Introduction

Primary total knee arthroplasty (PTKA) is considered an effective alternative for managing severe knee joint disease.1-4 The most frequently associated diagnosis is osteoarthritis, 5 causing severe pain and decreased range of motion, limiting the patient's daily activities and impacting quality of life. 5-8 The prevalence of symptomatic osteoarthritis is up to 26% in women over 70 years old, and the knee is the most affected joint.9 Failure to conventional therapy and the level of quality of life disruption, associated with typical radiological signs, are the foundation to indicate the procedure. A method for measuring the presence and the severity of these factors is the Oxford scale, first described in 1998 by Dawson et al.10 This scale evaluates pain, function, quality of life, and interference of symptoms with daily activities.10 The scale is used for the initial evaluation of joint involvement and for postoperative follow-up.

Due to the aging population, a significant increase in the rate of PTKA has been identified in several countries around the world in the last few years. 7,10 According to Kurtz et al, 11 this number is expected to rise by 2030 by about 673%, accounting for 570,000 cases in the United States. At Fundación Valle del Lili, a high complexity medical center, approximately 15,000 surgeries are performed every year; the procedure was done 114 and 127 times in 2015 and 2016, respectively, clearly indicating a rising trend.

Despite the success of the procedure, a considerable proportion of patients present with persistent chronic osteoarticular postoperative pain12,13; this situation nega tively affects patient satisfaction in the long term. 14 For this reason, the participation of anesthesiology in the multidisciplinary team should be active and direct, intervening on the immediate and short-term management of analgesia in these patients,15 as severe post-surgical pain may add to the development of chronic postsurgical pain.

PTKA is challenging in terms of the management of anesthesia and analgesia; the most frequent candidates for this surgery are the elderly with advanced joint arthrosis, a tendency to be obese, and multiple comorbidities.16,17 Moreover, on the basis of clinical practice and directly patient-derived factors, the results of the immediate recovery in terms of the severity of the acute postoperative pain and compliance with the early physical rehabilitation guidelines are heterogeneous. The use of anesthetic techniques in this procedure shall be directed at achieving adequate postoperative control, with the lowest rate of side effects and minimal interference with the recovery process.10,18

Regional analgesia techniques as part of anesthetic management are an effective option for the prevention of moderate to severe postoperative pain,19 as long as these techniques are adapted to the recovery needs of the patient. Preserving muscle function to facilitate rehabilitation has been the main motivation to look for other alternatives to the conventional regional techniques such as continuous perineural infusion of local anesthetic agents through a femoral catheter and sciatic nerve block (CNB).20 The risk of falls, an additional concern in the management of these patients, has proven to be multi-factorial and not directly associated with the use of regional anesthesia (RA).21 Local periarticular infiltration22 and the adductor canal block (ACB)23 that avoid the quadriceps paralysis and the use of anti-hyperalgesia medications during the perioperative period24,25 are the current trend for analgesia management in these patients. Nowadays, the potential to administer RA as a standard technique, according to the recommendations of a number of scientific associations, depends on the availability of material and human resources that are competent enough to do the procedure safely and efficiently.5,10

In our daily clinical practice, the use of different multimodal analgesia techniques generates heterogeneous results in the evolution of symptoms in these patients, and probably in meeting the objectives of the intrahospital rehabilitation plan. This study was intended to characterize the population of patients undergoing PTKA with information collected from the medical records review on the clinical, anesthesia, and analgesia characteristics, over a 10-month period. The primary outcome measured was the incidence of moderate to severe postoperative pain at 24 and 48 hours, and the secondary outcome was the compliance with the rehabilitation plan by more than 50% and 70%.

Methods

In keeping with the standards of the World Health Organization (WHO) and the Pan American Health Organization (PAHO) for human subjects, supported by the declaration of Helsinki and the Scientific, Technical and Administrative Standards for Health Research, set forth under Resolution No. 008430 of 1993 of the Ministry of Health of Colombia, biomedical research shall be conducted abiding to the principles of respect for persons, welfare, and justice. In accordance with the risk categories established, and by not intervening directly with the participants, this study was considered risk-free and hence the informed consent was not used. This study was approved by the Ethics Committee in Institutional Medical Research and funded by Fundación Valle del Lili.

