What is our knowledge on the topic?

The right to sign an Anticipated Directive Document (ADD) was approved through Law 1733 of 2014 and enacted according to Resolution 1051 of 2016 and 2665 of 2018 in Colombia. The poor knowledge of healthcare professionals regarding the ADD has been suggested as the main cause for the lack of response by patients to submitting their Advanced Directives.

What new contributions does the study make?

This is a pioneer study that delves into the knowledge and experiences of healthcare providers with regards to the ADD in Colombia. The findings indicate that knowledge of the health practitioners about the ADD is poor, as well as their perception regarding the number of ADDs signed by patients. The results show the immediate need to educate all healthcare professionals on the conceptual, ethical and legal aspects of the ADD, and the non-deferrable nature of the institutional implementation of Programs in the area of Planning for Advanced Directives (PAD).

INTRODUCTION

Various changes have been introduced in modern medicine with regards to the roles and rights in medical practice, giving the patient a protagonist role in the doctor-patient relationship. Respect for the autonomy of the patient is one of the four biomedical principles that has overwhelmingly evolved in the past few years, with the support of public policies and the academia in the area of bioethics. This right becomes particularly relevant under clinical circumstances in which the patient is unable to make his/her own decisions. Legally, an individual may exercise his/her right to autonomy via the Informed Consent 1-4 or the Advanced Directives Document (ADD), when he or she is unable to express his/her will. 1,3 The foundation of the Advanced Directive (AD) is the ethical principle of Prospective Autonomy 5. The pillar of a dignified death process is the acknowledgement of self-determination of every human being. Each person has a particular interpretation of the meaning of dignified death. When someone is no longer able to make decisions, it becomes difficult to honor end-of-life wishes and preferences, which violates the idea of a dignified death. 6,7 The applicability of the ADD contributes to improved quality of care and is an effective approach to ensure respect for the rights of autonomy, self-determination and dignity of patients. Consequently, it is essential for healthcare practitioners to learn about the basic and practical aspects of the ADD.

The Colombian legislation approved the right to sign an ADD pursuant to Article 5 of Law 1733 of 2014 8, known as the Consuelo Devis Saavedra Law. Two years later, Resolution 1051 of 2016 9, established the requirements for drafting the manuscript which simply states that the ADD should be certified by a Notary. Subsequently, Resolution 2665 of 2018 10, expanded the scope of the Law: allows minors between 14 and 18 year old to sign a ADD; allows for an AD to be video or audio-recorded, and use other media; and provides other options to formally submit the AD, such as signing the document with two witnesses or before the treating physician. According to these regulations, one could expect that these new avenues to formally submit the ADD shall increase the number of signatories. However, there is no evidence on this matter at the national level.

The literature says that the limitations for the implementation of the ADD may include: a). concerns of healthcare practitioners about when to address the discussion and which patients should plan their ADD; the result is that in many cases the issue has been raised too late. b). Who is the most suitable practitioner to initiate the AD process; and c). How will the ADD be entered in the electronic medical record for easy and prompt access when reviewing the patient's preferences in the future. Studies conducted in other countries about the attitudes and knowledge of practitioners about the ADD have shown that their attitudes are favorable but their knowledge is weak and probably insufficient. 11-15 In Colombia there are few studies assessing this variables.

Hence, the purpose of this study was to describe the knowledge and experience of healthcare professionals with regards to the right to sign the ADD, among the membership of six Colombian Scientific Societies and to enquire about barriers to the ADD implementation in daily clinical practice.

METHODS

Population

The study sample included medical practitioners registered in the database of the Colombian Association of Palliative Care, Association of Palliative Care of Colombia, Colombian Association of Gerontology and Geriatrics, Colombian League Against Cancer, Colombian Society of Anesthesiology and Resuscitation, and the Colombian Association of Critical Medicine and Intensive Care, as of January 31st, 2021. The investigators extended the corresponding invitations to the societies to participate in the study and each society forwarded the survey to the personal email of its members, based on the information in their databases; the surveys were sent twice, with a one-week interval. The inclusion criteria included the willingness of each member of the different societies to participate, answering all the questions in the survey, and each participant should answer the survey only once. The survey was administered in February 2021.

Content of the survey and variables

The e-survey with seventeen questions was designed by the investigators and included the informed consent and a short introduction about the purpose of the study (complementary material attached).

