Services on Demand

Journal

Article

Indicators

-

Cited by SciELO

Cited by SciELO -

Access statistics

Access statistics

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in

SciELO

Similars in

SciELO -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Colombian Journal of Anestesiology

Print version ISSN 0120-3347

Rev. colomb. anestesiol. vol.45 no.1 Bogotá Jan./June 2017

Postoperative residual curarization at the post-anesthetic care unit of a university hospital: A cross-sectional study☆

Relajación residual posoperatoria en la unidad de cuidados postanestésicos de un hospital universitario: Estudio de corte transversal

Fredy Arizaa,b,*, Fabián Doradoa, Luis E. Enríquezb, Vanessa González13, Juan Manuel Gómezb,c, Katheryne Chaparro-Mendozaa, Ángela Marulandaa, Diana Duránb, Reinaldo Carvajalc, Alex Humberto Castro-Gómezb, Plauto Figueroab, Hugo Medina3

a Anesthesiology and perioperative medicine, Fundación Valle del Lili, Cali, Colombia

b Department of Anesthesiology, Hospital Universitario del Valle, Universidad del Valle, Cali, Colombia

c Anesthesiology Service, Centro Médico Imbanaco, Cali, Colombia

☆ Please cite this article as: Ariza F, Dorado F, Enríquez LE, González V, Gómez JM, Chaparro-Mendoza K, et al. Relajación residual posoperatoria en la unidad de cuidados postanestésicos de un hospital universitario: Estudio de corte transversal. Rev Colomb Anestesiol. 2017;45:15-21.

* Corresponding author at: Fundación Valle del Lili, Av. Simón Bolívar, Cra 98, No. 18-49, Cali, Colombia.

E-mail address: fredyariza@hotmail.com (F. Ariza).

Article history:

Received 22 October 2015 Accepted 3 August 2016 Available online 25 November 2016

Abstract

Introduction: Postoperative residual curarization has been related to postoperative complications.

Objective: To determine the prevalence of postoperative residual curarization in a university hospital and its association with perioperative conditions.

Method: A prospective registry of 102 patients in a period of 4 months was designed to include ASA I-II patients who intraoperatively received nondepolarizing neuromuscular blockers. Abductor pollicis response to a train-of-four stimuli based on accelleromyography and thenar eminence temperature (TOF-Watch SX®. Organon, Ireland) was measured immediately upon arrival at the postanesthetic care unit and 30 s later. Uni-bivariate analysis was planned to determine possible associations with residual curarization, defined as two repeated values of T4/T1 ratio <0.90 in response to train-of-four stimuli.

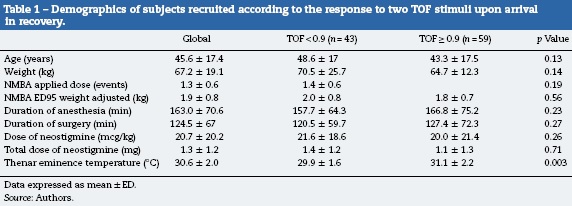

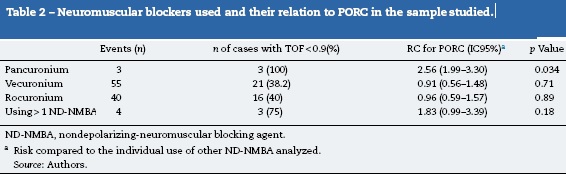

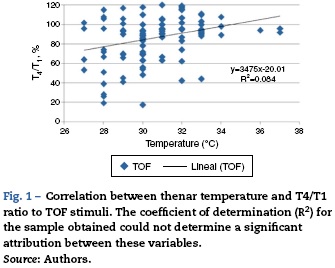

Results: Postoperative residual curarization was detected in 42.2% of the subjects. Pancuronium was associated with a high risk for train-of-four response <0.9 at the arrive at postoperative care unit [RR:2.56 (IC95% 1.99-3.30); p = 0.034]. A significant difference in thenar temperature (°C) was found in subjects with train-of-four <0.9 when compared to those who reach adequate neuromuscular function (29.9 ± 1.6 vs. 31.1 ± 2.2; respectively. p = 0.003). However, we were unable to demonstrate a direct attribution of findings in train-of-four response to temperature (R2 determination coefficient = 0.08%).

Conclusions: A high prevalence of postoperative residual curarization persists in university hospitals, despite a reduced use of "long-lasting" neuromuscular blockers. Strategies to assure neuromuscular monitoring practice and access to therapeutic alternatives in this setting must be considered. Intraoperative neuromuscular blockers using algorithms and continued education in this field must be priorities within anesthesia services.