This is an observational, descriptive study of patients who underwent PTKA under the indication of the orthopedics department, from September 2016 until June 2017. Demographic and clinical information was collected from the medical records review in order to develop the database, using the evaluation by orthopedics and inter nal medicine, the pre-anesthesia evaluation, the anesthetic report, and the follow-up by the Acute Pain Clinic (APC), physiatry, and physical therapy. The anesthetic and analgesia technique was chosen at the discretion of the patient and the anesthesiologists in charge.

As a routine, the APC led by the anesthesiology service conducted the daily postoperative follow-up of these patients, evaluated the effectiveness of the analgesic regime in terms of pain severity, performance of basic recovery activities, and occurrence of any adverse effects, indicating any appropriate changes as required. The Numerical Rating Scale (NRS) was used for pain evaluation, with scores from 0 to 10, depending on the pain intensity reported, with 0 being no pain and 10 the worst imaginable pain. When the NRS scale could not be used, mostly because of the patient's lack of comprehension, the categorical pain scale, mild, moderate, severe, was used instead. To analyze this study, the pain descriptors were standardized against the NRS scale as follows: 1 to 3, mild; 4 to 6, moderate; and 7 to 10, severe, as validated in other postoperative pain studies.26 The analgesia technique used was considered effective if during the postoperative period, the patient presents with mild pain (or its equivalent in the NRS). The incidence of moderate to severe rest pain in the postanesthesia care unit (PACU) was estimated 24 and 48 hours after surgery, as a measure of effectiveness of the particular analgesia technique; this level of pain severity is an indication to make changes in the analgesia regime, mainly adding or increasing strong opioid use and/or adjuvants according to the institutional protocol, with the possibility of increased secondary adverse effects.

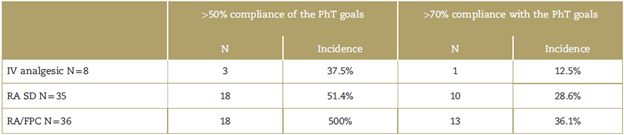

The results of the evaluation by the group of physiatry and physical therapy were collected; they measure compliance with the institutional early rehabilitation plan [pain modulation, passive knee extension at 0°, minimal knee flexion of 90°, active quadriceps contraction, transition training (supine decubitus to seated edge of bed and vice versa), externally assisted walking (walker), and patient and family education about the exercise plan and mobilization precautions] with a percentage score from 0% to 100%. The percentage of patients meeting over 50% and 70% of the intrahospital rehabilitation goals was estimated, in accordance with the analgesia technique used.

As a general rule, patients with missing information throughout their follow-up were excluded from the study. A total of 6 patients were followed by APC only over the first 24 postoperative hours. This corresponds to the difference observed for the 48-hour postoperative measurement of the total number of patients. Therefore, these are excluded from the analysis and the total number of patients for that measurement is adjusted.

Statistical analysis

The variables distribution was evaluated with the Shapiro-Wilk test. The measurements used were the central trend, the mean or the average, and as scatter measures, standard deviation (SD), and interquartile range (IQR), as appropriate. The categorical variables were presented as percentages.

The frequency of the anesthetic and analgesia techni ques was estimated in proportions, using each technique as a numerator and the total number of patients as the denominator. The categorical pain evaluation at the various time points of measurement was estimated as a proportion, using as a numerator the number of patients experiencing the event, and as the denominator the total number of patients in the study. The incidence of moderate to severe postoperative pain in the PACU at 24 and 48 hours based on the analgesic technique was estimated as a percentage taking the number of patients with moderate to severe pain as the numerator, and the total number of patients with each analgesic technique as the denominator. Similarly, the percentage of patients who met more than 50% and 70% of the rehabilitation goals with each analgesia technique was estimated. Frequency tables and bar charts showing the information collected were developed. The statistical analysis used Stata 14 software (StataCorp. 2015. Stata Statistical Software: Release 14. College Station, TX: StataCorp LP.).