The survey was anonymous and developed by the investigators. The questionnaire was subject to approval in a pilot study. The variables were grouped into 5 sections: a) General: profession, work setting and experience; b) Knowledge about the ADD; c) Medical experiences with AD; d) Personal experiences with AD; and e) Potential limitations for its implementation in the clinical setting. The e-survey interface was designed by specialized Sociedad Colombiana de Anestesiología y Reanimación (S.C.A.R.E.) personnel, using the QuestionPro platform. The outline and the type of questions and answers were analyzed and discussed by the authors at least on three occasions, before sending out the questionnaire to the respondents via e-mail. The final consolidated information of the statistical data was electronically forwarded from S.C.A.R.E. to the authors for its corresponding analysis.

Ethical considerations

According to Article 11 of Resolution 8430 of 1993 of the Colombian Ministry of Health, this study is considered a minimum risk investigation since no intervention is involved. All of the participants submitted their informed consent in order to proceed with the anonymous completion of the survey. The final consolidated results were anonymous and only aggregate results are submitted, with no detailed information about the individual answers. The data collected were summarized and reported in aggregate and used for scientific purposes only.

Statistical Analysis

The sample used in the study was a convenience sample collected after sending the questionnaire to the various Societies of professionals involved with critical or palliative care patients. The sample size was not estimated since the total number of the population was unknown. The qualitative variables were described as proportions, while the quantitative variables were expressed as medians and interquartile ranges, based on their distribution. The correlation among the qualitative variables was assessed using Pearson's chi-square with a statistical level of significance of less than 0.05. The statistical analysis was based on the STATA v13 software.

RESULTS

General characteristics of the study population

A total of 11,715 invitations were sent to the personal e-mails of the membership: S.C.A.R.E.: 9.,442 invitations and other societies: 2.273 invitations. 536 replies were received, 180 from scientific societies, 395 from S.C.A.R.E. Of the 536 answers, 3 of the respondents refused to participate, therefore the analysis was based on 533 answers. The percentage of replies was 4.54 %.

Most of the respondents were head nurses (49.34 %), followed by physicians (44.09 %) of which 31.14 % were specialists and 12.95 % were subspecialists.

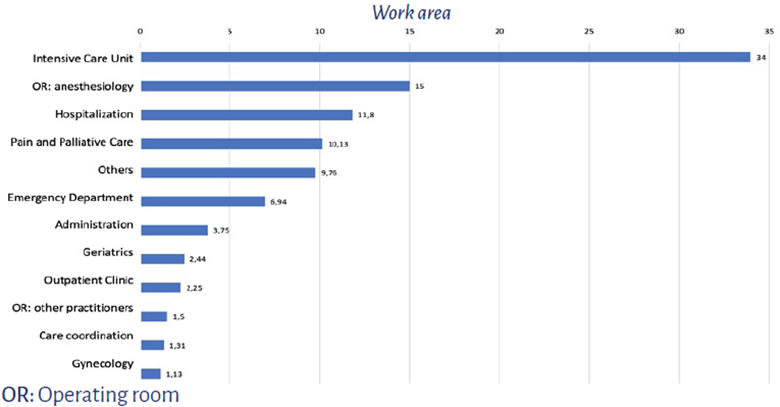

With regards to the work environment, 34 % worked in the intensive care unit, 15 % in the operating room and 10.13 % in pain and/or palliative care units. The "others" category included education, internal medicine, oncology, promotion and prevention, home care, wounds clinic, chronic patient care, perfusion, psychiatry, referral units, renal unit, mental health, public health, bio-ethics, hematology, diagnostic imaging, nutritional support, cardiology, and one student (Figure 1). The mean number of years of experience in the respective occupational areas of the participants was 9 years (IQR: min 4 - max 18).

Knowledge about the ADD

Overall, 54 % of the participants (n = 286) said they were not aware of the existence of a Law that governs the ADD in Colombia, while 34.33 % of the participants (n = 183) said they were familiar with the requirements of the document. A comparative analysis by population groups revealed that pain and palliative care specialists were more knowledgeable about the law and the mandatory requirements for the ADD (Tables 1 and 2).

TABLE 1 Knowledge of the different professionals regarding the Law governing the ADD.

| Work area | Are acquainted with the Law that governs the ADD in Colombia % (n) | |

|---|---|---|

| Yes | No | |

| Pain and palliative care | 77.3 (41) | 22.6 (12) |

| Intensive Care Unit | 45.8 (83) | 54.1 (98) |

| OR: anesthesiology | 31.2 (25) | 68.7 (55) |

| Others | 44.7 (98) | 55.2 (121) |

The is a statistical significant difference (Pearson's x2 = 28.0732; p < 0.05).

SOURCE: Authors.

