev. colomb. anestesiol. vol.43 no.1 Bogotá Jan./Mar. 2015

Case report

Anaesthetic implications in Von Recklinghausen disease: A case report

Implicaciones anestésicas en la enfermedad de Von Recklinghausen

Rosana Guerrero-Domíngueza,*, Daniel López-Herrera-Rodrígueza, Jesús Acosta-Martíneza, Ignacio Jiméneza

a MD, Anaesthetist, Hospitales Universitarios Virgen del Rocío, Sevilla, Spain

* Corresponding author at: Avda. Ramón Carande n.° 11, 4.° E, 41013 Sevilla, Spain. E-mail address rosanabixi7@hotmail.com (R. Guerrero-Domínguez).

Article info

Article history: Received 26 June 2014 Accepted 22 August 2014 Available online 12 December 2014

Abstract

Von Recklinghausen disease or neurofibromatosis Type I (NF1) is an autosomal dominant disease with a wide spectrum of clinical manifestations. Neurofibromas are the characteristic lesions. This disorder is associated with important anaesthetic considerations, mainly when neurofibromas occur in the oropharynx and larynx, leading to difficult laryngoscopy and tracheal intubation. We describe the anaesthetic management of a patient with NF1 under general anaesthesia for facial neurofibroma excision. We performed a brief review of the literature with the aim of optimizing the anaesthetic management and reducing the number of complications associated with the systemic manifestations of this syndrome.

Keywords: Neurofibroma, Neurofibromatoses, Anesthesia, Airway management, Cafe-au-Lait Spots.

Resumen

La enfermedad de Von Recklinghausen (EVR) o neurofibromatosis tipo I (NF1) es una enfermedad con herencia autosómica dominante con un amplio espectro de manifestaciones clínicas. Los neurofibromas son las lesiones características. Este trastorno se asocia con importantes consideraciones anestésicas, principalmente cuando los neurofibromas aparecen en la orofaringe y laringe, produciendo dificultades en la laringoscopia y en la intubación endotraqueal. Describimos el manejo anestésico de un paciente con NF1 bajo anestesia general para extirpación de neurofibromas faciales. Hemos realizado un breve repaso de la literatura existente para optimizar el manejo anestésico y reducir el número de complicaciones asociadas con las manifestaciones sistémicas de este síndrome.

Palabras clave: Neurofibroma, Neurofibromatosis, Anestesia, Manejo de la vía Aérea, Manchas Café Con Leche.

Introduction

Von Recklinghausen disease (VR) or neurofibromatosis type I (NF1) is an autosomal dominant disorder characterized by the propensity to form ectodermal and mesodermal tissue tumours,1 affecting primarily the nervous system and the skin.2 Friedrich Recklinghausen identified the origin of the tumours in the nervous tissue in 1882.1,3 The pathophysio-logy is characterized by a mutation of the NF1 gene located on chromosome 17q11.2, responsible for secreting neurofi-bromin, a protein that inhibits abnormal cell growth.1,2 The clinical spectrum of this disorder is quite broad, characterized mainly by skin neurofibromata and café-au-lait spots.2

Clinical case

We present a case of a 14-year-old patient with a personal history of VR and a surgical history of excision of a right hemi-cranial plexiform neurofibroma. No fibromas of the oral cavity or predictors of a difficult airway were found during airway exploration. The patient did not report dyspnoea, dysphagia or changes in voice tone that could suggest the presence of laryngeal fibromas. Additional tests included biochemistry, whole blood count, coagulation tests and a chest radiograph, all of which came back normal.

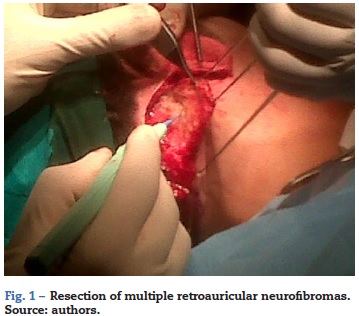

The patient presented important facial asymmetry as a result of multiple retroauricular neurofibromas that disfigured the face and made it impossible for him to use reading glasses. It was decided to excise the neurofibromas and attempt facial remodelling.

After setting up the usual non-invasive monitoring using blood pressure, electrocardiogram, pulse oximetry (SpO2) and neuromuscular blockade with TOF Watch® SX monitoring, a peripheral venous access was established on the back of the left hand. The anaesthetic induction was done using propofol 130 mg, fentanyl 120 µg, and rocuronium 30 mg. There was no airway obstruction after induction during manual ventilation with a facial mask. Endotracheal intubation proceeded uneventfully and mechanical ventilation was instituted. Laryngoscopy did not reveal gross laryngeal fibromas. Sevoflurane at 1 MAC and fentanyl according to analgesic needs were used during anaesthetic maintenance. The procedure lasted 160 min (Fig. 1) and proceeded uneventfully.

At the end of the procedure, the patient received metamizol 2 g, ondansentron 4 mg, atropine 0.6 mg and neostigmine 2 mg, and was extubated upon reaching a train-of-four value of 0.9. The patient was then taken to the post-anaesthetic care unit and had a favourable course.