Results

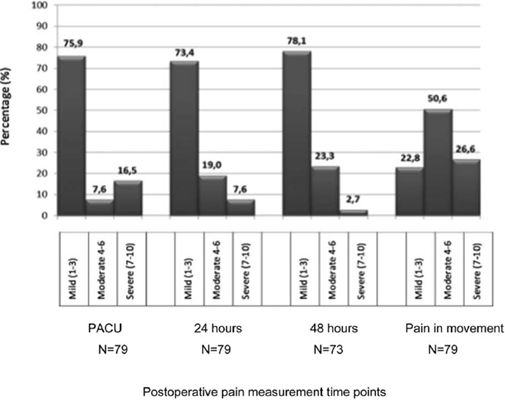

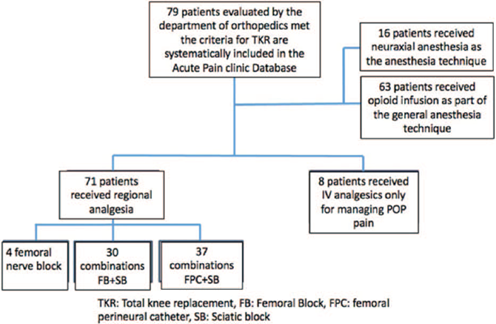

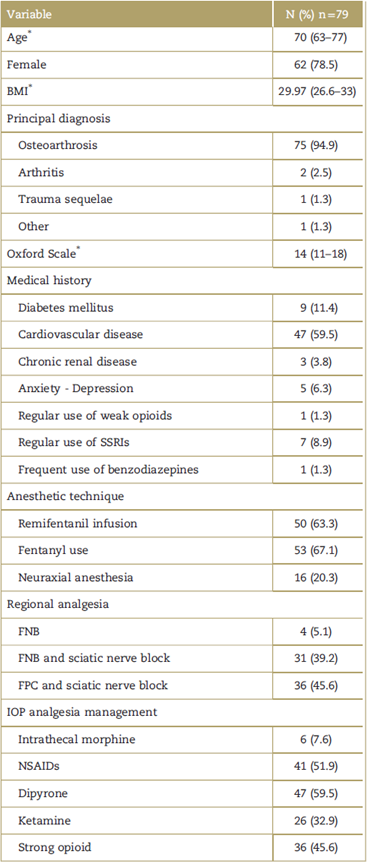

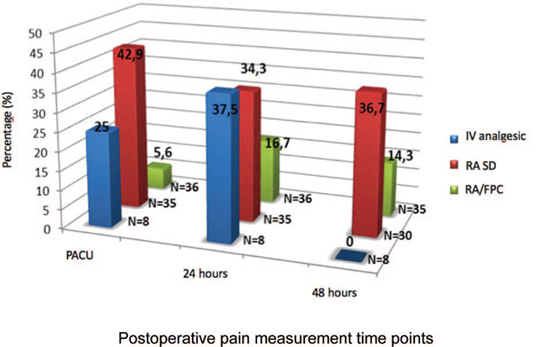

Seventy-nine PTKA were performed from September 2016 to June 2017 (Fig. 1). Table 1 illustrates the demographic and clinical characteristics of the population and the anesthesia and analgesia management during the trans operative period. The categorical pain evaluation at each measurement time point can be seen in Fig. 2. Figure 3 depicts the incidence of moderate to severe pain with the various multimodal analgesia techniques at the 3 time points measured. The incidence of compliance with the physical therapy goals 48 hours after surgery according to the various multimodal analgesia techniques is illustrated in Table 2.

Source: Authors.

Figure 1 Flow chart of patients undergoing TKR with the different general anesthesia and regional anesthesia techniques admitted to the study from September 2016 to June 2017.

Table 1 Demographic, clinical, and anesthesia and analgesia management characteristics of patients undergoing TKR

BMI=body mass index, SSRIs=selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors, FNB=femoral nerve block, FPC=femoral perineural catheter, IOP=intraoperative, NSAIDs=nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs.

* Value expressed as a mean (IQR).

Source: Authors.

Source: Authors.

Figure 3 Incidence of moderate to severe postoperative pain according to the different multimodal analgesia techniques measured at different time points.

Table 2 Incidence of compliance with physical therapy goals 48hours after surgery, according to the various multimodal analgesia techniques

PhT=physical therapy, IV=intravenous, RA=regional anesthesia, SD=single dose, FPC=femoral perineural catheter.

Source: Authors.