Keywords: Neuromuscular blocking agents, Anesthesia, Perioperative period, Prevalence, Delayed emergence from anesthesia.

Resumen

Introducción: La relajación residual postoperatoria ha sido asociada con mayores complicaciones postoperatorias.

Objetivo: determinar la prevalencia de relajación residual postoperatoria en un hospital universitario y su relación con condiciones perioperatorias.

Métodos: Se diseñó un registro prospectivo de 4 meses de duración, que incluyó pacientes ASA I-II que intraoperatoriamente recibieran bloqueadores neuromusculares. Se registró la respuesta del abductor pollicis a un estímulo de tren de cuatro mediante aceleromiografía y se midió la temperatura de la eminencia tenar (TOF-Watch SX®.Organon, Ireland) inmediatamente al ingreso a recuperación y a los 30 segundos. Se realizó análisis uni y bivariado para determinar posibles asociaciones con relajación residual postoperatoria, definida como dos respuestas sucesivas al estímulo tren-de-cuatro con una relación T4/T1 <0.90.

Resultados: Se reclutaron 102 pacientes, encontrando una prevalencia de relajación residual del 42.2%. Pancuronio fue asociado con un riesgo elevado de TOF < 0.9 al ingreso a recuperación [RR:2,56 (IC95% 1.99-3.30); p = 0.034]. Se evidenció una diferencia significativa en la temperatura tenar de los pacientes que presentaban relajación residual, al compararla con pacientes que recuperaron su función neuromuscular [Grupo evento = 29.9 ± 1.6 (n = 43); Grupo control = 31.1 ±2.2 (n = 59)]. Sin embargo no se logró determinar una atribución directa de relajación residual a esta medición (coeficiente de determinación = 0.08%).

Conclusión: Persiste una alta prevalencia de relajación residual postoperatoria en los hospitales universitarios, a pesar del uso reducido de bloqueadores neuromusculares de larga duración. Se hace indispensable encaminar estrategias para incentivar la monitoria neuromuscular y establecer algoritmos que permitan un manejo eficiente de los bloqueadores neuromusculares.

Palabras clave: Bloqueantes neuromusculares, Anestesia, Periodo Perioperatorio, Prevalencia, Retraso en el despertar posanestésico.

Introduction

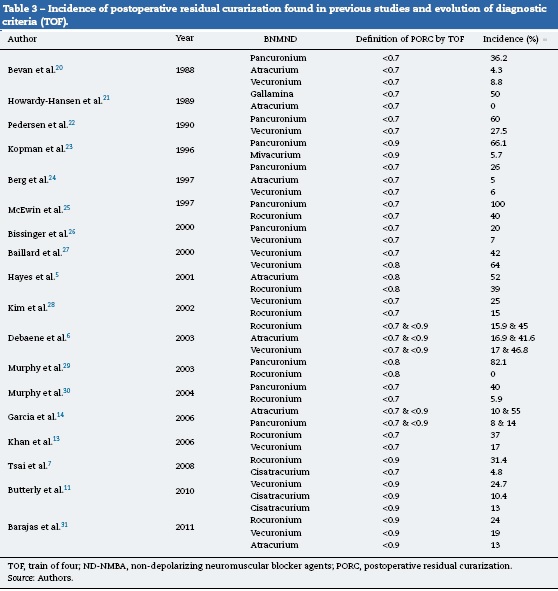

Nondepolarizing neuromuscular blocking agents (ND-NMBA) have commonly used in surgical units to facilitate endotracheal intubation and during procedures under general anesthesia to provide adequate surgical conditions or optimize ventilatory support. Postoperative residual curarization (PORC), defined as the presence of T4/T1 ratio <0.9 ratio in response to the "train-of-four" (TOF) stimulation,1-3 has been subject of multiple publications over the past three decades with a incidence reported up to 40%, even when the cut-off of TOF ratio to define PORC was as low as <0.7.4-9

The value of TOF ratio < 0.9, to define PORC, was recommended after papers wich reported that, below this cutoff, functional recovery of the laryngeal muscles and upper esophagus were not complete, even if the patient were holding ventilation in normal limits and overcoming clinical tests.3,10 Subsequent reports showed that rates of TOF < 0.9 were associated with longer lenght of stay in the Post Anesthesia Care Unit (PACU).11,12 This adverse event is stillbeingpresent today, even with the use of intermediate acting ND-NMBA or use of drugs such as neostigmine for reversing neuromuscular block.7,13-15 In Latin America there is a poor clinical applicability of neuro-muscular relaxation monitoring (NMRM) as well as in the rest of the world.16

This study aimed to assess the prevalence of PORC on admission to the PACU of patients treated at a university hospital as our primary objective, and to determine possible associations with demographic aspects and perioperative variables.