TABLE 2 Awareness of the practitioners regarding the requirements to sign the ADD.

| Work area | Are acquainted with the requirements for signing an ADD in Colombia % (n) | |

|---|---|---|

| Yes | No | |

| Pain and palliative care | 66.04 (35) | 33.9 (18) |

| Intensive Care Unit | 34.2 (62) | 65.7 (119) |

| OR: anesthesiology | 23.7 (19) | 76.2 (61) |

| Others | 30.5 (67) | 69.4 (152) |

OR: Operating room. There is a statistically significant difference (Pearson's x2 = 28.9627; p < 0.05).

SOURCE: Authors.

Medical experiences regarding advanced Directives

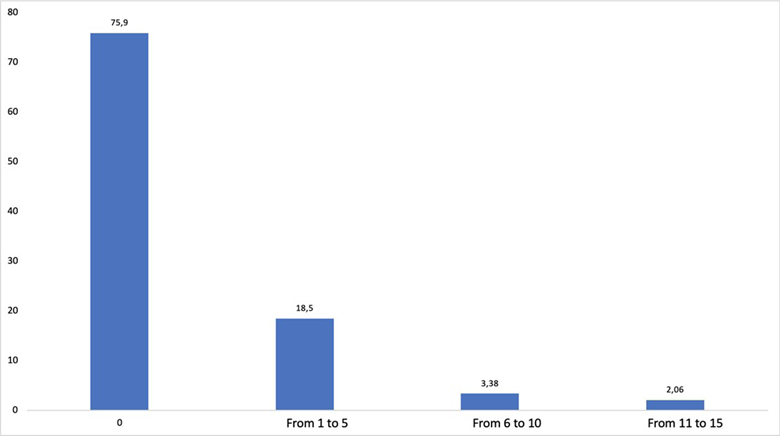

Over the course of the past year, 24 % of the practitioners received one or more ADD from their patients (Figure 2). Just 53 % of the practitioners inform and educate their patients about the ADD because they believe they should sign the document, but they don't have it.

SOURCE: Authors.

FIGURE 2 Number of patients who submitted an ADD to the practitioner over the last year.

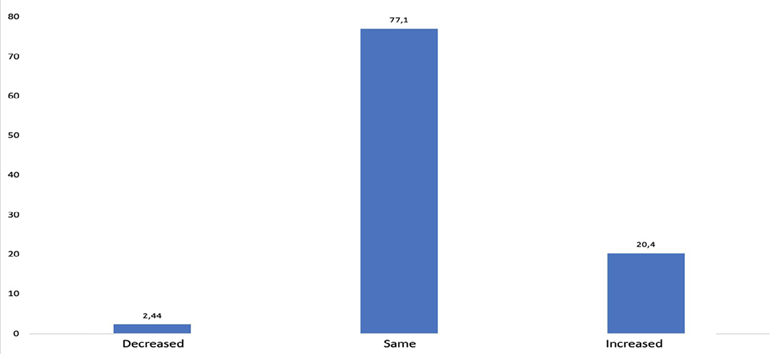

77.1 % of the practitioners surveyed perceived the same frequency of patients completing an ADD after the Resolution was passed in 2018 (Figure 3).

SOURCE: Authors.

FIGURE 3 Practitioners' perception about the number of ADDs after the adoption of the Resolution in 2018.

86.6 % of healthcare practitioners say they honor an ADD, even if the patient may benefit otherwise (Table 3).

TABLE 3 Willingness of practitioners to honor the ADD.

| Work area | Willingness to honor the ADD % (n) | |

|---|---|---|

| No | Yes | |

| Others | 15.98 (35) | 84.02 (184) |

| Pain and Palliative Care | 9.43 (5) | 90.57 (48) |

| Intensive care unit | 11.05 (20) | 88.95 (161) |

| OR: anesthesiology | 13.75 (11) | 86.25 (69) |

OR: Operating room. The is no statistically significant difference (Pearson's x2 = 2.633; p = 0.452).

SOURCE: Authors.

Personal experiences with regards to advanced directives

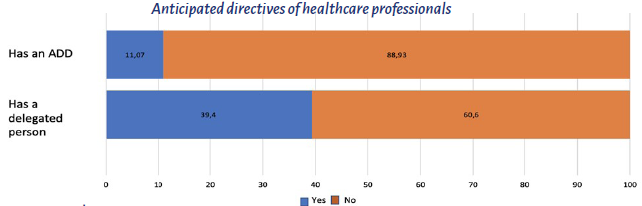

In terms of the applicability of the ADD in the personal life of the healthcare professional, only 11.07% said they had completed their ADD and 39.4% said they had a proxy and informed their families in case they faced a clinical situation in which they were unable to make a decision (Figure 4).