In terms of the known risk factors associated with higher postoperative pain severity 48 hours after surgery, 68.7% of the patients reporting moderate to severe pain were over 65 years old and had a history of a cardiovascu lar event; 62.5% presented a body mass index (BMI) >30, and in 62.5% remifentanil was used for managing anesthesia.

RA was used in most patients, and in nerve block, single-dose and continuous perineural infusion were characterized. On the basis of the homogeneity of the population, the similarity in the number of patients with each technique and the marked difference in the incidence of moderate to severe pain in the immediate postop and after 24hours, x2 and Fisher analytical tests were conducted in order to determine the relationship between each technique and the severity of pain, notwithstanding the fact that this is an observational study. A statistically significant relationship (P < 0.05) was found between the percentage of patients with mild pain in the PACU and the use of mutimodal analgesia techniques with continuous perineural infusion. The same is true for the percentage of patients with moderate to severe pain and the use of single-dose RA in the PACU. This relationship was not maintained after 24hours. The same analysis was used to assess the relationship between meeting 50% and 70% of the physical rehabilita tion goals according to the multimodal analgesia tech nique used, but no statistically significant (P > 0.05) relationship was identified.

Discussion

The characteristics of the population herein analyzed are mostly consistent with other populations reported in recent reviews, 27 evidencing a high prevalence of comorbidities and factors associated with difficult postoperative pain management. Multimodal analgesia includes several drugs associated with RA and was used in most of the cases. In a similar proportion, single-dose regional analgesia procedures and continuous infusion using a perineural continuous infusion catheter were conducted. The latter was more effective in preventing moderate to severe pain in the postoperative period over the first 48 hours of observation, although this difference declined with time, as illustrated in Fig. 3, probably because of the intervention of the multidisciplinary team during the intrahospital management. Furthermore, over 50% of the patients met at least 50% of the rehabilitation goals, regardless of the analgesia technique used.

These results show the broad heterogeneity in the management of anesthesia and analgesia in the everyday practice of a reference institution. This fact may be representative of real life in general, at similar institutions in the country. Furthermore, this is a motivation to continue to seek the standardization of anesthetic techniques for this type of specific procedures, and for training purposes of the anesthesiology staff in advanced regional analgesia techniques such as perineural cathe ters, or the establishment of alternate techniques whenever regional analgesia is not feasible due to logistics or to intrinsic patient-related factors. The systematic imple mentation of potentially more effective regimes for managing postoperative pain and with a stronger possi bility to meet the postoperative rehabilitation objectives is a pressing need.

There are unrecognized factors not managed before surgery that may contribute to the heterogeneity of the response to analgesia in these patients. Although the absence of response to conservative management for 6 months is an indication for surgery, the level of compliance with the various treatment guidelines estab lished by the scientific societies28 for managing osteoar thritis is unknown. This is evidenced by the lack of data on pharmacological therapy in the medical records of these patients. Adequate pain management before surgery could decrease the odds of developing central sensitization leading to an overexpression of symptoms during the perioperative period. Central sensitization together with the disruption of the descending control systems due to the presence of chronic pain have been identified as potential causes of hyperalgesia present in the tissues surrounding the knee joint. This is evidenced when doing tests that show less pressure and temperature tolerance in patients with severe osteoarthritic pain, in contrast to healthy controls and with osteoarthritis without severe pain. 29 Hyperalgesia has further been associated with prior opioid use, even if at low doses, in patients with chronic osteoarticular disease who are managed surgically. 30

Regional anesthesia is recognized as an useful analgesic strategy by multidisciplinary teams such as PROSPECT (Procedure Specific Postoperative Pain Management), a group that according to a systematic literature review makes recommendations based on the available evidence for each analgesic strategy in different surgical procedures. 31 It is striking however that although the last database review was conducted not long ago, dated November 2015, the level of evidence was not enough to recommend the use of combined RA techniques such as femoral nerve block (FNB) together with sciatic nerve block (SNB) and/or obturator nerve block (ONB), as well as alternate techniques such as intra-articular analgesia or TENS (transcutaneuous electrical nerve stimulation) in PTKA. 32

Notwithstanding the fact that SNB is one of the most popular RA techniques used in this study (85%), according to the most recent systematic reviews conducted in 201133 and in 2016, 20 its use in combination with FNB at a single dose or continuous perineural infusion does not seem to offer any clinically relevant advantages after the first 12 hours post-surgery, as compared with the isolated use of FNB. The concern about the limitation to conduct rehabilitation maneuvers, the risk of sciatic nerve damage as an intrinsic surgical complication, and the negative impact in terms of time, costs, and follow-up of these patients has generated a big debate on the systematic use of this nerve block. 34

