Introduction

This article submits an analysis of the social representations of pain of a IV level hospital medical staff in Bogotá, Colombia, dwelling on the way these representations are used to interpret and take action in the management of pain.

In the middle of the 20th century, John Bonica and Cicely Saunders, among others, initiated a new approach to study and adopt a differential pain management strategy, providing care and intervening based on the precise organic source of pain and according to the patient's particular psychological and social characteristics.1 This led to the consideration of forms of pain that had been neglected or underestimated so far, including postoperative and chronic pain in terminal patients.2 These new approaches understand pain as an "agonizing experience associated with real or potential tissue damage, with emotional, sensory, cognitive and social components"- consistent with the definition suggested by IASP in 2016.3

The expression and understanding of pain poses a 2-fold difficulty, since the pain phenomenon involves communication problems in the light of 2 subjective appreciations-the patient experiencing the pain and the person receiving the complaint.4,5 Pain is also an emotion6,7 and thus its existence is difficult to prove and its intensity is hard to measure.6,8

Furthermore, pain is a social phenomenon since it is perceived from cultural benchmarks,9-13 from which the patient attempts to communicate his/her experience and the health professional tries to identify and understand the scope of such experience.14 The difficulty in managing pain is that usually subjectivity and the personal and individual experience are underestimated,15 while biological or strictly medical factors are overestimated.16 All of these factors lead to a dissimilar understanding and evaluation of pain between the patient and the healthcare staff,17 resulting in poor management. Consequently, a qualitative study of the problem is indispensable to understand communication issues between patients and care providers.18

The challenges of the new study paradigm and pain management initiated by Saunders and Bonica and restated in the IASP proposals, do not simply require changing the knowledge of the physician and the healthcare team,19 but a transformation of the communication and understanding of pain within the framework of the believes, preconceptions, stereotypes, and imaginary of the healthcare staff versus the "painful behavior."20-22

Materials and methods

This research is based on Moscovici's23 theory of social representations that describes the way people learn from the events and information in his/her environment.24 Social representations are made up of words and actions emerging from narratives comprising secular and official discourse.25,26

The objective of this paper is to identify in the discourse and behavior of the healthcare professionals in a hospital, the way in which they welcome and interpret pain manifestations to guide their attitude toward their patients.

The results show that social representations of pain are not exclusively restricted to the concepts and protocols formalized in the scientific debate or in the hospital institution,27,28 but they coexist with laymen theories and subjective benchmarks.

This is a qualitative descriptive cross-section study for which 2 data collection techniques were used: (n = 45) semi-structured interviews that included the use of natural semantic networks (NSN) whereby patients were asked to list 5 words (evocations) to define pain and organize them in terms of their perceived relevance. The NSNs allow for tracking the representations that people make of a particular term by social groups.29 Additionally, a non-participant observation was made over 6 months, which was registered in a field diary that included attitudes, behaviors, and expressions associated with pain and the care of patients in pain.

The interviewees were key informants of the institution. The interviews were recorded, transcribed and then analyzed using the Atlas-ti 6 software to visualize the most relevant elements.

This research was approved by the ethics committee of Universidad del Rosario, classified as a low-risk research on March 9, 2015, under memorandum 281 and reference number CEI- ABN026-000070.

Data analysis

The data collected and the NSN were organized into semantic nodes to enable triangulation of the information.

The results of the SNS were a large number of descriptors mentioned by the participants (n = 88). These were classified in 2 ways: according to the profession and level of training of the individual mentioning the descriptor and based on semantics association; in other words, the descriptors were organized into sets of terms with equal meaning that represent the different perspectives to understand pain, defining 4 semantic nodes.

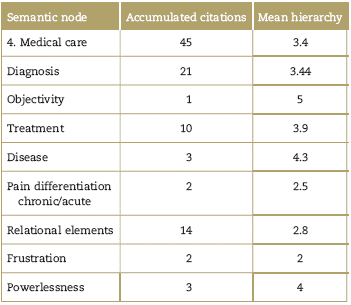

Node 1. Emotional and cognitive experience: includes terms regarding the effect on emotions and/or cognitive abilities (anxiety, sadness, distress, etc). Subcategories: mourning and loss, psychological factors, relational elements, and factors associated with experience) (Table 1).

Table 1 Emotional and cognitive experience.

Source: (NSN) extracted from the semi-structured interviews conducted by the project research team.

