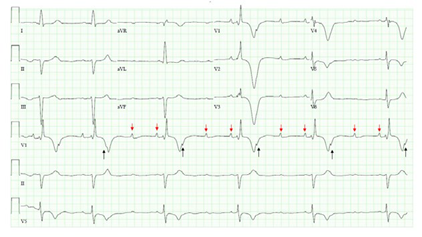

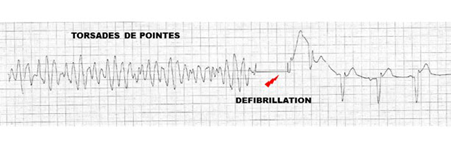

Systemic sclerosis is an immunological disorder characterized by tissue fibrosis and multi-organ dysfunction.1 The accompanying images exhibit electrocardiographic changes in severe systemic sclerosis. Advanced 3:1 atrioventricular block, best observed in Lead Vi, suggests extensive fibrosis of the conduction system (Image A). While one P wave is buried in the T wave (black arrows), two are evident (red arrows) along the isoelectric line. Bradyarrhythmia related prolonged QT interval, best measured in Lead II represents increased risk for torsades-de-pointes, a polymorphic ventricular tachyarrhythmia. Additionally, right bundle branch block with giant T wave inversions (T wave depth > 10 mm) in precordial leads V2- 4 suggests pulmonary hypertension. Post-induction the rhythm abruptly changes to torsades-de-pointes (Image B) necessitating defibrillation.

SOURCE: Authors.

IMAGE A Advanced 3:1 atrioventricular block, best observed in Lead Vi, suggests extensive fibrosis of the conduction system.

SOURCE: Authors.

IMAGE B Post-induction the rhythm abruptly changes to torsades-de-pointes necessitating defibrillation.

Immune deregulation and recurrent ischemia-reperfusion injury in systemic sclerosis leads to vascular dysfunction, myocardial systolic and diastolic impairment and conduction system fibrosis. Consequently, pulmonary arterial hypertension, heart failure, coronary artery disease and arrhythmias occur frequently in severe disease. Patients often present with dyspnea, fatigue and syncope.

Advanced atrioventricular blocks merit expert consultation to assess need for transvenous pacing, as unexpected progression to complete heart block and/or torsades-de-pointes increases risk of sudden cardiac death.2 Pulmonary hypertension in systemic sclerosis increases right ventricular strain and elevates end-diastolic pressure with leftward interventricular septal shift, compromising left heart filling and ejection. Decreased cardiac output and anesthesia induced hypotension jeopardize coronary perfusion and perpetuate right ventricular ischemia. In addition to causing ventricular tachyarrhythmias, myocardial ischemia can worsen atrioventricular conduction, leading to complete heart block.

Consequently, pre-induction establishment of invasive arterial monitoring and transvenous pacing is prudent. Anesthetic goals include decreasing pulmonary vascular resistance with pulmonary vasodilators like epoprostenol and maintaining systemic vascular resistance with vasopressors like norepinephrine to ensure adequate coronary perfusion. Although hemodynamically stable torsades-de-pointes frequently suppresses with magnesium administration and overdrive pacing, pulseless ventricular tachyarrhythmia necessitates defibrillation.3

texto en

texto en