Discussion

Neurofibromatosis (NF) is a congenital disease of the group of autosomal dominant neurocutaneous phakomatoses including also the tuberous sclerosis complex, the Hippel-Lindau syndrome and the basal-cell nevi syndrome.4 It is possible to distinguish two types of neurofibromatosis on the basis of the phenotypical and genetic characteristics: NF1 or VR and neurofibromatosis type 2 (NF2).

The incidence of VR is 1 in every 2500-3300 births5 and the prevalence is 1 in every 5000 inhabitants.5 Although it has a 100% penetrance,5 expression varies5,6 with 50% of the patients having no family history,5,7 which implies a spontaneous mutation.6

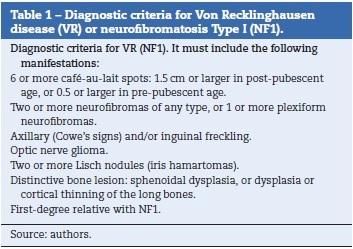

Despite significant advances in molecular genetics8,9 the diagnosis of VR is made when a series of clinical criteria are met (Table 1).5

Café-au-lait spots are found in 95% of adults with VR.5 Neurofibromas are the most characteristic lesion10 representative of this disorder and they can be divided into three types depending on their clinical and histopathological characteristics5: cutaneous (found in 95% of patients), nodular and plexiform neurofibromas. Plexiform neurofibromas are found in 30% of cases, causing severe body deformities.5 They may become malignant in 2-16% of cases9 and they are the primary cause of morbidity and mortality.5

Lisch nodules are present in 95% of cases. They may be associated with bone abnormalities, pheochromocytoma,11,12 gut tumours,13 carcinoid tumours, spinal or cerebral,14 vertebral deformities, juvenile chronic myelogenous leukaemia,5 and growth and mental retardation.1,15

Neurofibromatosis Type 2 is diagnosed on the basis of a series of clinical criteria, defined by the presence of bilateral vestibular schwannomas leading to hearing loss,5 cataracts, and central nervous system involvement, such as menin-gioma.

VR poses a challenge to anaesthetists, including a potentially difficult airway, abnormalities of the spinal anatomy and peripheral neurofibromas;16 hence the need for a careful systemic assessment before selecting the anaesthetic technique.17

Classically, general anaesthesia has been considered safer since the presence of intracranial neuromas or the existence of unknown spinal neuromas (up to 40%16 of cases) may worsen the neurological picture when locoregional anaesthetic techniques are used,17,18 with devastating consequences such as haematomas and paralysis.16 Gliomas, meningiomas, hydrocephalus, spinal tumours and spina bifida have been described in VR, discouraging the use of locoregional anaesthesia when these findings are present.19

Macroglossia, abnormal formations in the tongue, pharynx, larynx2 and even supraglottic plexiform fibromas5 may prevent endotracheal intubation2,19 and determine upper airway obstruction during anaesthetic induction. These lesions must be suspected after a detailed history and patient report of dysphagia, dysarthria, stridor and voice changes.5 Facial malformations may result in facial asymmetry due to intraosseous involvement6 and contribute to difficult ventilation when face mask and orotracheal intubation are used.

Consequently, as anaesthetists we are required to perform a thorough assessment to identify difficult airway predictors, as well as an adequate interview designed to detect intraoral lesions.2 If a difficult airway is expected, awake fibre optic bronchoscopy intubation must be considered as the technique of choice.2

Multisystem involvement in VR requires special attention to other potential intra-operative findings such as hypertension, which could be related with an unknown pheochromocytoma (up to 20%19 of patients with VR) or renal artery stenosis.

Other causes of pheochromocytoma that need to be ruled out include von Hippel-Lindau syndrome, multiple endocrine neoplasia Type 2B (MEN 2B) and paraganglioma syndromes.20 The finding of a pheochromocytoma mandates individualized pre-operative management in order to avoid life-threatening intra-operative hypertensive crises. Pre-operative blood pressure control is based on alpha receptor blockade using prazosin or phenoxybenzamine to replenish plasma volume and counteract the vasopressor effects of high catecholamine levels, followed by beta blockade.

Other considerations include respiratory compromise with intrapulmonary fibromas and pulmonary fibrosis, and cardiovascular compromise with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy or mediastinal tumours compressing the superior vena cava, beside hypertension.

The presence of scoliosis compromises cardiopulmonary function, leading to right ventricular failure.5 Other anaesthetic considerations include epilepsy, carcinoid tumours and obstructive ureteral stenosis due to neurofibromas.5

Exceptionally, some cases have been described of altered sensitivity to neuromuscular blockers,1 giving rise to prolonged episodes of apnea of unexplained mechanism.19,21

In summary, we reviewed the existing literature in order to avoid deleterious effects from our clinical anaesthesia practice because of the multi-organ involvement in a disease that may give rise to multiple perioperative adverse events.

Patient perspective

The patient perceived the anaesthetic management as the most beneficial given the surgical intervention and the associated anaesthetic risks.

Informed consent

The informed consent was obtained.

Information disclosure

Patient information has remained confidential.

Ethics committee

The study was approved by the ethics committee.

