INTRODUCTION

In our setting, orotracheal intubation is usually performed in emergency situations where people act first and ask later, hence the relative frequency with which intubation occurs in palliative care patients. Withdrawal of life support after it has been instituted can be a complex decision. Physicians usually express emotional anxiety at the prospect of making the decision and having to participate in life support withdrawal. The indication for palliative extubation is strongly grounded on ethics, underpinned by the ethical principles of proportionality, justice and autonomy, when death is inevitable or recovery to an acceptable quality of life is not possible. The development and implementation of a standardized protocol for palliative extubation is useful and makes ethical decision-making easier.

VITAL AND FUNCTIONAL PROGNOSIS

The first obstacle physicians find in the face of a critically ill patient is to arrive at an objective and reliable vital and functional prognosis. Patients admitted to the intensive care unit (ICU) may have, aside for serious illnesses, other comorbidities and multiple organ dysfunction. In such cases, the severity of the disease process is not related as much to the etiology as to the individual's own physiological response mechanisms 1.

The decision to perform palliative extubation requires adequate selection of patients with a short-term unacceptable vital prognosis (Charlson Comorbidity Index less than 50%) or very compromised global functionality (ECOG 4, Barthel < 35). On the Karnofsky scale, a score of less than 50 indicates a high risk of death within the next six months in oncology patients, while the PALIAR index (>7.5 very high risk) estimates six-month prognosis in patients with non-oncologic advanced chronic disease 1.

Prognostic uncertainty is a pervasive problem in medicine. Some retrospective reviews mention survival rates as high as 11% after palliative extubation, but this should not be a limitation for decision-making and does not justify choosing never to remove life support, because such a decision entails its own ethical considerations 2.

End-of-life communication techniques

Palliative extubation of the alert patient implies unique psychosocial and ethical considerations. Assessment of the degree of understanding and the ability to take part in end-of-life decisions can be accomplished even by means of non-verbal communication, although the vast majority of patients cannot be involved in the decision.

Communication techniques in relation to end-of-life care are useful. The modern concept of human dignity is based on the idea that all human beings have the innate right to freedom, which is the source of dignity. Even when the person loses the ability to make decisions, the right for his or her will to be respected remains and, therefore, encouraging advanced directives frees families from the need to make difficult decisions and helps honor the patient's autonomy.

When advance directives are lacking, the family should be urged to understand the patient and sympathize with previously expressed wishes or understand the value system against which he or she made decisions in the past. This will lead to decisions that ultimately are respectful of autonomy and dignity 1(Table 1).

TABLE 1 Useful phrases to guide decision-making while respecting the patient's wishes.

SOURCE: Adapted from McVeigh et al. 4.

Families of critically ill patients value communication as one of the most important facets of care. Quality of communication relates not only to the information provided, but also to closeness, empathy, psychosocial and spiritual support, recognition of emotions, and a listening attitude from the medical team.

Even if the approach is appropriate, the family may still reject palliative extubation. In no case can the decision be made unilaterally, and it is important to garner the support of an interdisciplinary team. However, palliative care is non-existent or there is a very limited offering in most areas 3. Psychological support is recommended during the bereavement process, and communication should remain open, inviting the family to always think what the patient would say if he or she could make the decision.

ETHICAL AND LEGAL CONSIDERATIONS

The next obstacle that the physician is required to overcome has to do with the legal and ethical biases surrounding life support. The act of withdrawing or maintaining a treatment is seen as one and the same from the ethical perspective, and these practices are morally permissible in accordance with the principles of autonomy, beneficence and non-maleficence 4. The physician is under no obligation to provide or maintain futile treatments, understood as those treatments that do not accomplish the expected objective. In this regard, maintaining those treatments is considered clinical malpractice because they go against human dignity while consuming health resources in vain, which is contrary to the principle of distributive justice 5.

Every patient is free to reject any form of treatment, even though such a decision might result in death. This right to autonomy can be exerted both verbally as well as in writing. The decision must be discussed collectively, involving the family, and by consensus. Sometimes, in view of reasonable doubt, it is advisable to continue with intensive treatment subject to very specific therapeutic objectives, during a reasonable time period.

REORIENTATION TOWARDS NEW THERAPEUTIC OBJECTIVES

Having overcome the different obstacles, the palliative extubation procedure must be performed by a multidisciplinary team with the main objective of avoiding patient suffering until the time of death.

Although death after removing mechanical ventilation usually occurs within less than 24 hours, 10% of patients survive longer than 24 hours; and in patients with neurological conditions, the time period may be unpredictable and last days or even weeks 2.

Symptoms requiring preventive interventions may manifest following extubation. These include respiratory failure, dyspnea, delirium, agitation, pain, psychological anxiety and difficulty clearing secretions. No medication will provide relief from pain or suffering instantly, hence the need to not wait until the onset of signs of distress to provide excellent analgesia and sedation.