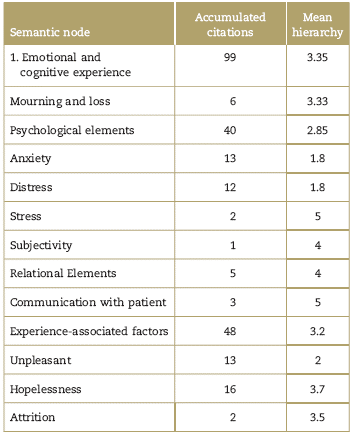

Node 2. Biological and sensory phenomenon: comprises terms associated with biological and sensory-perceptive elements of pain (alertness, perception, damage indicator, etc). Subcategories: sensory-perception, alertness mechanism, and pain effects (Table 2).

Table 2 Biological phenomenon.

Source: (NSN) extracted from the semi-structured interviews conducted by the project research team.

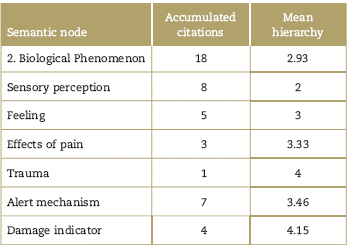

Node 3. Sociopolitical reality: comprises the terms referring to the social, political and economic reality of pain, both in the medical and patient context (fundamental right, cultural influence, vulnerability, isolation, etc). Subcategories: Political and economic aspects and cultural impact (Table 3).

Table 3 Sociopolitical reality.

Source: (NSN) extracted from the semi-structured interviews conducted by the project research team.

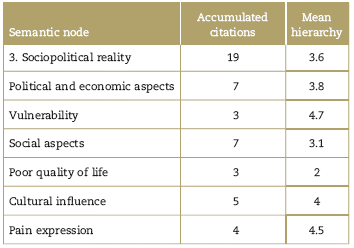

Node 4. Medical care: comprises terms relating to relational elements and terms referring to the experience of the medical practice (measurement difficulty, pain as a friend, multifactorial, etc), terms referring to intervention practices including the processes of pain evaluation, diagnosis, and treatment. Subcategories: diagnosis, treatment, and relational elements (Table 4).

Results

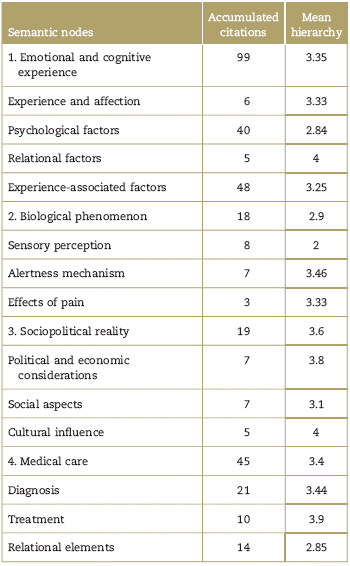

The following results (Table 5) indicate a prevalence of terms associated with the emotional experience (99 citations of these terms, with a hierarchical position of 3.35), followed by terms associated with medical care, the semantic node 4 (45 citations of terms, hierarchical position 3.4), followed by the semantic node regarding sociopolitical aspects of pain with 19 citations of terms, hierarchical position 3.6), and finally the semantic node 2 associated with the biological aspects of pain (18 citations, hierarchical position 2.9).

Table 5 Natural semantics network-pain.

Source: (NSN) extracted from the semi-structured interviews conducted by the project research team.

Continuing with the data collected in the field diary, a broad range of approaches to the understanding and treatment of pain was identified, depending on the hospital service, the level of education, the specialty, the experience and the dominant clinical objectives in each hospital and clinical specialty. Despite this considerable diversity, there is apparently a trend to underestimate the subjective aspects of pain. In this sense, the clinical staff tends to see pain as a rather uncomfortable manifestation of the patient's subjectivity. Notwithstanding the efforts made in this hospital, using the virtual course "Change Pain" as a primary training tool and with an intervention in the design of protocols, the health professionals continue to systematize the diagnosis of pain with a reductionist approach, usually guided by the clinicians need to identify progress indicators in patients. Although there is interest in providing adequate pain care, the work teams still lack a comprehensive coordination.

Discussion

There was a marked trend to define pain based on elements referring to experiencing anxiety and distress (mostly node 1 categories), where communication with the patient turns difficult. An unpleasant experience with the potential to develop frustration that leads to emotional exhaustion of the clinical staff. A second factor highlighted in the NSN is the importance given to medical care of pain, focusing on a clear concern for the diagnosis and for objectivity. It is a concern for achieving an acceptable level of certainty in the identification of pain, using means different from the patient's report which generates mistrust (node 4), notwithstanding the fact that contemporary theory considers self-reporting as an essential component of the evaluation. On the other hand, although the biological (node 2), social and cultural components (node 3) are part of the pain perspective, these were less emphasized in the definition.