Materials and methods

Prior institutional ethics approval, a prospective observational registry of patients ASA I and II >18 years undergoing elective or emergency surgery under general anesthesia (in whom the use of ND-NMBA be envisaged) was designed. The size of the representative sample of the surgical population was defined and data were collected continuously during business hours during the time in which the expected number of patients was completed. All patients were invited to participate and gave their consent at admission to the surgical unit. Subjects with previous diagnosis of neurological or neuromuscular disease, those who were transferred to other places different to PACU or who requiring postoperative mechanical ventilation, were excluded.

At the end of surgery, an independent observer registered information on demographics, type of procedure and perioperative time, ND-NMBA used (type, total dose and method of administration), use of neostigmine (dose), use or not of NMRM and the result of TOF tests performed on admission to PACU.

A second-year resident of Anesthesiology or technical assistant previously trained and blinded to perioperative management were responsible to perform NMRM immediately for admission to PACU and 30 s later. TOF-Watch SX® (Organon, Ireland) acceleromyographic monitor was used, in order to evaluate the response of the adductor pollicis muscle. After cleaning the site, an electrode (distal) was positioned at the point where the proximal flexor line of the wrist crosses the radial side of the flexor carpi ulnaris; the proximal electrode was placed 3-Icm away from the first one, on the ulnar nerve area. Simultaneously, surface temperature was determined by a sensor placed on the thenar eminence. The TOF test was applied by four stimuli of 0.2milliseconds (ms) duration at 2 Hz and at 30 mA.17,18 After 30 s the test was repeated and registered; if incongruities were detected, a third test, was performed after 60 s.

PORC was defined as the presence of a T4/T1 ratio < 0.90 ratio in response to the TOF test.3,10 Procedure was validated based on the evaluation of the interrate reliability (20% of the sample). In regards to the test and results, the anesthesiologist remained blinded to control the treatment bias.

Statistic analysis

Sample size was calculated based on a reported incidence of PORC around 35% to detect a confidence level of 95% and a power of 80%. An estimate of 95 subjects were decided to include after adjusting for possible losses by 15%. The prevalence of the outcome of interest was calculated as follows:

number of patients with PORC on the number of patients ASA I and II, who undergoing emergency or elective surgery, requiring NMBA in the established period (4 months). Processing and data analysis was performed using SPSS 20.0 (SPSS Statistics for Windows, version 20.0. Armonk, NY). Categorical variables are described as proportions and percentage distributions while numerical variables as means and standard deviations (SD). Differences among groups were evaluated based on analysis of variance of one way. Significance level α < 0.05 was set a priori. Concordance analysis was performed with the MedCalc® (Mariakerke, Belgium, http://www.medcalc.be) software.

Results

A total of 102 subjects accepted to participate in this study. Procedures included: general surgery (33.3%), head and neck (16.7%), gynecology (14.7%), orthopedics (12.7%) and other (13.7%). Only the temperature (°C), recorded in the thenar eminence on arrival in PACU, was significantly lower in patients with TOF<0.90 (29.9 ±1.6 vs. 31.1 ±2.2; p = 0.003). Other demographic characteristics related to surgery showed no differences between groups (Table 1).

Vecuronium (53.9%), rocuronium (39.2%) and pancuronium (3%) were the ND-NMBA used in this sample. At the end of procedure none of the subjects received cyclodextrins or ND-NMBA (benzylisoquinolinics) while the use of more than one ND-NMBA was observed in 4 of the cases. When exploring for a possible causality between PORC and type of ND-NMB used, it was found that the use of pancuronium was significantly associated with this outcome: [RR 2.56 (95% CI 1.99-3.30); p = 0.034]. Additionally, a non-significant trend to increased cases of PORC was found when combinations of these drugs (Table 2) were presented.

The reversal of neuromuscular blockade was performed in 57% of patients and in all cases neostigmine was used at doses between 20 and 25mcg/kg. No significant differences were found when analyzed whether its application was associated with decreased incidence of TOF < 0.90 on arrival in PACU. Similarly no relationship between the use of NMRM and a significant decrease of PORC was found.