It is reassuring for the family to understand the preventive use of medications and assessment for non-verbal signs of discomfort such as grimacing, body tension and respiratory work in order to guide drug doses. It is also important to prepare families for the typical breathing patterns associated with the dying process, such as pauses, panting, involuntary jaw movements and stridor, and help them understand that they do not indicate suffering.

Palliative sedation

Palliative sedation consists of maintaining the unconscious state in a patient with a terminal disease in order to alleviate refractory physical or psychological anxiety. Assurance that the patient will not experience symptoms during life support withdrawal can only be given if the patient is under sedation during the procedure.

The doctrine of double effect and the principles of proportionality and autonomy play a key role in the practice of palliative sedation. The doctrine of double effect assesses the intent of a treatment that has a double effect - sedation and respiratory depression - without surrendering to the wish of accelerating death, which can be demonstrated by doing everything possible to avoid the undesired effect. In this case, this is done by assessing the symptoms and maintaining proportionality between the therapeutic objective and the infusion dose.

The notion that drugs used for sedation can accelerate death is an issue and may limit the provision of appropriate doses. There is no evidence that higher opioid doses used at the time of terminal extubation actually accelerate death; the opposite has been shown in studies in which high doses of opioids were associated with a short but significant increase in time until death 6.

In practice, opioids are used in combination with benzodiazepines, titrated up to sedation levels. This allows the use of opioid doses below the range of respiratory depression, which occurs with doses equal to or higher than those that cause sedation. This practice allows death to set in at the pace determined by the disease.

PALLIATIVE EXTUBATION PROTOCOL

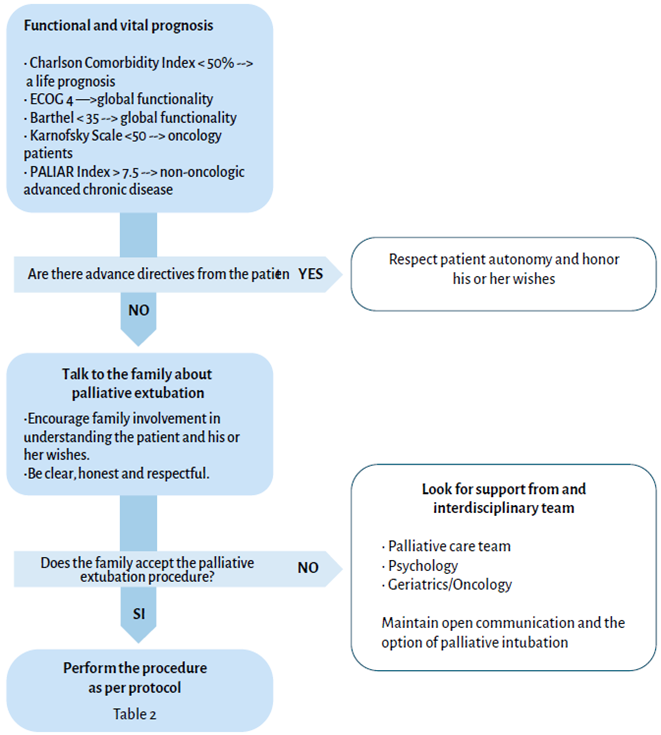

Figure 1 shows a flow diagram to guide decisions based on clinical scores, taking into account the principle of autonomy, thus allowing the clinician to work around the challenges of palliative extubation.

Developing and implementing a protocol to guide life support withdrawal is useful and makes ethical decision-making easier for nurses and physicians alike. Table 2 shows recommendations based on clinical practice guidelines to carry out the palliative extubation procedure 7,8.

TABLE 2 Palliative extubation protocol.

SOURCE: Adapted from McVeigh et al. 4.

CONCLUSIONS

Although prognostic scales have not been useful for predicting survival or making end-of-life decisions, terminal extubation is an option that needs to be considered when death is inevitable or recovery to an acceptable quality of life is not possible.

Human dignity is based on the idea that every human being has an innate right to freedom, and it is our duty to guide the family in honoring the patient's autonomy. Maintaining futile treatments is considered clinical malpractice because they are contrary to human dignity. In contrast, palliative extubation is ethically permissible, underpinned by the principles of autonomy, beneficence and non-malificence. Once the various obstacles have been overcome, palliative extubation must be performed by a multidisciplinary team, bearing in mind the main objective of avoiding patient suffering at all cost during the entire process of dying. Having a standardized protocol for life support withdrawal makes ethical decision-making easier.

ETHICAL RESPONSIBILITIES

The authors declare that this paper is a non-systematic topic review and reflection and, therefore, no human or animal research or experiments were conducted.

No patient data appear in the article and there was no need to obtain informed consents from any potential participants.

text in

text in