The anatomical studies recently conducted evidence the complexity of the sensitive innervation of the knee, 35,36 and have been the basis for the development of new approaches to RA procedures. One of these approaches is the adductor canal block (ACB), whereby selectively blocking the vastus medialis nerve and the saphenous nerve37 results in similar effectiveness to the FNB for management of analgesia in patients undergoing total knee replacement. Moreover, the ACB preserves the quadriceps strength for the first 24 hours and facilitates ambulation, shortening the time to the Time Up and Go (TUG) test, although it is only significant at 6 hours in patients over 68 years of age. 38 Similar to this study, pain in movement during physical therapy at 48 hours was moderate to severe in a higher proportion of patients.

No relationship was found between the analgesic technique used and accomplishing 50% or 70% of the physical rehabilitation goals. So, it could be inferred that the analgesic technique is not the only factor responsible for this result, as evidenced by a recent meta-analysis showing no difference in the quadriceps strength using FNB or ACD in PTKA, 39 although the results are quite heterogeneous.

This study evidences that the RA such as continued femoral perineural infusion associated with single-dose SNB are more effective in controlling acute pain and are associated with a statistically significant higher proportion of patients presenting mild pain in the PACU. The single-dose block techniques are different in the sense that there is a higher proportion of patients with moderate to severe pain in the PACU. Most likely, the anesthesiologist's expertise in the regular use of perineural catheters plays a key role in the success of this advanced RA technique40 for pain control in the postop as they require higher skills and dexterity.

Despite the little evidence supporting the use of some pure and/or combined RA techniques vs other analgesic schemes, a recently published network meta-analysis showed that those approaches most frequently evaluated in controlled clinical trials (randomized controlled trials, RCTs) include FNB (as single-dose or continuous infusion), epidural analgesia, periarticular infiltration, and the combination of FNB and SNB, compared against the administration of opioids using the PCA system (pa tient-controlled analgesia).41 The best effectiveness profile in terms of rest pain, movement, use of opioids, and knee range of movement over the first 72 postop hours is achieved with combined RA techniques. Periarticular infiltration is less effective for rest pain than RA but are better than epidural analgesia or intrathecal morphine.

Likewise, periarticular infiltration performs better than liposomal bupivacaine, though with a less impact on the use of opioids and range of movement.

Periarticular infiltration may be effective when associ ated with a well-structured multimodal analgesia management regime, according to the needs of the patient, as shown in a recent clinical controlled trial (RCT) 42 wherein PTKA patients were randomized into 3 arms, comparing continuous femoral RA and single-dose SNB against ropivacaine periarticular infiltration, and liposomal bupi-vacaine periarticular infiltration. No significant differences were found in maximum pain levels 24 hours after surgery (rated as a 2-point difference in the numerical pain scale between the intervened groups at the time they were measured). However, there was a difference only in the PACU, with continuous FNB and single-dose SNV being the most effective technique to achieve mild pain. No significant difference was found either 24 and 48 hours after surgery (rated as 20 mg of morphine oral equivalent difference between the treated groups at the time of measurement).

As this is an observational study, the results may be significantly impacted by chance and the absence of a statistically denied sample calculation that could strengthen the validity of the study. The results of the analytical tests used as indicator of random association between the analgesic techniques and the outcomes shall be carefully interpreted, as the design of the study was not experimental and gives rise to a potential type II error. This study shows how at a referral institution multimodal analgesia, including RA procedures, is widely used with a variable efficacy and an incidence of moderate to severe postoperative pain that can be improved in the future. An experimental design will be suggested in order to validate the conclusions of this study.

Ethical disclosures

Protection of human and animal subjects. The authors declare that the procedures followed were in accordance with the regulations of the relevant clinical research ethics commit-tee and with those of the Code of Ethics of the World Medical Association (Declaration of Helsinki).

Confidentiality of data. The authors declare that they have followed the protocols of their work center on the publication of patient data.

Right to privacy and informed consent. The authors declare that no patient data appear in this article.

texto em

texto em