To clarify the influence of the temperature measured in the thenar eminence on the TOF test results, we performed a concordance analysis. Coefficient of determination (R2) showed a value of 0.08%, indicating that the results obtained in the TOF test could not attributed at least completely by this factor (Fig. 1).

Discussion

PORC incidence reported in our study was 42.2%, similar to that reported in previous publications (Table 3), despite the widespread use of intermediate-acting ND-NMBA figure. We would like to highlight the use of doses close to DE95x2 in the sample analyzed and a total preference for the use of ND-NMBA of steroid type, whereas a global trend is toward the use of lower doses of these drugs and a reduction of their use only for selected cases. Our data show that pancuronium is associated with a greater probability of PORC as reported by previous studies.19 Although the sample size of our study does not allow us to make greater assertions, we believe there is a greater likelihood of adverse events related to the combined use of more than one ND-NMBA.

We believe our results may be due to multiple factors. In the first instance, there are barriers on awareness to prevent and detect this adverse event within anesthesia teams this adverse event. Additionally, the absence of other therapeutic alternatives such as benzylisoquinolinics, which have been associated with a lower incidence of PORC and interindividual variability,32,33 limits the staff practicing in public hospitals, unable to decide between different current therapeutic options in diverse clinical scenarios. Nevertheless and as shown by our results, a proportionally smaller pancuronium use has been observed. We estimate a further reduction in the use of this drug for the coming years, as usual option in operating rooms.

It has been suggested that routine use NMRM intraoperatively, could reduce the incidence of PORC,34 and thus decrease complications associated with this morbid condition. It is well known that clinical tests as elevation of the head or feet, evaluation of minute volume among others, have a poor positive predictive value for detecting PORC.5,17 Even in the case of acceleromyography (considered the current standard of care for NMRM), there is a significant variability that does not fully rule out PORC even under optimal conditions for its measurement.18,30 This fact, together with the high degree of interindividual variation in the response and time effect against equipotent doses of ND-NMBA reinforce our recommendation of not only encourage the use of NMRM, but a need to implement institutional protocols for the management of ND-NMBA in ICU35 and operating rooms as places where a large number of factors negatively influence the predictability of the clinical response to these drugs.

Our finding about the correlation between lower thenar temperatures and a higher proportion of PORC deserves further analysis. A failed statistical causality between these temperatures (coefficient of determination) and the main event can be explained by the high variability between central temperatures and peripheral areas.36 However, we believe that lower temperatures found in the group with a TOF ratio < 0.9 may represent a higher proportion of intraoperative hypothermia in this group, which has been directly related to prolonged effect of NMB.9,14

This study represents one of the first publications in Latin America in order to delimit this problem at public university hospitals14,32,37; scenarios where limitations in alternative therapies and devices for monitoring and preservation of homeostasis during surgery are frequent. Similarly, the approaches and routines in NMB dosage, NMRM use and reversal of NMB are heterogeneous as shown our results. However, we must recognize important limitations in this report since aspects such as missed data of core temperatures for the subjects after surgery, the exact timing of NMB reversal (when this was performed) or ensuring a temperature above 32 °C in the member assessed, could not be dealt with. In regards to standardization of TOF test arrival upon PACU, we follow the guidelines for NMRM, considering that the voltages used in our study are valid for the evaluation of neuromuscular function for awake patiens.38

Conclusions

Current prevalence of PORC in a Latin American university hospital representative of other institutions in the area, is as high as reported by similar studies around the world. Despite an apparent reduction in the use of long lasting ND-NMBA an unacceptably high incidence of this adverse event persists. Although this study failed to show a clear association between hypothermia and PORC, we considered that the absence of thermal protection strategies could be a precipitant factor related to ND-NMBA problems in PACU. Given the high prevalence of this problem, we strongly suggest to enhance strategies to stimulate the routine practice of NMRM in public hospitals and efforts to assure availability of different therapeutic options for this purpose, as well as to encourage surgical teams to build ND-NMBA using algorithms in order to offer the best possible perioperative care to our patients.

Ethical disclosures

Protection of human and animal subjects. The authors declare that the procedures followed were in accordance with the regulations of the relevant clinical research ethics committee and with those of the Code of Ethics of the World Medical Association (Declaration of Helsinki).

Confidentiality of data. The authors declare that they have followed the protocols of their work center on the publication of patient data.

Right to privacy and informed consent. The authors declare that no patient data appear in this article.

Financing

The authors did not receive sponsorship to carry out this article.