Possible limitations to the use of ADD

89.6 % (n = 478) of the said that even if the patient does not ask, the best timing to inform the patient about the ADD is during the initial contact of any healthy patient or a patient diagnosed with an end-stage, chronic, degenerative or irreversible disease. The participants were offered the opportunity to elaborate and they said: "The patient has the right to be informed about the ADD", "The physician is required to educate the patient", "patients do not read the laws", "patients do not ask because of lack of information and lack of awareness about the laws".

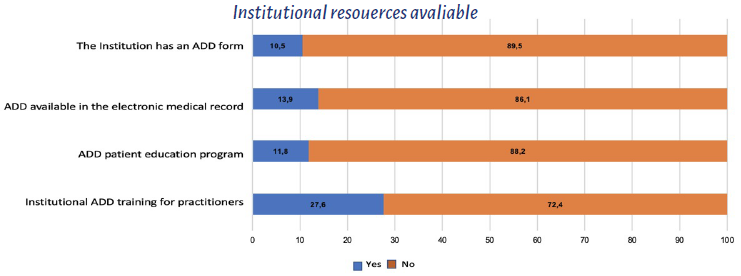

97 % of the patients agreed that the healthcare professional in charge of informing and educating the patient about the ADD is the physician, regardless of whether he/she is a GP, a specialist or a subspecialist. 72.4 % of the participants do not receive any professional training about the ADD in their institution, and 88.2 % say that there no ADD educational programs for their patients in their institution. 86.1 % said that the electronic medical record in their healthcare institutions does not have access to an ADD and 89.5 % said that there is no predesigned ADD form (Figure 5).

DISCUSSION

The study delved into the knowledge and experiences of healthcare personnel in several clinical services providing care to chronic, critical or palliative care patients who could benefit from an ADD in Colombia. The analysis showed poor knowledge about the ADD among healthcare practitioners. Specifically, just 34.33 % of the patients confirmed being aware of the ADD requirements, while over one half of them said they didn't know there was a Law and requirements for signing an ADD. Similar results were reported by Aguilar et al. 12 in 2018, with only 22.2 % of the practitioners stating that they had read the ADD law; notwithstanding the fact that the law was enacted in Spain over 16 year ago, the level of awareness is considered to be low 12,15-17. It should be highlighted that those who are more knowledgeable about the law and requirements for signing the ADD according to our study are pain and palliative care specialists. Similar studies agree on the perception of a higher level of awareness about the ADD among the professionals who had themselves an ADD, had palliative care training, those who were asked to provide information by their patients, and those who had read and were familiar with the ADD law. 11,12

The overall perception of the healthcare professionals regarding the number of ADDs prepared by patients is the same after the enactment of the Law in Colombia. This observation is in contrast with the results obtained regarding the poor knowledge of the requirements to sign the ADD and the low number of ADDs prepared but practitioners themselves, in addition to the low numbers of ADDs prepared by patients. However, the number of professionals who said they had an ADD (11.7 %) in this survey is higher than the al 3 % reported in other studies 12. The number of elderly patients that have submitted an ADD is low; however, they show a positive attitude towards the document 11,17-19. A study conducted in Colombia in end-of-life patients 20, found that 14 % had signed their own advanced directive. In this second study, a higher number was reported since 24 % of the practitioners said they had received one of more ADDs over the last year. Carrillo and Gómez 21 conducted a study in a home for the elderly in Cartagena, and concluded that there is a lack of knowledge about the ADD by this group of people and that there is a need to educate the staff involved with the care of geriatric patients 21. The lack of education of practitioners with regards to the ADD has been suggested as the primary cause to account for the poor response of patients to submitting ADDs. 11,15-17

This study found that healthcare professionals have a positive attitude and respect the ADD, supported by 86.6 % of the participants. Likewise, Nebot et al. 19 found that 97.6 % of the practitioners say they are aware of the right of people to fulfill and respect the ADD 19. Patients are more willing to converse about end-of-life care when the topic is approached in the office, and the discussion is more satisfactory when there is a trust-based doctor-patient relationship. 18 It has been shown that up to 85.6 % of the elderly agree that the doctor is the right person to start the conversation about the ADD 18, similar to the results obtained in this study, where 97 % of the professionals say that it should be the doctor, regardless of whether he/she is a specialist, a non-specialist, a rural doctor, a GP or a subspecialist. The world expert consensus guidelines suggest that healthcare practitioners should initiate patient education by using information material and repeated conversations during the clinical visits, as the most effective strategy to increase the number of ADDs signed. 12