The NSN indicates a prevalence of the categories related to the emotional and cognitive aspects of pain. However, when comparing against the more comprehensive contents of the interviews, it is difficult to identify to whom these emotions belong. When healthcare professionals speak about anxiety, distress, inter alia, the emotional experiences of the professional are mixed up with the patient's emotions. Nevertheless, notwithstanding this situation, the fieldwork showed that the clinical staff often tends to ignore the patient's affective behavior and rather focus on the technical aspects of their job. Being less concerned about the patient's distress is a frequent reaction in situations where emotions are overex-pressed-particularly anxiety as a result of suffering- perceived as an awkward and even hazardous experience for the individual's psychological integrity.30

In the hospital, the scenarios where particular attention is given to the subjectivity of the discomfort are particular instances of pain clinic care, physical therapy, and the care provided but some residents and medical interns. Notwithstanding the fact that there is an official statement regarding efficient and appropriate pain care, there are limited resources available to the clinical staff to provide psychological support and to communicate with the patient. Likewise, there is limited opportunity for an interdisciplinary approach to pain by the clinical staff or for efficient communication. Finally, despite institutional efforts, the resources available to the clinical staff are still extremely limited to protect themselves psychologically from difficult interactions.

There is a difficult to interpret relational component. It seems to be quite relevant in node 4 (14 citations with a mean hierarchy of 2.8). However, in node 1 (Table 1)the terms referring to relationships are considerably less relevant (5 citations with a mean hierarchy of 4). From the SNS perspective and based on the analysis of the interviews, the clinicians have a poor understanding of the impact of emotions on the development and functionality of relationships. In terms of dealing with the patient, among the clinicians it is difficult to establish a therapeutic relationship based on the eagerness to achieve immediate results. Clinicians prefer to have control over therapy and therefore they adopt a hierarchical position versus the patient, and the patient's emotions are only considered to legitimize the hierarchical relationship between the patient and the clinician. Thus, relationships are more relevant in medical care based on a hierarchical relation where the clinician holds the truth about the patient's illness and pain.

The lack of interest or ignorance of the participants about the technical aspects of the source and management of pain as a biological and sensory phenomenon account for the poor appropriation of knowledge and approaches of what we have called the "new paradigm," in addition to the prevalence of laymen or obsolete theories about the clinical management of pain. There is a marked trend toward misleading information of the nursing staff, that usually defines pain with colloquial terms and attrition-associated ideas. This may be explained via the barriers to education of the clinical staff that hinder the expansion and the adoption of this new paradigm. Some of our key informants acknowledged that the high personnel turnover represented a loss of many of the lessons learned through the Change-pain program and through experience. Finally, the field diary evidenced the existence of institutional administrative, and economic issues where the shortage of staff, the focus on less subjective aspects of the disease, and the lack of time for listening to patients, sideline the interest of healthcare teams to adopt a comprehensive approach of the patient afflicted with pain.

The relevance of the "Pain Clinic" at the institutional level, established 10 years ago is worth noting. The perception of the hospital staff with regards to the work of this team is highly positive. However, quite often, the medical professionals use this team as a last resort, when all other options have been exhausted, but without necessarily transforming their own tools or enhanced their communication abilities and their understanding for providing better pain management. The challenge to the institution and for the professionals involved is to definitively anchor this new paradigm of understanding and managing pain in the institutional culture of the hospital. This will lead to enhanced comprehensive treatment of patients and to a dignified role of the hospital staff.

Ethical responsibilities

Protection of persons and animals: The authors declare that no experiments in humans or animals have been conducted for this research.

Confidentiality of data: The authors declare that all the protocols of their workplace have been followed in terms of disclosure of information of the subjects mentioned in the article (healthcare professionals working at the referred hospital).

Right to privacy and informed consent: The authors have obtained the informed consent of the subjects referred to in the article (healthcare professionals working at the referred hospital). This document is under custody of the corresponding author.

This research trial complies with the current Colombian regulations (resolution n° 008430 of 1993 of the Ministry of Health, and Law 1090 of 2006, whereby the job of the psychologist is regulated, with particular emphasis on Chapter VII under that Law). The protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Universidad del Rosario and by the Research Committee of the hospital where the study was conducted.

text in

text in