Conflicts of interest

The authors report that they have no conflict of interest.

References

1. Kopman AF, Yee PS, Neuman GG. Relationship of the train-of-four fade ratio to clinical signs and symptoms of residual paralysis in awake volunteers. Anesthesiology. 1997;86:765-71. [ Links ]

2. Viby-Mogensen J. Postoperative residual curarization and evidence-based anaesthesia. Br J Anaesth. 2000;84:301-3. [ Links ]

3. Mathias LAST, Bernardis RCG. Parálisis residual postoperatoria. Rev Brass Anestesiol. 2012;62:439-50. [ Links ]

4. Viby-Mogensen J, J0rgensen BC, Ording H. Residual curarization in the recovery room. Anesthesiology. 1979;50:539-41. [ Links ]

5. Hayes AH, Mirakhur RK, Breslin DS, Reid JE, McCourt KC. Postoperative residual block after intermediate-acting neuromuscular blocking drugs. Anaesthesia. 2001;56:312-8. [ Links ]

6. Debaene B, Plaud B, Dilly M-P, Donati F. Residual paralysis in the PACU after a single intubating dose of nondepolarizing muscle relaxant with an intermediate duration of action. Anesthesiology. 2003;98:1042-8. [ Links ]

7. Tsai C-C, Chung H-S, Chen P-L, Yu C-M, Chen M-S, Hong C-L. Postoperative residual curarization: clinical observation in the post-anesthesia care unit. Chang Gung Med J. 2008;31:364-8. [ Links ]

8. Murphy GS. Residual neuromuscular blockade: incidence, assessment, and relevance in the postoperative period. Minerva Anestesiol. 2006;72:97-109. [ Links ]

9. Murphy GS, Brull SJ. Residual neuromuscular block: lessons unlearned. Part I: definitions, incidence, and adverse physiologic effects of residual neuromuscular block. Anesth Analg. 2010;111:120-8. [ Links ]

10. Eriksson LI. The effects of residual neuromuscular blockade and volatile anesthetics on the control of ventilation. Anesth Analg. 1999;89:243-51. [ Links ]

11. Butterly A, Bittner EA, George E, Sandberg WS, Eikermann M, Schmidt U. Postoperative residual curarization from intermediate-acting neuromuscular blocking agents delays recovery room discharge. Br J Anaesth. 2010;105:304-9. [ Links ]

12. Naguib M, Kopman AF, Ensor JE. Neuromuscular monitoring and postoperative residual curarisation: a meta-analysis. Br J Anaesth. 2007;98:302-16. [ Links ]

13. Khan S, Divatia JV, Sareen R. Comparison of residual neuromuscular blockade between two intermediate acting nondepolarizing neuromuscular blocking agents-rocuronium and vecuronium. Indian J Anaesth. 2006;50:115-7. [ Links ]

14. García MP, Sergi N, Finkel DM. Incidencia de bloqueo neuromuscular residual al ingreso en la unidad de recuperación postanestésica. Rev argent anestesiol. 2006;64:121-9. [ Links ]

15. Lema Flórez E, Tafur LA, Lucía Giraldo A. Aproximación al conocimiento de los hábitos que tienen los anestesiólogos en el uso de relajantes neuromusculares no despolarizantes y sus reversores, Valle del Cauca, Colombia. Rev Colomb Anestesiol. 2012;40:113-8. [ Links ]

16. Reyes L, Muñoz L, Orozco D, Arias C, Vergel V,Valencia A. Variabilidad clínica del vecuronio. Experiencia en una institución en Colombia. Rev Colomb Anestesiol. 2012;40:251-5. [ Links ]

17. Brull SJ, Murphy GS. Residual neuromuscular block: lessons unlearned. Part II: methods to reduce the risk of residual weakness. Anesth Analg. 2010;111:129-40. [ Links ]

18. Helbo-Hansen HS, Bang U, Nielsen HK, Skovgaard LT. The accuracy of train-of-four monitoring at varying stimulating currents. Anesthesiology. 1992;76:199-203. [ Links ]

19. Taylor NAS, Tipton MJ, Kenny GP. Considerations for the measurement of core, skin and mean body temperatures. J Therm Biol. 2014;46:72-101. [ Links ]

20. Bevan DR, Smith CE, Donati F. Postoperative neuromuscular blockade: a comparison between atracurium, vecuronium, and pancuronium. Anesthesiology. 1988;69:272-6. [ Links ]