Funding

We received no funding for this work.

Conflict of interest

There is no conflict of interest.

References

1. Del Castillo AS, Brito M, Martínez J, Sardi N. Manejo anestésico en cesárea de urgencia en. pacientes con enfermedad de Von Recklinghausen: Presentación de dos casos. Rev Mex Anestesiol. 2009;32:134-7. [ Links ]

2. Lee WY, Shin YS, Lim CS, Chung WS, Kim BM. Spinal anesthesia for emergency cesarean section in a preeclampsia patient diagnosed with type 1 neurofibromatosis. Korean J Anesthesiol. 2013;65 6 Suppl.:S91-2. [ Links ]

3. Von Recklinghausen FD. Ueber die multiplen Fibrome der Haut und ihre Beziehung zu den multiple Neuromen. Berlin: Hirschwald; 1882. [ Links ]

4. Guido Lastra, Roberto Franco, Pedro Nel Rueda P, Lina P, Pradilla S, Óscar Paz C. Neoplasia endocrina múltiple. Rev Fac Med Unal [online]. 2004;52:3. [ Links ]

5. Hirsch NP, Murphy A, Radcliffe JJ. Neurofibromatosis: clinical presentations and anaesthetic implications. Br J Anaesth. 2001;86:555-64. [ Links ]

6. Orozco Ariza JJ, Besson A, Pulido Rozo M, Ruiz Roca JA, Linares Tovar, Sáez Yuguero MaR. Neurofibromatosis tipo 1 (NF1) revisión y presentación de un caso clínico con manifestaciones bucofaciales. Av Odontoestomatol. 2005;21:5. [ Links ]

7. Mulvihill JJ, Parry DM, Sherman JL, Pikus A, Kaiser-Kupfer MI, Eldridge R. NIH conference: neurofibromatosis 1 (Recklinghausen disease) and neurofibromatosis 2 (bilateral acoustic neurofibromatosis). An update Ann Internal Med. 1990;113:39-52. [ Links ]

8. Gutmann DH, Aylsworth A, Carey JC, Korf B, Marks J, Pyeritz RE, et al. The diagnostic evaluation of multidisciplinary management of neurofibromatosis I and neurofibromatosis 2. JAMA. 1997;278:51-7. [ Links ]

9. Kloots RT, Rufini V,Gross MD, Shapiro B. Bone scans in neurofibromatosis: Neurofibroma, plexiform neurofibroma a neurofibrosarcoma. J Nucl Med. 1996;37:1778-83. [ Links ]

10. Weistler OD, Radner H. Pathology of neurofibromatosis I and 2. In: Huson SM, Hughes RAC, editors. The Neurofibromatoses. London: Chapman and Hall; 1994. p. 135-9. [ Links ]

11. Loh KC, Shlossberg EC, Abbot EC, Salisbury SR, Tah MH. Phaeochromocytoma: a ten year survey. Q J Med. 1997;90:51-60. [ Links ]

12. Sakai M, Vallejo MC, Shannon KT. A parturient with neurofibromatosis type 2: anesthetic and obstetric considerations for delivery. Inter J Obst Anesth. 2005;14:332-5. [ Links ]

13. Klein A, Clemens J, Cameron J. Periampullary neoplasms in von Recklinghausen disease. Surgery. 1989;106:815-9. [ Links ]

14. Ugren EB, Kinnear-Wilson LM, Stiller CA. Gliomas in neurofibromatosis: a series of 89 cases with evidence of enhanced malignancy in associated cerebellar astrocytomas. Pathol Annu. 1985;20:331-58. [ Links ]

15. Adams C, Fletcher WA, Myles ST. Chiasmal glioma in neurofibromatosis tipe I with severe visual loss regained with radiation. Pediatr Neurol. 1997;17:80-2. [ Links ]

16. Desai A, Carvalho B, Hansen J, Hill J. Ultrasound-guided popliteal nerve block in a patient with malignant degeneration of neurofibromatosis 1. Case Rep Anesthesiol. 2012 [Epub] [ Links ].

17. Sahin A, Aypar U. Spinal anesthesia in a patient with neurofibromatosis. Anesth Analg. 2003;97:1855-6. [ Links ]

18. Dounas M, Mercier FJ, Lhuissier C, Benhamou D. Epidural analgesia for labour in a parturient with neurofibromatosis. Can J Anaesth. 1995;42:420-4. [ Links ]

19. Triplett WW, Ondrey J, McDonald JS. Case report: anesthetic considerations in von Recklinghausen's disease. Anesth Prog. 1980;27:63. [ Links ]

20. Alcala-Cerra G, Moscote-Salazar L, Lozano-Tagua CF, Sabogal-Barrios R. Neumotórax espontáneo asociado a fibrosis pulmonar en un paciente con neurofibromatosis tipo 2. Rev Fac Med [online]. 2010;58:137-41. ISSN 0120-0011. [ Links ]

21. Richardson MG, Setty GK, Rawoof SA. Responses to non-depolarizing neuromuscular blockers and succinylcholine in von Recklinghausen neurofibromatosis. Anesth Analg. 1996;82:382-5. [ Links ]

text in

text in