Every healthcare practitioner should be knowledgeable about the scope of the law in terms of their involvement as part of their professional practice. 22 Regardless of their profession or academic level, all the healthcare staff members shall be required to inform and educate patients with regards to their rights 22,23, including the recent right of signing an ADD. Any person can experience an acute clinical situation that makes it impossible for him/her to exercise the right to self-determination. 24 This right does not discriminate between being healthy or ill; the physician should inform and educate all patients, at all times, about the ADD. During the education process, patients should be made aware that the AD may be revoked or amended at any time, in addition to assuring them that neither the family or the practitioner are entitled to change the AD. 24 It is also important for the patient to clearly understand that he/she decides whether to render an AD or not, and when to do it.

In Colombia, Calvache et al. 25 argues that physicians were unaware of whether the patient had an AD in 65 % of the cases and concludes that doctor-patient and/ or family communications strategies are urgently needed. 25 Previous studies 11,19 conclude that most of the professionals do not ask or check whether a critically ill patient has submitted an AD; the habit of asking about the ADD drives respect for the right to autonomy, self-determination and dignity by the family and the healthcare practitioners themselves. 19 Bolívar and Gómez 24 identified the following obstacles in implementing the ADD in Colombia: lack of education of the healthcare professionals, poor awareness of the right to sign an AD among the general population, and the lack of a national registry available for consultation by practitioners. 24 These are all aspects to assess and consider when designing public policies addressed to reinforce this right.

As of this date, these obstacles have not improved. The study identified a high percentage of answers urging a prompt intervention with regards to the lack of institutional training of healthcare professionals (72.4 %), the lack of patient education programs (88.2 %), the non-availability of the ADD in the electronic medical record (86.1%), and the absence of institutional ADD forms to facilitate the process to both patients and doctors (89.5 %). Yllera 11 identified that 90 % of the practitioners had no training in the ADD and expressed the need to educate and inform about the value of ADDs and the procedure to submit the document, not only practitioners but also patients. 11,15-19 Similarly, the author recommends disseminating the information in the primary care and emergency departments, since there is often limited access of patients to specialized care. 11

The best ADD form is simple and easy to identify the objectives and specific patient preferences in clinical emergency settings, in addition to giving the opportunity to express the patient's values and end-of-life preferences. 26 Healthcare institutions should develop a section in the electronic medical record so that the practitioner may be able to expeditiously record, consult, review and replace the ADD at any time. 26 A randomized clinical trial 27 found that the group who participated in the Advanced Directives Planning Program were significantly more sympathetic in the selection of palliative care and the submission of the ADD by the patients (p < 0.001) 27.

Although the sample size in this study was not significant, there was a larger number of participants as compared to the numbers described in the literature. One could speculate that the reason for the low level of participation was fatigue and lack of time due to the COVID-19 pandemic, or not being used to participate in electronic academic surveys, which are a valuable modern tool for the advancement of knowledge. The limitations of this study include the inadequacy of the assessment instrument used to collect information from the participants. Some of the questions asked regarding experiences, have a significant social desirability and this may affect the results. Similarly, these questions have an intentionality or practice undertone, which could have been a confounding bias with regards to the mindset about ADs, the key research variable in this study.

One may then conclude that the overall perception of healthcare professionals regarding the number of ADDs signed by patients is still the same after the enactment of the Colombian Law; the knowledge of the practitioners on the matter is poor and currently there are still barriers to the implementation of the ADD.

It is imperative to educate healthcare professionals in the conceptual, clinical, ethical and legal aspects of the ADD, and to promptly implement programs on Planning of Advanced Directives at the institutional level. We suggest that future studies compare the results after implementing training programs for healthcare professionals.

ETHICAL RESPONSIBILITIES

Ethics Committee Endorsement

This study was approved pursuant to Minutes CEI-2021-02001 of January 29, 2021 of the Research Ethics Committee (CEI) of Fundación Cardiovascular de Colombia in Bucaramanga. Subsequently, the project was approved by the Research and Scientific Publications Area of the Sociedad Colombiana de Anestesiología y Reanimación (S.C.A.R.E.)

Protection of persons and animals

The authors declare that no experiments in human beings or animals were conducted for this research. The authors hereby affirm that the procedures used were consistent with the ethical standards of the responsible human experimentation committee and pursuant with the World Medical Association and the Declaration of Helsinki.

Confidentiality of the data

Each of the participating medical Societies followed the confidentiality rules for the management of data pursuant to their bylaws. The final consolidated data was anonymous.

The authors declare that they have followed the protocols of their respective institutions on the publication of patient data.

text in

text in