21. Howardy-Hansen P, M0ller J, Hansen B. Pretreatment with atracurium: the influence on neuromuscular transmission and pulmonary function. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 1987;31:642-4. [ Links ]

22. Pedersen T, Viby-Mogensen J, Bang U, Olsen NV, Jensen E, Engboek J. Does perioperative tactile evaluation of the train-of-four response influence the frequency of postoperative residual neuromuscular blockade? Anesthesiology. 1990;73:835-9. [ Links ]

23. Kopman AF, Ng J, Zank LM, Neuman GG, Yee PS. Residual postoperative paralysis. Pancuronium versus mivacurium, does it matter? Anesthesiology. 1996;85:1253-9. [ Links ]

24. Berg H, Roed J, Viby-Mogensen J, Mortensen CR, Engbaek J, Skovgaard LT, et al. Residual neuromuscular block is a risk factor for postoperative pulmonary complications. A prospective, randomised, and blinded study of postoperative pulmonary complications after atracurium, vecuronium and pancuronium. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 1997;41:1095-103. [ Links ]

25. McEwin L, Merrick PM, Bevan DR. Residual neuromuscular blockade after cardiac surgery: pancuronium vs. rocuronium. Can J Anaesth. 1997;44:891-5. [ Links ]

26. Bissinger U, Schimek F, Lenz G. Postoperative residual paralysis and respiratory status: a comparative study of pancuronium and vecuronium. Physiol Res. 2000;49:455-62. [ Links ]

27. Baillard C, Gehan G, Reboul-Marty J, Larmignat P, Samama CM, Cupa M. Residual curarization in the recovery room after vecuronium. Br J Anaesth. 2000;84:394-5. [ Links ]

28. Kim KS, Lew SH, Cho HY, Cheong MA. Residual paralysis induced by either vecuronium or rocuronium after reversal with pyridostigmine. Anesth Analg. 2002;95:1656-60. [ Links ]

29. Murphy GS, Szokol JW, Marymont JH, Vender JS, Avram MJ, Rosengart TK, et al. Recovery of neuromuscular function after cardiac surgery: pancuronium versus rocuronium. Anesth Analg. 2003;96:1301-7. [ Links ]

30. Murphy GS, Szokol JW, Franklin M, Marymont JH, Avram MJ, Vender JS. Postanesthesia care unit recovery times and neuromuscular blocking drugs: a prospective study of orthopedic surgical patients randomized to receive pancuronium or rocuronium. Anesth Analg. 2004;98:193-200. [ Links ]

31. Barajas R, Camarena J, Castellanos A, Castilleros OA, Castorena G, de Anda D, et al. Determinación de la incidencia de la parálisis residual postanestésica con el uso de agentes bloqueadores neuromusculares en méxico. Rev Mex Anestesiol. 2011;34:181-8. [ Links ]

32. Fabregat López J, Candia Arana CA, Castillo Monzón CG. La monitorización neuromuscular y su importancia en el uso de los bloqueantes neuromusculares. Re Colomb Anestesiol. 2012;40:293-303. [ Links ]

33. Arain SR, Kern S, Ficke DJ, Ebert TJ. Variability of duration of action of neuromuscular-blocking drugs in elderly patients. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 2005;49:312-5. [ Links ]

34. Pühringer FK, Heier T, Dodgson M, Erkola O, Goonetilleke P, Hofmockel R, et al. Double-blind comparison of the variability in spontaneous recovery of cisatracurium- and vecuronium-induced neuromuscular block in adult and elderly patients. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 2002;46:364-71. [ Links ]

35. Ariza Cadena F. Estrategias para disminuir los eventos adversos más frecuentes relacionados con bloqueadores neuromusculares. Rev Colomb Anestesiol. 2012;40:127-30. [ Links ]

36. Murphy GS, Szokol JW, Marymont JH, Greenberg SB, Avram MJ, Vender JS, et al. Intraoperative acceleromyographic monitoring reduces the risk of residual neuromuscular blockade and adverse respiratory events in the postanesthesia care unit. Anesthesiology. 2008;109:389-98. [ Links ]

37. Rincón PG. Incidencia de bloqueo neuromuscular residual en recuperacion con relajantes de accion intermedia en la practica diaria. Rev Colomb Anestesiol. 1999;27:309-17. [ Links ]

38. Van Oldenbeek C, Knowles P, Harper NJ. Residual neuromuscular block caused by pancuronium after cardiac surgery. Br J Anaesth. 1999;83:338-9. [ Links ]

text in

text in